“No one in the wealthiest country in the world should be forced to sleep on the streets.”

Congressperson Ilhan Omar tweeted this statement in 2019 when she introduced the Homes for All Act. The bill, HR 5244, came at a critical time as the cases of homelessness nationally were on the rise, but Rep. Omar’s effort was hardly the first attempt to counter more than a generation of anti–public housing policy.

According to Rep. Omar’s press release at the time, the bill would “authorize construction of 12 million new public housing and private, permanently affordable rental units, driving down costs throughout the market and creating a new vision of what public housing looks like in the U.S.”

With a $1.2 trillion price tag spent over 10 years, the bill would have been “a new mile marker in the progressive left’s efforts to stake out a national housing agenda,” according to CityLab.

Housing justice experts and activists fervently praised the bill. The Center for American Progress said that it would be “life-changing for millions of families.”

“Every American deserves access to a safe and stable place to live, but unfortunately, our current free-market housing system is not meeting the needs of working families,” said Rep. Omar.

Nevertheless, HR 5244 fizzled into obscurity, joining the graveyard of a few substantive and many rhetorical plans to address the homelessness crisis.

Ultimately, the bill gained only six cosponsors, including Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, Ayanna Pressley, and Pramila Jayapal.

Why do efforts like this, despite a growing crisis none of us can ignore, continue to fail?

Recall that, back in 2005, Rep. Julia Carson (D-IN) introduced the Bringing America Home Act, which was quickly cosponsored by other progressive, left-leaning Democrats, including Dennis Kucinich of Ohio, Barbara Lee of California, and John Conyers of Michigan. It was also cosponsored by the Independent representative Bernie Sanders of Vermont, then chair of the Progressive Caucus.

Like Omar’s 2019 bill, Carson’s bill did not make it out of committee and received no vote.

While a lot of angst from all quarters is stirred over the homeless crisis — from homeless advocates who demand remedies, the homeless themselves who need homes, local business owners, realtors anxious about property values, and state and local politicians — very little is achieved to end the crisis.

In fact, the crisis of homelessness continues to be foreshadowed by the rising Housing Insecurity Index, a tool developed to measure things like food insecurity and delinquent rent payments. The less-discussed precariousness of many renters puts them on a direct path to sleeping on the streets, in shelters, and in their cars. Shamefully, we live in a “market system” that continues to normalize the depths we fall to by addressing none of the things that create this precariousness but often attributing this crisis to drug abuse or mental health issues, when some activists on the ground push back on this assertion.

A report from Street Roots in Portland, Oregon, sounds the alarm and takes aim even at the Biden Administration’s developing policies. Street Roots finds the new administration’s efforts sorely wanting:

The data . . . suggests that the scale of the country’s affordable housing crisis is much greater. . . . 7.7 million families in 2017 had “worst-case needs.” Worst-case needs are defined as renters making less than 50% of the Area Median Income without housing assistance and living in “severely inadequate housing,” renters paying more than half of their income in rent, or those doing both.

The Street Roots report concludes: “Almost all households with worst-case needs (98%) pay more than half their income for rent, an untenable situation that puts people at risk of homelessness.”

This “untenable situation,” in other words, is a ticking bomb that could be triggered at any time, sending more people into the ranks of the houseless.

Rep. Omar, like Rep. Carson and others, are not revolutionaries. They sought only to mitigate the coarse effects of “the free-market system” that structurally is “not meeting the needs of working families.” And even this was not allowed.

Sub-prime disaster

One of the biggest of capitalism’s structural failures was the sub-prime mortgage crisis of 2007–10. It helped bring on the Great Recession and led to massive numbers of foreclosures and evictions not seen since the Great Depression. Over 4 million homes were foreclosed on between 2007 and 2011, and African American and Latino homeowners were disproportionately affected. Sub-prime mortgages, which have higher interest rates than standard mortgages, are sold to borrowers with bad credit histories (predatory lending). Following bank deregulation and mergers in the 1990s, big lending institutions like JP Morgan Chase began bundling high-risk, sub-prime loans and selling them to Wall Street investors as “securities.” This practice fueled the housing bubble, in which home prices increased dramatically. Then the housing bubble burst, prices declined, and homeowners, facing rising unemployment and income loss, defaulted on their mortgages. This structural failure of capitalism led to more homelessness: in 2009 170,000 families, or over half a million people, were homeless, an increase of 39,000 families over 2007; and in 2009–10, homelessness in 26 major cities rose by 9%. This does not count the numbers of people doubling and tripling up in the homes of their families and friends.

Border wall against public funding

The current homelessness crisis could mitigated by more public housing. But capitalism in its neoliberal stage has built a border wall to block public funding of any kind. Be it public schools, public health, or public housing, the neoliberal paradigm has shifted away from the concept of the public sector as actor to one favoring what private business can do “to be a good neighbor.” So, while public schools are allowed to be underfunded, privately run charter schools flourish and public vouchers are redeemed at private and parochial schools.

This is an alarming trend that needs to be reversed. Politicians like Omar have tried to reverse this trend, but they are outliers.

To understand how we got here, let’s review the origins of the current homeless crisis and some of the major “reforms” that have instead worsened people’s access to housing.

Tough love for the poor

Around 40 years ago, with the ascendancy of Ronald Reagan, former FDR Democrat and labor leader turned right-wing Republican, a seismic shift happened. By 1981 housing affordability was already a crisis that the Carter administration did little to resolve. But Reagan made things worse by gutting the Housing & Urban Development (HUD) in his first budget. As Shelterforce reported, “Reagan halved the budget for public housing and Section 8 to about $17.5 billion. And for the next few years he sought to eliminate federal housing assistance to the poor altogether.”

The cuts did not end when Reagan completed his two terms. His successors, Republican and Democrat, made further cuts to these programs — always for allegedly noble reasons — virtually eliminating the nation’s commitment to public housing by the time of Clinton’s regime. (It’s interesting that few will connect the dots between Clinton’s contribution to the war on the poor’s housing, his criminalization of the urban poor with the Omnibus Crime Act, and the swelling of the prison-industrial complex.)

Section 8, incidentally, provides generous housing subsidies to its participants to access rental units in the private market. This itself has proved to be a problem, but the cuts made to the overall HUD programs created longer waiting lists, and private landlords increasingly refused to accept Section 8 vouchers, thus exacerbating the housing crisis.

The existential anxiety felt by many in the Section 8 program begins with the waiting lists, but even after a renter secures housing, a private owner can opt out of the program, sending the recipient to look for another landlord who will accept the vouchers.

With “good” neoliberal intentions, the Clinton administration sought to replace 30,000 units of the worst public housing with “townhome-style developments,” “[crack] down on bad management in public housing by taking over the most troubled public-housing authorities,” change “admission rules and rent calculations to reward working families,” combine HUD’s 60 programs into three “flexible performance-based funds,” and combat crime, according to 4President.us.

Instead, the nice-sounding policy yielded dire consequences.

For example, in the name of “combatting crime,” the aggressive “one strike and you’re out” policy threw whole families out of their public housing units. It made no distinction between drug kingpins and low-level dealers, most often Black and Latino young men whose areas had suffered Reagan-era de-investment.

What happened to those thousands of public-housing residents whose only home was torn down? Does anyone think they were placed into “townhome-style developments”?

While the Clinton regime postured to go after “the worst” and to “combat crime,” his two predecessors had already made draconian cuts to public housing programs and essentially left them prone to Clinton’s demolition team. And this is what happened.

Scrutiny

Of course, these official transgressions against the working class have not gone unnoticed by the CPUSA. In 2001 the Party posted Carol Trowbridge’s speech on homeless women in which she offered contemporary grim statistics on how women were impacted. Cameron Orr’s piece from 2019, on the same site, details the collaborative work the New York District is doing with other grassroots and political organizations.

U.S. policy came under the scrutiny of Human Rights Watch (HRW) in an extensive 2004 report, “No Second Chance: People with Criminal Records Denied Access to Public Housing.” The report targets housing policies from Reagan to George W. Bush, and specifically indicts Clinton’s “One-Strike” policy: “By requiring strict admissions policies, the federal government has tacitly adopted a method of ‘triage’ to whittle down the numbers of qualified applicants. Excluding those with criminal records has proven to be a politically cost-free way to entirely cut out a large group of people from the pool of those seeking housing assistance.”

HRW goes further: “U.S. housing policies are so arbitrary, overbroad, and unnecessarily harsh that they exclude even people who have turned their lives around and remain law-abiding, as well as others who may never have presented any risk in the first place.”

San Francisco, which up to the 1990s had an established homeless encampment on the grounds in front of its City Hall, implemented a Clintonian, get-tough policy under its first Black mayor, Willie Brown. The ominously titled Matrix Program was widely criticized until its demise in 1996.

But rather than provide homes, the city continued to attack the homeless. In 2018, a United Nations human rights official on a year-long tour of global encampments, which included sites in Belgrade, Buenos Aires, Delhi, Lisbon, Mexico City, Mumbai, and Santiago, visited San Francisco. The report indicted San Francisco and nearby Oakland: “Attempting to discourage residents from remaining in informal settlements or encampments by denying access to water, sanitation, and health services and other basic necessities, . . . constitutes cruel and inhuman treatment and is a violation of multiple human rights, including the rights to life, housing, health and water and sanitation.”

Recently and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Peter Hepburn of the Eviction Lab and Emily Benfer of the American Bar Association reported grim findings from the eviction moratorium: “Across six states and 31 cities . . . throughout the pandemic, landlords have submitted 351,816 eviction filings since the CDC moratorium was enacted,” suggesting how vulnerable even those currently sheltered are, even under the moratorium. Hepburn and Benfer note the number of eviction filings is roughly half that of pre-pandemic levels, but express alarm that even with the moratoria, the filings would still be that high.

While there is no inevitable pipeline between an eviction and houselessness, eviction, as well as bankruptcy, often bar many people from renting in the future.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Hepburn has elsewhere found that most of the evicted were women and evictions disproportionately impact Black renters.

Neoliberal solutions

The official response to this critical problem has always been lacking because the needs of the homeless remain subservient to real estate and construction lobbies. But one response especially reveals the impotence of our political class: the designation of parking lots as safe places for the homeless to sleep in their cars. This most shocking of remedies is a recent innovation, and it has taken hold in California.

Santa Barbara was an early site of this project. Back in 2008, during the Great Recession, news reports detailed the rise of homelessness in wealthy Santa Barbara County. A local ABC-News affiliate reported, “And now the city has a new class of resident, not quite homeless — but doesn’t have a home either. They are the working poor who live in their cars, trucks, and campers. Call them the mobile homeless.”

The city tried to fight the county’s project but saw it was a losing battle. So currently, 26 parking lots are designated in the county for sunset-to-sunrise use.

Not surprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic and end of eviction moratoriums have made things worse, prompting the county to allocate money for 80 additional “Safe Parking spaces.” But the county has been struggling to find new parking lot owners “willing to join the program,” according to Britain’s Independent.

Who makes up the new “mobile homeless”? “About 84 percent of the guests … are 55 and older; 70 percent are men; one third are working. Very few … have substance-abuse issues. ‘Many do not consider themselves homeless,’” said the director of Santa Barbara’s Safe Parking Program.

San Diego, San Francisco, and Los Angeles County have followed suit, and now have similar Safe Parking programs to address the rise in homelessness. San Francisco established a “Vehicle Triage Center” near the old Candlestick Park, which, according to California Assemblymember David Chiu (D-San Francisco), “will bring badly needed security, services, and hygiene facilities to the Candlestick Point Recreation Area.”

“The center will improve conditions for all Candlestick Point residents and help connect those living in their vehicles to permanent housing solutions.” By “residents,” Chiu means those who have homes who resisted the Vehicle Triage Center.

Biden’s solutions

In September 2021, the Biden administration announced the formation of House America: An All-Hands-On-Deck Effort to Address the Nation’s Homelessness Crisis, headed by HUD secretary Marcia Fudge, who also chairs the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH).

“It’s going to take government working at all levels and local collaboration to address homelessness and to guarantee housing as a right for every American,” says Secretary Fudge in a press release.

It remains to be seen whether this monumental project will be fully funded, partly funded, or cut entirely from Biden’s Build Back Better proposal, a $1.75 trillion “human infrastructure” bill. While initial proposals did not specifically address public housing, the House America’s proposal for a Community Revitalizaton Fund would go a long way in resolving related issues to abandoned and underserved communities.

Better solutions

To echo HRW’s criticism, what would “the goal of dramatically increasing the availability of affordable housing” look like? Rep. Omar’s unsuccessful bill, and those like it that center the recommitment to public housing is the best course of action to achieving affordable housing. As it stands, private owners now have a near-total monopoly on the nation’s housing market. They determine who gets in and who stays out. As long as these interests are supported by federal, state, and local governments, affordable housing will never reach masses of people.

HUD stepping in and building public housing will undercut the monopoly on housing and eventually drive the price of rental units down. This is a win-win for the poor and working class, since those below the poverty line will have access to housing, and the working poor and low-income can better access units on the private market.

HUD stepping in and building public housing will undercut the monopoly on housing and eventually drive the price of rental units down. This is a win-win for the poor and working class, since those below the poverty line will have access to housing, and the working poor and low-income can better access units on the private market.

Let’s renew the demand for public housing in conversations, public statements, and meetings with elected officials. This demand must include properly funding the Section 8 Program. And while affordable housing is critical, we should be specific in our demand for the construction of public housing. Too often the fine print behind affordable housing keeps low-income and working-class renters out, as their rents are priced at a certain percentage below market-rate housing on the same properties — at rates still too high.

Clinton’s “one-strike” must be repealed. Men and women who have paid their debt and served their time have the right to housing.

Let’s demand and fight for a national rent-control policy. In many metropolitan areas, rents can rise ostensibly with market assessments of the area, and without regard to our stagnant wages.

Speaking of wages, let’s double down on our support for union organizing, which can lead to better wages not only for the working class broadly but also for women and African Americans, two groups cited by Eviction Lab as being disproportionately evicted.

As Street Roots in Portland has pointed out, the homelessness crisis doesn’t begin with living on the streets or sleeping in a car. It begins with the housing we increasingly cannot afford to live in.

The homelessness crisis is a housing crisis. Commitments to well-constructed public and affordable housing are the critical solutions. Rep. Omar rightly identifies the “free-market housing system” as an obstacle to meeting the needs of workers and their families. This acknowledgment should be our starting point to resolving the multifaceted problems that feed the pipeline to housing insecurity and homelessness. It demands that we look at other models outside capitalist imperatives to address this basic human need.

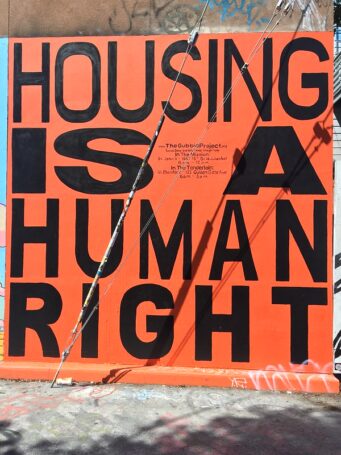

Images: Rent protest, Informed Images (CC BY-NC 2.0); Homeless encampment, Charles Edward Miller (CC BY-SA 2.0); Brewster-Douglass public housing in Detroit, closed in 2008, Juan N Only (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Housing rally, Brooke Anderson (CC BY 2.0); Housing is a Human Right, Karl Schultz (CC BY-NC-SA).

Join Now

Join Now