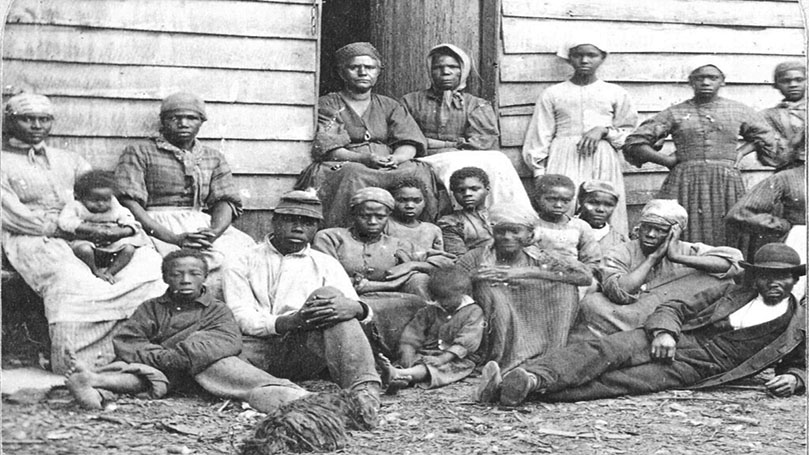

The year 2019 marked the 400th anniversary of the beginnings of slavery in North America. Chattel slavery, related directly to the development of merchant or commercial capitalism and the early history of industrial capitalism, would last for 249 years and end in 1865 with the collapse of the Confederate government, the surrender of the Confederate armies, and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

That was by no means the end. The Civil War, as the progressive historian Charles Beard1 contended, was a “second American Revolution,” which transformed and greatly expanded the powers of the federal government and saw the development of land distribution, state-supported infrastructure, and educational development, as well as international trade policies which fostered rapid industrialization and the creation of both large industrial corporations allied to large investment banks (monopoly capitalism) and an urban industrial working class.

While Beard, an economic determinist, was no Marxist, Karl Marx had more than 60 years earlier analyzed the Civil War as one that had to became revolutionary to abolish slavery, even if it was consciously fought to preserve a constitutional union which could no longer be preserved in its old form.

The New York Times last year launched the 1619 Project to study the effects of slavery as an institution through all of U.S. history. Given the upsurge of racism in all of its expressions—color racism against African Americans and all people considered “non-white”; “Yellow Peril” racism against East Asians; anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim racism, aka anti-Semitism and Islamophobia; and attacks on recent non-European immigrants—this was and is a necessary project.

The Times editors, realizing perhaps the dangers posed by the Trump administration to all civil rights and civil liberties, turned to younger African American scholars who study the history of slavery in relationship to both the history of capitalism and the influence of racism in U.S. history from the first colonial settlements to the present Trump administration.

The series has sought to reach social studies curricula in school districts throughout the country, producing a backlash by organized conservative groups who have long seen themselves as the policemen of America’s past.

What, so far, have these articles been about?

They range from “American Capitalism Is Brutal: You Can Trace That to the Plantation” by Matthew Desmond to “How Segregation Caused Your Traffic Jam” by Kevin Kruse; “How False Beliefs in Physical Racial Difference Still Live in Medicine Today,” an essay by Linda Villarosa; “Why American Prisons Owe Their Cruelty to Slavery” by Bryan Stevenson”; “Why America Does Not Have Universal Health Care? One Word: Race” by Jeneen Interlandi”; “What the Reactionary Politics of 2019 Owe to the Politics of Slavery,” an essay by Jamelle Bouie; and “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America” by Khalil Gibran Muhammad.

The Right-Wing Critics of the 1619 Project

Most of this reflects work that draws upon a half century of scholarship made possible by the Civil Rights movement—scholarship that right-wing conservatives in the tradition of the old House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) see as an integral part of a “culture war” launched by multi-culturalists, Marxists, and radical feminists to “brainwash” youth and “subvert the American way.”

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that attacks have come from the National Review, which has served as the leading journal of conservative opinion since the early 1950s, and the Federalist, a publication of the Federalist Society, the major organization of conservative attorneys and jurists. The latter has served as a kind of employment agency for the Justice Department and the federal judiciary in the Reagan, Bush, and Trump administrations, undermining workers’ rights, civil rights, and civil liberties won by the American people since the Great Depression.

These attacks echo the policies of right-wing Republican governors and legislatures to effectively ban textbooks which say “the wrong things” on labor, civil rights, and civil liberties questions. Howard Zinn’s classic, A People’s History of the United States, is perhaps the best-known case: written as a broad and honest narrative that people can understand and use to compare with what they have been taught, it has long been a focus of these attempts at formal censorship.

The Liberal Critics of the 1619 Project

Another source of the backlash has been a “protest” letter from five historians, which has brought the 1619 Project to the attention of a larger audience. Not associated with the likes of the Heritage Foundation or a Koch brothers–created group, four of these scholars are considered liberal. Well regarded in their fields, the letter’s co-signers include Victoria Bynam, professor emeritus from Texas State University, who has written about poor white opposition to the slaveholders in the antebellum South and of gender repression and social control in the post–Civil War South. The latter is an expression of the new historical scholarship made possible by the Civil Rights movement that has influenced many fields—the scholarship that the 1619 Project continues and Bynam now protests. James Oakes of the City University of New York has written distinguished works on the Republican Party as an anti-slavery party and the relationship of Frederick Douglass to Abraham Lincoln. James McPherson is a distinguished historian of the Civil War who has won major awards and who has appeared in many documentaries on the Civil War and Reconstruction. Gordon Wood, professor emeritus from Brown, is a leading historian of the American Revolution. I also respect and have fond memories of Wood, who taught at the University of Michigan when I was a graduate student there.

The letter’s author, Sean Wilentz of Princeton University, however, is different from the co-signers. Writing histories that won awards celebrating the republicanism and “democracy” of Jefferson and Jackson for and by working people, Wilentz became a friend of Bill and Hillary Clinton, and an advocate and defender of the Clinton administration.

Writing often in newspapers and news magazines, in 2008 he tried to act as an attack dog for the Clinton campaign against Barack Obama. First in the New Republic, he charged Obama with creating “manipulative illusion[s]” and “distortions,” and having “purposefully polluted the [primary electoral] contest” with “the most outrageous deployment of racial politics since the Willie Horton ad campaign in 1988.” Although he was sharply criticized for this comparison of the Obama campaign with what was the most openly racist appeal in a presidential election by a major party candidate in modern American history, he responded by attacking his critics. During the Democratic National Convention, Wilentz charged in Newsweek that “liberal intellectuals have largely abdicated their responsibility to provide unblinking and rigorous analysis” of Obama.

The four co-signers of the protest letter are no Wilentz, whose style of false equations, attacks, and denials resembles that of Donald Trump, albeit with a political orientation now firmly in the right wing of the Democratic Party. But these respected historians have given him and his arguments a credibility that is undeserved.

While the letter is described by its supporters as “opening” a debate over the role of slavery in American history, it is less an expression of that than a shot fired as part of a backlash against more than half a century of scholarship that has sought to recontextualize the history of American slavery, which, like all history, is never static.

Further, the letter reasserts the celebratory “consensus” history of the 1950s which accompanied the Cold War and McCarthyism—the “American Exceptionalism” which saw ideas and ideology transcending social classes and social movements and the U.S. as the center of all forms of progress and the model for all people. While this is not necessarily true of the signers’ published work, it is true of the letter.

Some Criticisms of the Critics

The letter as I see it is guilty of the “distortions” of which it accused the project. Its tone and language are insulting and dismissive. Here are some important excerpts:

The project is intended to offer a new version of American history in which slavery and white supremacy become the dominant organizing themes. The Times has announced ambitious plans to make the project available to schools in the form of curriculums and related instructional material. . . . These errors, which concern major events, cannot be described as interpretation or “framing.” They are matters of verifiable fact, which are the foundation of both honest scholarship and honest journalism. They suggest a displacement of historical understanding by ideology. Dismissal of objections on racial grounds—that they are the objections of only “white historians”—has affirmed that displacement.

It seems that the letter’s signers fear that the 1619 Project will reach and “indoctrinate” millions of students, just as right-wing conservatives—with whom they march along—actually do.

In the “HUAC school” of scholarship, context is ignored.

The first of several distortions falls under the tradition of what I call the “HUAC school” of scholarship. The authors have chosen examples and quotations from the Project articles without looking at the full context to “prove” their points. This is not unlike the way HUAC took quotations from Marx and Lenin to accuse those who were fighting to establish trade unions, enact social welfare legislation, and abolish segregation and lynch law of working to establish a “Communist revolution and dictatorship.”

As a historian I always look at the context in which events happen to understand the primary and secondary sources used to explain events. Scholarship and education are products of society, not vice versa. With this the letter might agree: however, their definition of context is mechanical or what Marxist students of philosophy would call metaphysical—static, seeing reality as either/or.

Another distortion is the implication that the articles of the 1619 Project represent a sweeping rejection of the American Revolution or the Civil War. Rather than a repudiation, the articles are a valuable contribution to a fuller understanding of both. (Nor are the articles the same in their analysis, as the letter implies.)

Marx, Lenin, and Ho Chi Minh, for example, all saw the American Revolution, along with the British Revolution which preceded it by a century and the French Revolution which followed it in a matter of years, as major positive forces in history. But they saw the American Revolution as a beginning and not an end—a revolution marching triumphantly through history.

While the articles of the 1619 Project do not focus on the positive aspects of the American Revolution, they seek to make slavery central to the history of the U.S., rather than simply either denying or marginalizing its effects on colonial development; the American revolution; the territorial expansion associated with what Thomas Jefferson called “a continental empire” and what the protégés of Andrew Jackson called Manifest Destiny; post–Civil War segregation and disenfranchisement; and the racist-influenced backlashes against New Deal and Great Society policies and the Obama presidency.

Should the 1619 Project be attacked for emphasizing history that has been omitted or marginalized?

In essence, the authors are challenging or negating much of the history which the protest letter seeks to defend and freeze in time, emphasizing instead what the history either omitted or marginalized. Should the Project be attacked for this?

Similarly, should historians of Native American peoples be attacked for emphasizing that the American Revolution ended British and French opposition to U.S. territorial expansion, resulting in the expulsion and killing of large numbers of native peoples in the hundred years of war against the “Indians” from the Constitution to Wounded Knee?

Regardless of the answer, the 1619 Project’s interpretation of history—even if and when it becomes the center of new synthesis—will not be the end of further analysis.

The letter’s reference to a perceived dismissal of “white historians” is also a major distortion. After all, generations of establishment scholars whose arguments the letter echoes have either omitted or condemned “white” Marxist and Communist scholars like Philip Foner and Herbert Aptheker whose pioneering work challenged an academic establishment which reflected rather than dealt critically with racist ideology. The work of these “white historians” lives on positively in the work of the Project scholars, as does the work of the late George Fredrickson, a distinguished non-Marxist “white historian” who in his analysis of “Manifest Destiny” called it “Master Race” democracy.

I myself am a Marxist “white historian” who routinely makes in my classes points that appear in the articles of the 1619 Project—the centrality of color racism and white supremacy to U.S. history as a model for the exploitation of not only African-Americans but also Latin Americans, Asian Americans, and selected European Americans who had to “earn” the privilege of being considered “white.”

I remember also in the late 1960s when the Civil Rights movement inspired critical study of slaveholders’ use of the Constitution to in effect strengthen slavery. To deflect these criticisms, establishment historians rose to stress the anti-slavery sentiments of the Constitution’s framers.

As for the arrogant accusation that the Project represents “a displacement of historical understanding by ideology,” the letter’s author and co-signers should examine their own “ideology.” The greatest danger to “historical understanding” has always come from those who deny that ideology informs their framework, selectively order documents to support their ideology, and then proclaim that the documents are the “verifiable facts” of history. The late novelist, playwright, and man of letters Gore Vidal called such historians “scholar squirrels” whose project is to accumulate and bury documents the way squirrels bury nuts and then claim the documents speak for themselves.

The authors of the 1619 Project, whose work adds to both scholarship and teaching, are doing what scholars should always seek to do—open new directions rather than touch up conventional wisdoms like a tailor dealing with the length and cut of trousers and skirts.

Where they differ from the letter’s writers is that they refuse to see the progress of the past as a barrier to further progress or to deny the contradictions of past progress or the effects on later events. In short, they refuse to refreeze the history of slavery.

Note

1. Beard was the most important figure in the progressive school of U.S. historical scholarship, which focused on the role of economic interests to understand politics and policy.

Editor’s note: See Part 2, Backlash from the “Left.”

Image: James Gibson, Creative Commons, BY-SA 2.0.

Join Now

Join Now