On a cool, tropical morning in the tumultuous year of 1931, the American poet Langston Hughes woke up snugly and confusedly on the inside of a large clay drainage pipe. The pipe, his home for the previous night, was one of a series of large pipes that sat estranged on the side of a mountainous road somewhere in rural Haiti, perhaps to later be placed under roads to drain the overflowing streams that flood under the weight of violent storms with their heavy rains. But at this moment they remained underutilized in the applied field of water redistribution and instead became a source of warmth for the poet whose bus had run out of gas the night before.

At this moment in time, the 29-year-old poet faced an uncertain future — he was relatively well-known in literary circles but was in no way famous; he was consistently winning literary prizes but was in no way rich; well-endowed with inspiration, yet destitute of financial stability. That he made it this far was impressive enough, considering the overwhelming odds against him as a working-class Black man in America, but despite it all, he went on to establish himself as one of the most celebrated poets of the 20th century.

In his childhood, Langston Hughes lived a volatile life, his father left behind the family and the unbearable racism of America for Mexico; his mother traveled incessantly to find work, he lived in and out of poverty often with his grandmother as he moved from Missouri to Kansas, from Kansas to Illinois, from Illinois to Ohio, all before graduating high school. But it was his time in Cleveland, while attending Central High School between 1916 and 1920, when his passion for poetry developed most rapidly and thoroughly. Ethel Weimer’s second-year English course taught him the works of Amy Lowell, Edgar Lee Masters, Vachel Lindsay, and, most impactfully to the young Mr. Hughes, Carl Sandburg. “Although I had read of Carl Sandburg before . . . I didn’t really know him until Miss Weimer. . . . Then I began to try to write like Carl Sandburg” (Hughes 1993). The young poet was also fervently engaged in extracurricular activities and often wore a sweater that proved this; it was covered in club pins. He was on the track team, served as a lieutenant in the school’s military training corps, edited the yearbook, served as class president, occasionally made the monthly honor roll, and wrote many of his early poems for the school’s magazine, the Belfry Owl.

Moving between overpriced kitchenette apartments, Hughes witnessed the harsh realities of the segregated geography and racist economy. But he also encountered the fleeting cultural beauty that blossomed. Cleveland’s Central High School, a Victorian Gothic building on Central Avenue (since destroyed), hosted a diverse community of European immigrants from Poland, Russia, Italy, and also served a growing Black community. This made for a hotbed of radical ideas. His classmates lent him The Gadfly, introduced him to the Liberator, and took him to hear Eugene Debs speak. They knew that it was wrong that Debs was locked up, they knew that Lenin sent a shockwave from Russia to the slums of Woodlawn Avenue, “and when the Russian Revolution broke out, our school almost held a celebration” (Hughes 2002, 49).

Moving between overpriced kitchenette apartments, Hughes witnessed the harsh realities of the segregated geography and racist economy. But he also encountered the fleeting cultural beauty that blossomed. Cleveland’s Central High School, a Victorian Gothic building on Central Avenue (since destroyed), hosted a diverse community of European immigrants from Poland, Russia, Italy, and also served a growing Black community. This made for a hotbed of radical ideas. His classmates lent him The Gadfly, introduced him to the Liberator, and took him to hear Eugene Debs speak. They knew that it was wrong that Debs was locked up, they knew that Lenin sent a shockwave from Russia to the slums of Woodlawn Avenue, “and when the Russian Revolution broke out, our school almost held a celebration” (Hughes 2002, 49).

The years after graduation, like much of his life, involved a seamless continuation of movement, never finding a firm residence for more than a year, floating from one place or job to the next, but always with his sights set on his true passion: writing. From 1925 to 1930 his career picked up: he won poetry contests; published his first two books, The Weary Blues and Fine Clothes to the Jew; graduated from Lincoln University; was taken up by a wealthy patron of the arts, Mrs. Mason; and published his first novel, Not without Laughter. During the economically depressed year of 1931, Hughes traveled to Cuba and Haiti and began writing for the radical press.

“I went to Haiti to get away from my troubles,” he wrote honestly about his trip. He’d just spent Christmas with his mother in Cleveland and intended to take a bus to Key West. Fortunately for Hughes he met a fellow poet named Zell Ingram, a disenchanted student at the Cleveland School of Art who, conveniently for Hughes, was desperate to quit his classes and travel. They took Ingram’s mother’s car, both with $300 in their pocket, down to the coast. After the turbulent break with his patron, Mrs. Mason, he thought it necessary to “sit in the sun awhile and think. . . . So in Haiti I began to puzzle out how I, a Negro, could make a living in America from writing” (Hughes 1993).

In the sun, he began writing for the communist magazine New Masses, a bastion for what lead editor Mike Gold called “proletarian literature.” In its pages, Hughes warned poetically of an insurmountable foe in Havana, “a pirate called THE NATIONAL CITY BANK.” He wrote of Haiti as “a world of black people without shoes — who catch hell,” a country with a deteriorating Citadel, rusting “while the planes of the United States Marines hum daily overhead.” By the middle of their trip, Hughes and Ingram grew tired. “At this point Zell, who had never traveled before outside the confines of the U.S.A., said he wished he had stayed home in Cleveland.”

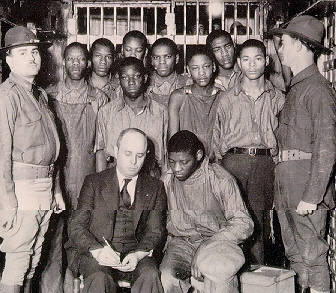

Hughes returned wearily to New York where he had little time to decompress before going on a tour of the South. In 1931 there’d been twelve known lynchings in the South, of which Hughes was painfully aware during his voyage. He wrote two poems about one of the most pressing conflicts of 1931, the Scottsboro case. “BLACK BOYS IN A SOUTHERN JAIL. / WORLD, TURN PALE!” Hughes wrote. Nine young Black men were accused of raping two white women on a freight train traveling through Alabama, and their arrest almost led to a lynching. The prosecution played out through years of court cases and appeals led by the Communist Party and the NAACP, which eventually resulted in most of the nine defendants being released. The next year he wrote a short play and four poems on the case called Scottsboro, Limited.

Hughes returned wearily to New York where he had little time to decompress before going on a tour of the South. In 1931 there’d been twelve known lynchings in the South, of which Hughes was painfully aware during his voyage. He wrote two poems about one of the most pressing conflicts of 1931, the Scottsboro case. “BLACK BOYS IN A SOUTHERN JAIL. / WORLD, TURN PALE!” Hughes wrote. Nine young Black men were accused of raping two white women on a freight train traveling through Alabama, and their arrest almost led to a lynching. The prosecution played out through years of court cases and appeals led by the Communist Party and the NAACP, which eventually resulted in most of the nine defendants being released. The next year he wrote a short play and four poems on the case called Scottsboro, Limited.

In keeping with his momentum of ceaseless travel, in the summer of 1932 the inquisitive Hughes sailed to “the land of John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World, the land where race prejudice was reported taboo, the land of the Soviets.” He was accompanied by twenty-two young Black Americans to make a Soviet-led film on race relations in the U.S. A third of his autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander ([1956] 1993), focuses on his impactful time spent in the socialist country. However, the reflections stay relatively indifferent, devoid of any strong opinions due to America’s censorship and blacklists of the 1950s.

Noticeably absent from his autobiography, for example, are his poems that speak highly of Lenin and revolution. Some of his most politically charged works have been censored from collections of his poetry; works like “One More ‘S’ in the U.S.A. [to make it Soviet]” and “Ballads of Lenin” might be conveniently omitted from an innocent collection of his wide assemblage of poems.

But he nonetheless spoke honestly of the hospitable treatment of himself and his crewmates in the USSR, who were always introduced as “representatives of the great Negro people.” “On the streets queuing up for newspapers, for cigarettes, or soft drinks, often folks in the line would say, “Let the Negro comrade go forward.” If you demurred, they would insist, ‘Please! Visitor to the front.’” Even as the movie fell apart, he noted that he’d never been paid such a high rate or lived in such comfort: “All of us were being paid regularly, wined and dined overmuch. . . . I had never stayed in such hotels in my own country since, as a rule, Negroes were not then permitted to do so. Besides, I had never had enough money for such fine living in America” (Hughes 1993).

His adventures eventually landed him humbly back in Ohio, residing with his distant cousins in Oberlin to care for his sick mother. He’d never been to the small town located not far west of Cleveland. He knew few things about the town other than that his distant cousins lived there, and that his grandmother, Mary Patterson Langston — who was married to Sheridan Leary who died fighting with John Brown — was the first Black woman to attend Oberlin College.

On his return to Ohio, Hughes engaged with the local theater scene. In the Fairfax neighborhood of Cleveland’s east side is the still standing Karamu House, the oldest African American theater in the United States, opened in 1915. Most of Hughes’ plays were developed and performed at the theater, which premiered many of his works throughout the 1930s. In 1936 and 1937 alone, Karamu House put on a stream of plays almost as quickly as Hughes could write them. This included his farce, Little Ham, a comedy titled Joy to My Soul, and a historical drama about Haiti called Troubled Island.

Perhaps itching to travel again, Hughes ventured in summer 1937 back to Europe, first to Paris for the International Writers’ Congress — where he enjoyed a venturesome excursion that included a memorable gala and the attendance of a motorcycle race with the famous photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom he’d briefly lived with in Mexico — then to Spain where he finished the year reporting on the brutal civil war for the Baltimore Afro-American. “Some of the men in the International Brigades had told me they came to Spain to help keep war and fascism from spreading. ‘War and fascism’—a great many people at home in America seemed to think those words were just a left-wing slogan.” But of course it wasn’t just a slogan to Hughes or those who fought unremittingly against fascism in Spain. Endless years of moving and traveling, Hughes wondered what the future held for him, Europe, and the world:

Would the world really end?

“Not my world,” I said to myself. “My world will not end.”

But worlds—entire nations and civilizations—do end. In the snowy night in the shadows of the old houses of Montmartre, I repeated to myself, “My world won’t end.”

But how could I be so sure? I don’t know.

For a moment I wondered. (Hughes 1993)

In the paranoia and anti-communism of the 1950s, Hughes was interrogated in March 1953 by Roy Cohn at an executive session of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He refused to “name names,” but, under the threat of being blacklisted and seeing his career ruined, renounced his radical views — but not before educating the committee members on what it meant to be an African American in America. The results of which led to a decade of relative political neutrality in his work, earning him criticisms from all sides, but keeping his career and passport intact — something many other communists had been deprived of.

Nonetheless, Langston Hughes lived a zealous life as a traveler and a poet, an activist and an artist. His communist politics developed from his early years in Cleveland to the USSR to Spain and everywhere in between. His work was torn violently by the hostilities of historical revisionism during the Cold War, the ruptures visible and unsustainable. One side of him was canonized, the other suppressed by anti-communism and cynicism. His work was effectively censored, stripped of its revolutionary foundations, and muffled of its political radicalism. But the two can be rejoined. Like the moments separating a brief strike of lightning and its booming roll of thunder, we wait patiently to hear its roll and remember that the two are intertwined. His revolutionary works sit waiting to be compounded, to strike with a lively force a new generation of “proletarian artists” who can revive the totality of Langston Hughes and bring about the “O mighty roll of the Revolution.”

Sources

Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander, Hill and Wang, (1956) 1993. epub.

Langston Hughes, The Big Sea, vol. 13 of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes. Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 2002.

Images: Top, photo by Gordon Parks, Wikipedia (Public Domain); Hughes in 1928, Wikipedia (public domain); Scottsboro defendants, Wikipedia (fair use); Republican forces in Spanish Civil War, Wikipedia (CCO).

- Tags:

- Langston Hughes

Join Now

Join Now