Once upon a time, and sadly, not so long ago in the grand scheme of history, a young high schooler in Virginia spent his summer, the summer of 1964, watching the Civil Rights Movement play out before his eyes. Little did this student, Scott Marshall, know how life-changing that first Freedom Summer would turn out to be for him and the country as a whole.

As the June heat took over Mississippi that year, three young Civil Rights activists, volunteering to register Black voters in the South, were murdered by the local Ku Klux Klan. Black Americans had been barred from voting since the turn of the century, courtesy of Jim Crow laws and the KKK, and local politicians and law enforcement wanted to keep it that way—at any cost. That ire, that hate, led them to run down, shoot, and bury those young volunteers in pre-planned graves.

“That hit me like a ton of bricks,” Marshall told People’s World in a recent interview. “I just could not believe that people would be murdered for registering people to vote and trying to change things for the better. . . . It got me amped up.”

That moment in ’64 led to a committed determination “to do something.”

Two years later, the summer between his junior and senior year, Marshall, now a newly minted activist, took part in the Freedom Summer voter registration campaign himself, volunteering in southern Virginia. He experienced not just the KKK’s brand of “justice” but also a subtle awakening of class consciousness. It was only natural, in the traditional vein of radical progressivism, for him to join the Southern Student Organizing Committee, which was then followed by his next “job”: earning five dollars a week to help organize local boycotts as part of the United Farm Workers’ Delano grape strike.

“When Gus Hall, general secretary of the Communist Party USA, came to speak at the University of Virginia, I was invited to go . . . but, I missed out because the Grateful Dead was playing the same night, and I decided to go see them instead. I still kick myself over that.”

As he watched the counter-culture sixties transform into the militant rank-and-file seventies and eighties, he also tucked a union card and CPUSA membership card into his wallet. And there they would stay.

“What led you to join the Communist Party?” I asked.

“Someone heard me talking about politics and social justice issues and said, ‘You sound like a communist . . . that’s not a bad thing,’ and it just took off from there.”

An off-the-cuff comment and lived experience would be the driving force behind a life dedicated to the struggle.

Fightin’ in the eighties

Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, industrial automation, and Gordon Gekko’s Wall Street mantra, “Greed is good,” defined the eighties. As America experienced socio-economic changes in leaps and bounds—tech booms, globalization, trickle-down economics—avarice took hold at the highest levels of political and corporate power.

Rank-and-file workers in the previous decade, coming off the McCarthy era that had decimated labor’s radical left, were embroiled in fights nationwide to reclaim their unions from business-minded right-wing officials. In the steel industry, the “steelworkers’ fightback” organized and pushed for democratic reforms locally and nationally within the United Steel Workers of America union. Their fight was the genesis of what would become the unemployment movement of the eighties and the JOIN campaign (Jobs or Income Now).

“The unemployed movement came out of the rank-and-file surge that came out in the ’70s, away from business unionism. A lot of people had the wrong narrative, that workers were too rich, too spoiled,” said Marshall. “The real reason was the decimation of the left coming out of the McCarthy period. When the left was removed from the labor movement, it left the most pro-business union bureaucracy and the right-wing forces in charge.”

In 1980, Marshall was faced with the closure of the Pullman Car Company plant where he worked at the time.

“Pullman in those days made passenger cars for Amtrak; we built a whole line of trains for Amtrak and also made cars for New York’s subways,” said Marshall. “The big irony of the shutdown was that Pullman decided to pull out of making mass transit equipment—a huge mistake—and decided they could make more money in the oil industry by building ocean drilling platforms.

“You can add in automation as part of the reason for mass layoffs in industry . . . more and more plants needed fewer workers. Of course, corporations took off from there and began shipping jobs to other countries where they wouldn’t have to deal with labor laws or safety regulations.”

Despite the rapid rise in the use of mass transit, the plant closure was slated to go ahead. The anger among the workers was palpable, and there was no way members of USW Local 1834 would go quietly. Marshall found himself elected as co-chair of the local’s “Save Our Jobs Committee.”

“Reaching out and contacting others is important. When we started, we thought we were unique—the only ones fighting against plant closings. We’re not. Other save our jobs committees have sprung up across the country,” Marshall said during an interview with the Daily World on July 31, 1980.

“Plant closings are a national phenomenon, there is a need for a national link-up of groups fighting for the same thing to coordinate our efforts.”

Who else had “Save Our Jobs Committees?”

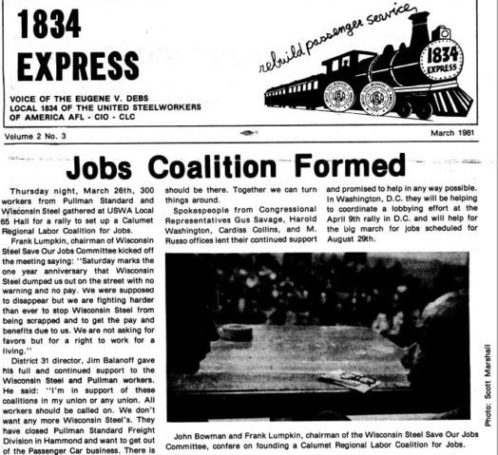

Most notable was the Wisconsin Steel SOJ Committee led by Frank Lumpkin in Chicago. With the abrupt shutdown of Wisconsin Steel’s South Side plant in March 1980, Lumpkin and everyone else at the plant found themselves out of work, denied their pensions and even their last paychecks. The scene was to be repeated often in the coming years at plants across Chicago’s industrial South Side.

By 1981, Marshall’s union local, USW Local 1834, was busy on the picket lines, upping the pressure on elected officials who had voted down a mass transit bill that would have seen an increase in federal funds for public transportation and, as Marshall calmly put it while on the picket line 1981, “They just sent $25 million to El Salvador for military arms . . . that would build 25 more cars and keep us working for three more months.”

It’s at this point in our story that talking began, the seeds of mass action and movement planted.

“Jobs Or Income Now started with people just talking to each other,” Marshall said. “The Wisconsin Steel people, U.S. Steel’s South Works people, and Pullman people—a lot of us were CPUSA, and we just began reaching out to some other folks.

“It was the purest of things—fighting to save jobs for one—that happened before we all got together as a group. We were all fighting for the same thing, and when we realized it, we decided to work together.”

Funny how today, as radical politics sees a reemergence on the public scene, folks seem to have this idea that political ideology alone drives action rather than lived experience. Yet so much of our radical history is created by those who took their lived experience into the fight for justice before ever picking up the politics.

A new organization is born

In June 1981, a new organization was born with the name Jobs Or Income Now, as over 13,000 steelworkers found themselves standing, hard hat in hand, at the unemployment office.

“We didn’t make this mess (unemployment), why should we suffer for it?” Marshall asked fellow workers at JOIN’s founding conference. He was elected co-chair, along with Rev. Hosea Ivey, who represented the U.S. Steel South Works plant. From far in the back, one unemployed steelworker attending the conference said, “We need to build JOIN just like a union of the unemployed.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Millions today are again facing sudden unemployment—along with a possible economic depression caused by the global pandemic.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Millions today are again facing sudden unemployment—along with a possible economic depression caused by the global pandemic.

JOIN’s demands in 1981 were simple: Long-term unemployment benefits for displaced workers; jobs programs, with a focus on creating jobs in Black and Hispanic communities (still the hardest hit by downturns); no evictions of the unemployed; no utility shutoffs; and federally guaranteed medical insurance for the unemployed.

Besides organizing the unemployed, JOIN was busy “starting a petition campaign to extend unemployment benefits for steelworkers under the Trade Act of 1974, which was up for renewal,” explained Marshall. Trade Readjustment benefits (TRA) were intended to give American workers financial relief if they were negatively affected by international trade.

“JOIN got involved in fighting for TRA, in addition to our other petitions, like week to week paycheck unemployment benefits,” Marshall continued. “And at that time, we were also organizing to get state legislation passed to extend unemployment benefits. Me, along with Frank (Lumpkin) were busy turning in petition after petition until finally, we decided to up the stakes.

“Sen. Charles Percy, a moderate Republican with a pro-labor record, sometimes, was who we decided to approach about introducing the legislation. We got to his office and were told he wasn’t there, that he was in Washington, D.C. So, all 20 of us there asked to get him on the phone. When we were inevitably told that couldn’t be done, we said, ‘Ok, we’ll wait,’ and staged a sit-in. And guess what? We got him on the phone, and he said he would introduce the bill.”

On Aug. 12, 1982, Percy, joined by Sens. Metzenbaum and Dole, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, moved an amendment to the budget reconciliation bill extending unemployment benefits through March 1983 to all states and adding 10 to 13 extra weeks to the extended benefits program. It passed the Senate by a vote of 84 to 13.

As the eighties pushed ahead, chapter after chapter of JOIN was formed, direct action increased around fighting housing evictions for the unemployed, and efforts were continued to improve unemployment benefits and jobs programs.

“As we face similar dire conditions today, what advice would you give to this new generation of activists?” I asked.

“To concentrate on building a mass movement with gig workers or any other groups fighting to organize for improved labor rights and protections,” Marshall says. “And there are all kinds of ways we could help support that, and to just get involved in the struggle.”

He also encourages everyone who gets involved “to always keep in mind time, place, and circumstance.” He says that while “we can learn a lot of history, our real organizing has to be on the conditions happening right now.” Helpful lessons can be learned, but “past experience can’t be an exact blueprint.”

This article was published by the People’s World on May 15, 2020.

Join Now

Join Now