The following article has been adapted from a talk presented at the Little Red Schoolhouse in New York City, July 28, 2022. Part 1 was published here.

Like other forms of oppression under capitalism, the oppression of gay people gave rise to resistance and struggle. Now let’s quickly survey a few of the landmarks in Queer political history. And then we’ll take note of where the left wing and fighters for Queer freedom have overlapped far more than is recognized — including in the Communist movement. Like everything else, this too is an ongoing struggle, with its advances — and its setbacks.

1867 (about two weeks before Marx’s Das Kapital is published). Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German judge, becomes the first known person to publicly speak out in defense of homosexuality when he puts forward a resolution at a Congress of German Jurists urging the government to repeal anti-homosexual laws. He is said to be the first gay person to publicly out himself.

1897. German scientist Magnus Hirschfeld and some of his comrades in the Social Democratic Party of Germany found the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in Berlin, the world’s very first organization that advocated for both homosexual and what would become known as transgender rights. The committee’s first act was to push for repeal of Paragraph 175, which criminalized homosexuality.

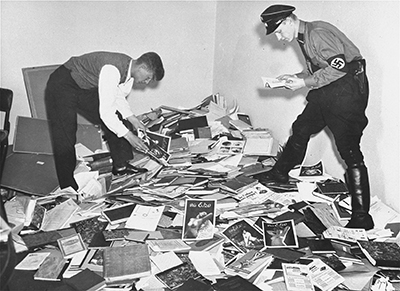

Hirschfeld would later go on to found the World League for Sexual Reform. Targeted by the Nazis for being a Jew, a socialist, and a sex researcher, Hirschfeld had to go into exile in France in 1933, where he died in 1935. The extensive archives and library of his Institute for Sexology in Berlin were burned by the Nazis, a loss still felt. This is reputed to be the first of the Nazis’ famous public book burnings, a model for all the later ones not only in fascist Germany but anywhere a regime wants to suppress knowledge. We’ve seen that in the U.S., and we’re seeing it today.

Hirschfeld would later go on to found the World League for Sexual Reform. Targeted by the Nazis for being a Jew, a socialist, and a sex researcher, Hirschfeld had to go into exile in France in 1933, where he died in 1935. The extensive archives and library of his Institute for Sexology in Berlin were burned by the Nazis, a loss still felt. This is reputed to be the first of the Nazis’ famous public book burnings, a model for all the later ones not only in fascist Germany but anywhere a regime wants to suppress knowledge. We’ve seen that in the U.S., and we’re seeing it today.

1917. Following the October Revolution, the government of Soviet Russia repeals the previous Czarist criminal code entirely, including its criminalization of homosexuality. A new criminal code passed in 1922 officially decriminalizes homosexuality. LBGTQ people start flourishing in the new USSR, though unevenly, of course: In many places it was more difficult.

1924. The Society for Human Rights, America’s first homosexual rights organization, is established in Chicago; it was disbanded within a few weeks by police.

1931. A group of Spanish transvestites, Las Carolinas, organize the first documented LGBTQ political protest in history. They demonstrated against the destruction of a public bathhouse in Barcelona that was a common meeting place at the time. One of the first targets of Franco’s fascist movement in Spain, at the outset of the Spanish Civil War, was the playwright and poet Federico García Lorca, murdered in 1936.

1933. Under Joseph Stalin, the USSR makes homosexuality a crime once more. It coincides with the implementation of a new “Family Code,” which enforces a more conventional, conservative morality around the family. Abortion is outlawed and divorce is made difficult to access — an instance of the oppression of women and the oppression of Queer people again overlapping. (Just as an aside, I visited the USSR in 1980, when these laws were still on the books and occasionally enforced. In Kiev, capital of the Ukrainian SSR, our tour guide brought us to one of the most beautiful of the historical old Orthodox churches and took us down into the catacombs where medieval monks are entombed. And she made a point of showing us a tomb occupied by two monks, saying they were extremely devoted to one another in life, and when the second one died he was laid to rest with his dear friend. This history as a subtle commentary on present-day life was not lost on any of us. And in Moscow, in front of the Bolshoi Theatre, known to be a Queer hangout, I met a gay male couple. We hit it off immediately and spent the next three days together running around Moscow with our arms around each other’s shoulders, holding hands — these were not obvious signs of homosexuality, as in America, but merely of friendship. In a way, I felt freer as a gay man in Moscow than in New York.)

Returning to our time line:

World War II. Millions of men and women were not only mobilized into the military and auxiliary forces but also recruited from small towns all over America to enter the workforce making ships, planes, and munitions and working in ports and on factory farms. In these large industrial plants and military units, larger numbers of people were gathered together than ever before in American history, and LGBTQ people found each other, far away from their hometowns. Many discovered they could construct a “gay” life for themselves and never went back.

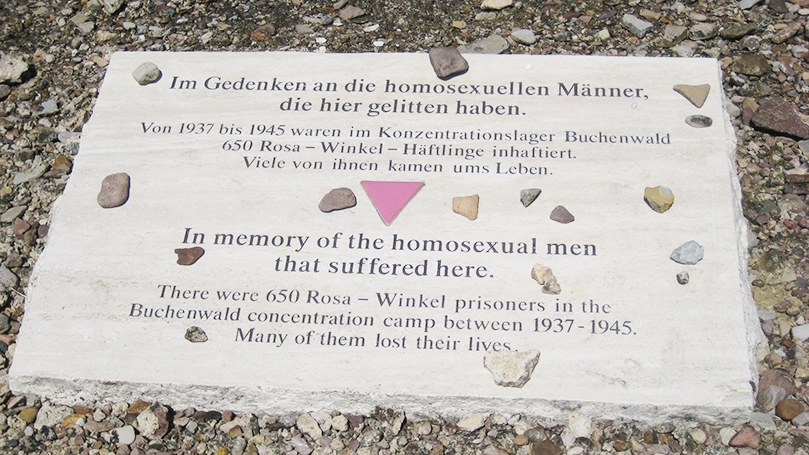

1945. The Holocaust ends with the conclusion of WW II. We don’t know how many, possibly tens of thousands of homosexuals, wearing the pink triangle, were worked to death in labor camps or murdered in the death camps alongside Jews, Roma people, Communists, Socialists, trade unionists, religious resisters, and others. Following the liberation of the camps, as many as 6,000 gay men who survived Hitler’s death machine were kept imprisoned in West Germany, required to serve out the rest of the sentences given by Nazi judges under that same old Paragraph 175 that had never been repealed.

1950. A group of former Communist Party USA members found the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles, the first sustained U.S. homosexual group. That same year, the “Lavender Scare,” alongside the anti-communist Red Scare, sees up to 5,000 individuals fired from their government jobs for being gay or lesbian — many had fought for our country in WW II. Out of that group in L.A. emerged a monthly magazine called One, which advocated for LGBTQ rights and won an important case before the Supreme Court against the Post Office, ruling that the magazine was not pornography but a serious publication addressing a legitimate social issue of concern to its readers.

1955. The Daughters of Bilitis is founded in San Francisco, the first national lesbian organization in the U.S. They publish a magazine called The Ladder.

1959. The first homosexual uprising in the U.S. happens in downtown L.A. at Cooper’s Do-nuts. A riot erupted after police attempted to arrest two drag queens, two male sex workers, and a gay man at gay bars next to the café. Donuts were flying! It was essentially a dress rehearsal for the Stonewall Rebellion that happened ten years later.

1969. The Stonewall Rebellion in New York City breaks out, a series of spontaneous demonstrations in the gay community, starting at a Mafia-owned bar in Greenwich Village in response to continuous police harassment. Among the leaders were transgender activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, a Black trans woman and a Latina trans woman. The riot is now considered the launch of the modern LGBTQ liberation struggle. The Gay Liberation Front was formed the same year, its name riffing off the National Liberation Front in Vietnam.

1969. The Stonewall Rebellion in New York City breaks out, a series of spontaneous demonstrations in the gay community, starting at a Mafia-owned bar in Greenwich Village in response to continuous police harassment. Among the leaders were transgender activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, a Black trans woman and a Latina trans woman. The riot is now considered the launch of the modern LGBTQ liberation struggle. The Gay Liberation Front was formed the same year, its name riffing off the National Liberation Front in Vietnam.

1970. The first Gay Liberation Day March is held in NYC; it was later seen as the beginning of the “Gay Pride” movement.

1973. The American Psychiatric Association removes homosexuality from its list of psychiatric disorders, prompted by a militant disruption of one of their annual conventions. Queer people are no longer “sick.”

1978. The Rainbow Flag is raised for the first time as a symbol of gay pride.

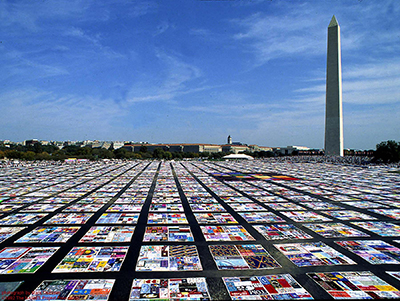

1987. The radical group AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT-UP) is founded in response to the Reagan administration’s refusal to address the HIV/AIDS crisis, which had begun in 1981.

2015. Marriage equality is the law nationwide, following a Supreme Court decision, after legalization in enough states to make it sufficiently popular and inevitable.

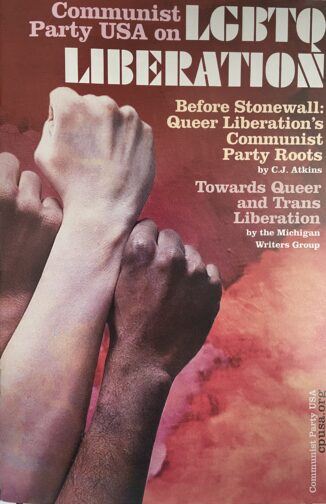

The CPUSA’s two-track history

Many LGBTQ+ Party members today, including myself, genuinely feel they can be at home not only politically but — since “the personal is political” — also personally in the CPUSA. I’ve been told that applications from prospective Party members show that up to a third or more of new Party members identify somewhere along the spectrum of Queer or non-binary sexuality. This has not always been the case, however.

Our organization has a rather tortured history when it comes to the fight for Queer liberation and LGBTQ equality. We have a kind of two-track history on this. For decades the Party held really deplorable positions on Queer equality, taking their direction —like Marx and Engels in their time — from the dominant capitalist and patriarchal culture.

Queers were met with official disdain by the CPUSA. The gay liberation movement was dismissed as bourgeois decadence, and homosexuals were included on lists of “people whom we don’t recruit,” along with drug addicts, alcoholics, racists, white supremacists, criminals, thieves, and hustlers. There were times when the fight for Queer liberation was pitted against the fight for women’s equality or against the fight for Black liberation, including by Party leaders in official meetings and publications. Gay liberation, they said, was simply not a class issue. According to this narrow formulation, and ignoring the reality that most Queer people were, after all, working-class, it elevated its own particular concern above the advancement of the working class as a whole.

Sad to say, but we must say it, the Party let first the Stonewall Rebellion, then the sexual liberation struggles of the 1970s and early 1980s, then the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic which the federal government did almost nothing to alleviate, the passage of civil rights protection laws covering LGBTQ people — the Party let all of those important fights pass it by with barely a word said in all those years. In short, the Party got it so wrong, for so long, even as almost every other left group in the U.S. took increasingly active roles in the fight for Queer liberation. Those groups could grasp the connection between the struggles, while the CPUSA could not.

Sad to say, but we must say it, the Party let first the Stonewall Rebellion, then the sexual liberation struggles of the 1970s and early 1980s, then the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic which the federal government did almost nothing to alleviate, the passage of civil rights protection laws covering LGBTQ people — the Party let all of those important fights pass it by with barely a word said in all those years. In short, the Party got it so wrong, for so long, even as almost every other left group in the U.S. took increasingly active roles in the fight for Queer liberation. Those groups could grasp the connection between the struggles, while the CPUSA could not.

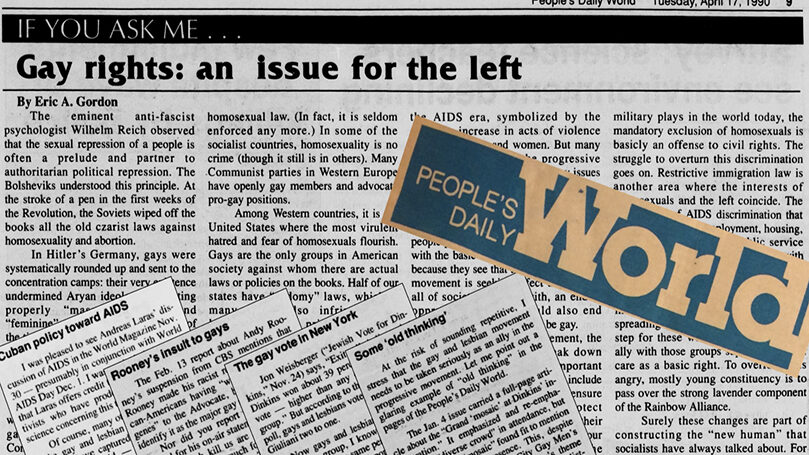

Although I embraced most of the political outlook of the CPUSA, had traveled to some of the socialist countries, and had a good gay friend in East Germany, I was not a Party member at that time. I wouldn’t have been, and they wouldn’t have accepted me. I was constantly writing letters to People’s Weekly World, only a few of them ever published, protesting their silence on life-and-death matters. Why, in New York City, with the largest concentration of CPUSA members in the country, and probably the largest gay community as well, did the Party not support measures in the New York City Council to ban anti-gay discrimination in housing and employment? That went beyond “benign neglect”; it was gratuitous insult.

In the mid-1970s, when I was living in Hartford, Connecticut, I applied to join one of the Venceremos brigades to Cuba. There was a local committee that reviewed applications, made up of several left groups, including the CP. My application was denied on the basis of being gay, a member of that committee afterward revealed to me. That wasn’t just the CP’s homophobia—some other groups’ too.

And here’s what really made my blood boil: I lived in New York from 1979 to 1990 and sang in the New York City Gay Men’s Chorus. I moved to L.A. in 1990. That year David Dinkins was the first African-American elected mayor of New York, and a huge cultural festival featuring performers and groups from the many ethnic communities of the city celebrated his inauguration. The 180-man GMC participated with a set of choral numbers, including their signature song “New York, New York.” People’s Daily World reported the festival in great, comprehensive detail — and somehow failed to mention the NYCGMC! One hundred and eighty men onstage in their matching outfits, and the reporter didn’t see them? What kind of solidarity, what kind of United Front, what kind of outreach to fellow progressive allies, what kind of democracy, what kind of decency, what kind of journalism did that represent? Their scorn for the Queer movement — Stonewall had happened over two decades before! — was simply appalling. That omission said it all: Homos are not welcome in our Rainbow Coalition! They did publish my letter on that one, I have to say. And it’s true, I was invited to write an article in 1990 about why the Party needed to finally come to grips with the Queer movement and start embracing it.

Yet it would still be another decade before that would come about.

Why were we so backward then? It was said that homosexuals were a security risk, subject to blackmail, subject to “outing” at a time when the CP already had enough problems with McCarthyism. A psychiatrist that a gay Communist might have seen could be ordered or manipulated to cooperate with the authorities and reveal Party secrets. And finally, if the beacon of socialism in the world, shining from the Kremlin in Moscow, had made its determination on homosexuality, who were we to say they were wrong? Could we take a position so polar opposite to our comrades in Europe, Asia, Cuba? Such controversy would only be divisive.

A second track

However! There is a second track of CPUSA history on this struggle, one that’s gone unnoticed by most people other than a few scholars of the Queer movement. And that is the reality, which more people need to become aware of and acknowledge, that the modern movement for Queer liberation actually wouldn’t exist without the Communist Party USA!

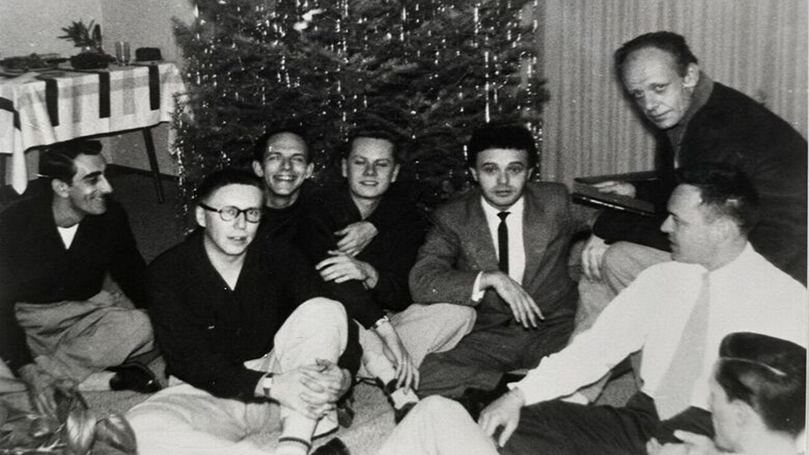

Because it was Marxist Queers—like Harry Hay, Chuck Rowland, Bob Hull, and others—who took the theory and strategy they learned as members of the Party in the 1930s and 1940s and helped found what became the movement for LGBTQ freedom. They established the Mattachine Society in 1950, the first sustained gay political organization in our country. The organization’s principles were rooted in theory that its founders had picked up in the Party. Harry, for instance, had been a full-time educator in the CP in California, but he left—or was told to leave—as McCarthyism ramped up, on the premise that homosexual political organizing would be used to damage the Party.

And that premise was true: Sen. Joe McCarthy once said that to be against him, one had to be a cocksucker or a Communist, and Harry Hay was both.

In developing a political outlook for gay liberation, Hay and Rowland drew on the Communist analysis of Black Americans as an oppressed national minority to posit a theory of homosexuals as an oppressed social and cultural minority. In L.A., they also drew on the Mexican-American experience, the demonization of Japanese-American citizens, and the genocide against Native Americans. Drawing on historical materialist methodology, Hay used whatever materials he could find to develop a Marxist analysis of gay oppression. And he certainly had to have been aware of Magnus Hirschfeld’s work in Germany from a generation or two before that had also identified Queer people as a despised and discriminated-against community. As we did earlier in this presentation, Hay focused on the oppression of women, the rise of capitalism, and changes in the family brought by industrialization as his starting points. His work was incomplete and was picked up and expanded by later radicals.

Along with a historical materialist analysis of the Gay Question, Mattachine also attempted to follow the CPUSA’s 1930s and ’40s Popular Front strategy of uniting with other oppressed groups and working together to bring about social change.

By this time they were no longer capital-C Communists, but they always said it was Marxism-Leninism that gave them the tools to theorize LGBTQ people as an oppressed minority that had a stake in fighting for the overthrow of patriarchal capitalism.

Yet ironically it was precisely their Marxism that eventually got them kicked out of Mattachine: Other members of the organization did not seek sexual liberation or the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism. Instead, they wanted to just assimilate into existing society and not be criminalized or fired from their jobs. Caving to anti-communism, they engineered the expulsion of the veteran communists who had founded the group. It was one of the earliest instances of the divide within the Queer movement between assimilation and liberation.

In the late 1980s, the Party slowly began to change. In 1986–87, a group of YCL members in New York, mostly high school students, began discussions on gay rights. When Gus Hall heard about these discussions, he encouraged the youth to pass a resolution in the YCL in support of gay rights. But it’s really only in 2001, at the Communist Party’s 27th National Convention, that these two tracks begin to merge. Thanks to the work of comrades like Gary Dotterman and others on the inside, and friendly but pointed criticism from the outside, from people such as myself, the convention passed a resolution that for the first time committed the CPUSA to be a part of the fight for LGBTQ equality. Just 21 years ago — not a very long time.

Since then it was Queer leaders in the YCL like Adam Tenney, Jesse Marshall, Erica Smiley, Flavio Casoy, and others who worked to push the whole Party forward on these matters. And since then, to its credit, the Party has never wavered from speaking up against injustices and showing up when it comes to Pride and all manner of demonstrations and organizing efforts. At the 2014 National Convention, retiring Party Chair Sam Webb summed up the developments and achievements of his tenure, and cited the firm embrace of the LGBTQ movement as one of them. Two of the most persistent critics of the Party who helped it grow were at that convention, and he asked us both to stand and be recognized — Gary Dotterman and myself. People’s World, with its small staff and network of volunteer contributors, strives to give all attention possible to current LGBTQ stories, including trans struggles, though the site always depends on contributions from more on-the-ground activist-journalists.

As for leadership, there are today a number of out Queer leaders on the National Committee and National Board of the party and on the editorial board of People’s World — though, again, more are needed, as could be said about a number of other minority representations as well. Our public Queer faces are still not as diverse as they should be. The emergence of more young Queer leaders in local clubs around the country, and the diversity of sexual orientation and gender identity among the young comrades who are attending this National Party School are encouraging signs that the generations coming up are going to help change the face of the Party even more.

As for leadership, there are today a number of out Queer leaders on the National Committee and National Board of the party and on the editorial board of People’s World — though, again, more are needed, as could be said about a number of other minority representations as well. Our public Queer faces are still not as diverse as they should be. The emergence of more young Queer leaders in local clubs around the country, and the diversity of sexual orientation and gender identity among the young comrades who are attending this National Party School are encouraging signs that the generations coming up are going to help change the face of the Party even more.

As you go out and about in your political lives, sooner or later some of you will be asked, “How can you be a member of the CP? They’re so homophobic!” Unfortunately, the odor of that long history still lingers around the Party, I regret to say. But you can honestly answer, “Yes, I know all about that, and it was awful at that time. But things are very different now. Lessons have been learned. At the same time there is also a positive side to our history too in that Harry Hay and others came right out of our Party, which you may not have known. Check out our Party website and read People’s World, you’ll see for yourself.”

Building something new

Marxism holds that people make their own history, even if they can’t always choose the timing or the nature of their battles. They have to work with what they’re given, what they’ve inherited. But if the oppressive structures that we face were constructed by humans, then we can also tear them down and build something new in their place.

With recent Supreme Court decisions, and others clearly coming down from this Trump-dominated Court, progressive Americans, including the CPUSA, are forced to devote a tremendous amount of time and treasure to defending and restoring what we had already achieved. Ideally, this struggle will bring us into close partnership with many other allies from whom we will learn and grow, and who will also learn and grow from us. We will be there!

In many ways these will be defensive fights. But these new movements will prepare us, steel us, for the longer struggle to create a different kind of society, one that is based fundamentally on human need and not profit, not the privilege of the few, and that has the potential — the potential, not the guarantee — of putting an end to modern sexual and gender definitions and limitations. And that would be a victory for everyone, because it’s not just Queer people who are held back by capitalism and its restrictive social norms and roles. The free development of all people is repressed by this socioeconomic system.

As we said earlier, neither Marx nor Engels was a paragon of enlightenment when it comes to LGBTQ issues or sexual liberation. But Marxists have always believed that only a socialist revolution could open the way to sexual freedom and equality. Despite the limitations of his own 19th-century understanding of sexuality, Engels went right to the heart of the matter in The Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State. Listen to this — he’s speaking to every future generation:

What we can conjecture about the way in which sexual relations will be ordered after the impending overthrow of capitalist production is mainly of a negative character, limited for the most part to what will disappear. But what will there be new? That will be answered when a new generation has grown up. When these people are in the world they will care precious little what anybody today thinks they ought to do; they will make their own practice and their corresponding public opinion about the sexual practice of each individual—and that will be the end of it.

Earlier I spoke of my friend and mentor Betty Millard. I also knew Harry Hay. I sure wish they were still with us. I’d be the first one to try to recruit them back into the CPUSA!

Marxism, as developed by generations of activists and analysts, gives us the tools to understand where LGBTQ oppression comes from, how capitalism benefits from it, and a strategy to fight back and win. It’s up to us to take those lessons, apply them in action in the struggles and organizations we’re a part of, and keep updating them—because as the material conditions of society change, our theory has to keep up. You can be absolutely sure that whatever is in the vanguard today will tomorrow be old news.

Images: Pride March 2021, New York City, CPUSA; Magnus Hirschfeld’s library plundered by Nazis, Wikipedia (public domain); Memorial to gay men killed at Buchenwald, Gorodilova, Wikipedia (public domain); Stonewall Inn, Rhododentrites, Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0); AIDS memorial quilt, National Institutes of Health, Wikipedia (public domain); People’s Daily World articles by author, Peoples’ World; Mattachine Society founders (Harry Hay, top right), Jim Gruber, Wikipedia (public domain).

Join Now

Join Now