“Peaceful coexistence” between nations sounds like a pipe dream today. But as a concept and policy, peaceful coexistence of countries with different social systems was birthed during the Cold War, when tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union were at their highest, and nuclear war was such a real possibility that school children were trained to “duck and cover” during air raid drills.

What is the history of peaceful coexistence? What can we learn from it to understand the struggle for peace today?

“Peaceful coexistence” as a concept was used first by the Soviet Union during the high Cold War period of the 1950s. It was during this period that the CPSU and the world communist movement advanced the concepts of peaceful coexistence, peaceful competition, and peaceful transition, the latter of which imagined that socialism could be achieved without a civil war.

Peaceful coexistence was picked up by the movement of “non-aligned nations,” the African and Asian nations emerging from the old colonial empires after World War II.

These nations met at Bandung in Indonesia, itself a major colony of the former Dutch empire in 1955. They called for a policy of peace and cooperation outside the military alliances that the United States and the Soviet Union had created in Europe and that the U.S. was creating in Asia and the Near East. The People’s Republic of China attended the conference six years after its establishment as a nation committed to the construction of socialism and opposed to imperialism.

From this conference the idea of a “third world,” representing most of the people of the world (the peoples of Africa, the Asia Pacific, and Latin America), came into existence. Many of these new nations had been strongly influenced by socialism in their struggle to free themselves, and some sought a socialist path for development.

However, what did “peaceful coexistence” as a policy mean? It should be recalled that the U.S. bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki near the end of World War II. Many, including the leadership of the USSR, interpreted this as a political as well as military warning aimed at the Red Army.

This was accompanied by Winston Churchill’s infamous “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton Missouri in 1946. Small wonder that the U.S. and its NAT0 allies rejected the idea from its inception as “Communist propaganda.” The aim of U.S. global policy, as stated in the 1947 Truman Doctrine, was to “contain” revolutionary movements by defining them as a Soviet and later “Sino Soviet” conspiracy for “Communist world domination.” The first application of this doctrine occurred the same year, when Congress passed the Greek-Turkish Aid Act, which provided military aid to Greece during the civil war against Communist-led revolutionary forces.

This was accompanied by Winston Churchill’s infamous “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton Missouri in 1946. Small wonder that the U.S. and its NAT0 allies rejected the idea from its inception as “Communist propaganda.” The aim of U.S. global policy, as stated in the 1947 Truman Doctrine, was to “contain” revolutionary movements by defining them as a Soviet and later “Sino Soviet” conspiracy for “Communist world domination.” The first application of this doctrine occurred the same year, when Congress passed the Greek-Turkish Aid Act, which provided military aid to Greece during the civil war against Communist-led revolutionary forces.

The U.S. response to the postwar world situation had been to reorganize and greatly expand its economic, military, and intelligence forces. It also began to establish regional anti-Communist military alliances, starting with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (1949) aimed at both the Soviet Union and the then large and influential communist parties of France and Italy.

Previously, the U.S. had refused to share nuclear information with the Soviet Union and had opposed a serious plan to achieve nuclear disarmament in the first years of the United Nations. After the Soviets exploded a nuclear device in 1949, conservative politicians and mass media blamed this on Soviet and Communist spies and launched a crash program to build a more devastating hydrogen bomb. The nuclear arms race that followed would grow vastly more expensive and deadly with the development of long-range bombers and multi-warhead (multi-bomb) medium- and long-range guided missiles.

By the 1960s, the U.S. idea of coexistence had taken the form of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD), that is, a “peace” policy intended to deter the Soviets or any other major power from launching a nuclear world war by expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal both quantitatively and qualitatively.

However, “mutually assured destruction” did not apply to the U.S. and its allies intervening in civil wars and other conflicts to support governments and forces it defined as part of the “free world.” In a contradiction worthy of the novel Catch-22 or the film Dr. Strangelove, these interventions were defined as alternatives preferable to a nuclear world war.

The U.S. “success” in supporting reactionary forces to defeat Communist-led insurgents in the Greek Civil War (1947–49) was not only followed by the establishment of NATO but also U.S. intervention with its NATO and Asian allies in the Korean Civil War (1950–53). The hostilities ended in a bloody stalemate where it had begun at the 38th parallel, resulting in an estimated 3 million casualties. An armistice was declared in 1953, but to this day, the war has not been declared officially over.

The Korean War was followed by the U.S. establishment of an Asia-based military alliance, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). The U.S. also replaced France in Indochina to establish an anti-Communist “protectorate” in South Vietnam in direct violation of the 1954 agreement which followed the defeat of the French colonial forces at the hands of the Vietminh led by Vietnamese Communists. Finally, the U.S. established a military treaty for the Middle East, the Baghdad Pact, which brought the Iraq and Iranian monarchies together with Turkey, a NATO state.

While these alliances became unstable, with nations falling in and out, they were the opposite of coexistence, as both socialist countries and the non-aligned nations of the third world understood it. The Marxist-oriented sociologist C. Wright Mills referred to this policy as “crackpot realism” in the 1950s, meaning that military intervention would be carried out regardless of the outcome—“victory” in Greece, stalemate in Korea, and later defeat in Vietnam.

However, did the Soviet Union and its allies pursue the policy of peaceful coexistence in a consistent way, making its achievement possible? While hindsight is 20/20, the answer is complicated and contested.

The phrase was most associated with the Soviet leader, Nikita Khruschev, who gained leadership of the CPSU and USSR by 1955. The Soviet leadership initially sought a thaw in Cold War conflicts: they issued a Soviet ban on above-ground nuclear testing and even offered to support German reunification under conditions which would have meant the end of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) for a pledge to keep a unified Germany from being remilitarized and joining NATO.

When the Eisenhower administration refused this offer, the Soviets created their own, much weaker alliance in Eastern Europe, the Warsaw Treaty Organization, to oppose NATO. There was a large strategic gap between the new alliance and the U.S.-NATO forces, which encircled the Soviet Union from West Germany to Turkey. The U.S. and NATO had bases in Europe and Turkey near the Warsaw Treaty nations and the USSR, but the Soviets had no bases near the U.S., which was a difference in quality. The Soviets were the only nuclear power in the Warsaw Treaty, while Britain and France were nuclear powers in NATO; also, the U.S. stockpiled more nuclear weapons than the USSR. The Khrushchev leadership greatly expanded the Soviet nuclear weapons program to try to make up in quantity what it could not match in quality, but at great cost.

Some consider that, while the Soviets provided developmental aid to Egypt and other countries of the non-aligned nations, its interest in its own Soviet/Warsaw Treaty bloc led it to do little to oppose U.S. militarization in Asia and direct threats against the People’s Republic of China. These policies would divide the USSR and the PRC in a disastrous way, leading to the breakup in 1949 of what had been seen as an emerging “socialist camp.”

On the other hand, national liberation movements in Southeast Asia (Vietnam and Laos) and Africa (Angola, Mozambique, South Africa) credit the USSR with providing invaluable military aid and political support. Soviet support for the Cuban revolution, in what had been a U.S. neo colony since the Spanish American war of 1898, was essential to its survival. However, the Cuban/Soviet decision to construct nuclear facilities in Cuba in 1962 led to the missile crisis, which came close to leading to a nuclear WW III and the likely death of hundreds of millions of people.

The missile deployment was essentially an attempt to do to the U.S. what the U.S had been doing to the Soviet Union many times over. In addition, the Soviet argument for their action had some merit: they were defending the Cuban revolution from likely new U.S. attacks in the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion.

However, the missile crisis led the U.S. to intensify its military interventionism and the Soviets to continue Khrushchev’s policy after his removal of building Soviet nuclear armaments and supporting national liberation movements in Africa and Asia, actions that the U.S. opposed — sometimes with disastrous results. For example, in the 1970s, the Soviets provided arms to the anti-Communist Baath regime in Iraq after Saddam Hussein double-crossed his CIA backers. In the 1980s, with the support of the Reagan administration and the use of Soviet weapons, Hussein launched a war against Iran, which cost hundreds of thousands of lives. In Egypt, the Soviets were expelled by Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, who used Soviet weapons to launch his 1973 “Yom Kippur War” against Israel and later allied himself with the U.S. These are two examples of how the Soviets’ pursuit of its state interests — what they understood as anti-imperialist objectives — backfired.

Richard Nixon built on these Soviet failings in the 1970s to both improve relations with the USSR and develop relations with the PRC in order to play them off against each other and encourage them to end their support for revolutionary and anti-imperialist movements in the world. National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called this policy “linkage.” Nixon’s Strategic Arms Limitations Treaties, which the Soviets joined in, while a step forward, were filled with loopholes that failed to address the continued and escalating nuclear arms race.

Ronald Reagan’s election to the presidency in effect ended even the paper policy of peaceful coexistence, as Reagan launched a massive increase in U.S. military spending.

Eventually, the “counter-revolution” started by the Gorbachev leadership of the CPSU and the USSR resulted in the overthrow with Soviet support of its Warsaw Treaty allies (1989), followed two years later by the dismemberment of the Soviet Union itself.

Gorbachev’s policies resembled the appeasement policies of the 1930s. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain sought to “save” the British Empire by giving Nazi Germany all the concessions it wanted in Europe; French Field Marshall Henri Petain collaborated with the Nazis and accepted the dismemberment of France. For both Chamberlain and Petain, socialist and communist parties and the Soviets were their main enemies, views they shared with Hitler. For Mikhail Gorbachev and those he brought into power, traditional Soviet Communists in their Marxism-Leninism and internationalism were his main enemies, views he shared with Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and at the end, George H. W. Bush.

Today’s cold war policies

With tragic consequences, governments in the 21st century have not learned from the failed policies of the past — with the Bush administration’s imperialist wars in Iraq and Afghanistan being prime examples. The attempt by the Trump administration to revive the worst of the cold war against Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and the People’s Republic of China, policies which Biden administration appears to be continuing albeit with less hysterical rhetoric, can only have devastating effects on both the world economy and prospects for peace.

These policies will not work in provoking the PRC. China today is the second-largest economy in the world and is poised to replace the U.S. as the largest economy. Its developing mixed economy of socialism makes it far less vulnerable to economic and political encirclement than the Soviet Union. It has also launched international developmental initiatives, the Belt and Road Initiative being the most important, that are well beyond what the USSR ever attempted.

While in recent years supporting working-class internationalism, China has not attempted to establish military alliances or to provide military aid to forces fighting against imperialism, as did the Soviet Union. While its military spending is second to the U.S. in the world, it is roughly one-fourth of U.S. military spending, with nearly four times the population of the U.S. Military spending detracts from overall economic development under both socialist and capitalist systems (although it does provide great profits for military contractors under capitalism). U.S. cold war policies will have far more destructive effects on the U.S. economy if they are not reversed.

These policies represent a far greater threat to peace to other nations. The continued blockade against Cuba and the recent failed Biden administration policy of supporting “protests” in Cuba to overthrow Cuban socialism 60 years after the Bay of Pigs is one important example. Cuba’s accomplishments in many areas, particularly in medical research and health care, should make it a hemispheric ally of the United States. Despite U.S. policies, Cuba has made major contributions to the ongoing struggle against the COVID-19 pandemic. Ending the blockade, restoring full diplomatic relations, and working with Cuba on hemispheric health care would all be necessary components for a U.S. policy of “positive peaceful coexistence.” Also, if any hemispheric nation has a claim to receive reparations from the United States for past acts, it is Cuba.

Ongoing U.S. attempts to overthrow the socialist-oriented governments of Venezuela and Nicaragua must also be abandoned. These policies put the Biden administration in the old cold war trap that previous administrations have faced. When they fail — and they will fail — the Republican Right will make political capital out of those failures.

Another definition of peaceful coexistence

In the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. introduced to the Civil Rights movement the tactics of nonviolent civil disobedience, a concept associated with Mohandas Gandhi and the Indian National Independence movement. Gandhi’s successor, Jawaharlal Nehru, who considered himself a socialist, emerged as a leader of the non-aligned movement in the 1950s and sought to maintain positive relations with both the U.S. and the USSR while avoiding the involvement in or support for U.S. military policies.

While King became the most admired and revered American in the second half of the 20th century globally, important parts of his philosophy have been largely omitted from popular thought in the U.S.

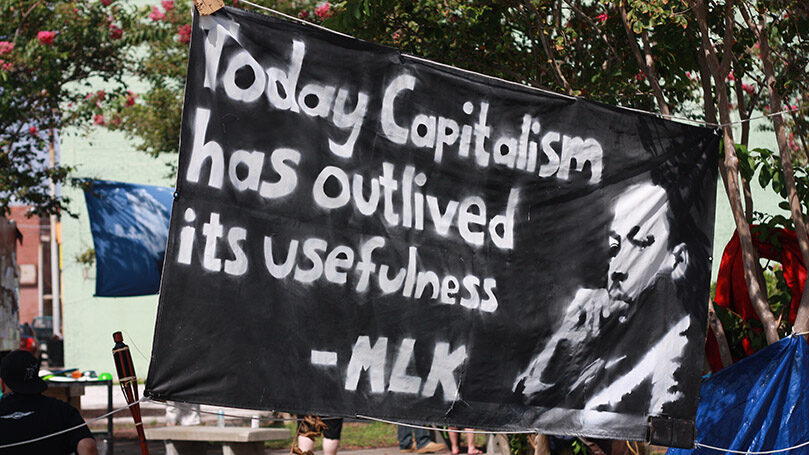

These ideas are essential to making “peaceful coexistence” into a real policy today. First, King developed the concept of “positive peace” or peace with social justice. King’s concept of social justice was rooted heavily in socialism. Instead of either seeking to suppress movements for socialism and national liberation or seeking to use them as pawns in global power politics, King called upon the U.S. to embrace these movements as essential to both the development of world peace and to the advance of social equality and justice in the U.S. and its allied countries.

King actively advanced these ideas in his militant opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and in his last struggle to mobilize a national poor people’s movement. King expressed this philosophy in this famous speech against the U.S. neo-colonial war in Vietnam in these words a year before his assassination:

These are revolutionary times. All over the globe men are revolting against old systems of exploitation and oppression, and out of the wounds of a frail world, new systems of justice and equality are being born. . . . Our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism. . . .

We still have a choice today: nonviolent coexistence or violent coannihilation. We must move past indecision to action. We must find new ways to speak for peace in Vietnam and justice throughout the developing world, a world that borders on our doors. If we do not act, we shall surely be dragged down the long, dark, and shameful corridors of time reserved for those who possess power without compassion, might without morality, and strength without sight.

King’s philosophy remains the most important guide to a genuine policy of peaceful coexistence.

What can be done to advance a policy of peaceful coexistence today?

The primary responsibility to develop such a policy rests with the United States and the American people. The U.S. still has greater military power than any nation on earth, but its economic power has stagnated and declined tremendously.

There are many reasons for this, but the decades of multi-trillion-dollar military spending over the last 70 years is the most important reason. As progressive social scientists have long noted, it took billions away from the development of education, housing, health care, transportation, and energy resources that would have raised both the living standards and the quality of life for the overwhelming majority of people in the U.S. After 1980, conservative policies of sharply reducing taxation of the wealthy and corporations, actively supporting union busting at all levels, and sharply reducing existing federal support for social welfare, led to a huge increase in both public and consumer debt and economic inequality.

To promote peaceful existence, the U.S. must end cold war–style policies such as the blockade of Cuba, support for coups against socialist-oriented governments, and the saber-rattling against the PRC. However, peaceful coexistence also calls for different policies toward governments that are neither socialist oriented nor progressive. The policy of supporting Israel, Arab states, and Turkey in dangerous maneuvering against Iran as against seeking a regional peace policy for Iran and its neighbors is an important example of this. Restoring full diplomatic recognition of Iran is a necessary beginning. Supporting a two-state solution to the Israeli/Palestine conflict would be an important first step, including ending settlements and removing the U.S. embassy from Jerusalem. Another necessity is the revival of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency, a short-lived agency that existed during 1943–47, to advance regional development and to provide support both regionally and globally to address the refugee crisis caused by wars, extreme poverty, and climate change.

These are the policies that Marxists, Communists, and all progressive people should organize for and educate their communities and countries to advance.

Images: World peace, finemayer (Pixabay); Truman applauding Churchill after the latter’s “Iron Curtain” speech, ; Scene from Dr. Strangelove, a film about mutual assured destruction, Wikipedia (public domain); Nuclear test over Bikini Atoll, Wikipedia (public domain); Hands off Cuba, Cuba Solidarity (Facebook); MLK quote, Liz Mc, Wikipedia (CC BY 2.0); Peace not war, garryknight, Openverse (public domain).

Join Now

Join Now