“It is entirely wrong, therefore, to do as the economists do, namely, as soon as the contradictions in the monetary system emerge into view, to focus only on the end results without the process which mediates them” (The Grundrisse, “Money”).

Many young people in the U.S. are hearing about inflation for the first time and wondering what it means for them. Perhaps they’ve heard about the hyperinflation in Venezuela caused by U.S. sanctions, with piles of money being used to buy a cafecito. Perhaps they’ve heard of the hyperinflationary struggles in Zimbabwe, also caused by sanctions, where bank notes were printed in denominations of trillions up until recently. The idea of watching the value of one’s money drop in value, especially to these levels, seems intimidating to those of us with not much in our bank accounts to begin with. Because we are living in exceptional times, brought on by a disastrously managed Covid-19 pandemic, it’s important for us to gain solid understanding of what inflation is before we’re informed whether or not it’s bad on CNN or Fox News.

Most people understand inflation thus: the money in my pocket will buy less tomorrow than it can buy today. It is also known as an average increase in the prices of goods. Indeed, as the U.S. market has operated in the past decades, a nominal amount of inflation is normal — around 2–3% per year. This is why people with enough money to save are generally encouraged to invest it in order to maintain its value. Putting money into an interest-bearing bank account (where the bank loans the money out at interest and pays you a portion of it) used to be the simplest way to save, though interest rates on savings accounts have bottomed out since the 2008 financial crisis. The highest interest rates on such accounts don’t exceed 0.5% — certainly not enough to keep up with 2% inflation. When inflation rises, saving is discouraged because, again, the money in your pocket will buy less tomorrow than it will today.

But how many people are really worried about their savings in this environment? Less than 40% of workers in the U.S. can pay $1,000 in case of an emergency. A 2020 report issued by the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that no worker making minimum wage in the U.S. can afford a one-bedroom apartment. In New York, where 46% of households rent their dwellings, workers would need to bring home $32.53 per hour to afford a two-bedroom apartment. The mean wage of renters in New York is $25.68, meaning that in a two-income household, at least one of the two workers are working purely to pay rent — and even then, a third of the second worker’s wages will go to rent as well. The costs of housing, education, and medical care have risen significantly over the past decades. More and more are taking on debt to keep up with living expenses.

The idea that most workers in the U.S. are able to not just save but also invest money is difficult to imagine. The majority of savings, when they exist, are wrapped up in pension funds or other types of retirement accounts. Most young workers are likely to have more debt than savings. The average person in the U.S. has more than $90,000 in consumer debt, and the student debt market will soon cross $2 trillion in scope.

Why then, is inflation weighing so heavily on the minds of mainstream economists?

As part of the pandemic response, the U.S. government decided to flood the economy with money, whether through issuing direct payments of a few thousand dollars to families or giving many millions to employers to cover payroll and avoid mass layoffs. Unemployment insurance was generously supplemented with federal money. As a result, the amount of money in circulation increased significantly, with almost 25% of all money currently in circulation being added last year.

For most workers, this was a life-changing event. Unemployed workers in Florida went from collecting $270 per week in benefits to $820 overnight. With a median national wage of about $34,000, many workers had more money during the pandemic than ever before. Wages began to rise because workers were no longer as firmly coerced to accept poverty wages and bad jobs.

Cue the panic as major corporations like McDonalds and Walgreens faced a labor crunch of epic proportions. Nobody wanted to risk their lives by taking a pay cut to work at Hardees. Even Joe Biden said that the solution would be to raise wages, but in Republican-led states such as South Carolina and Florida, governors have already begun to slash unemployment benefits in hopes that the threat of starvation will push workers back into bad jobs with bad wages.

In some circles, inflation is sometimes described as “deferred class conflict.” Even in the post-industrial service-oriented United States, workers still hold all the cards. If they don’t go to work, Jeff Bezos doesn’t get paid, and the economy grinds to a halt. In the event of a mass crisis such as a global pandemic, this balance of power becomes crystal clear. Companies are forced to raise wages because workers do not need them as much or are unwilling to risk their and their families’ safety to obtain them. Capitalists pay out higher labor costs because they are forced to. Their profits begin to suffer, and to avoid going out of business, they’re forced to seek profits elsewhere.

In some circles, inflation is sometimes described as “deferred class conflict.” Even in the post-industrial service-oriented United States, workers still hold all the cards. If they don’t go to work, Jeff Bezos doesn’t get paid, and the economy grinds to a halt. In the event of a mass crisis such as a global pandemic, this balance of power becomes crystal clear. Companies are forced to raise wages because workers do not need them as much or are unwilling to risk their and their families’ safety to obtain them. Capitalists pay out higher labor costs because they are forced to. Their profits begin to suffer, and to avoid going out of business, they’re forced to seek profits elsewhere.

In some circumstances, this will translate to an increase in prices. Think of a small business owner who owns a sandwich shop. Suddenly forced to pay 25% in higher wages to their workers to discourage them from quitting, they decide to recoup their labor costs (and supplement their profit) by raising the price on each sandwich by 10%. They figure that since workers on average seem to have more money in their pockets, they can get away with raising prices and still selling the same number of sandwiches. For the workers who received a 25% raise, this price increase is tolerable. If not, then they will not buy the sandwich and the business owner will be forced to lower prices.

It’s important to note that this increase in wages and price (inflation) is not simply due to market forces. The state has a significant role to play, as it encouraged higher wages by putting more money in the pockets of workers, and in the pockets of the business owner as well. Higher wages can also be a result of higher rates of organized labor protected by both a union and a legal system that recognizes and protects unions. The state is an important part of any class system and plays a critical role when markets break down. Left to its own devices, the market forces of capital might have evicted millions unable to pay their rent at the height of pandemic, causing mass unrest that could have agitated the uprisings against the police seen last summer. Capitalists are a class of their own, but they do not generally act in their best interest as a whole. Indeed, under the market laws of competition, they must do what’s best to secure as much profit as possible at the expense of other profit seekers, even if that means destroying the planet, among other things. A state beholden to capitalist interests will do what needs to be done to protect the capitalist class from itself, whether that means issuing bailouts, stimulus checks, or proclaiming a moratorium on evictions. Individual capitalists might chafe under this intervention, but without it, capitalism as we know it might have collapsed for good last year.

Inflation means that the money in my pocket might be worth less tomorrow than it is today. It also means that the money I owe a bank on my credit cards or student loans tomorrow is worth less than it is today. Let’s say that my total outstanding debt is $100,000. If annual inflation rises from 2% to 10%, I will functionally owe 10% less on my loans next year than I do this year. Classical economists will complain that higher rates of inflation make it harder for my generation to plan for the future — yet we millennials have long said that we don’t feel like there’s much of a future for us anyway.

In the Grundrisse, Marx begins with a close examination of money. It is the expression of exchange value (price), a unit of account, as well as a store of value. It is also “the power which each individual exercises over the activity of others or over social wealth exists in him as the owner . . . of money” (Notebook 1). It is “the means of life for the individual” because it is that special thing, what Marx considered the god of all commodities: “No commodity expresses the price of money, because none expresses its relation to all other commodities, its general exchange value” (Notebooks 1/2). After primitive accumulation and enclosure, we workers now use money to obtain nearly everything we need to live.

In the Grundrisse, Marx begins with a close examination of money. It is the expression of exchange value (price), a unit of account, as well as a store of value. It is also “the power which each individual exercises over the activity of others or over social wealth exists in him as the owner . . . of money” (Notebook 1). It is “the means of life for the individual” because it is that special thing, what Marx considered the god of all commodities: “No commodity expresses the price of money, because none expresses its relation to all other commodities, its general exchange value” (Notebooks 1/2). After primitive accumulation and enclosure, we workers now use money to obtain nearly everything we need to live.

But if money is both the realization of value and a way for the individual to carry “his social power, as well as his bond with society, in his pocket” then what happens when workers have more of it? Does the money itself somehow make life easier for the worker? Economists who are against the minimum wage will argue that if the floor on wages were raised to say, $15 an hour, prices would rise to recoup not only profit but also that lost social power. This is why simply putting more money in the pockets of the working class as a whole cannot accomplish what we see money obtain on an individual basis — secure housing, education, healthcare, and free time.

If a worker needs to earn at least $85,000 per year to obtain these things, then to simply give every worker that amount of money would result in either a rise in prices or in the destruction of a system that affords a select few individuals comfort at the expense of the working class. As Marx explains, “A particular individual may by chance get on top of these relations, but the mass of those under their rule cannot, since their mere existence expresses subordination, the necessary subordination of the mass of individuals” under capitalism.

It is a good thing that workers presently realize — if subconsciously — that we have the leverage necessary to demand higher wages, but we cannot nickel and dime ourselves. Prices and wages can be discussed as abstract concepts, but they also have real impacts on our day-to-day lives. More money in our pockets is meaningless without the ability to use that money to buy what we need. If we leave housing, healthcare, education, and other necessities to the mercy of monopoly capital, the working class as a whole will never have enough money to equitably secure these things. Labor is the creator of all value. Thinking of money as the true expression of the value we collectively produce inevitably depreciates our power as a class and deepens our alienation. Workers build power not by earning more money as individuals, but through collectively bargaining for a better future as a class.

Perhaps you’re wondering how all of this is supposed to answer our initial question about inflation. Let’s return to the talking heads on TV, who are scaremongering with their talk of inflation.

Let’s recall the last time that inflation was such a hot topic — the dawn of globalization.

During the so-called labor peace that existed during the Cold War, when Keynesian policies sought to save capitalism by coercing bosses to hand over a bigger piece of profit to their workers and thereby avoid socialism, workers in the U.S. had more access to what they needed to live. This was the heyday of organized labor in the U.S. As the Soviet Union began to wane and the Cold War began to come to a close, capitalists started raising prices to recapture the profits they’d been forced to give up in the decades prior. Double-digit inflation followed. Inflation became the bane of mainstream economists, who insisted that to continue would wipe out all gains made in the previous decades. When the state had a choice to make — workers or business? — the choice was clear.

Monetary policies set forth by Paul Volcker in 1980 raised interest rates, pushing the developing nations deep into debt peonage and the working class in the U.S. into unemployment and a declining standard of living. Full employment, once a goal of economic policy, was now considered undesirable among those in power. A relatively stable percentage of unemployed workers would provide something called “labor flexibility.” If someone was unemployed and willing to do the job for less than your current wage, workers would be discouraged from asking for a raise, much less a union. Debt peonage forced countries to open their markets to capitalists from halfway across the world who were eager to sop up their lost profits through the hyper-exploitation of third world labor. Unions that tried to bargain saw factories shut down, dismantled, and moved elsewhere. Laws were passed to weaken unions. Consumer debt began to grow. The prison-industrial complex began to bloom, warehousing millions of disproportionately Black and brown workers, to provide the ultimate reserve army of labor. States passed laws gutting what was left of the social safety net. If labor’s progress was sparked by the October revolution in 1917, here then was the vicious counterrevolution in all its horror, again “dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt” (Capital). While billions worldwide were worse off for it, the rate of inflation indeed declined.

There are really only two ways out of this pandemic crisis, and much of it comes down to whether the state will be pressured by material conditions to favor either labor or capital in the rebuilding effort.

Joe Biden’s Democratic Party has proposed a sweeping infrastructure investment, sorely needed for decades. The bill aims to repair 20,000 miles of badly failing roadways, upgrade airports, fix 10,000 bridges, eliminate lead pipes in water systems, and deliver high-speed internet to all. It will upgrade and enhance existing public transport networks. It will build a green energy sector, upgrading what already exists while capping what is harmful and no longer used. It is also a jobs plan, where the federal government will play a role in setting industry sector wages, benefits, and worksite conditions. Importantly, it will also encourage unionization of these workers through the PRO Act.

In addition to this infrastructure push, the Biden White House has also announced the American Families Plan, which will create free pre-K and community college for all. It will also expand tax benefits for families with children, provide up to 12 weeks of paid family leave, and subsidize childcare by capping costs at 7% of wages for middle- and low-income families. Whether this agenda will be accomplished depends on a number of criteria. One of the most important, of course, is whether the people and their working-class institutions demand it.

Public opinion must be shaped, and so, the familiar refrain becomes: how are we going to pay for it? The answer is to force the wealthy to pay their taxes and, if needed, print whatever else needs printing. And so here comes the latest buzz on inflation. But now, according to these scaremongers on TV, it’s supposed to be this thing called inflation that’s the real concern for the working class, not childcare, crumbling bridges, lead pipes, dried-up wages, sick leave, destitution, debt, and global warming. The right-wing builds preemptive counterrevolution by making it seem as though the economy is simply a button to push here and a lever to pull there as opposed to being everything around us, including the most intimate details of our everyday lives.

Inflation is not our problem. It’s a problem for the banks, capitalists, and wealthy, but not for those of us who can hardly imagine ever having something like a retirement account. Capitalism was already coming up on another massive crisis before the Covid-19 pandemic. We could already see it in the disconnect between increasing prices and declining wages. We could see it developing alongside the increased effects of global warming. Capital wants to push us back into low-wage work to realize its profits. Capital’s representatives both in business and government will try all sorts of tricks to slash the meager safety net tossed out by the state in an attempt to quell last year’s unrest. There is a preemptive counterrevolution brewing from the right, even if it comes laced with concern about monetary policies most workers have never heard about, much less understand.

Marx began his Grundrisse by discussing money — not the commodity — perhaps because he himself was poor and understood too well its nature as “the means of life for the individual” under capitalism. It’s important to demystify what money is and what it means in order for us to push harder for what we really need: housing, healthcare, education, and all those other things money is supposed to buy for us as individuals, but that we’ll never have enough as a subjugated working class to obtain.

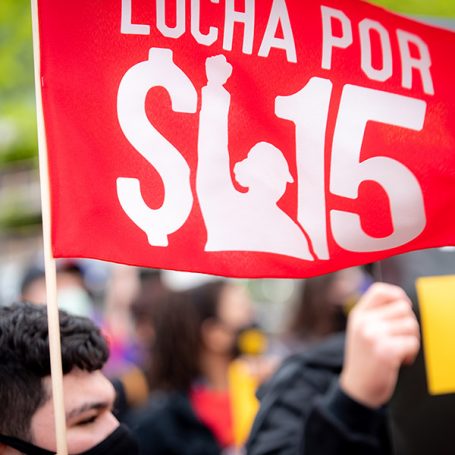

Images: Building Justice, SEIU (Facebook); Rent protest, Informed Images (CC BY-NC 2.0); Lucha por $15, D15 (Facebook); Empty pockets, Dan Moyle (CC BY 2.0); Union sign, SEIU (Facebook); Solar panel built with union labor, IBEW Local 59 (Facebook).

Join Now

Join Now