Note from the author: I first wrote this tribute to Dashiell Hammett for Political Affairs in 2013. Today, literally thousands of books are being banned from school and public libraries by right-wing vigilante groups and Republican-dominated state governments. Pen America, which catalogs such bans, found 3,362 instances of individual book bannings this year, affecting 1,557 unique titles in 33 states, a 33% increase over last year. Today, works dealing in any way with the history of Black Americans and racism, women’s liberation and sexism, and especially LGBTQ equality have joined Marxism and Communism as targets. For those reasons, it is important to revisit and learn from the life and work of Dashiell Hammett and his impact on U.S. culture.

Dashiell Hammett wrote about the class struggle in the U.S. through his works of popular fiction in the 1920s and ’30s. He fought as a partisan of socialism and the working class in real life from the 1930s until his death in 1961. Hammett was many things: a Pinkerton detective, or “fink,” paid to do vicious things during and after WWI; the creator of the U.S. private detective in literature; Communist Party USA activist who lent his name to anti-fascist, pro labor, and Civil Rights causes — despite (or perhaps as a result of) his earlier employment; and a political prisoner in the ’50s under the McCarran “Internal Security” Act, for refusing to turn over the membership lists of a mass organization to the government.

Hammett was a writer for the working class — not for himself, not for art, and not for money, though he, of course, had to do many things to make money. He was an artist who learned from his life experiences and applied those experiences in both literature and life.

Because he was a Communist in the last decades of his life, he became, after his imprisonment in the early ’50s, something of an “unperson,” to borrow a term from George Orwell’s 1984. He was often denied serious credit for the genre he created and subject to condescending putdowns by anti-Communist critics across the political spectrum.

They wrote and taught that was an alcoholic, that he had writers’ block, and that his work wasn’t really “political” in an overt way. Of course, his drinking and writers’ block hardly distinguished him from other writers, and if he had made his politics more explicit in his writing,, his work would likely have been instead dismissed as propaganda. The message was clear: it’s all right to watch the Maltese Falcon or the Thin Man movies, but don’t take Dashiell Hammett seriously, don’t read his works to find out how much Hollywood left out, and certainly don’t relate his art to his politics.

They also wrote and taught that Raymond Chandler (of Philip Marlowe fame was a better writer than Hammett. Chandler also was a heavy drinker, and didn’t produce a huge amount of work, but was politically a liberal and no threat to U.S. aims in the postwar era. Whether he was a better or worse writer than Hammett is irrelevant, since without Hammett there would not have been a Chandler or a John MacDonald, or even that comically crude and right-wing Hammett imitator, Mickey Spillaine, whose Mike Hammer novels reflected the world and the world-view of Joe McCarthy.

This was pretty much the conventional wisdom about Dashiell Hammett when I was in college and graduate school in the 1960s. Even though Hammett would appear as a character in the film Julia in the ’70s, and would be the subject of a PBS dramatization of his life, many who know of Hammett continue to hold to this one-dimensional view.

Dashiell Hammett’s life and work

Samuel Dashiell Hammett was born in Maryland in 1894 in hard times. Dashiell was his mother’s family name, and as he grew up in Baltimore and then Philadelphia, everyone called him Sam.

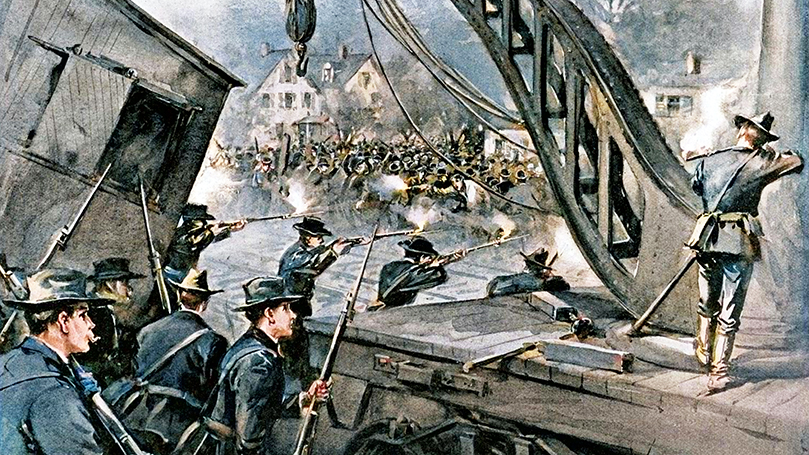

1894 was a depression year, one in which the Cleveland administration smashed American Railway Union and imprisoned its leader, Eugene V. Debs, to break a strike. The union, a comprehensive industrial union, had undertaken the strike to support industrial workers making Pullman cars in the company town of Pullman, Illinois. Two years earlier, a small army of Pinkerton “detectives” (strikebreakers and scabs) had fought it out with unionized steel workers at Homestead, Pennsylvania in another strike that ended in a major defeat for the working class.

Hammett left school when he was thirteen and bounced around from job to job for the next eight years. However, his experiences didn’t lead him to develop the class consciousness that Jurgis, the protagonist in Upton Sinclair’s classic socialist novel, The Jungle, did. Instead, he joined the class enemy, becoming a detective for the Pinkerton agency at the age of twenty-one in 1915.

Here, Hammett found himself involved in brutal Pinkerton espionage, provocations, and strikebreaking against labor, particularly against the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the West. In 1917 Butte, Montana, Hammett was offered five thousand dollars to murder the anti-war IWW leader, Frank Little, who was leading a strike of miners against Anaconda. He refused. Little was subsequently lynched by band of masked men who were generally believed to be either Pinkertons or in the pay of the agency. The police, of course, did nothing to apprehend the culprits.

Hammett volunteered to serve in WWI and served as an ambulance driver until he became a victim of the global flu epidemic which was to kill millions at the war’s end and in the immediate postwar period. He also contracted tuberculosis. While he survived, TB remained a chronic problem for the rest of his life, producing further respiratory problems.

Hammett went back to working for Pinkerton after the war, but with a commitment to use his work to write. He also began to drink heavily, perhaps as self-medication because of his health or the wretched nature of his work.

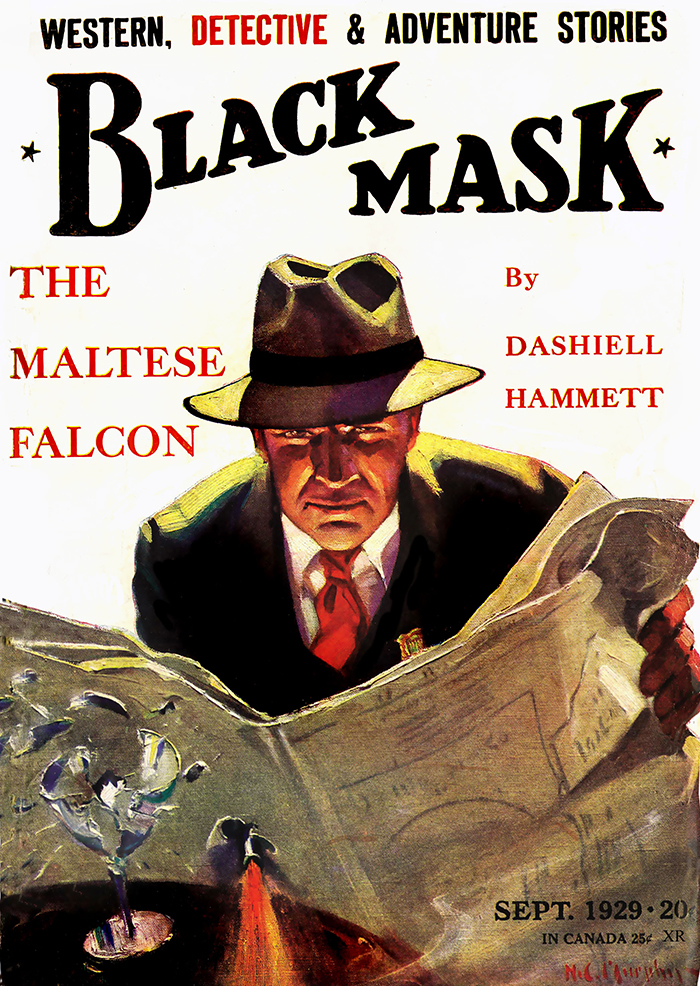

Hammett left the agency in 1921 and began to write crime fiction based on his experiences. Many of these works were published in Black Mask, at the time the best known magazine for the genre.

Unlike the characters created by earlier and contemporary crime writers, such as Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Agatha Christie’s Hercules Poirot, and later protagonists (not to mention the Lord Peter Whimseys, Charlie Chans, or Mr. Motos), Hammett’s detectives were neither elite figures nor exotic characters. The central character in the early stories was a nameless detective called the “Continental Op.” In 1928, Hammett published his first novel, Red Harvest. Another, The Dain Curse, followed, and readers of detective fiction began to realize that he represented something that was both new and remarkable

The elite and exotic figures in Hammett’s stories were usually the criminals and they often had powerful allies in the establishment to assist them. Also, the motif of the stories, even if they often took wild unrealistic turns, was not to unravel the mystery, but to follow the action as the detective, who, with a sense of honor and justice — even if his employers had neither — sought to do his job. As Hammett developed as an artist, his villains also became more realistic.

In 1930, Hammett wrote what is still his best known novel, The Maltese Falcon, introducing Sam Spade, who would be the prototype for the American “private eye” for generations. The Maltese Falcon would be made into two movies before the classic 1941 version starring Humphrey Bogart. Sam Spade would also have his own radio show and would eventually influence aforementioned Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, Mickey Spillaine’s misanthropic Mike Hammer, as well as private eyes that would be featured in movies and on television, figures like Richard Diamond, Mannix, James Rockford, and many others.

The search for a mythical treasure led to betrayal and murder in The Maltese Falcon. In Hammett’s next novel, The Glass Key (1931), which was made into a successful film starring Alan Ladd in 1942, the authorities and the criminals operate through the worlds of business and politics as a kind of interlocking directorate.

The Glass Key gained Hammett a major literary reputation and entry into literary circles. Coming to Hollywood in 1930 after The Maltese Falcon, he met the playwright Lillian Hellman, and established a relationship with her which lasted for the rest of his life. In 1934, his last major work The Thin Man was published and became a great success.

The Glass Key gained Hammett a major literary reputation and entry into literary circles. Coming to Hollywood in 1930 after The Maltese Falcon, he met the playwright Lillian Hellman, and established a relationship with her which lasted for the rest of his life. In 1934, his last major work The Thin Man was published and became a great success.

The Thin Man led to a series of movies starring William Powell and Myrna Loy. Eventually, its upper class New York amateur detectives created another genre character, which spawned many imitators — from the 1950s television series, The Norths, to the better-known ’70s television series, Hart to Hart. The latter co-starred, ironically, the blacklisted actor Lionel Stander, who had gone to Italy in the ’50s to work in Italian films after he blasted HUAC as a very unfriendly witness.

While some have seen The Thin Man as in the tradition of English upper class sleuths in the mold of Agatha Christie’s Tommy and Tuppence characters of the 1920s, this novel’s Nick Charles has a particularly complicated relationship with many underworld characters (who aren’t that different than the cops). While they do exude glamor, the alcoholic haze in which they wander does not make them sterling representatives of their class to be admired, as much as it does characters to be either laughed at or pitied for their aimlessness.

After the rise of Hitler in Germany, Hammett was to devote much of his energies in the 1930s and ’40s to the struggle against fascism and for workers’ rights. He became a leader of the League of American Writers, the mass organization that the CPUSA played a leading role in creating in the ’30s and which sought to both represent writers as workers and also to encourage pro-working-class and anti-fascist work.

Hammett’s political work and personal integrity limited his success as a screenwriter in the Hollywood studio system. Although his political enemies would mock him for his drinking and partying (portraying him in many respects as a kind of real life Nick Charles, which he didn’t especially mind), he worked to fight fascism, racism, and anti-Semitism. Meanwhile, they spent these times criticizing the policies and members of the Communist Party.

Old myths died hard and this one, similar to the right-wing attacks on “radical chic” in the 1960s and “politically correct” artists today, served the interests of those who wished to either condemn or dismiss Hammett’s work and his politics.

While CPUSA members like Hammett and close allies of the party worked in Hollywood’s studio system as writers, directors, and actors (there were even technical people working as scenic designers and cameramen) they did so because their work — particularly those who made or had performed in films sympathetic to the urban working class — generated commercial and artistic success for the studio owners.

It was always much easier and more lucrative to be a B-level movie actor like Ronald Reagan, or a second-rate movie writer or director, and produce work for the studio system based on establishment formulas.

Communists and their allies, whatever the quality of their work, often sought to work within those formulas to make films that portrayed the working class more positively. They always faced substantial harassment from conservative elements in the Hollywood industry — from labor racketeers in the technical unions to right-wingers among the writers and directors to the studio owners, who fought the successful campaigns of Communists and progressives. The conservative unions of writers, actors, and directors fought them as actively as capitalists everywhere in the 1930s fought the campaigns to organize workers in all industries.

Hammett was part of this struggle and his popularity as a writer made it easier for others to join in and become activists.

During WWII, Hammett actually fought to rejoin the service. This was an incredibly courageous, albeit quixotic act, given both his age (he was forty six) and the fact that he had suffered chronic disabilities from his World War I service. Subsequently, he edited the local army newspaper while stationed in the Aleutian Islands in the Pacific. The service intensified his respiratory problems, adding emphysema to his list of ills.

His wartime service as a writer and organizer contributed to the war effort. In the postwar era, however, he and his comrades would become the hunted, just as Frank Little and his IWW comrades were hunted at the end of WWI. After the war, U.S. government agencies and the military began to remove his books from U.S. State Department libraries all over the world, a censorship similar to what is happening today to a wide variety of writers in many fields.

Although he was very famous, Hammett taught courses at the CPUSA-supported Jefferson School of Social Science, in which teachers, many of whom had already been victims of blacklisting, provided working-class people with an open, non competitive college education, from 1946 to 1956. At this time, Hammett became active as a supporter of the Civil Rights Congress, a new, left-led, militant Civil Rights organization, which one can read about in Gerald Horne’s Communist Front.

Although far less so than his lifetime companion, Lillian Hellman, Hammett participated in the circles of artists and intellectuals to mobilize opposition to the postwar Red Scare. Albeit less violent and terroristic physically than the post-WWI Red Scare in the U.S., the McCarthyite repression was far more comprehensive, and of much longer duration. This was because it served as a major foundation for the global Cold War, as it expanded and intensified into the NATO alliance, the nuclear arms race, the Korean War, and a “defense” budget that rose from twelve billion shortly after WWII to over forty billion a decade later.

Hammett served five months in federal prison in 1951 for his refusal to name names, hand over lists, or collaborate with HUAC.

Under the McCarran “Internal Security” Act of 1950, a “Subversive Activities Control Board” (SACB) was created, in effect to institutionalize HUAC’s use of media to red-bait and of “hearings” to intimidate its prey for a national audience. The board had the power to demand that organizations labeled “Communist front” groups register with it and turn over their membership lists. Refusal to comply meant prison sentences, which theoretically could be of a long duration and huge fines, which practically could bankrupt the organization.

Besides these effects, the purpose of the legislation was to intimidate members of such organizations (the mass organizations of the left) into withdrawing their membership and dissuade potential members from joining. It also aimed to consolidate and institutionalize a political climate of repression. Any organization could be listed by the board, and the only way for organizations to “protect themselves” was to do the work of the state inquisition by carrying out internal purges of their own and steering clear of militant positions and mass protest tactics.

Hammett’s refusal to name names or turn over lists should be seen in this context. After his release, the IRS continued the work of the HUAC and SACB, going after everything he had left financially. This left him financially dependent on Lillian Hellman, even as TV continued to produce series based on, or derived from, his work. Today, if one is to take Donald Trump’s fascist threats seriously, a second Trump administration might very well see the arrest of people who refused to turn over the membership lists of progressive mass organizations and the use of the IRS to bankrupt individuals and groups who opposed Trump.

Having been in ill health since WWI, Hammett spent the last decade of his life living with Lillian Hellman, who continued to work in the New York Theater after her blacklisting and became a heroine to the anti-McCarthyites because of her eloquent resistance to HUAC in 1952. Hammett died in 1961 of lung cancer. The literary genres that he largely created continued to attract large audiences among readers of crime fiction, movie goers, and most of all, television viewers. As a veteran of both world wars, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Restoring Hammett to his rightful place

Hammett joined the CPUSA shortly after he completed all of the work for which he is justly famous. Nonetheless, many critics who either ignored or qualified his major literary contributions and disparaged his lifestyle — singling him out from among the legions of successful writers and artists who lived that way — did so consciously or unconsciously because they could not, even within the limitations of their own critical standards, deal seriously with Communist artists.

Hammett joined the CPUSA shortly after he completed all of the work for which he is justly famous. Nonetheless, many critics who either ignored or qualified his major literary contributions and disparaged his lifestyle — singling him out from among the legions of successful writers and artists who lived that way — did so consciously or unconsciously because they could not, even within the limitations of their own critical standards, deal seriously with Communist artists.

They would have to either ignore his political convictions, commitments, and associations or find ways to disparage and trivialize his work. This was usually the way U.S. critics treated other Communist artists, like Irish playwright Sean O’Casey, who was a member of the Communist Party of Ireland, or the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, a member of the Communist Party of France, both of whom were world famous cultural figures.

Hammett, however, received and continues to receive tribute from his peers — the writers that he influenced and whom conventional wisdom has treated more respectfully. Among these were Ross MacDonald, whose crime novels (especially his Lew Archer novels) were among the postwar era’s most successful, commercially and aesthetically. MacDonald said of Hammett: “as a novelist of realistic intrigue, Hammett was not surpassed in his or any other time … We all came out from under Hammett’s black mask,” referencing the magazine in which much of his work appeared.

Tony Hillerman, known for his remarkable crime novels which portray with sensitivity and great insight contemporary Native American people, wrote, “if not the greatest, Dashiell Hammett is certainly the most important American mystery writer of the twentieth century … and second in history to Edgar Allen Poe, who essentially invented the genre.” Poe’s mid-nineteenth century Murders in the Rue Morgue had paved the way, along with his invention of the first fictional detective, Auguste Dupin.

Contemporary mystery novelist Donald Westlake, author of Point Blank, The Hot Rock and screenwriter of The Grifters, considered his reading of Hammett’s The Thin Man as a young teenager “a defining moment” in his development as a writer. “It was a sad, lonely book that pretended to be cheerful and of good fellowship … three dimensional writing like three dimensional chess.”

Finally, Raymond Chandler — who also made his way into the Hollywood studio system and whom critics have placed above Hammett in the literary pantheon, sometimes to the point of giving Chandler more credit for the development of the private detective genre than Hammett (despite evidence to the contrary) — looked at it very differently. “Hammett,” he argued, “wrote at first (and almost to the end) for people with a sharp, aggressive attitude to life. They were not afraid of the seamy side of things; they lived there. Violence did not dismay them; it was right down their street. … Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse. … He put these people down on paper as they are.”

If literary realism is important, and if the experiences of the class struggle in forming the consciousness of an artist are important, then Dashiell Hammett is an enormously influential writer. Hammett took his experiences with the Pinkerton Detective Agency and made it the basis for a literature in which greed, exploitation, and corruption were motivations for both criminals, elites, and authorities.

If artists should use their success and celebrity to work actively for social progress and social justice — as many did in the 1930s in the U.S. and subsequently — and not to achieve more fame and celebrity, then Dashiell Hammett is an enormously significant writer. His experiences on the “wrong side” of the class struggle for many years, as a servant of capitalist power structures, led to major literary works that reached millions throughout the world, both in the stories and novels themselves as well as in movies, and on television. Those experiences also led to a life of political commitment to the Communist movement that put him on the right side of the class struggle.

It is important that Hammett’s achievements as a writer continue to grow in significance and prestige. More readers and critics should understand the importance of his work to the interdependent worlds of art and politics.

Images: Dashiell Hammett “Thin Man” portrait, photographer unattributed (public domain), colorized using palette.fm; “National Guardsmen firing into the mob [striking workers] at Loomis and 49th Streets, July 7th” by by G.W. Peters, from a sketch by G.A. Coffin (public domain), colorized using palette.fm; Lillian-Hellman by Stage Publishing Company, Inc. (public domain); Farewell at the Los Angeles Airport on June 8, 1950 as many of the Hollywood 10 head to jail (Zinn Education Project); Black Mask Vol. 12 by Henry C. Murphy, Jr. (public domain)

Join Now

Join Now