The U.S. government has become obsessed with Africa. Not with fostering its strength, independence, health, or economic development, mind you. Instead, it is worried about why Africans don’t like us much. Recent polling in 29 African countries shows that African youth hold more favorable opinions of China than of the U.S. More than eight in 10 respondents see China’s influence in their country as both more prominent than that of the U.S. and more positive. Upbeat views of China are nearly unanimous in Nigeria, Malawi, and Uganda.

Separate data reveals that since 2015 the number of African students from English-speaking countries who gained admission to Chinese universities surpassed that of those who attend universities in the U.K. and the U.S.

This data shows a considerable shift in African perceptions of China, to the detriment of the dominant neocolonial powers.

After four centuries of the European/American slave trade, colonialism, and neocolonialism, followed by decades of neglect, the U.S. government in 2021 called Africa “the southern flank” of NATO. Large chunks of the massive annual $800 billion military budget fund the complex of military installations, intelligence networks, and interventionist political projects called AFRICOM.

After four centuries of the European/American slave trade, colonialism, and neocolonialism, followed by decades of neglect, the U.S. government in 2021 called Africa “the southern flank” of NATO. Large chunks of the massive annual $800 billion military budget fund the complex of military installations, intelligence networks, and interventionist political projects called AFRICOM.

In Political Affairs 15 years ago, Gerald Horne noted the U.S. government’s growing concern about China’s deepening relations with African countries. At the time, the Bush administration expressed frustration that they could not disrupt that relationship. They predicted that if China were allowed to continue in that manner, U.S. imperialist hegemony would wane. Time has proven this forecast correct.

This transformation in the global state of affairs has resulted from the rise of China, the developing independence of Global South countries, and a related decline of U.S. hegemony.

End AFRICOM

Given the diminishing U.S. ability to compete economically, it intends to create a position of force against African countries. By linking NATO and AFRICOM in a global military alliance against China, it plans to ratchet up dangerous U.S. interventions in that part of the world.

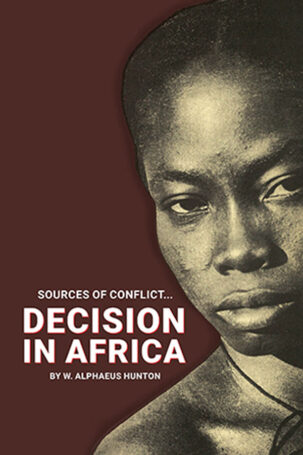

The U.S. sees Africa through a narrow, racist lens: a site of struggle for Western imperialist domination. Today’s Western interventions in Africa — historically rooted in the European slave trade, colonialism, and neocolonialism — “must be seen through a dependency perspective.” W. Alphaeus Hunton, in his groundbreaking study Decision in Africa, detailed the historical continuity between European colonialism and U.S.-led neocolonialism in Africa.

He showed that Western loans and foreign direct investment in Africa functioned primarily to 1) extract wealth (minerals, energy, and agricultural products); 2) bring this wealth to seaports in raw form for export to metropoles; 3) maintain comprador relations with state political forces; and 4) ensure internal security of the Western imperialist project. Those forms remain unchanged. The side-effects produced sharper inequalities, provided little traction for anti-poverty initiatives, negated autonomous capacity for development, and reduced political sovereignty.

He showed that Western loans and foreign direct investment in Africa functioned primarily to 1) extract wealth (minerals, energy, and agricultural products); 2) bring this wealth to seaports in raw form for export to metropoles; 3) maintain comprador relations with state political forces; and 4) ensure internal security of the Western imperialist project. Those forms remain unchanged. The side-effects produced sharper inequalities, provided little traction for anti-poverty initiatives, negated autonomous capacity for development, and reduced political sovereignty.

Western-derived loans, grants, aid, or foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries have streamed toward dominant classes sympathetic to Western goals. Western-originated lending and investment favor the wealthiest, least financially risky sites. This situation produces an “excessive concentration of economic activity” around already successful, powerful actors. Those lending practices exclude those classes and sectors that need the most direct stimulation.

New plans for infrastructure projects projected as part of the Build Back a Better World initiative, which the Biden administration plans to help rebuild U.S. control over Africa, will no doubt function similarly.

The U.S. government has never tried to promote equal relations between itself and African countries. It cares little for that continent’s human rights issues, democracy, or economic development, except insofar as it can use these issues to impose its will.

What is development?

In How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Walter Rodney defined truly free national development in these terms:

- higher levels of economic and political equality within a country

- the complexity of production (raw to finished outputs) controlled by entities belonging to the nation (preferably public entities)

- the capacity for autonomously produced technical and creative capacity

- complex, necessary, and productive social services

- the ability to center a planned concept of improved people’s well-being.

Sovereign control, rather than dependence on an outside entity, such as a foreign-owned corporation, a Washington-dominated financial apparatus, or a cadre of political operatives under the direction of a foreign government, was Rodney’s key ingredient. Historically, this has never been the goal of the U.S.

Today is no different. A top U.S. military official admitted as much in a 2020 congressional hearing. AFRICOM’s commander warned that China’s growing influence undermined U.S. domination. Without a sense of irony, he labeled China’s increasing role in African economic development as “coercive and exploitative activities.”

His language, repeated on cue in the U.S. media, distorts China’s actual role in Africa, cynically and falsely portraying it as a U.S. enemy.

Unfortunately, this official Western/imperialist view of China-Africa relations has also seeped into radical circles. It is commonplace for some U.S. and U.K. leftists to denounce China as imperialist. In so doing, they display little knowledge of the precise relationships it has tried to develop with African countries.

What is the situation?

There is little space here to explore and document Africa’s full diversity and complexity, with 54 countries and 1.2 billion people, more than 1,000 languages, dozens of traditional and modern religious orientations, 3,000 ethnic groups, varied ecosystems, diverse political orientations, and complex histories. Still, the following data opens a tiny window into the developing China-Africa paradigm.

African agriculture makes up about one-third of the continent’s total GDP, employing about 60% of the African workforce. Even to this extent, African countries have not yet reached the continent’s “full potential in agriculture.” Researchers show that Chinese policymakers are carefully attending to the necessity of building on the agricultural sectoral as a base for “structural development economics.”

Forty-nine countries have established financial relations with China through loans and grants for seaport construction or expansion, hydroelectric dams, standard gauge railways, highways, roads, bridges, technical training facilities, medical support, and agricultural projects. Why infrastructure? One estimate shows that current infrastructure conditions restrain growth throughout Africa by at least 1% of annual GDP growth rates.

Between 2002 and 2012, China earned high praise from humanitarian watchers for delivering loans and grants with few political strings, regular low-interest rates, and generous repayment conditions. After the 2008 recession, the Chinese government canceled 168 African debts to enable a return to economic growth on the continent.

Since 2013, with the establishment of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), some growth in Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) — separate from government-backed loans or grants—spurred the development of the number of Chinese-owned and operated businesses in Africa. Today, about 10,000 Chinese businesses operate in African countries, with at least 1 million Chinese citizens living on the continent.

Chinese-African trade totaled $200 billion in 2015, and China has become the continent’s single largest trading partner.

Chinese investments in infrastructure, FDI in the development of African energy and mining sectors, and material aid in the form of hundreds of medical and educational missions are premised on mutual benefit. In other words, the Chinese government regards international relations as a vehicle for stable political relations and trade.

On the one hand, trade provides each side with various products, labor resources, and earnings for private and public enterprises. On the other, they create new opportunities for technical and cultural development and the transfer of modernized agricultural and industrial capacity from China to African countries.

Up to 2019, Chinese investments in Africa drove an average 4% GDP growth rate. Only halted by the pandemic, average growth fell to 1.4% in 2021, mirroring global trends.

“Debt trap” or “African agency”?

The mutual benefit idea causes some Westerners to be suspicious of China’s lack of pure altruism. U.S. officials and media pundits have incorrectly claimed that China aims to manipulate African countries. Some call it a “debt trap”; others warn of new imperialism.

A recent analysis of the realities, however, has noted that “the inclination to characterize Africa’s debt crisis as Chinese-designed is deepening global political and financial tensions.” Blaming China hides the reality. African countries have been able to pay off about 75% of Chinese-held debt since 2000. Accusations that China is driving African debts (the overwhelming majority of which is held by non-Chinese actors) are “clearly hyperbolic.”

Still, African debt to China totals $143 billion, or about 15% of the continent’s indebtedness.

(By comparison, China holds slightly more than $1 trillion of U.S debt.) While some researchers describe the situation as “disquieting,” it isn’t clear for whom this situation is so disturbing. Suddenly, many who have never uttered similar fears of U.S. or European dominance (often brutal) are concerned about African sovereignty.

Since the 1940s, the U.S. has controlled global indebtedness to manage the domestic policies of other countries. When U.S-dominated institutions couldn’t impose their will, they often withheld aid, imposed sanctions, or directly intervened with military force or other forms of power.

In the 1990s, World Bank–ordered structural adjustment programs (SAPs) favored the consolidation of massive monopoly landholdings and large-scale capital through privatization, freezing small farmers out of agricultural markets, deepening inequality, and providing zero relief for poverty. Indeed, a prominent (intentional) feature of most SAPs was proletarianization, loss of traditional land holdings, and internal social upheavals.

In the 1990s, World Bank–ordered structural adjustment programs (SAPs) favored the consolidation of massive monopoly landholdings and large-scale capital through privatization, freezing small farmers out of agricultural markets, deepening inequality, and providing zero relief for poverty. Indeed, a prominent (intentional) feature of most SAPs was proletarianization, loss of traditional land holdings, and internal social upheavals.

In contrast, researchers found that China doesn’t “seize assets” or force privatization. It doesn’t demand international arbitration for defaults. Instead, it generously offers occasional cancellation but most often negotiates loan restructuring and refinancing. This approach allows borrowing countries to retain ownership of resources and enterprises and complete needed infrastructure projects.

Recent research on East African dynamics provides a detailed example. Many East African countries have taken advantage of Chinese-originated loans, which are accompanied by a hands-off policy, generous repayment schemes, and restructuring processes. The impacts of two major Chinese-backed infrastructure projects in East Africa (a regional energy pipeline and a standard gauge railway system) show concrete positive outcomes. Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Burundi, Tanzania, South Sudan, and Rwanda have been the direct beneficiaries.

The full impact of these two infrastructure projects is yet to be fully realized, but they are expected to increase international trade in that region by five times.

In addition, these two projects aided the East African Community’s (EAC) resuscitation. Crushed by international intervention and political unrest almost two decades ago, a revived EAC provides those countries with international venues for settling political and economic disputes and developing cooperative approaches to development, rather than military intervention and other hostilities.

Completing those two significant projects required building hundreds of additional roads, bridges, electrification projects, and other physical structures that promote “economic connectivity.” Similar infrastructure projects in Congo, South Africa, Zambia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Mozambique, Angola, Chad, Cameroon, and Ethiopia produced similar results. Managed by Chinese state–owned enterprises (SOEs) operating on smaller profit margins than Western firms, those projects hired more local workers and supervisors than Western firms, successfully committed to schedules and projected costs better than Western firms, produced high-quality outcomes, and supported the transfer of technology and human capacity.

A third outcome, which is more difficult to quantify, is related to the issue of sovereignty. Between 2002 and the present, researchers have found that “African agency” has increased. In the China-Africa paradigm, countries have more room to make autonomous decisions. They have decided where infrastructure projects will be located and created new levels of cooperative relations with once rival, even hostile, nations. The China-Africa paradigm has opened new space for East African countries to secure their national interests.

African countries generally can use their elevated status in the China-Africa dynamic to secure better financial arrangements and shape the nature of Chinese investments. For example, researchers recommend that African countries negotiate for investments in building solar-power facilities (production and usage), make permanent medical facilities and universities (rather than simply missions), and enhance Chinese-African ties through enhanced technical and cultural training for African international students in China itself. African countries use vehicles such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation to accomplish these tasks.

What is “structural development economics”?

SDE is a concept coined by economist Justin Yifu Lin. Beijing-based Lin co-authored a study of the idea with Boston-based scholar Yan Wang titled Going Beyond Aid: Development Cooperation for Structural Transformation.

Their research is premised on the significant historical-geographical shifts in economic development. From Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries to North America in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and then to East Asia in the post-World War II era, Lin and Wang follow the trajectory of the most dynamic cases of development over the past three-plus centuries.

Important developmental pillars were planned and created in each situation: 1) a solid agricultural base, 2) an expanding infrastructure, 3) the transfer of modern agricultural and industrial capacity, and 4) attention to growing the technical and cultural capacity of the workforce (more so after the 19th-century interest in public education institutions).

In European and North American capitalist development, the European slave trade and the expropriation of Indigenous lands in the Americas were the foundation of the first two pillars. The Chinese concept of “structural development economics” sidesteps violent and genocidal primitive accumulation in favor of a people-centered political philosophy.

Lin and Wang say states and international institutions can achieve this through planning and deploying dynamic development processes in new places without imperialist goals or outcomes. State-led public-private partnerships can design infrastructure projects that uplift the unique resource advantages of a particular geographical space. These could be energy, mineral, or agricultural resources that establish a base for international trade and capital for industrial development. Industrialization is sparked by a shift in manufacturing centers from highly developed (China) to less developed countries.

In contrast with Western corporate outsourcing, the industrial offshoring in the SDE package is accompanied by improvements in technical capacity and labor development in the receiving country.

Western capitalist offshoring cared little for the social conditions of the receiving communities or the communities from which they moved. In U.S. contexts, capital flight was accompanied by neoliberal policies of diminishing social services. Motivated by a declining rate of profit, capitalists expected displaced U.S. workers to accept low-paid, nonunionized service-sector jobs. This structural de-development resulted in a massive erosion of public resources and living conditions in “rustbelt” centers.

In receiving countries, capitalist enterprises demanded government policies that eroded worker, ecological, and social welfare protections. They expected to profit from an even lower-paid workforce starving for job opportunities. Investments in offshore sites tend to remain isolated from the larger social development of the country in which those investments are made, producing limited structural transformation or only isolated pockets that promote more profound internal inequalities.

Africa in a new direction

Chinese policymakers see Africa as the next site of a major world-historic economic development.

Like the East African example, Chinese-backed infrastructure projects supported manufacturing investments in Mauritius, Tanzania, and Ghana in the early 2000s. These were followed by technology transfers, technical training, and educational programs, and by 2018 had resulted in “structural transformations in the industrial sector” in those countries.

Electrification projects in several countries such as DR Congo, Ghana, and other sub-Saharan African countries, along with considerable successes in railway projects in East Africa and Angola, are moving the needle on the relation between poor infrastructure and low growth rates. Thus, while much still has to be done, much has already been accomplished.

Structural transformation through infrastructure, economic connectivity, and industrialization (combined with technology transfers and human capacity improvements) within the China-Africa paradigm strongly contrasts with Western patterns. Instead of mining and petroleum extraction for export as raw resources, Chinese state–owned enterprises work with state-owned and private enterprises in African countries to manufacture finished goods. The research frequently discusses Chinese loans for jointly operated steelworks and cement works in Zimbabwe; Niger’s gas-producing oil refineries that produce for local consumption; oil refineries, cement makers, and telecoms in Chad; oil extraction and hydropower projects in the Republic of Congo; hydropower facilities and telecoms in Cameroon; and textile manufacturing centers in Benin and Tanzania. Such activities require technology transfers, training, high levels of local employment, and more complex local marketplaces.

One study of Chinese projects in developing countries concluded that infrastructure projects effectively oversaw significant spatial diffusion of economic activity to “reduce economic inequality within and between subnational localities.” Instead of injecting resources into isolated pockets of already successful enterprises, Chinese-originated resources diffuse to a larger scale of smaller enterprises that can then use newly built infrastructure to connect with local, national, regional, and international marketplaces.

Fears about “debt traps” can be alleviated if even more “connective” infrastructure is built that further erode the town-country contradiction and the isolating framework of Western-style aid. This model of structural development economics can work only if political nonintervention is prioritized. The diffusive benefit is restricted as soon as the lending entity decides who is most worthy to receive its aid.

Conclusions and directions

Structural development economics offers positive steps in a new direction that more closely meets the basic tenets of Rodney’s definitions of people-centered development. Autonomous political and economic decision-making, broader social and economic development that aims for equality within and between countries and regions, and enhanced technical and cultural development are key promises of that paradigm.

A realistic assessment of the overall record reveals more successes than failures. The most significant risk to success for the China-Africa independent development project lies with the dangers of U.S. imperialism. By conflating Africa with U.S. imperialism, U.S. officials are threatening to open numerous proxy wars on that continent via renewed military occupations, political interventions, and economic sanctions regimes that could derail the China-Africa paradigm and return the continent to some of the worst depredations of the neocolonial era.

The struggle to end expanding U.S. military involvement in Africa and to challenge distorted and hypocritical U.S. propaganda about the China-Africa paradigm is vital to derailing that imperialist agenda. Structural development economics allows developing countries to establish the foundations for social, political, economic, and cultural autonomy denied under neocolonialism and neo-imperialism.

For PDF versions of the cited sources, contact the author at jwendlandster@gmail.com.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

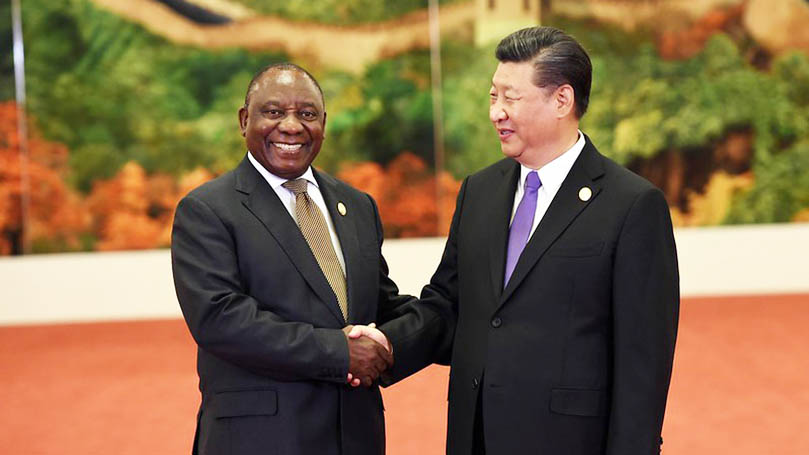

Images: President of South Africa Cyril Ramaphosa and President of People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping, Government ZA (CC BY-ND 2.0); AFRICOM general, , Wikimedia (public domain); AFRICOM’s Gen. Townsend, AFRICOM (website); Construction of Nairobi Expressway (China Daily); Protest against water privatization in Chile in 2013, Coordinadora por la Defensa del Agua y la Vida (Facebook); Railway in Kenya (China Daily); Construction site in Egypt (China Daily); Training at the Uganda Industrial Research Institute (China Daily).

Join Now

Join Now