While there is much food for thought in Michael Goldfield’s article “100 Years of American Communism,” there is also a critical omission. Glaringly obvious is the absence of the Communist Party during the second half of the 20th century, during the second half of its 100-year existence. As a result, Goldfield’s article perpetuates the dominant narrative within U.S. historiography, a narrative that suggests the demise of the CPUSA post-1956.

I don’t agree with everything in the article, but Goldfield is correct when he writes that the CPUSA was “from at least the early 1930s until the 1950s, the preeminent left group in the country, and one with no significant rivals.” He rightly highlights the role of Communists in the Unemployed Councils, the National Negro Congress, the American Youth Congress, the birth and organizing of the CIO, etc.

He correctly adds that the “CP was the first largely white US radical group to focus attention on the plight of blacks.” Its leadership in defense of the Scottsboro Nine is but one well-documented example.

Goldfield’s analysis of the CPUSA during the third period as well as its less than critical view of the Soviet Union is fair. Though his omission of the organizing of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade as well as the CPUSA’s contributions toward the defeat of fascism (an estimated 15,000 Communists served in the armed forces) in World War II strikes me as odd.

Unfortunately, though, Goldfield’s post-1956 omission leads to a false claim, a claim that does not square with the historical record, that is, that by the 1950s the CPUSA “was easily blown away with nary a trace.”

Those less sympathetic to socialism have argued for decades that the CPUSA was a “shattered organization,” it was “afflicted with a mortal illness,” and played a negligible role after 1956 as its “membership plummeted.”

Goldfield quotes James Weinstein, a “bitter detractor,” who notes that “the Communist Party was not only the largest and best organized party on the Left, but for all practical purposes it was the socialist left.” Of course, Weinstein qualifies this otherwise correct statement with “until 1956 or so.”

The CPUSA was undoubtedly weakened post-1956. This isn’t in dispute. But it was not “blown away.” Far from it.

A little context: after nearly a decade of political repression through the Smith and McCarran Acts, and McCarthyism generally, as well as through internal “security measures” (the elimination of membership lists, for example), factionalism, the loss of members due to the Khrushchev revelations and the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution, etc., the CPUSA was indeed much weaker than it had been in 1948 prior to the first indictments of its leadership.

Many of its leading cadre spent most of the early 1950s underground or in jail—or deported. Goldfield’s minimizing of the political repression faced by Communists and their allies is ahistorical.

However, despite the repression, the Party-led Civil Rights Congress (CRC), Council on African Affairs (CAA), as well as the International Workers Order (IWO) continued to champion the struggle for African American equality, anti-colonialism, and the building of fraternal mutual benefit societies, respectively; by mid-decade all were forced to dissolve. Even if just briefly, Goldfield should have mentioned these organizations and their impact: the CRC’s defense of Willie McGee; the CAA’s cross-Atlantic solidarity with the African National Congress; the IWO’s attempt to build a multi-racial benefit society. Never mind the contributions Communists made in the realm of popular education with their flagship adult education institution, the Jefferson School for Social Science.

Regardless, by 1959 domestic communists had regrouped and decided to focus their energy on youth and students. Party-led youth organizations such as the Advance Youth Organization and the Progressive Youth Organizing Committee, the publication New Horizons for Youth, and by spring 1964 the W.E.B. DuBois Clubs (DBC)—named after the African American activist-scholar who in 1961 officially joined the CPUSA—would soon emerge.

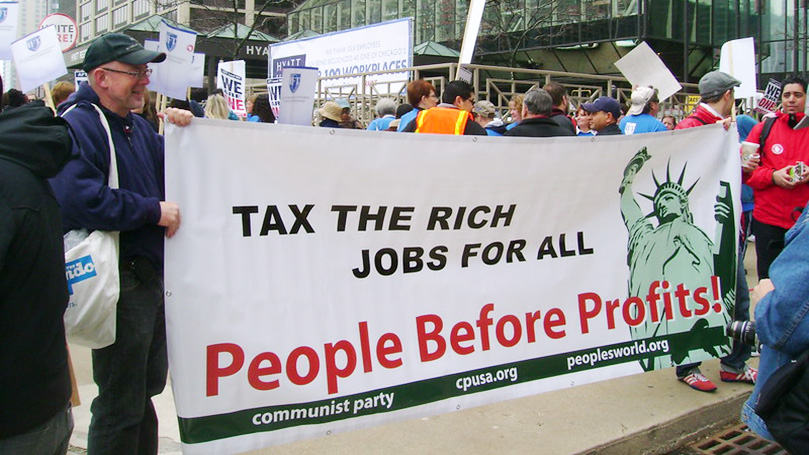

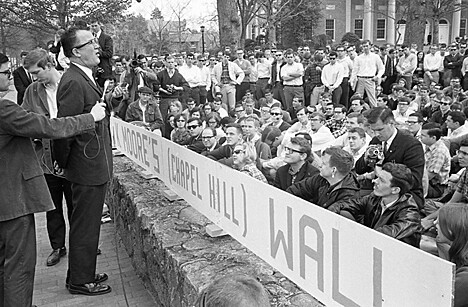

Additionally, Communists embarked upon a wave of wildly successful university and college speaking tours. For example, from February 10 to 15, 1962, CPUSA general secretary Gus Hall spoke with a cumulative 19,000 students on five campuses. Other Communists, like Herbert Aptheker, James Jackson, Frank Wilkinson (pictured above), and Dorothy Healy, were also met by thousands of students fighting for their right to hear Communists speak.

By mid-June 1962, Hall declared, “During the past six months I have spoken to some 50,000 students and youth directly. . . . The tide has turned.” That September, the Party’s Lecture and Information Bureau would note that in “the past year Communist spokesmen addressed more than thirty colleges and universities . . . approximately 75,000 students and townspeople” attended.

It is estimated that CPUSA leaders spoke with at least 100,000 youth and students between fall 1961 and summer 1964. Communists didn’t just passively benefit from the upsurge. They added kindling to the fire.

Adding to their optimistic assessment, between 1964 and 1966 over 120,000 votes were cast for Communist candidates in Los Angeles alone, despite ongoing political repression, harassment, and intimidation.

By fall 1964 the Berkeley Free Speech Movement emerged and propelled young Communist Bettina Aptheker into the spotlight as a national leader of the youth and student upsurge. Aptheker would later help lead the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, or Student Mobe, and propose the April 1968 student strike in which an estimated million students participated.

Communists and Du Bois Club members made their mark on the civil rights and peace movements, too. Many, like Debbie Bell, Phillip Davis and Cassie Lopez worked for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, while others helped organize Women Strike for Peace, which challenged the House Un-American Activities Committee by defiantly welcoming Communists as equal partners into the growing peace movement.

In 1965, CPUSA leader and Marxist historian Herbert Aptheker led a delegation to Vietnam that included Yale professor Staughton Lynd and Students for a Democratic Society leader Thomas Hayden. There they met with the prime minister of the Democratic Republic of (North) Vietnam and representatives of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover considered Aptheker “the most dangerous Communist in the United States” due to his presence on college and university campuses; to students, Aptheker was considered a Left celebrity.

In 1966 the Fort Hood Three became the first G.I.s to publicly refuse to deploy to Vietnam and thereby helped spark the organized G.I. anti-war movement. That two of the three were CPUSA members is illustrative of the broad tactical approach of Communists.

By 1968 Communists would again make history when CPUSA leader Charlene Mitchell (pictured above) became the first African American woman to run for president of the United States. While Communists did not expect or receive a huge vote, Mitchell’s campaign challenged the two-party electoral system—its racism, sexism, and ageism, a system we have yet to substantively alter.

The impact of the Party-led quarterly publication of Black liberation Freedomways has yet to be fully analyzed and appreciated. It remained a potent political tool by which Communists continued to gauge and influence African American political discourse well into the 1980s.

In 1969 over 1,500 students called for a general strike throughout the University of California system in support of the recently dismissed Communist professor Angela Davis. The Davis frame-up and trial, the worldwide defense—led by Communists—as well as her ultimate acquittal is so well known it doesn’t warrant discussion here. However, what came after does: the birth in May 1973 of the Communist-led National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR), which helped lead the fight to free JoAnne Little and Frank Chapman, among other victims of racist and political repression, like Ben Chavis and the Wilmington 10.

National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression chapters emerged across the country and continued as a potent political force well into the 1980s; NAARPR was re-founded earlier this year.

Also, in 1973 Communists founded the National Anti-Imperialist Movement in Solidarity with African Liberation (NAIMSAL), which helped lead the domestic divestment movement against apartheid South Africa. At NAIMSAL’s founding convention, African American Party leader Henry Winston—who was considered “the moving force” behind the organization—called for a “massive anti-imperialist movement to compel the unseating” of South Africa from the United Nations, as well as imposing comprehensive mandatory sanctions against the racist regime.

Like the NAARPR, NAIMSAL chapters were established across the country and organized solidarity actions with African National Congress and South African Communist Party leaders, often in defiance of the State Department.

Communists would also help found and lead Trade Unionists for Action and Democracy (TUAD) and edit the newspaper Labor Today, which helped initiate rank-and-file movements against labor’s conservative—perhaps, reactionary—old guard.

Throughout the early 1980s and 1990s, hundreds of thousands of people cast ballots for Communist candidates. In 1980, Rick Nagin, the Party’s steel coordinator based out of Cleveland, received over 42,000 votes as a candidate for U.S. Senate, while Barbara Browne, running for trustee of the University of Illinois, received nearly 47,000 votes; 92,000 votes were cast for Communist candidates in Illinois alone that year. In 1982, Communists received 36,000 votes for state treasurer in Minnesota and 28,000 votes for the board of education in Michigan. In 1983, the African American Communist Kenny Jones became the alderman of the 22nd Ward in St. Louis, where he helped lead the anti-apartheid divestment movement; Jones, an iron worker, was also a leader of the St. Louis chapter of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, then known as a red chapter. In 1990, as socialism was collapsing across Eastern Europe, Southern California Party leader Evelina Alarcon received 144,000 votes in her bid to become CA Secretary of State. And in 1997, Denise Winebrenner Edwards was elected to the Wilkinsburg, PA, city council. Though few in number, Communists today hold elected office across the country.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, as well as the aftermath of the 1991 split, Communists went through a period of retrenchment. But by the late 1990s and early 2000s, CPUSA leaders like Judith LeBlanc would blaze another important—and neglected—trail in U.S. history, further belying the myth of the Party’s demise post-1956. LeBlanc, who cut her political teeth as a native rights activist participating in the historic standoff at Wounded Knee, spearheaded the public access TV show Changing America, a precursor to the Independent Media Movement. Additionally, LeBlanc helped lead United For Peace & Justice, the largest peace coalition of the early 21st century. Other Communists, like Joe Sims and Jarvis Tyner, helped found and lead the Black Radical Congress (BRC), while still others held leadership positions in the United States Student Association (USSA), the Student Labor Action Project (SLAP), and Jobs With Justice (JWJ).

This is just a brief overview of the history Goldfield omits. An objective assessment of the CPUSA’s contributions during its 100-year history would no doubt include and expand upon the items above. Additionally, any history of the CPUSA, especially post-1956 (since this is contested historical terrain), must be considered in relation to the broader Left. Some of the New Left and New Communist Movements that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s—groups that have received considerable attention—could count their actual membership on one hand (at least according to FBI files), never mind their destructive sectarianism and ultra-left politics.

As others have argued, a “Red taboo” undoubtedly still exists in U.S. historiography. While I can appreciate Goldfield’s mostly sympathetic view of the early CPUSA, he and the Jacobin do their readers a disservice by perpetuating the dominant historical narrative, a narrative that does little to further the cause of socialism, a cause I believe we all share.

Tony Pecinovsky is the author of Let Them Tremble: Biographical Interventions Marking 100 Years of the Communist Party, USA, which can be purchased from International Publishers.

Images: Frank Wilkinson speaking to University of North Carolina Chapel Hill students, after being banned from speaking on the campus, March 2, 1966 (Flikr); Charlene Mitchell with Gus Hall, Mike Zagarell, PW Archives.

Join Now

Join Now