How woke is the U.S. working class? The good news: A recent study suggests that millennials are more likely than previous generations to self-identify as working class. The bad news: In the 2016 presidential election, 41% of voters with a family income under $50,000 voted for Trump.

The working class can’t be blamed for Trump’s victory. But more than 4 in 10 voters with a family income under $50,000 voted for a man who promised to repeal the Affordable Care Act. This fact alone shows that the working class is not woke enough. Raising class consciousness should be a top priority for left activists, and we need more ways to do it.

First, let’s examine the terminology. What’s “working class”? To most people in the U.S., the term indicates an income bracket: currently, families making less than $38,000.

To some, it’s a cultural marker that refers only to people with blue collar jobs. To others, including many millennials, the phrase means failure: the failure to make it into the middle class. It is a negative identification, one that says, “I thought I’d be better off by now.”

All three of these misunderstandings work against wokeness.

Class is wholly determined by one’s structural position within a given economic system

For Marxists, class is not defined by income, type of job, or degree of success. Class is wholly determined by one’s structural position within a given economic system; specifically, one’s relation to the means of production. If you do not own the means of production—if you depend on wages or a salary—you belong to the working class. If you do own the means of production, you belong to the capitalist class. Income and wealth are not decisive factors. The dividing line between workers and capitalists is drawn on the basis of shared economic interests. It’s in the interests of the capitalists to make and keep as much property, profit and power as possible. It’s in the interests of the workers for all power and resources to be shared.

But many working-class people have been taught to misunderstand their real economic interests. On the basis of this misunderstanding, they mistake the capitalists for their allies, and vote against themselves.

One of our best weapons in fighting such misunderstandings is our ability to analyze ideology. In a major contribution to Western thought, Marx revealed that prevailing beliefs and values, which we mistake for timeless truths, are actually “ideology.” That is, they are historically specific products that support the status quo. A precept as simple and seemingly obvious as “thou shalt not steal” supports certain assumptions about property rights and ownership, the status of things under capitalism. One can imagine a different society whose precept would be, “thou shalt share.” We don’t live in that one.

Marx, and the 20th-century Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, emphasized that ideology is not the intentional product of a few conspirators. The system of beliefs and behaviors encompassed by the term “ideology” is much too large and complex to be produced and controlled by any group of individuals. Rather, ideology is like an ecosystem in which we all live. It works to blind everyone to the social inequalities and class politics that underlie our successes, failures, privileges, and limitations. The capitalists are fooled into believing that the wealth and power they’ve acquired is rightfully theirs. So are the workers.

In a brilliant essay on ideologyAlthusser points out that in every generation, the conditions of production must be reproduced. Worn out tools and machinery must be replaced, software upgraded and so on, but also the workforce must be replaced. Workers must be taught techniques and skills, but more importantly, they must be taught “respect for rules of the order established by class domination.” For example, each child must learn that the United States has the best economic system ever; if people are poor it’s their own fault, and anyway the system is impossible to change. Such beliefs keep people docilely joining the status quo.

We learn and re-learn the rules through many channels

It’s not just schools that teach such ideological rules and reward us for accepting them. We learn and re-learn the rules through many channels, including mass media, culture (literature, the arts, sports), the family, social groups, religious institutions. Althusser calls these “Ideological State Apparatuses” (ISAs). They are supposed to work together to perpetuate beliefs and behaviors that reproduce existing distribution of wealth and power. But they do so very quietly and subtly. The system works best if we believe we are freely choosing, making up our own minds, not being forced into something.

Ironically, the people who truly believe that America is the land of freedom and free choice have been the most effectively subjected to ISAs. Their minds have been molded to regard this idea as a simple truth, even though their own firsthand experience contradicts it. Such examples hint at the power of ideology.

Althusser differentiates ISAs, which operate subtly, from a different type of power, the “Repressive State Apparatus.” Repressive power consists of government, police, army, courts, and prisons; it functions by violence and forcible, visible repression or coercion. It is completely controlled by the ruling class, except in a time of revolution, and functions as backup when ISAs fail. For example, schools teach students that our criminal justice system is fair and unbiased. But if the students do not learn right and take to the streets to protest dramatic racial injustice, they can be arrested by the police and sent to jail.

Yet the fact that such things do happen demonstrates that the ISAs are fallible. They never work perfectly to support the capitalist status quo. Some people are woke, able to think critically about the messages the ISAs are sending and offer opposing views. They keep the ISAs from forming one big happy brainwasher, and make them into a complicated, ever-shifting set of battlefields.

The ISAs, then, are not something we fight against, but something we fight within. They are sites of struggle because, as Althusser puts it, “former ruling classes are able to retain strong positions there for a long time, but also because the resistance of the exploited classes is able to find means and occasions to express itself there, either by the utilization of their contradictions, or by conquering combat positions in them in struggle.”

Consider the example of music. If you press “scan” on your car radio, you might hear a Beethoven symphony that was once used to distinguish the educated aristocracy from the upstart bourgeoise factory owner. Then comes a Top 40 station with its love songs and laments, all stressing that one should focus on private life and forget about politics. Another station plays Springsteen, Bob Dylan, and Aretha Franklin, past anthems of social protest now coated in nostalgia, though they still bear witness to the anger that bore them. Then you might hit a college station playing new protest music: Mona Haydar, Chicano Batman, M.I.A. As Althusser put it, the ISAs are “not only the stake but also the site of class struggle.”

Over the past decade, progressive forces have made great use of television, presenting strong positive images of women, people of color, differently abled, gay, lesbian, or trans. These fictional characters have had a huge impact, helping drive some conservative ideological forces into retreat. Though difficult to prove, it seems very likely that the shows have helped bring about material change, such as the legalization of gay marriage. Unfortunately, class struggle has been less widely portrayed on TV. As access to production and distribution mechanisms opens up, activists should seize opportunities to create representations that further class consciousness. We can also draw attention to images that do exist and help people interpret their meaning.

Not all revolutionary battles happen in the realm of ideology

Granted, not all revolutionary battles happen in the realm of ideology. Material struggles over economic structures and political power are ultimately more important. But raising class consciousness means finding allies so that material struggles can be waged and won. We need to identify spaces within ideology where working-class identity is being contested, and devise interventions. Ideological struggles are dynamic and fluid. Images that were derogatory can be appropriated as symbols of power, or vice versa. An important site of struggle may suddenly become irrelevant. Therefore, ideological analysis always has to be done anew, for the here and now.

Right now, a very dangerous ideological battle is being fought over what it means to be a white working-class man. Trump and his allies have shaped an enticing fantasy for this particular population, promising to restore their lost economic and social power by taking back the rights of Others (women, ethnic and religious minorities, immigrants, the LGBTQ community). Of course, working-class men never had economic or social power. That doesn’t stop the enemy from representing it as lost, stolen. In this fight, the far right portrays race, religion, gender, and sexuality as decisive dividing lines, blocking any perception of shared interests based on class.

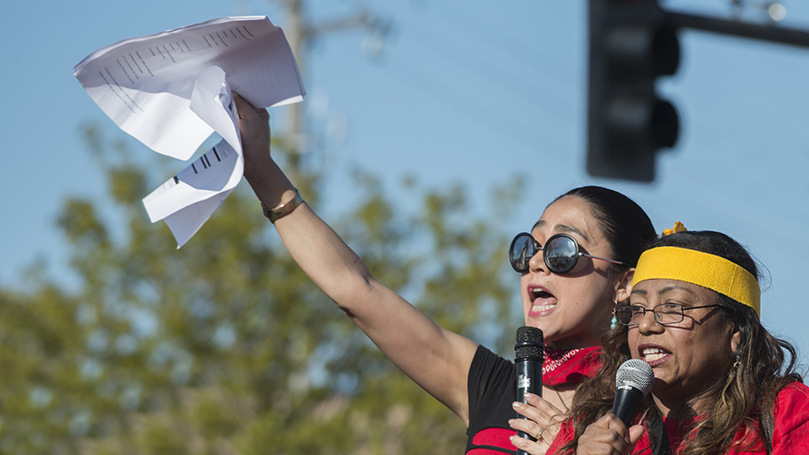

The left has relied heavily on critique to fight back. Critique is important: we must expose lies and reveal contradictions. But it isn’t enough. Now more than ever, the working class needs positive ideals, competing representations that position working-class identity as attractive and embraceable. Communists and socialists actually have positive ideals to offer, a great advantage over our liberal allies. We need to use this advantage to maximum effect. Fight back by presenting images and stories of alliances based on class. Look for opportunities to redirect ideological assertions. Their rhetoric promotes the belief that white men have been robbed of power and relevance. Our rhetoric promotes belief in an inclusive future that will be more rewarding for everyone. They tell a story of lost power and create opportunities for the violent expression of rage and hatred. We tell a story of exciting discovery, and create opportunities to learn from and respect each other.

One way of creating such opportunities was developed by the women’s movement in the 1970s. At that time, it was common for women not to feel solidarity with other women, and not to accept that sexism was real. Feminists brought women together in “consciousness raising” groups to share their experiences. “I have never been subjected to sexism,” a woman might say. “I do have varicose veins from wearing high heels, a husband who does no housework and ridicules the books I like, and a minimum wage job at a day care. But those things are just my own individual life choices.” As women listened to other women, they began to see their common experiences as products of an oppressive system. At the same time, fellowship and camaraderie with other women made the identification rewarding: “Sisterhood is a warm feeling!” This affirmation re-defined what it meant to be a woman, changing the affective value of the identification from something demeaning to something positive and celebrated.

Strong working-class identification provides the unifying factor that makes other aspects of identity a matter of diversity

The same method might work to raise class consciousness. In a diverse group, facilitators could ask whether participants have ever been injured at work, whether they are able to save money, take time off for family, own a house or pay for college without debt, and also whether their bosses can do these things; what percentage of revenue the company would lose without the worker, and how this compares to the worker’s wages; whether the boss deserves to have more money and power, etc. Questions that might seem demeaning in an individual conversation have a different effect in a cohort group, where the pleasures of solidarity can make working-class identification rewarding. The answers people say and hear will validate firsthand experience, allowing the representation of firsthand experience to gain power over false ideological precepts. (“Wait a minute! That’s not right. That’s not fair.”)

Such groups can lead participants to see class similarities across racial and ethnic divides. This requires an upstream paddle against the many enticements of ideological forces urging us to understand ourselves in other ways, ways that divide the working class but may be more attached to privilege or at least to pride, community and belonging. But again, the widespread failure of people to identify themselves in a primary sense as workers, having interests in common with all other workers, is a major obstacle to progress. Class identification does not preclude others (ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, profession, etc.). But a strong working-class identification provides the unifying factor that makes other aspects of identity a matter of diversity rather than division.

In the past, Marxists embraced a simpler opposition between capitalist ideology and workers’ material reality, or truth. Ideology was the enemy and truth was the weapon. But life in the 21st century is fully soaked in representations, and representations are always ideological. It is no longer possible, if it ever was, to separate reality from ideology. We can’t simply pop ourselves out of the tight network of images and practices, hopes and fears that keep people believing, for example, that we all have an equal shot at the top. To contest this imaginary relationship to an exploitative reality, we have to work within the network, using the tools it provides. Class struggle against pro-capitalist ideological forces must take place within ideology. In addition to critique, we need positive representations of working-class identity to raise class consciousness and compete with the far right.

Join Now

Join Now