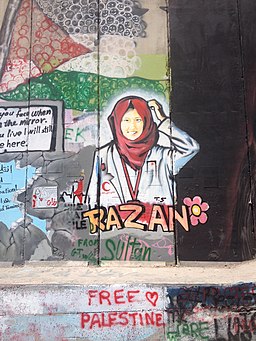

She was Razan al-Najjar or Rouzan Ashraf Abdul Qadir al-Najjar. She was only twenty years old. Palestinian. Eldest of a family of six in the Gaza village of Khuza’a. A nurse/paramedic. Idealistic, fearless, passionate for her homeland.

And murdered by an Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) sniper on June 1, 2018, during peaceful protests against the 11-year-old Israeli blockade of Gaza.

“Why kill her? She was an angel of mercy,” cried Ashraf al-Najjar, her shattered father. She is now al-istishhadiyyat — a martyred young woman.

Her heroic role in the ongoing protests was to treat the wounded. Razan was trained as a paramedic at Nasser Hospital in nearby Khan Younis. At protests, medics were “easily identifiable” and “did not pose any threat to the Israelis.” They practiced “fine-tuned strategies,” wearing white jackets with reflective high-visibility stripes, moving slowly forward in teams, arms and hands raised high, Razan even wearing surgical gloves as a form of identification.

Her family, living under blockade, could not send her to college. According to the New York Times, “knowing she couldn’t afford college dejected her,” and her goal was “making nursing school affordable.” She “hung around emergency rooms, running errands, observing surgery,” and purchased medical supplies with her own money, even selling a gold ring for funds.

Razan belonged to the Palestinian Medical Relief Society, working 13-hour shifts from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. without pay. When the health ministry required volunteer medics to take a written exam, Ms. Najjar scored 91, the highest in her group of 200. “She was given an identification card, lab coat, and white-and-pink paramedic’s vest. She wore them like armor.” After the protests ended, she was determined to “ace the college-admission tests . . . and find her way to nursing school.”

Razan belonged to the Palestinian Medical Relief Society, working 13-hour shifts from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. without pay. When the health ministry required volunteer medics to take a written exam, Ms. Najjar scored 91, the highest in her group of 200. “She was given an identification card, lab coat, and white-and-pink paramedic’s vest. She wore them like armor.” After the protests ended, she was determined to “ace the college-admission tests . . . and find her way to nursing school.”

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has asserted that “Israeli snipers intentionally shot health workers” that day. The Israeli human rights group B’Tselem clarified that Razan was shot “deliberately” by an Israeli soldier “aiming directly at her . . . despite the fact that she posed no danger to him or anyone else and was wearing a medical uniform.” A UN official called the killing “particularly reprehensible,” noting that “health personnel and ambulances” were targeted by Israel. The New York Times reported that the bullet that killed Razan had ricocheted and fragmented . . . into a crowd that included white-coated medics in plain view” and that the killing was “reckless at best, and possibly a war crime.”

According to Al Jazeera, Razan seems to have been slain by a “butterfly bullet,” which “explodes upon impact, pulverizing tissue, arteries, and bone and causing severe internal injuries.” Mohammed al-Hissi, Director of a Red Crescent Emergency Medical Team, said: “This is a war crime against health workers and a violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention which gives medics the right to offer their assistance.” A UN Security Council Resolution accusing Israel of using “excessive, disproportionate, and indiscriminate force” was vetoed by Israel’s enabler and partner in capitalist crimes, the U.S.

Needing no prompt to murder, Israel “considers members of Hamas fair game whether they are armed or not, an interpretation of international law not universally accepted.” And deliberately shooting a medic is certainly a war crime. The International Criminal Court announced on March 3 that it will investigate Israeli crimes within Palestinian territories.

Razan’s mother, Sabreen, described her daughter as “a mother to the protestors.” She added that “her only weapon was her medical vest . . . a vest Razan thought would protect her.” Sabreen held high the medical ID Razan wore when killed: “Is this the ID of a terrorist?” Ashraf, her father, held aloft her bloodied medical vest: “This is Razan’s weapon.”

“Charismatic and committed,” Razan was “a feminist, by Gaza standards, shattering traditional gender rules” to “inspire other women to become medics, despite social conventions in this deeply conservative Muslim territory that reserve dangerous work for men.” She protested not only the Israeli occupation but also Palestinian patriarchy:

Women are often judged, but society has to accept us. If they don’t want to accept us by choice, they will be forced to accept us. Because we have more strength than any man. The strength that I showed the first day of the protests, I dare you to find it in any man.

For the IDF Razan is “a nightmare of a victim — a photogenic symbol of nationhood, youth, and compassion.” On the day of her murder she told a reporter: “I love working here with everyone.” Rami Abu Jazzar, a fellow medic shot in the left knee on the same day, said, “She smiled all day. It was a beautiful day working with her.”

To the young male protestors “she seemed to appear beside them almost as fast as they fell,” even though “shrapnel pelted her legs, a flaming tire burned her, a tear-gas grenade fractured her arm. She cut off her cast the same day and went back to the protest.”

But Razan’s bravado “became alloyed with increasingly frequent allusions to her possible demise,” as “she believed the IDF was targeting her months before her death” and noted that “Israeli soldiers had shot directly at her multiple times in a warning not to tend to the wounded in the protests.”

Zionists claim existential fear of annihilation: The Israelis viewed her as a “part of a violent protest aimed at destroying their country, to which lethal force is a legitimate response.” But author Norman G. Finkelstein reveals how Israel uses the Holocaust as dramatic justification for crimes against the Palestinian people:

The Holocaust has proven to be an indispensable ideological weapon. Through its deployment, one of the world’s most formidable military powers, with a horrendous human rights record, has cast itself as a “victim” state. . . . Nazi genocide . . . has been used to justify criminal policies of the Israeli state and U.S. support for these policies.

Martyrdom can be attractive in the face of despair. According to The Making of a Human Bomb (Abufarha), a book about the psychology of Palestinian suicide bombers, martyrdom becomes

a preferred form of living over the crippled present life. Death becomes a form of living that is more meaningful than life of the physical sort so that the martyr is alive in spite of death. Here is a consciousness of the [martyr’s] broader ability . . . to shape . . . national, regional, and potentially global levels, an ability that ‘begins’ with the dying of the body. Thus the conceptual space that the martyr’s life occupies is much wider than the physical and social space that the person occupies in life.

A politically meaningful death can be appealing when military efforts have failed to achieve liberation. Young Razan lived through not only the violence of occupation and economic suffocation but also three Israeli wars against her people in Gaza. And the so-called Middle East peace process, characterized largely by costly Palestinian concessions and unreasonable Israeli demands, also failed (see The International Diplomacy of Israel’s Founders: Deception at the United Nations in the Quest for Palestine, by John Quigley). Despair is the most readily available commodity in Gaza, the world’s largest prison.

Did Razan believe she could further the Palestinian cause better as al-istishhadiyyaat — a martyred young woman? We cannot know if she embraced such selflessness — and such despair. Sabreen, her mother said, “While many in Gaza speak of death as preferable to the here-and-now, Razan clung to life. She never wanted to be a martyr.”

But fellow protestors described her as “the slowest to retreat” with a “readiness to place herself in harm’s way”; while “others cowered . . . Not Ms. Najjar.” She was “the first to those in trouble, the last to safety,” and “she wanted to always be at the fence, to be a daughter of men” — a cultural expression denoting a woman driven by a strong sense of national identity. Eslam Okal, a trauma nurse, bluntly said, “She was reckless . . . I told her ‘Your first priority is safety’. We had many arguments over this. But her bravery won out.”

Razan told the New York Times: “We — without weapons — we can do anything. I am protected by my vest. God is with me. I am not afraid.” She later wrote, “They said to me, ‘Bend a little, as the bullet is on its way to you,’ so I said to them, ‘the bullet chose me because I do not know how to bend, so why should I change my way?’” A colleague recalls: “I said I hoped we wouldn’t get hit. To which she replied, ‘So be it! We die as friends.’”

Razan told the New York Times: “We — without weapons — we can do anything. I am protected by my vest. God is with me. I am not afraid.” She later wrote, “They said to me, ‘Bend a little, as the bullet is on its way to you,’ so I said to them, ‘the bullet chose me because I do not know how to bend, so why should I change my way?’” A colleague recalls: “I said I hoped we wouldn’t get hit. To which she replied, ‘So be it! We die as friends.’”

Her mother spoke of the day Razan died: “She stood up and smiled at me, saying she was heading out to the protest. . . . In the blink of an eye, she was out the door. I ran to the balcony to watch her but she had already made her way to the end of the street . . . She flew like a bird in front of me.”

It is easy to believe that Razan is in heaven. She was brave, virtuous, selfless, idealistic, and devoted to the liberation of her people and homeland. A poem eulogizes her by observing that, with her presence, “heaven is now complete.”

Zionist Israel, however, is in political and moral hell, forever faced with the daunting task of justifying a nation built on theft, ethnic cleansing, and outright murder. Desperate hasbara and chutzpah cannot conceal the truth: Israel “could not fully supplant the country’s original population, which is what would have been necessary for the ultimate triumph of Zionism.” As Rashid Khalidi has written,

For all its might, its nuclear weapons, and its alliance with the United States, today the Jewish state is at least as contested globally as it was at any time in the past. The Palestinians’ resistance, their persistence, and their challenge to Israel’s ambitions are among the most striking phenomena of the current era.

Palestine is at the heart of the global struggle against capitalism. And angelic Razan al-Najjar is an inspiration to the oppressed and exploited of this world, with the sumud (steadfastness) of Palestinian fida’iyeen (freedom fighters) inviting comrades everywhere to proclaim, We Are All Palestinians!

Sources

Linah Alsaafin and Maram Humaid, “In Gaza, Grief and Pain for Slain ‘Angel of Mercy’ Paramedic,” Al Jazeera, June 2, 2018.

B’Tselem, “Israeli Soldiers Deliberately and Fatally Shot Palestinian Paramedic Rozan a-Najar in the Gaza Strip,” July 17, 2018.

David M. Halbfinger, “A Day, A Life: When a Medic Was Killed in Gaza, Was It an Accident?,” New York Times, Dec. 30, 2018.

“Rouzan al-Najjar,” Wikipedia.

Ian Lee and Dominique van Heerden, “’Her Only Weapon Was Her Medical Vest’: Palestinians Mourn Death of Nurse Killed by Israeli Forces,” CNN, June 3, 2018.

Nasser Abufarha, The Making of a Human Bomb (London: Duke University Press, 2009).

Norman G. Finkelstein, The Holocaust Industry (New York: Verso, 2000).

Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years War on Palestine (New York: Henry Holt, 2020).

Images: top, two young women in London protesting Israeli violence in Gaza, Alisdare Hickson (CC BY-SA 2.0); Razan al-Najjar, Hassan Shoapp (Wikipedia, fair use); mural, Wikipedia (CCO 1.0 Universal Public Domain).

Join Now

Join Now