The world is always moving. What we call unchanging is just moving more slowly.

—Michel de Montaigne

Until now, philosophers have only understood the world; the point is to change it.

—Karl Marx

This is about dialectics—that is, about struggle, and hope, and revolution, and the whole process of making change in a changing world.

Dialectics is the logic of Marxism: the rules of thought, interpretation, and argumentation that are part of our scientific method. It’s a technique for finding meaningful patterns in the observable world.

When we think dialectically, we see the world as a set of interconnected processes of change and development. The opposite of dialectical thinking is metaphysical thinking, which sees the world as a collection of individual objects or concepts, each of which has to be understood on its own, in its unchanging essence, separately from everything else.

Why is this distinction so important? Why does dialectics matter?

What kind of heart does a revolutionary need?

The first answer is that the world is dialectical. Nothing is still, and nothing exists in isolation from its environment. If we want to understand that world, our understanding has to be based on interaction and change as well.

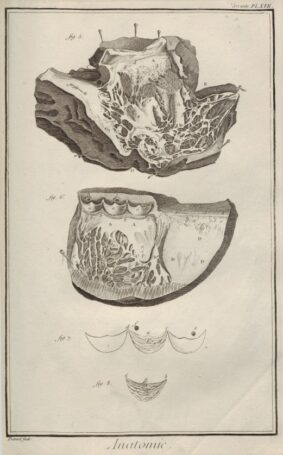

For example, this is an illustration of a dissected heart from the great French Encyclopédie of the eighteenth century, a monumental attempt to summarize all available knowledge in 28 volumes containing 71,818 articles and 3,129 engravings.

The explanation for the topmost image begins, “interior of the left ventricle. For this, a cut was made through the aorta and along the septum: only this cut can show the large valve…”

This is a metaphysical heart, in the Marxist sense: extracted from a body, cut and spread open, blood and blood vessels removed or pushed into the background as distractions, allowing the reader to concentrate on a single anatomical feature in a single position. This is typical of scientific thought in Europe in the eighteenth century, which focused heavily on breaking things down, isolating them, finding and classifying their basic components.

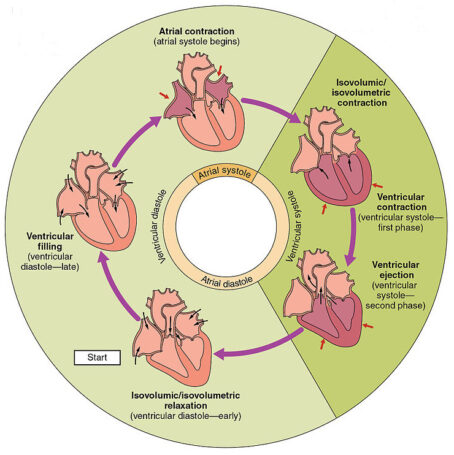

By contrast, we might call this a dialectical heart. The point isn’t to focus on a single piece of anatomy but on a physiological process. We see the organ in two different states (expanded in diastole to fill with blood, then contracted in systole to push oxygenated blood out into the body). This doesn’t give a full picture—for example, a real contraction doesn’t happen all at once—but it does show the heart in motion, in the context of the circulatory system.

By contrast, we might call this a dialectical heart. The point isn’t to focus on a single piece of anatomy but on a physiological process. We see the organ in two different states (expanded in diastole to fill with blood, then contracted in systole to push oxygenated blood out into the body). This doesn’t give a full picture—for example, a real contraction doesn’t happen all at once—but it does show the heart in motion, in the context of the circulatory system.

From a dialectical perspective, the world is made up of interconnected processes: in this case the circulation of the blood by the contraction of the heart muscle under electric current; the changes in pressure that move nutrients and waste products in and out of the bloodstream; and so on. Anatomical structures on their own, like we see in the engravings from the Encyclopédie, illustrate the characteristics of a single piece of the heart at a single moment in the process, but tell us very little about the process as a whole.

Why does this matter? Why is it so important that the heart of our politics be dialectical, a heart in motion rather than the stilled, dissected organ of the Encyclopédie?

Simply this: metaphysics is a trap. Metaphysical thinking claims to show us the inner truth of something, its unchanging essence. How often do we hear things like this?

- “Human nature is selfish, so socialism just can’t work…” (So stop fighting for change.)

- “The world isn’t fair, so stop whining and deal with it…” (By accepting injustice rather than struggling against it.)

- “The whole system is rotten, and attempts to work within it just give it legitimacy…” (So there’s nothing to do right now except call for revolution.)

Metaphysical thinking promises to strip away all the illusions, to get to the bottom of things and uncover the truth of what something really is. But at the end of the process, we find that we’ve dug a hole so deep we can’t see a way out or a path forward.

Where there is struggle, there is hope

Thinking dialectically—seeing things in motion and interaction and change—is how we avoid those traps. It reveals openings for struggle rather than dead ends and impossibilities; it orients and motivates rather than confusing and demobilizing us. One of the best illustrations of dialectics in action was provided by former CPUSA chair Henry Winston. Criticizing programs based on the necessity of armed revolution, he says:

Focusing on the gun in the future leads to frustration in the present. It carries the implication that any method short of the gun is inadequate or futile, amounting to no more than a holding operation until the real thing happens—merely a question of firing blanks until at long last reaching the point of “picking up the gun.”…

This view operates on the fatalistic notion that no matter what changes occur in the relationship of forces on a national and world scale, the working class and its allies will inevitably exhaust their capacity to prevent the ruling class from imposing armed struggle on the revolutionary process. (“The Crisis in the Black Panther Party,” Strategy for a Black Agenda)

Although Winnie doesn’t use the terms metaphysical and dialectical, that’s exactly the distinction he’s making.

Seen metaphysically, revolution is something cut and dried, like the drained and dissected heart from the Encyclopédie: everything stripped away to show the gun at the center. The process of transforming of society gets reduced to a single tactic; the “locomotive of history” is shrunk into a bullet. Winnie rejects that idea as fatalistic, a way of throwing up our hands and giving in, letting the ruling class impose its violence on our movement.

Revolution looks very different if we see it dialectically. It does not inevitably explode into violence; nor can it forcibly be compressed into a peaceful, electoral transfer of power. It is a process shaped by interacting and competing forces: by the antagonism between the capitalist class and the working class, by solidarity between workers and oppressed people, by developments in class consciousness, by levels of organization and mobilization, and by the pressures of capitalist crisis.

Looking dialectically, what we find is hope—not utopian optimism, but a thoughtful and disciplined confidence based on the understanding that the world changes through struggle, and that the working class has a uniquely powerful role in that struggle under capitalism. The revolution is ours. It will not play out some predetermined script. It will unfold and develop based on the struggles that we undertake and the unity we build here and now.

And isn’t that what we see all around us? The Trump regime and the extreme-right militia movement are trying to block off all avenues of non-violent democratic struggle, to force it along the path of violent confrontation, but they are failing because unity and organization and political understanding are growing. The revolution is ours, and our job is to prevent the capitalist class from imposing its violence on the process of transformation.

The science of struggle

As we approach the November elections, we face formidable challenges. The Trump-GOP regime has demonstrated that it will throw everything it has at the movement rising to meet the fascist threat—from imposing martial law in our cities to dismantling the postal service to prevent mail-in voting. At the same time, a vast people’s movement has arisen. For that movement, defeating Trump is simply one step on the road to a much more fundamental transformation of society along democratic and even socialist lines.

As the democratic uprising intensifies and the Trump regime escalates its fascist rhetoric and tactics, how have the “moderates” in the leadership of the Democratic Party responded?

Backing New Deal–style relief one minute and taking a hard-line stand against Medicare for All the next; proclaiming that Black lives matter enough to paint the street, but not enough to defund police; blasting Trump’s “America First” nationalism while joining with Republicans in neoconservative saber rattling on China; backing a substantial police reform bill, but embracing candidates whose political history gives little evidence of willingness to stand up to police unions. Looking to them for leadership will make your head spin, at best, and can even result in a debilitating case of political whiplash.

Our ability to move forward depends on how we interpret the behavior of these anti-Trump forces in the capitalist class.

If we try to pin them down like the heart from the Encyclopédie, to immobilize and dissect their behavior so it’s easier to examine, all we see is hypocrisy and betrayal. We see a democratic façade over the same old capitalist brutality; a superficial embrace of a people’s agenda covering a profound aversion to empowering the people. But this is what metaphysics always shows us: a world split into appearance vs. reality, deceptive surface vs. hidden truth. It promises to strip away the illusions and reveal the unchanging essence of the object of study.

That sounds very Marxist, all demystification and “relentless criticism of everything that exists.” But is it?

Marxism is dialectical in its critique. The heart of things is in motion, and getting to the heart of things means understanding that motion, looking at the interplay of forces that make up whatever phenomenon we’re looking at. Take Marx’s analysis of capital, for example. In its bourgeois definition, capital is just money for investment, money poured back into making a profit. But Marx reveals it as a set of unequal social relations through which wealth created by workers is appropriated by property owners. His demystification of capital moves from the metaphysical (capital as a thing) to the dialectical (capital as a set of relations and processes, rife with contradictions and undermined by its own growth).

So what do we see when we look dialectically at the liberal-democratic wing of the ruling class—titans like Gates, Bezos, Soros, and Bloomberg—and institutions like the Democratic National Committee? Not carefully curated deception, but inconsistency and desperate vacillation: a party pulled back and forth, contorted into the most nonsensical positions by contradictory interests.

Their political power depends on an electoral coalition that includes organized labor, women, people of color, and other oppressed groups (including, increasingly, in their roster of officeholders). Keeping that coalition requires concessions that limit their power over labor and their ability to extract profits. At the same time, the power of the extreme right applies an opposing force, pulling them via their pocketbooks toward violent and anti-democratic solutions, especially in times of crisis. Their platform, legislative priorities, and electoral strategy reflect the interaction of those forces.

In other words, the liberal-democratic wing of the ruling class has lost, or is well on the way to losing, the ability to impose its own priorities on the struggle against fascism. The results of that struggle will be decided by the contest between the working class and people’s movement on the one hand, and the increasingly open and violent fascist reaction on the other. The immediate task is not to discredit or sideline the liberal bourgeoisie, any more than it is to follow and celebrate them. Instead, it is to weaken the extreme right and strengthen our movement to the point where “moderate” opportunists can no longer use the threat of Trump and the Republican Party as cover—where, in other words, a “bipartisan compromise” is between Pelosi and the Squad rather than Pelosi and McConnell. (This is what we refer to as “changing the balance of forces,” and it is already well underway.)

Here again, dialectical thinking reveals avenues of struggle, possibilities of change, and strategic and tactical priorities that connect our current struggles to socialist revolution and the transformation of society when it is freed from the shackles of capitalism.

That’s why dialectics is worth it, at least for me: as a source of clarity, and therefore hope. It enables us to think scientifically about development and transformation. It nourishes our revolutionary hope for a better world by grounding it in an understanding of how to get there.

Assessing the relationship between democratic and socialist revolutions, Lenin said, “The first develops into the second. The second, in passing, solves the problems of the first. The second consolidates the work of the first. Struggle, and struggle alone, decides how far the second succeeds in outgrowing the first.”

We might take that as the whole philosophy—the heart, perhaps?—of dialectics, in just four words: struggle, and struggle alone.

Images: (top) Becker1999, Creative Commons (BY 2.0); “dialectical heart,” Wikipedia.

Join Now

Join Now