The three pillars of American republicanism

“Bill of Rights Socialism” was first put forward by Gus Hall, Chairman of the Communist Party, USA, in his 1990 pamphlet The American Way to Bill of Rights Socialism. Emile Shaw wrote in 1996 that Bill of Rights Socialism “conveys the idea that we will incorporate U.S. traditions into the structure of socialism that the working class will create.” Since then, the CPUSA has continued to deepen and expand this theory to correspond with the real needs of struggle.

The CPUSA is not alone in this project; other communist parties have also been applying Marxism-Leninism creatively to produce important innovations, bringing socialist construction into the modern age while also adapting their own path to their unique national conditions.

How could it be otherwise? All struggles for socialism have unfolded within the context of their particular national circumstances. In Vietnam, it produced “Ho Chi Minh Thought.” In Cuba, the revolution linked itself to the legacy of Jose Martí. The many innovations in China are known as “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” No struggle has ever discounted their unique political traditions and general national conditions and been successful in achieving liberation.

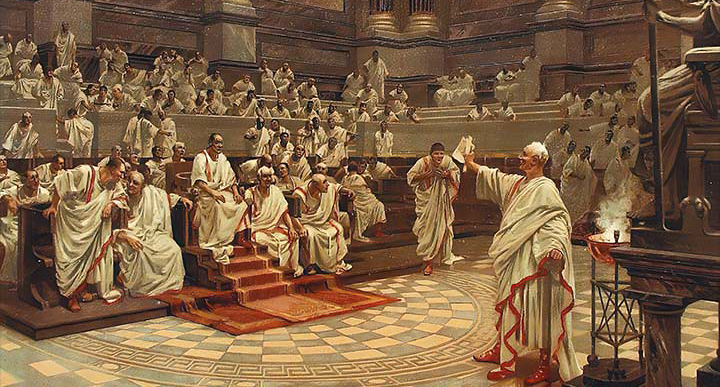

US republican traditions were deeply influenced by the Roman republic, where political sovereignty was derived from a free citizenry rather than a single monarch. According to Irish philosopher and world-renowned political theorist Philip Pettit, this centuries-old tradition of republicanism can be defined by “three core ideas” familiar to any US citizen:

The first idea, unsurprisingly, is that the equal freedom of its citizens, in particular their freedom as non-domination — the freedom that goes with not having to live under the potentially harmful power of another — is the primary concern of the state or republic. The second is that if the republic is to secure the freedom of its citizens then it must satisfy a range of constitutional constraints associated broadly with the mixed constitution. And the third idea is that if the citizens are to keep the republic to its proper business then they had better have the collective and individual virtue to track and contest public policies and initiatives: the price of liberty, in the old republican adage, is eternal vigilance.1

These “three core ideas” form the bedrock of the political tradition of the U.S. republic. Bill of Rights Socialism, then, must grapple with these three core ideas if we are to synthesize the revolutionary struggle of the working class with the unique political conditions of the United States.

Freedom and the republic

The ideological core of the U.S. is its emphasis on the concept of “freedom.” Anyone with even a passing familiarity of U.S. politics knows that every single other question revolves around this core ideal. No other single concept, even that of democracy, holds as much power as this idea. Pettit distinguishes two approaches to freedom: liberalism and republicanism, both of which were present at the birth of the United States.

Liberalism developed out of the European enlightenment period. It was a product of the rising bourgeoisie, which sought to guarantee freedom of commerce while leaving many other areas of domination untouched. Its basis is the freedom of the individual to own and dispose of property with a minimum of state interference.

Republican freedom is rooted in the Roman idea that to be free, a person must not suffer dominatio. This means that a free person must be free not only of active interference of political power but also inactive, latent interference by any outside force. Freedom is not only an act, but a status. The real enemy of freedom in the republican tradition is not just interference by political authorities; it is the arbitrary power that some people may have over others.2 Pettit elaborates: “[Freedom] means that you must not be exposed to a power of interference on the part of any others, even if they happen to like you and do not exercise that power against you.”3

Specifically, this means you are not free if you have a good boss or a good landlord who has the power to arbitrarily intervene against your employment or housing, but simply chooses not to do so. If that power exists, even in a latent and unexercised way, working-class people cannot be understood to have the status of freedom, since this “freedom” may arbitrarily change at any given moment. Working people under capitalism live in day-to-day dependence on the employing class.

Pettit articulates what he refers to as the “eyeball test” to help clarify what republican freedom means:

[Citizens] can look others in the eye without reason for the fear or deference that a power of interference might inspire; they can walk tall and assume the public status, objective and subjective, of being equal in this regard with the best. . . . The satisfaction of the test would mean for each person that others were unable, in the received phrase, to interfere at will and with impunity in their affairs.4

This definition of freedom should be intuitively familiar to all working-class people. Are you free if you have to pretend to be friends with your boss, bite your tongue, or fake your laughter to stay on the boss’s good side? When at-will employment prevails in so many workplaces, can working-class people be free if they can be fired for any reason or no reason at all? According to the republican definition of freedom, the answer is unequivocal: Working people are not free under capitalism.

Crucially, this means republicanism is distinct from the libertarian theory of freedom. Rather than being concerned exclusively with a vertical theory of freedom, where the state alone is seen as a threat to freedom, republicanism is also concerned with the arbitrary power private citizens can have over one another. Republican freedom means freedom not only from arbitrary state interference, but also from abusive partners, racial and national discrimination, and the private tyrannies of modern capitalism. Republican freedom has always meant more than just free markets.

Bill of Rights Socialism, then, recognizes the inherent contradiction of “freedom” in monopoly capitalism — it is a smokescreen for the objective increase of unfreedom for the sake of profit. In today’s stage of capitalist development, the objective condition of most of U.S. society and the broader world is to be unfree and dominated by finance monopoly capitalism and imperialism. Second, Bill of Rights Socialism asserts that this contradiction can be resolved only by putting an end to the dictatorship of monopoly capital through a popular, democratic revolution that elevates the working class to the leading, decisive social element constituting state power.

The mixed constitution as a class balancing act

The second “core idea” of republicanism is the “range of constitutional constraints associated broadly with the mixed constitution.” This tradition of the “mixed constitution” (mixed government) developed out of revolutionary class struggle as a way to balance the contradiction between the general “human” struggle for emancipation and the particular class project upon which the new state must be founded.

The most well-known republic in ancient history was formed in Rome with the overthrow of the Roman monarch Lucius Tarquinius Superbus by the patrician aristocracy of Rome. Tarquinius’ rule had become so intolerable to the aristocracy that they resolved by degrees to overthrow him.

Yet the patricians by themselves could not bring to bear enough force to decisively win in their revolutionary struggle. The revolution was sparked when the masses of plebians rioted over the rape of Lucretius by Tarquinius’ son and her subsequent suicide. This mass activity was critical for the aristocracy to unite and banish the monarchy and replace it with two consuls who would be able to “check” one another through a veto.

The mixed constitutions of republics emerged out of this historical process as the institutionalization of a balanced form of class rule. The Roman aristocracy was able to secure its position of power in the Roman Senate. Yet spontaneous plebian activity in the revolutionary struggle forced the patricians to integrate the popular class into its republican system as well. Checks and balances in a republic are reflections of the underlying balance of class forces at a particular moment when that republic is first constituted.

Machiavelli makes this observation explicitly in his Discourses on Livy:

I say that those who condemn the dissensions between the nobility and the people seem to me to be finding fault with what as a first course kept Rome free, and to be considering quarrels and the noise that resulted from these dissensions rather than the good effects they brought about, they are not considering that in every republic there are two opposed factions, that of the people and that of the rich, and that all laws made in favor of liberty result from their discord.5

According to political scientist Kent Brudney, Machiavelli “accepted the class basis of political life and believed that class conflict could be beneficial to a republic.” The “creative possibilities of class conflict” were recognized for “their importance to the maintenance of Roman liberty.” Brudney continues: “The episodes of conflict between the Roman patriciate and the Roman people were vital to the development of good laws and to the continuity of Rome’s founding principles.”6

This class-struggle understanding of mixed constitutionalism was also at the fore in the debates around the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Scholar James Wallner directly connects the debates around the creation of the Senate with Machiavelli’s theory of institutionalized class struggle:

The U.S. Senate exists for one overriding reason: to check the popularly elected U.S. House of Representatives. Throughout the summer of 1787, James Madison and his fellow delegates to the Federal Convention highlight, again and again, the Machiavellian observation that institutionalized conflict was essential to the preservation of the republic. Trying to inject an updated understanding of Machiavelli’s dictum into the heart of the new federal government, they created a Senate whose institutional features — size, membership-selection process, nature of representation, length of term of office, compensation — are properly understood only in relation to the body’s House checking role.7

Wallner points to Federalist Paper No. 62, where James Madison wrote: “The necessity of a senate is not less indicated by the propensity of all single and numerous assemblies to yield to the impulse of sudden and violent passions, and to be seduced by factious leaders into intemperate and pernicious resolutions.”

Wallner points to Federalist Paper No. 62, where James Madison wrote: “The necessity of a senate is not less indicated by the propensity of all single and numerous assemblies to yield to the impulse of sudden and violent passions, and to be seduced by factious leaders into intemperate and pernicious resolutions.”

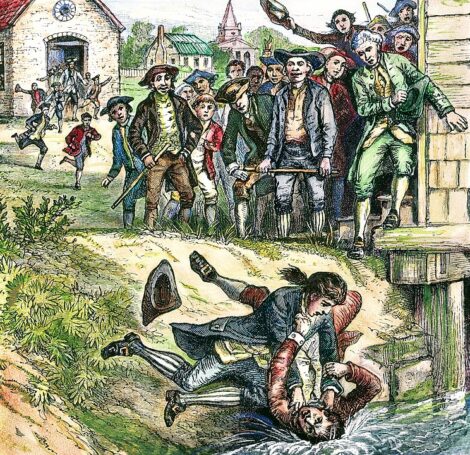

The recent Shay’s Rebellion had been sparked by Massachusetts farmers demanding debt relief that was opposed by the merchant class that dominated the state government. This rebellion pressed the Federalist framers to consider the inclusion of an “aristocratic” senate capable of effectively subduing the “violent passions” of the masses, something missing from the Articles of Confederation that had preceded it.8

Thus, we see that “mixed constitutions” of republics are only the institutionalization of class struggle. If the republic is supposed to make the affairs of public power a question of public input, it must always balance the class foundation of the state with at least the nominal political participation of the masses. Ruling class power in a republic is always concentrated in the senate, and popular power is always located in a “lower” branch of government. This balance creates a dynamism between the two while also developing a hegemonic understanding of the state as representing “the whole people,” even if the state is always constituted under a specific class basis.

Bill of Rights Socialism deepens the theory of the mixed constitution and gives it a proletarian character. Rather than calling for the abolition of the senate as such, Bill of Rights Socialism recognizes the need to reconstitute the republic along proletarian class lines, transforming the current senate founded on the “wisdom” of slave owners and oligarchs into an “industrial” senate that is instead based on the wisdom and experience of the leaders of the working class.

Like Lenin’s soviets, the industrial senate would be built out of “the direct organisation of the working and exploited people themselves, which helps them to organise and administer their own state in every possible way.” Leaders, drawn from the broad working-class majority, would carry with them both an intimate knowledge of all parts of the production process and a distinct working-class perspective into the development of public policy. And like both the soviets and senates past, the industrial senate would be insulated from universal direct election, with a focus on cultivating tested working-class leadership collaborating to build and protect a common vision of a democratic socialist republic. The class character of the senate would serve as a “check” on one side of the equation.9

But Bill of Rights Socialism can grow only out of the success of a massive people’s front. Led by the organized working class, this front would also contain all progressive people and class allies, including small farmers, small- and medium-size-business owners, the self-employed, and independent intellectuals and professionals. The primary stage of socialism does not end class struggle but transforms it under the decisive political rule of the working class. A “People’s House” would provide a democratic space for these other class elements to make constructive and progressive contributions to building socialism without sacrificing or obscuring the working-class nature of the new republic.

Further, experience from the last century indicates that even a working-class state can degenerate bureaucratically without broader popular participation and oversight. In addition to incorporating non-proletarian class elements constructively into the workers’ republic, the lower house would also provide a space for the exercise of universal suffrage and the direct election of representatives by the whole people. These popular representatives could play a consultative role to the industrial senate and provide institutional oversight. This would provide a “check” on the other side of the equation.

The “checks and balances” between the industrial senate and the people’s house would capture the “quarrels and the noise” familiar to American democracy while preserving absolutely the republic’s fundamental class nature. This dynamic interrelationship creates the conditions for the third core idea of republicanism to prevail, the “contestatory citizenry.”

It is right to rebel (within limits)

The third core idea of republicanism depends on the active engagement of its citizens “to track and contest public policies and initiatives.” Freedom can be secured only through struggle. This ideal has been a fundamental political principle of all oppressed people struggling for their democratic rights and freedom in the United States. Frederick Douglass taught us years ago the price of freedom:

If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.10

The contestatory citizenry forms a fundamental basis for the Bill of Rights and so must serve as a basis for Bill of Rights Socialism. These rights include freedom of speech, of assembly, of faith and conscience, and the right to be informed about the functioning of public power. Politically critical art, protests, and organizations must play a fundamental role in the construction of socialism in the United States and thus must be protected under Bill of Rights Socialism.

Struggle does not only occur between oppressor and oppressed, between exploiter and exploited. Struggle also goes on within the oppressed and exploited. Historical development has created an unevenness within the working class: divisions around race, sex, sexuality, religion, cultural beliefs, nationality, language, and so on. This unevenness can be overcome only after a long period of struggle to resolve these divisions and build a unity through our diversity; to give real content to the national motto “E Pluribus Unum.” While the initial steps in this process of internal struggle for unity within the working class and democratic forces must be made before the establishment of socialism by building a people’s front, the establishment of socialism does not mechanically erase the social unevenness within that people’s front overnight.

Revolution and reform are distinct, but also deeply interrelated. The development of social scientific methods and professional specialization has produced the historical capacity to carry out deep and broad reforms to the social system in a planned, scientific, and rational way. Reform can and must always go on, improving social institutions and making sure they advance with the times. However, reform does not happen abstractly, but according to the degree of political will brought to bear on the process. Reform in a social system hits a wall when the ruling class is no longer willing to exercise its political will to allow the reform process to deepen and expand according to the needs of the populace.

Revolution is not in and of itself the solution to social problems; revolution is the punctuated transformation from one form of class rule to the next. This transformation in class rule does not replace reform, but unlocks it to unfold more deeply, at a faster pace, and in a more thoroughgoing way than the degenerate ruling class that was replaced could or would allow. By elevating the working class to the level of the ruling class in a workers’ republic, the struggle for reforms is not ended but transformed. Republicanism allows this reform struggle to take place both on an individual, contestatory foundation protected by a socialist Bill of Rights, as well as within the bounds of law constrained by socialist constitutional forms.

Peace, prosperity, democracy, and freedom

Let us be crystal clear: the United States needs a socialist revolution. The old ruling class, dominated by finance monopoly capital and incapable of keeping pace with the needs of the time, must be overthrown and in its place the working class, at the head of a mass democratic movement of all oppressed people and classes, must be elevated to rule in its place. The class basis of the current republic must not be ignored but instead placed at the center of the conversation.

But the struggle is not to “abolish” the republican form outright. There are no serious ideas, to be perfectly frank, on what to put in its place. The soviet system was for the Soviets, the Chinese system for the Chinese, so on.

The struggle is to revolutionize the republic to preserve the republican system at a higher level of development. Indeed, the fundamental argument of Bill of Rights Socialism must be that only a socialist revolution can preserve the republican liberties and democratic rights that so many oppressed and exploited people have fought hard and made tremendous sacrifices to secure. Socialist revolution means the deepening of democracy under the decisive state leadership of the working class.

This essay is only a theoretical sketch to show the consistency between Marxism-Leninism and the “core ideas” of the republican political tradition. There are an almost limitless number of questions that arise from its premise: Can a workers’ republic be secured through the amendment process or through a new Constitutional Convention? How exactly should an industrial senate be ordered and secured? Should it be through indirect election, sortition (selection by lottery), selection, or a combination? How does federalism fit into this picture? How can we more explicitly articulate its relationship to imperialism and oppressed nations? And many more.

Only through thoughtful struggle — not isolated contemplation or outrageous sloganeering — can the political soil be tilled to allow new possibilities to develop. Bill of Rights Socialism is not an “answer” in itself but a path to be blazed by combining the creative leadership of the Communist Party with the limitless dynamism and transformative potential of millions of Americans from all backgrounds linked together in the struggle for peace, prosperity, democracy, and republican freedom.

Sources

- Philip Pettit, “Three Core Ideas,” On the People’s Terms: A Republican Theory and Model of Democracy, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 5.

- Philip Pettit, “The Communitarian Opposition,” On the People’s Terms, p. 11.

- Pettit, “Three Core Ideas,” p. 7.

- Pettit, “Social Justice and Equality,” On the People’s Terms, p. 84.

- Kent M. Brudney, “II. Machiavelli on Social Class and Class Conflict,” Political Theory, vol. 12, no. 4, 1984, pp. 507–519., doi:10.1177/0090591784012004003.

- Ibid.

- James Wallner, “Real Purpose of the Senate: To Check the Actions of the House,” LegBranch, R Street Institute, 5 Dec. 2018, www.legbranch.org/real-

purpose-of-the-senate-to- check-the-actions-of-the- house/. - Ibid.

- Vladimir Lenin, “The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky,” PRRK: Bourgeois and Proletarian Democracy, Marxists.org.

- Frederick Douglass, “(1857) Frederick Douglass, ‘If There Is No Struggle, There Is No Progress,’” BlackPast, 8 Aug. 2019.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: Top, Thomas Dwyer (CC BY-NC 2.0); Eviction, Bart Everson (CC BY 2.0); Roman Senate, Mary Harrsch, Creative Commons, Public Domain; Shay’s Rebellion, Wmpetro, Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0); Power to the People, Saundi Wilson (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Join Now

Join Now