“Happy May Day 2023, Chicago! May we always stand in solidarity with workers everywhere to ensure fair wages, safe working conditions, and the right to organize.

“Never forget: the power of the people is what built this city and makes Chicago strong.”

So tweeted Chicago mayor-elect Brandon Johnson, a labor leader, Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) organizer, and former Chicago Federation of Labor member. Johnson, also a Cook County Commissioner, was elected mayor on April 4, defeating Paul Vallas.

On May 15, Johnson and 50 aldermen will take office. Among them are six DSA members, an Indivisible leader, LGBTQ activists, a union organizer, and other progressives, making this city council the most diverse and one of the most progressive in Chicago’s history.

On May 2, sixty elected officials — including many grassroots frontline fighters for criminal justice reform, police reform, and gun safety — took office in 22 newly created police district councils. The Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability is a new, advanced, grassroots democratic body and is a step toward community control of the police.

This reform also includes a body that will interview and propose a list of three candidates for a new police superintendent that Johnson will choose from.

In 2024, Chicago voters will begin electing a representative School Board in another democratic advance.

Johnson’s victory and these significant democratic reforms weren’t possible without dramatic shifts in public opinion and the growth of a united mass democratic movement, of which Johnson was a leader. The growing clout of people-centered politics and its turn to electoral politics makes Chicago more democratic and representative.

Johnson is not alone among newly elected progressive mayors. Broad-based, diverse, multi-racial people’s coalitions have helped elect a wave of new progressive mayors and elected officials in the last few years, including Johnson, Karen Bass in Los Angeles, Michelle Wu in Boston, Tishaura Jones in St. Louis, Ras Baraka in Newark, and Chokwe Antar Lumumba in Jackson, MS. Helen Gym could join this group if she is elected mayor of Philadelphia on May 16.

There are undoubtedly others, and their election impacts governing, public policy, and grassroots democracy. These new officials are largely activists and leaders of mass movements, helping transform the very bodies they are elected to.

Mass democratic coalitions, instrumental to these victories, are now in a position to play an essential role in governing and addressing the deep crises cities face and mobilizing the public behind a people’s agenda, including in Chicago.

These victories are a vital part of the bigger picture of victories by working-class and people’s movements organizing to elect Democratic-dominated state legislatures and progressive-oriented governors — including Illinois Governor Pritzker, and fighting to pass legislation and constitutional amendments that expand voting, workers’, reproductive, and LGBTQ rights, and that advance social and environmentally sustainable policies.

Johnson’s victory over Vallas, by 52 to 48%, was a vote of hope over fear and an embrace of Johnson’s vision of a more equitable, people-centered city. Most voters rejected Vallas’s “tough on crime” fear-mongering and the threat of a return to the old Chicago politics: racial division, machine-autocratic rule, corporate plunder of public assets, and notorious corruption resulting in vast racial and economic inequality. The old politics distorted Chicago’s urban development with luxury housing downtown and increasingly unaffordable housing everywhere else.

Johnson’s victory represents mass embrace of broad progressive politics, a turn toward the ballot box, and decades of grassroots organizing against corporate domination of politics, systemic racism, inequality, and monopoly capital’s plunder of public assets.

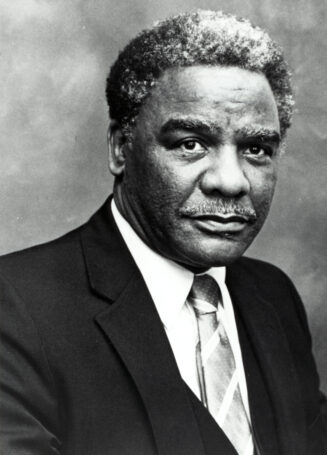

Reminiscent of Washington coalition

The victory is reminiscent of the grassroots electoral coalition that elected Mayor Harold Washington in 1983, and again in 1987 before his untimely death — but on a more advanced ideological, political, and organizational level.

The victory is reminiscent of the grassroots electoral coalition that elected Mayor Harold Washington in 1983, and again in 1987 before his untimely death — but on a more advanced ideological, political, and organizational level.

By comparison, Washington won in 1983 with 93% of the African American vote, only 9% of white voters, and 9% of Latino voters. Forty years later, Johnson prevailed with 80% of African American voters, 39% of white voters, and 49% of Latino voters. Johnson won 29 of 50 wards, including 17 predominately African American wards and 13 predominately white and Latino wards, including six predominately white liberal Northside wards.

Chicago remains one of the most segregated cities in the U.S. African Americans, Latinos, and whites are nearly evenly split as a proportion of the city’s population, and there is a growing Asian American population, but these communities are largely sectioned off from one another, living, working, and going to school in geographically separate areas. But the election also shows how much has changed politically.

Finally, Johnson was the candidate of the youth, who increased their turnout by over 30,000 votes from the February 28 general election to the April 4 runoff. Fifty-nine percent of voters were 44 years old and under, and the 18-24 vote surged by 30%. The Johnson campaign consciously targeted young voters with outreach through social media and other means.

Besides youth, the Johnson coalition included the CTU, SEIU, AFSCME, and other unions; the Working Families Party coalition; Indivisible; social, environmental, and criminal justice reform and gun safety organizations; progressive independent and Democratic Party ward organizations; African American churches; LGBTQ organizations, and elected officials across the board. All these forces were involved in a vigorous get-out-the-vote mobilization.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, who visited twice during the election, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and Rep. Chuy Garcia, who finished 4th in the general election, endorsed Johnson. This helped bring in support from voters who were progressive, but did not yet know about Johnson and his record. Garcia’s support was especially critical in mobilizing Latino voters on the Southwest side, where his robust political organization shattered the Democratic Party machine and elected many young Latinos to office.

On the other hand, a cabal of right-wing billionaires backed Vallas, along with leading center forces in the Democratic Party, including Rahm Emanuel, Sen. Dick Durbin, former Secretary of State Jesse White, former U.S. representative Bobby Rush, and other elected officials (Gov. J.B. Pritzker remained neutral), Democratic machine remnants, some building trades unions, the fascist-led Fraternal Order of Police, and the Illinois Republican Party.

Some center-oriented Democratic Party officials supported Vallas to undercut the growing clout of the progressive coalition backing Johnson. Others feared voter backlash over “defund the police” remarks Johnson made during the height of the George Floyd protests, which he later walked back.

In the end, voters were more concerned with Vallas’s admission of being closer to a Republican than a Democrat, his anti-abortion stance, his support for school privatization, and policies that left a trail of destruction in Chicago, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Bridgeport, CT, his thinly veiled racist appeal to “take back our city,” and his support from the Fraternal Order of Police.

Two decisive issues in the election are worth highlighting. They say much about shifting sentiments and grassroots political organizing here.

Public safety was the top election concern. But most voters rejected Vallas’s “tough on crime” fear appeal and his agenda to add more cops and association with the fascist-led FOP. Instead, voters embraced Johnson’s “constitutional policing” agenda, a thoughtful and wholistic approach to treating the “root causes” of crime and violence, creating jobs and opportunities for youth, especially in the most marginalized neighborhoods, a “treatment not trauma” strategy to fund mental health services including counselors, social workers, and affordable housing and education.

Want something done

People want something done about crime and violence. Still, most understand that more cops, aggressive policing, and “stop-and-frisk” policies aren’t effective, and instead lead to significant community-police tensions, police brutality, and murders — especially of unarmed African American and Latino young men. Besides, Chicago is already one of the most policed cities in the country.

And the city was rocked by the George Floyd demonstrations, continuing decades of protests against the notorious brutality, lethality, and racism of both the Chicago Police Department and of the criminal justice system that falsely convicted many people, some serving decades-long sentences. The CPD is under a Federal Consent Decree mandating systemic changes.

Out of these movements, led by the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, other groups, and victims and survivors of police brutality, came the demand for civilian control of the police. This movement allied with key unions — including the CTU, and elected officials to win the historic city council legislation establishing police district councils. It introduced an alternative vision for public safety into the public discourse. Johnson embraced this movement.

The second major issue is the defense of public education. With Vallas in charge, the Daley administration imposed a new education policy in the 1990s, including top-down management, an appointed school board dominated by corporate interests, attacks and restrictions on the CTU, privatization, and charter schools. The policies were guided by so-called “school accountability,” which meant punishing teachers, students, and entire schools that had low test scores with closure. It meant looting the school system by diverting public funding to wealthy real estate interests. Mayor Rahm Emanuel also championed these policies.

But support for these policies, once embraced by the Democratic Party leadership, has eroded over the past 20 years in Chicago and nationally. The vigorous fightback by the CTU after a leadership change in 2010, and by parents and students, led to the 2012 and 2019 CTU strikes widely supported by the public. The CTU-led coalition impacted education policies, and ultimately, the state legislature passed legislation establishing an elected school board. Johnson was a leader of this movement.

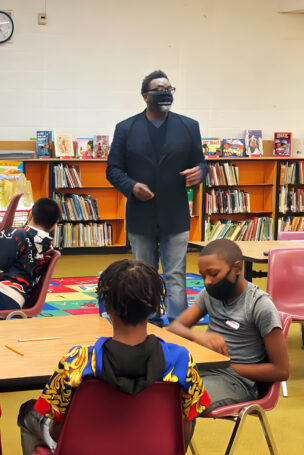

Johnson campaigned on an education agenda, advocated by the CTU, for a moratorium on school closures, full and equitable funding of schools, and hiring more teachers and staff, including social workers, nurses, librarians, and counselors. The plan calls for more significant investment in students and communities, especially historically marginalized communities, and eliminating standardized testing.

Johnson campaigned on an education agenda, advocated by the CTU, for a moratorium on school closures, full and equitable funding of schools, and hiring more teachers and staff, including social workers, nurses, librarians, and counselors. The plan calls for more significant investment in students and communities, especially historically marginalized communities, and eliminating standardized testing.

The CTU will be a partner, not an adversary, in the new administration, but this new relationship, along with other coalition partners, will be tested during times of crisis.

The big challenge awaiting Johnson and the democratic people’s coalition instrumental in electing him is governing effectively despite lacking resources, resistance from machine remnants and corporate and wealthy interests, and sabotaging public safety by the FOP. Alternative funding sources, like progressive taxation and reallocating resources in Chicago, the state, and nationally are needed, along with reelecting President Biden and Democratic Congressional and state legislative majorities.

Johnson is taking steps to ensure his administration is inclusive and collaborative, beginning with reaching out to all civic sectors and seeking community input into the administration’s priorities.

The administration’s transition team is composed of leaders of SEIU, AFSCME, and WFP with liaisons to business and the state legislature. Barbara Ransby, a UIC professor, feminist, and racial justice activist, and Emma Tai, director of the WFP, co-chair the transition team.

Eleven issue subcommittees, involving 400 leading activists and civic leaders, are developing policies ranging from education to labor to policing to economic development and equity in order to shape and guide the administration’s work.

Johnson is staffing posts by placing experienced administrators and working collaboratively with the governor, state legislature, and other Democratic Party elected officials. But the hard work lies ahead.

Huge problems await the new mayor, including a lack of federal, state, and local funding, massive poverty, gun violence, a homelessness crisis, deep structural inequality, and the need to provide immediate care for thousands of migrants being bussed to Chicago by Texas Governor Greg Abbott. In addition, there will be fierce resistance from right-wing, corporate forces, from machine remnants, and from the FOP leadership.

But the moment holds the potential to be transformative, reshaping urban social policy and setting Chicago on a different, more inclusive, equitable, and democratic trajectory. And if the alliance between the Johnson administration and the mass democratic movements remains unified, successfully navigates turbulent waters, and Johnson’s narrow victory turns into a more significant governing majority, good things are possible.

Images: Chicago Teachers on Strike by John W. Iwanski (CC BY-NC 2.0) / ECPS march by CAARPR (Facebook) / Brandon Johnson and CTUs oldest delegate Bea Lumpkin embrace at the Local 1’s House of Delegates meeting by CTU (Twitter); Harold Washington (public domain); CTU with Brandon Johnson gathering in defense of reproductive rights by CTU (Twitter); Brandon Johnson in the classroom by Brandon Johnson (Twitter)

Join Now

Join Now