“The principal content of the activity of our Party organization, the focus of this activity, should be work of political agitation, connected throughout Russia, illuminating all aspects of life, and conducted among the broadest possible strata of the masses. But this work is unthinkable in present-day Russia without an all-Russia newspaper. The organization, which will form around this newspaper, will be ready for everything”

In 1902, Vladimir Lenin wrote What is to be Done, his text on the political goals and tactics for the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. In this text, he famously goes into the need to have dedicated professional revolutionaries to organize party work, as well as the role of the party of the proletariat (i.e. working class) as a vanguard (or leading force) within the movement. All this is important, but What is to be Done is also essential in Lenin’s emphasis on the press and the party newspaper. How Lenin specifically conceived of the newspaper as an organ of the party apparatus is essential in understanding our own political work within the Communist Party today.

Russia in Lenin’s time

To understand the importance of Lenin’s conception of the party newspaper, we have to look at the conditions of Russia in the early 20th Century. In the text, Lenin characterizes three periods in the development of Social Democracy in Russia, stating the initial stage was from 1884 to 1894. “This was the period of the rise and consolidation of the theory and programme of Social-Democracy,” he wrote. This was social democracy in an embryonic and uncoordinated form, detached from a concrete movement and without a developed, militant political party.

The second period was from 1894–98. In this period, “Social-Democracy appeared on the scene as a social movement, as the upsurge of the masses of the people, as a political party. …This was also the period where the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class was formed, before merging into the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party.”

The second period was from 1894–98. In this period, “Social-Democracy appeared on the scene as a social movement, as the upsurge of the masses of the people, as a political party. …This was also the period where the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class was formed, before merging into the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party.”

In 1902, the 3rd period was occurring as Lenin was writing What is to Be Done. This period was characterized as one of ‘Disunity, dissolution, and vacillation.’ But as Lenin states, this disunity was not on the part of the workers, who were eager to take action, but on the part of the leaders of social-democracy themselves. “It was only the leaders who wandered about separately and drew back,” he wrote then. “The movement itself continued to grow, and it advanced with enormous strides.” This new stage saw the proletarian struggle spread to new strata of workers, as an upsurge of activity was experienced.

A year prior, Lenin had written Where to Begin, a text which combines the immediate needs of a revolutionary organization with the necessity to form an all Russian political newspaper. In the text, he stated that the aim of this newspaper was to build the forces necessary to wage a decisive struggle against Tsarism, and to “Unite all forces and guide the movement in actual practice, and not in name alone.”

Combining political and economic struggle

“There is no other way of training strong political organizations except through the medium of an all-Russia newspaper.”

At this stage in the development of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) it was necessary to have a party newspaper. But why was this? In 1902, the RSDLP had contested views on the next steps forward. At this time, there were other working-class movements, with working-class newspapers, all with contesting attitudes of the correct path for change. For instance, the “economists” such as Krichevsky and Martynov saw Lenin’s theory and political program as disconnected from the militant union struggle. Krichevsky once wrote, “The most serious blunder Iskra [the newspaper of the RSDLP] committed in this connection” is that they “convert theory into a lifeless doctrine by isolating it from practice.” In 1901, Lenin’s initial recommendation to build a militant party under the coordination of the newspaper was challenged by a number of publications, including Rabyche Dyelo (organ of the Union of Russian Social Democrats Abroad) and others.

As the spontaneous union movement was building within the factories (often based upon the English trade union struggle), “economists” such as Martynov and Bernstein saw party structure and theory as disconnected from the direct and spontaneous worker struggle. They believed the program did not correspond to the concrete demands in the factories or in the economic fight for wages in specific trades. These “economists” viewed theory as secondary because they thought it could isolate workers. As one newspaper, Rybocheye Mysl, (representing the interests of this economic movement) said, “We must concentrate, not on the ‘cream’ of the workers, but on the ‘average’ mass worker.” In fact, in What is To Be Done, the economists said plainly they are fighting, not for the sake of some future generation, but for their own immediate aims and those of their children.

This economic struggle would later be taken up as a theoretical line that argued, “Politics always obediently follows economics,” and for the need to “Give the economic struggle itself a political character,” which Lenin disagreed with. But Lenin did not disagree with using the economic struggle as one of the strategies for the overall political struggle, he disagreed with limiting this fight only to the economic, trade unionist, struggle. As Lenin wrote, “Revolutionary Social-Democracy has always included the struggle for reforms as part of its activities,” especially reforms that would help the fight against the Tsarist government in Russia. It was a matter of using the economic struggle as a form of agitation in order to present “not only demands for all sorts of measures, but also the demand (and primarily) that [the government] cease to be an autocratic government.” Lenin and the RSDLP wanted to incorporate and build every discontent of civic life into a tool to overthrow the Tsar.

The role of the revolutionary newspaper

For Lenin, establishing an all-Russian newspaper was the first concrete step to concentrate all party activity around a common effort, and to frame Tsarist attacks within the political struggle. Naturally, this paper had to act as an organ or voice of the party, and a centerpiece of the party’s common work. Every struggle in the country was an opportunity to develop mass political movements and build the base of this movement. It was with this perspective that Lenin conceived of party literature and the Communist press.

As Lenin states in What Is to be Done, this agitation could not come from simply explaining the discontents to the workers, it had to take on the form of agitation around every example of civic life.

“It is not enough to explain to the workers that they are politically oppressed (any more than it is to explain to them that their interests are antagonistic to the interests of the employers). Agitation must be conducted with regard to every concrete example of this oppression (as we have begun to carry on agitation round concrete examples of economic oppression). Inasmuch as this oppression affects the most diverse classes of society, inasmuch as it manifests itself in the most varied spheres of life and activity — vocational, civic, personal, family, religious, scientific, etc., etc. — is it not evident that we shall not be fulfilling our task of developing the political consciousness of the workers if we do not undertake the organisation of the political exposure of the autocracy in all its aspects? In order to carry on agitation round concrete instances of oppression, these instances must be exposed (as it is necessary to expose factory abuses in order to carry on economic agitation).”

For the RSDLP, it was possible to do this political work through the all-Russian newspaper. In order to connect every worker and every facet of working-class life, this struggle would have to expand outside of abuses in the factory and incorporate all aspects of civic life. The press would be a centralized voice for the party to expose the Tsarist atrocities within the workers’ movement.

Engaging in the battle of ideas

Lenin argued that the newspaper should serve as the political foundation around which all party work would be centralized. The party used the newspaper as a way to direct spontaneous and embryonic consciousness toward political and class consciousness. The newspaper could exist to document the atrocities that were occuring throughout the Tsarist empire, but also take these severe instances of oppression and connect the struggle against them to the RSDLP political program and party.

Lenin also pointed out that while many of his contemporaries only recognized two forms of struggle (political and economic), Friedrich Engels recognized three, “placing the theoretical struggle on a par with the first two.” In his work The Peasant War in Germany, Engels wrote that the German workers’ direct relationship with theory — specifically German Philosophy, and, in particular, Hegel, which inspired the creation of scientific socialism — gave them an advantage in their struggle, which other European workers did not have.

“Without a sense of theory among the workers,” he wrote, “this scientific socialism would never have entered their flesh and blood as much as is the case. For the first time since a workers’ movement has existed, the struggle is being conducted pursuant to its three sides – the theoretical, the political, and the practical-economic.”

The party newspaper is connected to this theoretical struggle. The party newspaper elevated the political struggle both as an organizational tool for the party, and as an agitational tool among the masses.

The Bolshevik newspapers’ reach and influence

RSDLP’s newspapers played a significant role in the struggle to end Tsarism. This was true despite incredible suppression and raids from the Tsarist government, in addition to attacks from the bourgeois press, which had much more resources available and a wider readership. In fact, the book Lenin and the Bourgeois press states that:

“In 1905, for example, the sum total of legal Bolshevik publications, despite hard-won democratic liberties, never rose even to ten. What is more, these only came out for a short time, at different times, and were often simply replacing one another. Together with short-lived and irregular illegal periodicals, they amounted to no more than about thirty even in 1905, the year of revolution. And yet, the total number of papers and journals in Russia stood at approximately 1,350. In titles alone, the non-Marxist press exceeded the Marxist press almost 45 times! And if one bears in mind that the entire government, bourgeois-monarchist and bourgeois-liberal press, and even, in part, the bourgeois-democratic press, was never subject to any repression from the authorities and therefore came out without interruption, and possessed a whole army of experienced journalists, then one can see that this preponderance was even more impressive.”

These Marxist publications were received with increasing popularity from citizens, from illegal Bolshevik newspapers to legal journals and proclamations. Every copy of the illegal press was circulated from hand to hand and was read by dozens and sometimes even hundreds of people. That is why the influence of the Bolshevik and bourgeois press could not be measured in terms of number of registered readers during the revolution of 1905. In referring to the importance of having the newspaper as a tool for propagandizing the class struggle to workers, Lenin wrote, “How much broader and deeper are now the sections of the people willing to read the illegal underground press, and to learn from it ‘how to live and how to die’, to use the expression of a worker who sent a letter to Iskra.”

The Communist Party USA and our newspaper

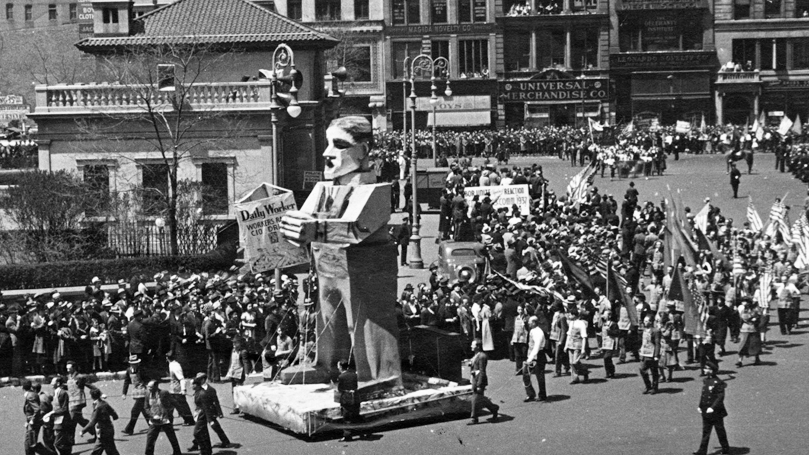

Our own party’s literature has been a tool to strengthen working-class movements and further the cause of socialism. In a section of his book Hammer and Hoe, D.G. Kelley describes how, in 1934, Alabama sharecroppers formed a cadre around reading the Daily Worker. These workers interpreted Communism through their own experiences and used the Communist Party’s literature as a guide in the struggle against exploitation and for Black liberation.

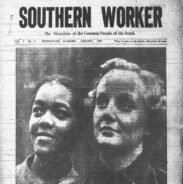

“Activists found creative ways to overcome their inability to read and write, which included having Party material read to them. The Party formed study groups that read works in pamphlet form, ranging from James Allen’s Negro Liberation and Lenin’s What Is to Be Done to Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto. By mid-1934, the Bessemer section of the Party designated one half-hour of each meeting for study-fifteen minutes of reading aloud and fifteen minutes devoted to discussion. Local leaders made literate members responsible for tutoring their illiterate comrades by establishing partners who met on a regular basis and read Communist tabloids together. Publications such as the Southern Worker, the Daily Worker, Working Woman, the Labor Defender, the Young Worker, and the Liberator were also important sources of information for black Communists.”

“Activists found creative ways to overcome their inability to read and write, which included having Party material read to them. The Party formed study groups that read works in pamphlet form, ranging from James Allen’s Negro Liberation and Lenin’s What Is to Be Done to Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto. By mid-1934, the Bessemer section of the Party designated one half-hour of each meeting for study-fifteen minutes of reading aloud and fifteen minutes devoted to discussion. Local leaders made literate members responsible for tutoring their illiterate comrades by establishing partners who met on a regular basis and read Communist tabloids together. Publications such as the Southern Worker, the Daily Worker, Working Woman, the Labor Defender, the Young Worker, and the Liberator were also important sources of information for black Communists.”

In the cases of both Iskra in Russia in the early 20th century (and Pravda after 1912), and the Daily Worker in the U.S. in 1934, both newspapers occupied roles as a tool for initiating political activity. Our party agitated based on the struggles featured in the Daily Worker, The Communist, and the Southern Worker, using the publications to promote a concrete party program and organize around a progressive political agenda. It was in these newspapers that new articles on the political struggle within their respective countries could be shown and used as an agitational and organizational tool to build mass consciousness. Lenin spoke of this essential nature of the party press as agitator in a 1921 Comintern resolution, writing, “A Communist newspaper must be concerned above all with the interests of the oppressed workers in struggle. It should be our best propagandist and agitator for proletarian revolution.

Class character of the press

“Lenin’s merit is that he deprived the bourgeois press of its aura of being a supernatural force … the entire bourgeois press within a capitalist state is a weapon for consolidating the power of the bourgeoisie.” – Baluyev

Within Lenin’s writing, there is an effort to denounce the perceived “objectivity” of the bourgeois press. Lenin showed that the “mainstream” press of his time, while presenting itself as a source of universal truth, actually had a class status and was an ideological tool for maintaining capitalist rule.

The mainstream press today reflects the same capitalist class interests, and helps maintain capitalism and U.S. imperialism. We can easily see these economic and political ties as most big business media outlets are owned by capitalists themselves (e.g. Heath Freeman owns Denver Post, and the Washington Post is owned by Jeff Bezos), they are mainly funded by huge corporate advertisers, and thus, the big business press promotes ideas which affirm capitalist control, both domestically and internationally. Whereas the capitalist press (which Communists should still analyze and use) represents an extension of capitalist power, a Communist Party paper reflects the interests of the working class and puts forward an alternative political program.

An organizing tool for today

“To talk of ‘the political emancipation of the working class’ and of the struggle against ‘tsarist despotism’, it is necessary to conduct the widest possible political agitation among the masses, an agitation highlighting every aspect of Russian absolutism and the specific features of the various social classes in Russia.”

Our party must use the paper to evaluate our work in party clubs and connect this work to the political struggle in a concrete way. As fascist threats continue in the form of anti-Black racism, misogyny, anti-LGBTQ laws, and attacks on reproductive rights, we must have a political voice to direct this energy and concentrate it into building a mass movement. It also necessitates a secure theoretical grounding, to understand the causes and effects of political situations. Party members must work in coalition with mass organizations to deepen and expand the political struggle, to fight against oppression and to draw the connections between various struggles. The newspaper is the form that documents all of these events and connects them most plainly to capitalist exploitation and oppression, and it provides a focus for our organizational work. Our task is to use the Communist press as a tool, like many tools, for agitation and mass organization.

Many aspects of the fight against Tsarism 120 years ago are still present today. Women are under attack from fascist forces; in some states, individuals can be surveilled and arrested for seeking reproductive care. The threat of the “alt right” is apparent as both the state and individual vigilantes are attacking Black individuals. The capitalist system continues to throw people out of work and out of their homes. Our party program must connect the struggles for bodily autonomy, Black liberation, LGBTQ rights and enviromentalism as one mass struggle. We as a party of the proletariat must concentrate these forces and be united in our task of fighting against fascism. The need for the press as an agitational and organization tool for the party and all democratic movements is greater than ever.

The Russian newspapers of the 20th century should serve as an inspiration for connecting our newspaper with the politics of our party. Just as the Bolshevik newspaper created a connection between the political goals of the RSDLP and the working masses who read the publication, we must use our newspaper as a means of building and deepening the political struggle by connecting the mass struggles of our time with our party program. We fight as a unified working-class movement, not only through party activity, but through our press. The Communist Party must use every tool at our disposal to fight against reactionary attack, as every instance of abuse of capital is covered in the press.

We continue to use the press and publications like Peoples World to help working-class and democratic struggles move in the direction of socialism. We must encourage active workshops and help party members submit articles to People’s World. The essential role of the PW as a representative of the working class is a necessary condition for raising class consciousness and building the fight against capitalism. Finally, we must work to strengthen our party press by solidifying our party connections and concentrate our political tasks around the newspaper. We must be critical and continually discuss how to improve our newspaper. The PW sees itself as the voice of the party, the working-class and people’s movement, and part of the independent press. How can we strengthen its mission as the party’s organ and continue to build a newspaper that supports the party’s program and working-class demands? We have seen the effects of this connection between the newspaper and party practice throughout our history, with the incredible work of the People’s World and Daily Worker.

Images: Collage (First Daily Worker issue January 13, 1924 (from Marxists.org), Daily World cropped from “NLN Ken BeSaw.jpg” by Thomas Good (CC BY-SA 4.0/CC BY-SA 3.0/CC BY-SA 2.5/CC BY-SA 2.0/CC BY-SA 1.0), People’s Weekly World 2000 Vol 15 No. 29 American Coup Y (Ebay photo), screenshot of People’s World homepage on Dec. 2, 2009 (retrieved via Wayback machine), screenshot of People’s World homepage on August 2, 2023); John Reed c. 1917 (public domain); The “Daily Worker” float makes its way through New York streets in the 1937 May Day parade by Kheel Center (CC BY 2.0); Philip Bonosky interviewing Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi, 1960 (public domain); January 1937 edition of the Southern Worker (Marxists.org); Ansley Mall Starbucks workers on strike against retaliation and the company’s pride decoration ban by Atlanta DSA (Twitter)

Join Now

Join Now