Why are workers endlessly fighting poverty wages, a mass incarceration system that can’t stop imprisoning and even killing our people, and interminable roadblocks to a fully funded and equitable public education system? Why does this country seem unable to stop forcing millions of its people to live in fear of deportation? Why do we, like a pendulum, move between one political party that preys on our worst views and ideas, while the other seems unable or unwilling to making permanent change?

Questions like these have few satisfactory answers and raise serious doubts about the functioning of the U.S. political-economic system. While the legitimacy of capitalism itself — an undeniably racist, corrupt, and violent project — is put into doubt by this reality, few people attempt to think beyond it. Two recent books, in which so many of the right questions have been asked, reveal this limit: Jim Freeman’s Rich Thanks to Racism and Heather McGhee’s The Sum of Us. While both explore the dangerous strife manufactured strategically by capitalists, neither author regards racism as a necessary feature of the capitalist system itself, leaving in doubt whether their approaches to the problem offer the best solutions.

The obligatory fight against racism, for full equality of Black, Brown, Indigenous, and people of color today is immediately decisive to relieve the widespread suffering and enhance the well-being of people targeted for extra-exploitation and oppression. It is one of the indispensable features of working-class unity and its strategic sources of strength. Democratic struggles, however, are limited to temporary solutions and half measures — as meaningful as can be — unless we build a clear vision for transforming the social relations and the balance of power between owners of capital and the working-class majority.

1% racism

Freeman, a civil rights lawyer, criticizes mainstream approaches that erroneously define these questions as policy failures. Problems of inequality and working-class powerlessness are caused fundamentally by what he calls “strategic racism” deployed by corporate America, Wall Street CEOs, and the ultra-wealthy class of billionaires and multimillionaires. They deploy “strategic racism” to advance profit-seeking goals. For example, corporations like CoreCivic or the GEO Group directly profit from private prisons and immigration detention centers. He lists an array of finance capital, information technology companies, weapons manufacturers, builders, security firms, and communications technology businesses. Amazon, Microsoft, Motorola, Chase, Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, IBM, Lockheed Martin, FedEx, Bank of America, Northrup Grumman, JP Morgan, McDonald’s, State Farm, Black Rock, and a host of others are on the hook.

Capitalists realize massive profits from the world’s largest, most abusive system ever of mass incarceration, criminalization, militarization, and surveillance. Not only is it unable to keep us “safe” from crime, but this system deliberately targets and occupies many people of color communities and many of the countries of the world.

McGhee, an attorney with decades of experience in social justice think tanks, also identifies the universal harms of 1% racism. While both authors acknowledge the complicity of most whites in the reproduction of white supremacy, they generally agree that racism harms the bulk of the 99%, even most white workers and small business owners. This deep, long-term harm, they argue, outweighs almost all immediate benefits provided by white privilege.

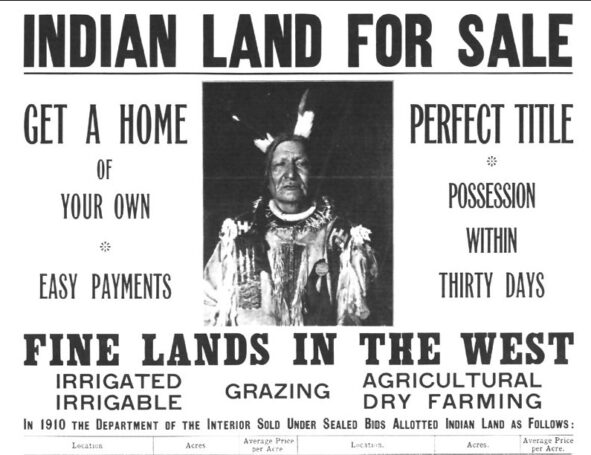

For example, McGhee writes, “The advantages that white people [have] accumulated were free and usually invisible, and so conferred an elevated status that seemed natural and almost innate.” The white accumulation of power and wealth transcends history: access to the right to vote, the nearly exclusive acquisition of stolen Native lands through the Homestead Act which created 1.6 million white landowners (who today have more than 45 million descendants), the denial of wage and union protections to occupations worked predominantly by Black men and women in domestic service and agricultural labor, the systemic distribution of federally insured and subsidized home loans to white households combined with their overt denial to Black and Brown families. These policies created a substantial middle-income grouping of white people with big aspirations for more who became convinced they deserved these material benefits because of their race, and conversely that Black and Brown people did not merit them.

For example, McGhee writes, “The advantages that white people [have] accumulated were free and usually invisible, and so conferred an elevated status that seemed natural and almost innate.” The white accumulation of power and wealth transcends history: access to the right to vote, the nearly exclusive acquisition of stolen Native lands through the Homestead Act which created 1.6 million white landowners (who today have more than 45 million descendants), the denial of wage and union protections to occupations worked predominantly by Black men and women in domestic service and agricultural labor, the systemic distribution of federally insured and subsidized home loans to white households combined with their overt denial to Black and Brown families. These policies created a substantial middle-income grouping of white people with big aspirations for more who became convinced they deserved these material benefits because of their race, and conversely that Black and Brown people did not merit them.

Nissan workers in Canton, Mississippi provide an appropriate example. In 2017 the workers lost a union-organizing vote. Divisions along lines of “race” and income lay at the heart of that process, according to McGhee. Upon its arrival in Mississippi, the company hired a mostly white workforce, offering wages comparable to unionized workers in Detroit. Over the years, however, it created a divided workforce through tiers of “temporary” workers to supplement a shrinking number of permanent workers. The “temps,” as it turns out, worked full-time but waited for years to be classified as such. This meant they were unable to participate in the union election in 2017. It also turns out that the “temps” were majority Black.

By tactically forging this linked set of race and wage differences, Nissan executives manipulated racist attitudes. They connected higher-paid, white “legacy” workers’ “hard work” with the company’s brand, while lower-paid, mostly Black “temps” who wanted a union were characterized as lazy complainers. When the organizing drive began led by the “temps,” “legacy” workers deployed this rhetoric on cue.But everyone knew that many “legacy” jobs were “cush” jobs, while “temps” did most of the menial and difficult jobs. “Legacy” workers ironically “coasted” on wage standards set by the historical battles of the multiracial, unionized autoworkers in Detroit, even as they claimed Black people wanted a union because they are lazy.

Many material benefits that accrue to white people can be sourced to successful working-class struggles that almost always depended on anti-racist organizing drives, McGhee argues. To achieve even the wage levels Nissan’s “legacy” workers enjoyed, the UAW rank-and-file fought to overcome racism among themselves and in their communities, and the racist dividing tactics of their manipulative bosses. Those battles depended on building successful relationships among workers across racial divides, throughout entire communities. There is no doubt that when Nissan decides it can more profitably produce cars elsewhere, they will leave behind even the white “legacy” workers without remorse.

Despite this reality of white complicity, McGhee adds, racism “has always optimally benefitted only the few while limiting the potential of the rest of us, and therefore the whole.” Only the “worst elements” of society benefited the most from the “immiseration” of people of color, from the founding of the U.S. to the present. “Competition across demographic groups was the defining characteristic of the American labor market,” she writes, “but the stratification only helped the employer.”

Subtle distinctions

Freeman produces some ideological problems when he talks about how racial capitalism pushes “our people to be effectively shut out of our democracy.” He also sometimes frames systems and classes in non-systemic ways: “our country doesn’t love us back,” or “currently,” the rules of the political system favor the wealthy. Such frames suggest that class- and racism-based power differences are not intended as permanent features of the constitutional order. The appeal to a supposed common national identity and morality — “our [national] system of values” — contradicts concepts of distinct materially and ideologically based classes (the capitalist class and the working class) and semi-autonomous groups constructed as “races,” which occasionally informs his thinking.

For example, his appeal to “us” — U.S. people — to live up to “our” values by more fairly distributing power contradicts his call to move beyond “provincial politics” to “build a just, equitable, and truly democratic society.” I do not think he sees this contradiction. Rather, he seems to regard his claims as simple extensions of one another. If enough whites joined in anti-racist struggles with people of color and (a multiclass, multiracial) “we” shifted the dominant political narrative to limit the influence of powerful corporations, then existing institutions may function more properly to establish more socially just outcomes.

Freeman illustrates his model of destructive racist competition with a parable about Team A and Team B pitted in “a grueling and perilous race.” While Team A is given a decisive head start for the competition, its members ignore this fact and instead focus on their greatness. And they deploy an anti-Team B hostility rooted in inventing false explanations for why Team B seems to lose — they are biologically, culturally inferior or lazy, etc. Meanwhile, the race’s organizers steal the vast majority of the prize money unnoticed. And the competing teams rarely seem to wonder why the competition happens in the first place.

This simplistic, if illuminating parable points to, but stops short of, indexing the relation of racism to exploitative class processes in racial capitalism. Yes, capitalists steal all the money, but a critique of political economy highlights not only the fact of this theft but also its necessity, its original structure. Freeman doesn’t help his reader get to this point.

Further, Freeman’s construction of this competition creates a simplistically rendered social calculus. History reveals to us that most people in Team A aren’t ignorant of the advantage they have been given, but believe it is their natural right as “real Americans” or “real Christians” or as “civilized,” etc. Instead, they get mad when they are reminded of that. They deny it, raise charges of reverse discrimination, and even try to find ways to silence those who point it out.

McGhee is more aware of the contradiction. The “us” in her title is less an objective reality and more of a hoped-for collectivity. She recognizes that many whites are fully cognizant and even supportive of racism. She identifies research that shows only about 20% of whites are consistently and actively sympathetic to Black and Brown people’s experiences with racism. Still, her project is to provide hard data that can “destroy the idea” at the heart of racism that “the well-being of people of color is a threat to white status.” She aims to expose how white racism destroys white working-class security, threatens the cultural and educational development of white workers, and positions them as perpetually subjugated to the power and agenda of the 1%.

McGhee’s swimming pool example effectively illustrates the triangulation of social forces in her model of U.S. racism that is distinct from Freeman’s. First, she argues that the level of social, cultural, technological, and infrastructural development of a given (capitalist) society reflects the particular needs and interests of the ruling 1%. The southern slaveocracy, for example, refused to build public schools or other public resources because its economic development depended on uneducated, enslaved people and a global market, not on a developed working class that imagined itself as a middle-class of consumers.

Second, with this premise in mind, she tells the story of the desegregation struggles of public swimming pools in places like Warren, Ohio, and Winona, Mississippi. For most whites, public swimming pools meant the white public, and Black people were denied access. When the Supreme Court ordered desegregation of such facilities, local white leaders closed the pools rather than share them. The point is that whites (across social classes) seemed to prefer to go without rather than share public resources of which they claimed ownership by virtue of race. This data reveals how white privilege as a set of material benefits are readily exchanged in the name of anti-Black hatred.

The 1% agenda

According to Freeman, the capitalist class (the 1%) has effectively organized multiple interlinked political organizations (such as the American Legislative Exchange Council) to mobilize the state to protect the narrow class interests, resolve intra-class competition, create class-based strategy and tactics that manipulate democratic procedures, frame their agenda in the media, and test new ideas. They do so through funding and organizing legislators on multiple levels of government to advance their agenda across multiple jurisdictions.

The 1%’s agenda involves gutting and privatizing public services such as social welfare and public education, ensuring that healthcare attends to the profits mainly of powerful insurance companies (finance capital). While hundreds of billions of dollars are funneled through contracts to already wealthy and powerful corporations, we are often falsely convinced that we have no resources for public services or social programs. Indeed, we are often convinced that social benefits can be delivered only on a competitive basis, where “one community’s gain is another’s loss” — leading the racial majority to claim the most of the shrinking pie.

Freeman traces the powerful capitalist-controlled organizations behind these trends to the same sources as groups who attack civil rights and immigrants and promote white anxiety and hostility toward racial minorities. He shows how they deploy a politics of resentment, especially white resentment about everything from affirmative action to school desegregation to “they’re stealing our jobs,” to further their anti-working-class agenda. For example, racist targeting of immigrants in Arizona drew on coordinated right-wing resources to build a massive, long-term culture of hostility toward Latinx migrants. The same politicians who push this agenda vote to weaken labor unions, reduce taxes for the rich, bloat military spending, resist efforts to raise the minimum wage, and stall or block real environmental protections that may save humanity from its self-driven destruction.

The 1% agenda and the harm deployed by the zero-sum racial competition fallacy are revealed in McGhee’s discussion of the struggle in Maine to expand Medicaid under Obamacare. In this ideological framework, whites (of all classes) believe that any benefit that goes to people of color comes at a cost to them. This way of thinking helped Maine’s former governor, Paul LePage, a Trump loyalist, win support to block Medicaid expansion because African and Latinx immigrants would use it. Many whites, who would have qualified for expanded Medicaid benefits, refused initially to support the expansion for this self-destructive reason. Fortunately, a statewide ballot initiative finally defeated LePage’s racist hostility.

How to change it

Freeman argues, correctly, that if just a few white people in every local community got involved with anti-racist organizations, they could help deepen their impact. People of color are consistently fighting and organizing against racist social policies. And they occasionally win. But broader success could occur with inter-racial interactions and activism. He argues that whites have special insights and valuable experiences with racism that may be useful to winning social change. Aware of the problem of white savior-ism, or the idea that real change can happen only if white people swoop in to save the day, Freeman remains convinced that white people must fight for change, but must not dominate the process (good for him!). He devotes an entire chapter to identifying community organizations and coalitions who are strategically positioned in the anti-racist fight.

His research and reporting explore the powerful class and racist forces that preserve white supremacy as an essential feature of capitalism. In so doing, capitalism requires an army of (usually unwitting) “foot soldiers” from among the so-called middle classes and the working class who support racist policies. White political engagement may become a learning mechanism that can reverse this trend. Freeman argues that peeling whites away from the racist veneer of the 1% agenda can mobilize, slowly but surely, new momentum. And, when they become aware of the cost to them of that 1% agenda, their interests and motives will shift.

McGhee shares the perspective but emphasizes that the erosion of structured advantages for whites due to deindustrialization, globalization, and the elimination of public services enable whites to see the world more clearly. Her optimism about the possibility for a sea change in racism stems from radical structural changes in U.S. capitalism. These changes, even as they are boosting corporate profits and the fortunes of billionaires, are driving down wages for many segments of the working class, placing more and more workers into closer social proximity. Social proximity makes the cynicism of 1% racism easier for more white workers to see through. Painful events such as the opioid crisis, the pandemic, and social isolation that harm many communities in the neoliberal era open eyes. The response of the dominant class to the opium crisis as a public health crisis rather than a criminal problem (which continues to function as the main response to social crisis in Black and Brown communities) reveals the pervasive power and appeal of white racism.

Rather than a motive for more racial hate, economic anxiety caused by wage compression may be a powerful force for successful anti-racist organizing, McGhee argues. Still, other forms of separation—housing and school segregation, job discrimination, distorted cultural stereotypes, and religious differences—also create divisions that add to the social distance between communities of color and Euro-Americans. Anti-racist struggles must account for these additional sources of harm and cannot simply focus on wage and wealth gaps, as decisive as those are. Reestablishing and strengthening new forms of a multi-racial working-class community — the further deliberate reduction of spatial and social distance — often helps whites who have been discarded or abused by capitalism to restore a sense of shared place and identity and build new political power.

Limits

Failing to talk about stratifications in capitalism as systemic necessities reveals the limits to liberation posed by these two books. As capitalism lurches from crisis to crisis, worsening as it goes, it needs, seeks, and creates new ways to stanch the loss of life-giving capital accumulation. Wars, disease, starvation, destruction, coups, abuse, and addiction are the symptoms. Failure to articulate this truth blocks from view a broader horizon of human liberation. Capitalism cannot develop, accumulate, and overcome crisis after crisis without super-exploitation, the critical function (from the capitalists’ point of view) of racism. Imperialism, the highest and latest stage, cannot operate without the international dimension of this competition. Simply put, it needs to systemize the perpetual abuse of millions of people (war, torture, imprisonment, racism, disease, hatred) to function as intended.

A broader political horizon should lead the working-class to better policy choices in the immediate struggles. Democratic rights and the increased power of the working class — for example, voting protections, divestment of policing in favor of community control of public safety, the PRO Act, the minimum wage raise, student debt cancellation — should be prioritized equally or above things like infrastructure investments.

The latter will rebuild the public swimming pool but does nothing to stop white people from believing they own it. It may even encourage such delusions.

Images: Confederate-flag wavers, John Ramspott (CC BY 2.0); “Indian Land for Sale” sign, Library of Congress, no known restrictions; Segregated swimming pool in North Carolina closed down after four Black males went swimming, David Hoffman (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Save Medicaid, Adam Fagen (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Covid isolation, Mattia Ferrari (CC BY-NC-SA).

Join Now

Join Now