Editor’s note: This foreword is reprinted from My Life as a Political Prisoner by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, with permission of International Publishers.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a bona fide American radical. Born in 1880 to an Irish mother and Irish American father in Concord, New Hampshire, she began her activist career as a Wobbly, joining the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) when she was just sixteen years old, and she ended it as the first female chair of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), a position she held from 1961 until her death in 1964. In the intervening years she led organizing drives and strikes in a variety of industries around the country and demonstrations on behalf of the unemployed; orchestrated free speech fights to challenge local ordinances that criminalized speaking with a pro-labor message; provided material aid and access to legal counsel for countless individuals imprisoned for their pacifism, political views, and/or work for the labor movement before, during, and after World War I; campaigned against deportation of immigrant labor activists during the first Red Scare; supported anti-imperialist movements in Ireland, India, Mexico, and elsewhere; championed reproductive rights for women; called for the organization of black workers into integrated unions; spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan in the US and fascist movements worldwide; ran for elected office in New York City; and advocated for freedom of conscience for all Americans during the Second Red Scare. It is no exaggeration to claim that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was involved in almost every major campaign of the US Left in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a bona fide American radical. Born in 1880 to an Irish mother and Irish American father in Concord, New Hampshire, she began her activist career as a Wobbly, joining the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) when she was just sixteen years old, and she ended it as the first female chair of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), a position she held from 1961 until her death in 1964. In the intervening years she led organizing drives and strikes in a variety of industries around the country and demonstrations on behalf of the unemployed; orchestrated free speech fights to challenge local ordinances that criminalized speaking with a pro-labor message; provided material aid and access to legal counsel for countless individuals imprisoned for their pacifism, political views, and/or work for the labor movement before, during, and after World War I; campaigned against deportation of immigrant labor activists during the first Red Scare; supported anti-imperialist movements in Ireland, India, Mexico, and elsewhere; championed reproductive rights for women; called for the organization of black workers into integrated unions; spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan in the US and fascist movements worldwide; ran for elected office in New York City; and advocated for freedom of conscience for all Americans during the Second Red Scare. It is no exaggeration to claim that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was involved in almost every major campaign of the US Left in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century.

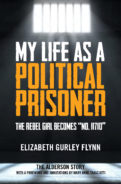

Despite a long and storied career as a class warrior, Flynn is not a widely known historical figure among contemporary activists. When people do think of her the first image that comes to mind is the Rebel Girl. A young, slender, raven-haired, fearless firebrand, wearing a black skirt, white shirtwaist, and red tie, she stands on a makeshift outdoor platform or a street corner soapbox thrusting her finger into the air, and holding a crowd of striking workers—men and women, young and old, immigrant and US-born—spellbound while she vilifies “the bosses” and mocks police who uphold their laws. A thorn in the side of local law enforcement around the country, the Rebel Girl had a preternatural ability to get herself out of trouble whenever she ran afoul of the law. This was not the Elizabeth Gurley Flynn who spent twenty-eight months in the Alderson Federal Women’s Reformatory from 1954 to 1957. The Flynn of Alderson, also known as Prisoner Number 11710, was a heavy-set, gray-haired, elderly woman in a matronly dress who looked a lot like my Irish American grandmother.

But appearances can be deceiving. Although she was no longer a girl, Prisoner Number 11710 was still a rebel. She had long since left the IWW and joined the Communist Party where she continued to rail against greedy bosses and rapacious capitalism, as well as fascism, racism, sexism, and a host of other evils, but she was more likely to make her case in the pages of the Daily Worker than in a rousing speech at an outdoor meeting. In 1951, at the age of sixty-one, Flynn was one of 132 “second tier” Party leaders indicted under the Smith Act for allegedly advocating the overthrow of the government by force and violence. She acted as her own counsel and spoke eloquently in defense of the right of all Americans to their own political opinions. Sympathy for the cause of free speech, especially for Communists, was not in great abundance in the fraught atmosphere of the Cold War, however, and she was found guilty and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. Two other women were convicted along with her: Claudia Jones, a Trinidad-born journalist, feminist, Black nationalist, and member of the National Committee of the Communist Party, and Polish immigrant Betty Gannett, a teacher, writer, and National Education Director for the Party. A third woman, Marian Bachrach, was severed from the trial to undergo cancer surgery.

My Life as a Political Prisoner: The Alderson Story (originally titled The Alderson Story: My Life as a Political Prisoner) is Flynn’s account of her experiences behind bars. Published in 1963, nearly six years after her release from prison, it was her second book. She wrote her first book, I Speak My Own Piece: Autobiography of “The Rebel Girl” during her Smith Act trial. (Nearly a decade after her death the book was reissued by International Publishers with a new title: The Rebel Girl: An Autobiography, My First Life (1906–1926)). Although her autobiography is by far the more well-known of the two books, Flynn’s prison memoir is the more complex work, and it deserves a wider audience. At once a detailed account of everyday life in a women’s prison, a call for prison reform, and a narrative of resistance, there is much in the book that will resonate with contemporary readers.

The narrative begins with Flynn’s arrest at the hands of three FBI agents who stormed into her family’s New York City apartment “on a hot morning in June 1951” (9). But the book is not about the excesses of Cold War anti-Communism or the Smith Act. The trial and appeals process are addressed in two very short chapters, and by the beginning of Chapter 3 we have arrived, along with Flynn, Jones, and Gannett, at Alderson. The first federal women’s prison in the United States, Alderson was founded in West Virginia in 1927. It was intended to be a place of regulation and reform, rather than punishment, and the grounds were modeled after a boarding school, with fourteen cottages arranged in a horseshoe pattern, each with its own kitchen. There were no barbed wire or armed guards. Inmates were there for mostly minor offenses related to drug and alcohol use.

As Flynn notes, a prison without barbed wire, even one in a beautiful rural setting, is nonetheless a prison. Although the physical space remained basically unchanged, by the time Flynn got to Alderson the reformatory spirit had waned considerably.

Little by little there was a tightening of rules, the privileges shrunk. . . . Confidence in the women, which had brought out the best in even the worst of them, was now replaced by distrust and suspicion, an atmosphere in which the inmate was always wrong. All forms of initiative were discouraged. (110)

Flynn drew upon her excellent memory, no doubt honed by years of extemporaneous speaking, to present a vivid picture of life in Alderson. Her tenure there began with what she called “the depersonalizing process” (25). First, a strip search, followed by an enema and a search of all bodily cavities. Then, a shower, after which the new inmates were handed a rayon nightgown and a brown housecoat “of rough, nondescript material” (25), photographed and fingerprinted, and quarantined for three days. Her evocative writing transports us across space and time and lets us see Alderson in our mind’s eye. We learn that there was a dog kennel near the prison; the furniture in the lock-in rooms consisted of a toilet, wash bowl, bed, radiator, and a small cast-iron chest with a shelf and two doors; and a mother skunk with babies once paid a visit to the inmates. In addition to conveying the materiality of the experience with quotidian details, Flynn captured the psychological effect of incarceration. As we read her story we get a sense of what it felt like to be denied one’s freedom. Reflecting on her orientation, for example, she observed, “The heavy shadow of prison fell upon us in those three days—the locked door and the night patrol. The turning of a key on the outside of the door is a weird sensation to which one never became accustomed. One felt like a trapped animal in a cage” (27).

As Alderson transformed from a reformatory into a prison it became increasingly militarized. Flynn observed that many of the female prison officials she encountered had been in the army during World War II. They brought a military mindset and military language with them into the prison. Guards and wardens were referred to as officers, with the high-ranking among them having titles of Captain or Lieutenant. The long arm of the US military did not stop at prison personnel; it reached into every aspect of prison life. The first three weeks of a new inmate’s stay were called “orientation,” following military usage. Like new military recruits, new inmates were classified and assigned a work detail based on a medical checkup and intelligence and aptitude tests. Inmates’ clothing came from Army surplus (blue pants and jackets from the WAACs and seersucker dresses from the WAVES). Dishes had the insignias of army, navy, and medical corps. The “militarization creep” that Flynn described at Alderson rings all too familiar in an era in which war abroad is a constant backdrop, and at home military-grade weapons are readily available to just about anyone who wants one, while unarmed peaceful protestors are routinely met by police in riot gear.

Contemporary readers will also recognize the profile of Alderson’s prison population: mostly poor and working-class—as she noted in her characteristically wry style, “no rich women were to be found in Alderson” (37)—majority black and Spanish-speaking, many from abusive backgrounds, some mentally ill or suffering from drug addiction. Inmates and guards were racially segregated when the prison was founded, and the situation had not changed by the time Flynn arrived. Claudia Jones was assigned to a segregated “colored cottage.” Significantly, after the Supreme Court declared segregation unconstitutional in its 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Flynn, Jones, and other Communists were called upon by prison officials to help integrate the prison houses. Flynn clearly reveled in the irony of Communists being asked to enforce a civil rights edict issued by an arm of the US federal government. (Another irony: she was invited by prison authorities to write a “patriotic article” for the 4th of July issue of the 1956 Alderson Eagle.) Although she and her comrades could not eradicate the structural racism that pervaded the prison, their interventions and educational efforts helped build trust and improve relationships among white, black, and Latina inmates.

Flynn’s solidarity with the oppressed and unwavering commitment to social, political, and economic justice reverberate throughout the pages of her prison memoir. Never one to waste an opportunity for activism, she used her time at Alderson to get to know the women around her, understand how and why they ended up in prison, and use this knowledge to advocate on their behalf. She presents fellow inmates as complex individuals whose crimes more often than not were the consequence of struggling with limited resources against forces beyond their control. Rather than punishment these women needed social policies that addressed the dire circumstances in which they lived. To this end Flynn advocated for the decriminalization of prostitution, and in an era in which drug addiction was widely viewed as a form of criminality rooted in moral weakness she instead recognized that it was an illness and called for the creation of federally funded outpatient clinics for treatment. Her time in Alderson preceded second-wave feminism, but a lifetime of activism had ingrained in her the realization that “the personal is political.” While at Alderson, Flynn lived her political commitments in the small acts of kindness she performed, such as encouraging her outside correspondents to send her greeting cards and picture postcards, written in pencil, which she then erased and gave away to be used as room decorations.

Regrettably, Flynn’s capacity for empathy and understanding did not extend to lesbians at Alderson. In cringe-worthy passages that seem woefully out of sync with the rest of the book, she decried sexual and romantic relationships between women inmates as degenerate and perverse. She was especially hard on women who desired to look and act masculine. For example, although she was a skilled sewer and often asked to mend or make clothes for fellow inmates (her job assignment was to do mending), she made it a rule “not to alter slacks or shirts so as to masculinize them” (85).

Why was Flynn so hostile to lesbians at Alderson? One answer is that her views reflected those of the Communist Party at the time. The Party’s homophobia was one area in which it was in lockstep with mainstream America. Homophobia and anti-communism were two sides of the sword that was used to cut down “deviants” and subversives during the second Red Scare. Political rhetoric linked Communists and gays, alleging that both were morally weak, psychologically imbalanced, indecent, shadowy figures looking to convert others to their deviant ways, undermine the traditional family, and overturn society. But there may also have been a more personal motive. In 1926, Flynn’s emotional and physical health was compromised when she learned that her younger sister, Sabina, and her lover, Carlo Tresca, had an affair while the three were living under the same roof. To recuperate mind and body, Flynn left for Oregon and moved in with a friend, Marie Equi. A physician, pacifist, suffragist, and birth control advocate, Equi was also an out lesbian. She and Flynn lived together until Flynn returned to New York, where she joined the Communist Party in 1936. Scholars have speculated on the nature of the relationship between Flynn and Equi, and it could be that Flynn took a hard-line public position on homosexuality to deflect attention from questions about her own sexuality. Whatever her reasons, she presented a portrait of a menacing, sexually aggressive “prison lesbian” that was as familiar to her comrades as it was to those Cold Warriors who wanted nothing to do with a book written by a jailed Communist Party leader.

Flynn’s exploits had received widespread media attentions since she delivered her first soapbox speech in New York City and was arrested for blocking traffic while railing against the excesses of capitalism in 1906. Her imprisonment and release from Alderson were no exceptions. Both were headline news. In contrast, unless cited as confirmation of the “problem” of lesbianism in female prisons, her prison narrative received relatively little attention from mainstream media. No surprise there. The book described a legal system organized around arbitrary and senseless rules in which the adequacy of one’s counsel was commensurate with the size of one’s bank account, and a prison regime that disregarded the most basic rights and human decency of those in its charge, condoned racial discrimination, meted out cruel and unusual punishment for minor offenses, exploited inmates’ labor while disregarding their physical and psychological well-being, and provided little opportunity or incentive for rehabilitation. In the fraught atmosphere of the Cold War when the US was presenting itself to the world as the last, best hope for freedom and democracy such an exposure of the underbelly of American “justice” was politically inexpedient, to say the least.

In its 1963 review the American Library Association praised Flynn’s factual, rather than emotional, tone and noted that although “her plain speaking will disturb some readers . . . this recreation of the McCarthy era . . . and her suggestions pertaining to penal reform will interest the objective-minded layman.” The same year, Saunders Redding, writing for the Baltimore Afro-American, noted approvingly that Flynn did not push “the Communist cause” but showed a commitment that was larger than Party by concerning herself with “young and salvageable women whose primary crime in many instances is a kind of social ignorance.” Other reviewers were less positive. According to Edna Brawley in the Daily Independent, a North Carolina newspaper, “Her book is supposedly a plea for prison reform, but comes through mainly as an attempt to whitewash her activities and those of her associates.” As might be expected, reviews in Communist publications were glowing. For example, Political Affairs, the Party’s political journal, deemed it “high in human interest and important as to its subject.”

Arguably, the book’s most enthusiastic readers in the US were progressive social workers, who hailed it as a clarion cry for prison reform. Two of them—Jessie Binford and Bertha Reynolds—felt so strongly about its importance that they organized the Committee to Bring the Alderson Story to Public Attention. Calling the book “an unusual document from the closed world of a women’s prison” and “a living page of history,” Binford and Reynolds wrote social workers around the country urging them to put aside their political preconceptions, read this “account of women without a voice to speak for themselves,” and be stirred to “more thought and really concerned action.” In addition to these motivated social workers, distribution in the US relied on the Party’s network and Flynn’s personal contacts from a half century of activism. These contacts were numerous and varied. Although Flynn never wavered from her convictions, she was no ideologue. On the contrary, she had a rare ability to find common ground even with people whose politics diverged from her own. A case in point: she sent an autographed copy of The Alderson Story to Judge Edward Dimock, the man who’d sentenced her to prison! In the book she made it clear that she respected Dimock. If his letter in response to receiving his copy is any indication, he reciprocated.

To celebrate the author and the publication of The Alderson Story, a group that called itself Friends of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn hosted a reception at the Belmont Plaza Hotel in New York City on March 29, 1963. Members of the committee that sponsored the book release party included comrades Betty Gannett; Claudia Jones, who was living in England, having been deported there upon her release from Alderson; and Alexander Trachtenberg, founder of International Publishers; as well as prominent activists who shared Flynn’s commitment to social justice, if not her Party affiliation. Among the latter group were Warren Billings, a fellow traveler from Flynn’s Wobbly days, who, along with Tom Mooney, was wrongly convicted of the San Francisco Preparedness Day bombing of 1916; John Haynes Holmes, Unitarian minister and founder of the ACLU; Rockwell Kent, acclaimed artist, and his wife Sally; and Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement. The event was nearly cancelled by the Belmont Plaza when a right-wing political organization, the Nationalist Party, threatened to picket, but an order from the New York State Supreme Court forced the hotel to honor its contract. Greetings and salutations came from around the US and the world. Such luminaries of the Left as Irish playwright Sean O’Casey and Dolores Ibárruri, “La Pasionaria,” whose courage and eloquence inspired the anti-fascist cause during the Spanish Civil War, chimed in, as did comrades from Canada, Mexico, the Soviet Union, and Hungary. Because the Communist Party of the United States was part of an international movement, The Alderson Story enjoyed global visibility, even if Cold War politics limited its reception in the US. Dietz Verlag, a publishing house in East Berlin, released a slightly edited, translated version in 1964. Autographed copies of the English version went to comrades in Canada, France, England, Russia, and elsewhere.

Flynn’s commitment to internationalism and the solidarity of workers around the globe was matched by a strong affinity for the country in which she was born. Like her friend and mentor James Connolly, she saw no contradiction between love of country and revolutionary working-class politics. On the contrary, in a letter to her sister Kathie days before her release from Alderson, she wrote:

Nothing and nobody can take my country away from me. I sit in prison, thinking of its beauty, its breadth, its people. It is ever in my heart, my thoughts, my eyes—its growth, its vastness, its richness. Sitting in the twilight, watching the sun sinking in the West, I remember my country clear out to the Pacific Ocean. (197)

That these words were penned by one of the most radical anti-capitalist, anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-imperialist, anti-sexist activists born and raised in the US may strike contemporary readers as unusual. By now we are accustomed to a US Left that all too often relegates love of country to the province of xenophobes, misogynists, and racists. That is not to say that Flynn loved the US unconditionally. She loved its good people, its natural beauty (were she alive today, she would surely be a climate activist), and its potential, as evidenced in documents like the Bill of Rights, which she defended throughout the entirety of her activist life. The title (originally the subtitle) of her memoir suggests as much: My Life as a Political Prisoner. Unlike many other countries the US does not, and never has, recognized political prisoners. Flynn had been fighting for that recognition for others since her days with the Workers Defense Union, which she organized in response to the federal government’s roundup of labor activists under the Espionage Act during World War I. If the federal government refused to accord her the status of a political prisoner during the Cold War, no matter, she bestowed it upon herself. “Come what may, I was a political prisoner and proud of it, at one with some of the noblest of humanity, who had suffered for conscience’s sake” (29). In her choice of words Flynn signals that her prison memoir is a narrative of resistance. Rather than accept the label of “criminal” imposed upon her by the Smith Act, she rewrites herself and, by extension, all Communists as idealists whose only “crime” was holding their country up to its own promise. She identified the Puerto Rican nationalists in Alderson as political prisoners for the same reason.

Being a Communist political prisoner meant that Flynn, along with Claudia Jones and Betty Gannett, suffered discrimination at the hands of some of the prison guards (and Jones, of course, suffered discrimination for her race), but it also had its advantages. Whereas most of the women received few if any letters and were penniless or sent at most a couple of dollars from home, the “politicals” got visitors as well as letters and always had funds on hand, donated mostly by the Families’ Committee of Smith Act Victims. It was against the rules to give money away or to buy things from the commissary for other prisoners, but the “politicals” regularly did so. Their sharing amounted to a type of mutual aid, which was itself a time-honored performance of solidarity and resistance among the working classes.

For me, passages about being a political prisoner are among the places where Flynn’s personality shows itself most clearly. “I was (and am) a leading American woman Communist” (116), she noted with a touch of indignation when recounting time she spent sequestered in maximum security. The effect is not to suggest that she imagined herself somehow better than the other inmates; quite the contrary, she is lifting the curtain a bit and providing a glimpse into the kind of thinking that enabled her to survive three years in prison simply for holding and defending a set of political beliefs she’d held and defended for over half a century. It could not have been easy to be an older woman radical, especially when so much of Flynn’s reputation was tied to the youthful vitality and irreverence of the Rebel Girl. Even if she weren’t haunted by the specter of the Rebel Girl, there were few categories to describe older women political activists in the 1950s and 1960s, a situation that hasn’t changed very much in the intervening years. Unlike Mary Harris Jones and Ella Reeve Bloor, Flynn refused the “mother” sobriquet. Motherhood was one of the few places in her life where the personal and the political remained separate. In what is perhaps the most poignant passage in the book, she recalled, “On one thing I was adamant. I allowed no one to call me ‘mom.’ I explained that I had lost my only son and I could not bear to hear the word, which sufficed to stop it” (174).

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn died in Moscow a year after The Alderson Story was published. In the years before and after her death, her association with the CPUSA was used by anti-Communists of various stripes to delegitimize her significant contributions to labor, civil liberties, anti-fascist, feminist, and civil rights struggles, and the generational shift from Old to New Left seemed to leave her behind. The time is right for a revival of Flynn’s story and a reassessment of her important legacy. As a newly energized US Left continues to develop into a real political force in the wake of Cold War, with grassroots campaigns around issues such as income inequality, universal health care, affordable housing, immigrant rights, sexual violence, and racial injustice, and a growing number of electoral victories, her activist life and career can serve as a model and inspiration. Republication of her Alderson memoir couldn’t come at a more opportune moment. Read it. Critique it. Share it. And all hail the rebel, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn!

Image: Flynn speaking at 1913 rally of Paterson silk strike workers, Daily Worker / People’s World Archives

Join Now

Join Now