The History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol 11: The Great Depression 1929-1932, Philip Foner, International Publishers, New York: 2022.

A poem appeared in the underground newspaper of the Metal Workers Union, an industrial union created by Communist activists at the beginning of the Depression. It captures the initial stages of the great workers upsurge of the 1930s, which Philip Foner chronicles in the 11 volume of his History of the Labor Movement of the United States:

He’s a Democrat and a Republican

He’s a boy who runs the political crew

He runs the Socialist Party too

Money talks in this land of the free

That’s why Congress cant hear me

Who is listened to? Who is heard

The boss’s money has the last word

When there’s a strike he wants to stop

He calls in the soldier and the cop

The boss buys up political chains

To keep the workingmen in chains….

The worker must learn to break his chains

The worker must have political brains….

The boss has his parties….we have ours

So Let us join with three cheers hearty

The workers party…The Communist Party

Foner’s narrative histories and edited collections would fill an exceptionally large bookshelf. International Publishers (IP), which survived the postwar “McCarthyite” repression, published his many works in the course of a long and productive career. It is therefore fitting that IP publish this volume on the Depression, 27 years after his death.

Along with other activist scholars associated with Marxism and the CPUSA, Foner was fired from his teaching job at the City College of New York in 1941 through the activities of the Rapp-Coudert Committee of the state legislature, a local version of the House Un-American Activities Committee spearheading purges and blacklists of trade unionists, teachers, and journalists. After WWII he began to publish the first volume of his History of the Labor Movement of the United States, which focused on class organization and struggle from the American revolution on.

Foner’s work challenged what was the “official interpretation” of labor and working-class history in the U.S. associated with John R. Commons and Selig Perlman of the University of Wisconsin – that American workers actively accepted capitalism and fully supported the policies of their “business unionist” leaders, that is, they sought better wages and benefits for themselves through labor/business cooperation and nothing else. According to this view, workers were uninterested in either organizing the unorganized or larger political issues like the democratization of politics and the struggles against racism and sexism. They were, had always been, and would always be as Perlman contended, “job conscious” rather than “class conscious.”

Foner reached an international audience in challenging these views and began to influence later generations of scholars, although the attacks on him and his work never ceased in establishment circles. In 1949, he published the first volume of a five-volume history of the life and work of Frederick Douglas (International Publishers) whose own significant role in the abolitionist movement along with the movement itself had largely been buried in mainstream scholarship.

In the midst of the Civil Rights, peace, and youth movement upsurge, Foner finally received an academic position at Lincoln University, an African American College in 1967, 26 years after his firing at City College. In 1979, he and other victims of the Rapp-Coudert purge received a formal apology from the City of New York.

Foner also wrote Organized Labor and the Black Worker (1974) and a two-volume history of Women in the American Labor Movement. One could go on at great length about the breadth and depth of Foner’s work but the 11th volume of his History of Labor in the United States has special importance for the labor movement today. Foner looks at the labor movement from 1928-29, the stock market crash and the establishment of the Trade Union Unity League by communist activists and their allies to 1932-1933, the height of the Great Depression and the election of Franklin Roosevelt to the presidency.

His narrative effectively refutes the still widely circulated view that the new industrial unions established by the TUUL divided the labor movement and sought to advance strikes and unions to establish CPUSA domination over labor. On the other hand, was an example of what the CPUSA later called dual unionism. The TUUL did certainly fail in its campaign to organize new unions and one should not see it as a strategy for today . But its organizing drives and emphasis on uniting unions with communities brought young people into the labor movement who eventually would play an important role in successful organizing drives of the CIO.

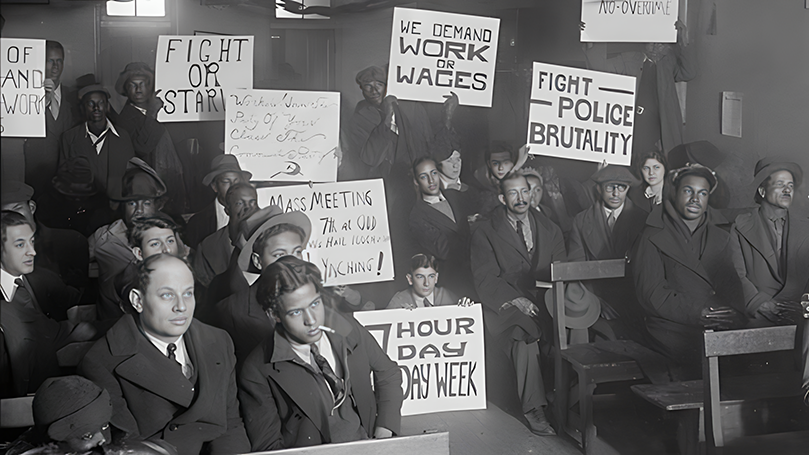

Communist activists along with their industrial unionist allies worked inside and outside the American Federation of Labor (AFL) which their political enemies and rivals refused to do. They created in 1930 “unemployed councils” to fight for “work relief” (public jobs) and “home relief”(public assistance for those who could not work, especially the disabled and women with dependent children).

They developed popular support for unemployment insurance and advanced it in their demonstrations against evictions, sit ins at local and state government buildings, and in the AFL unions where they developed significant support. At the 1932 convention of the AFL, the delegates supported unemployment insurance but the convention’s Executive Council, which had dictatorial powers, killed the proposal, denouncing it as a “Communist program.”

Foner also adds to our understanding of the often cited miner’s struggles in Harlan County, Kentucky, going well beyond the song which emerged from those struggles Which Side Are You On?1 As he surveys the work of the Trade Union Unity League’s “new unions” in mining, auto, steel, the garment industry and agriculture and the Unemployed Councils demonstrations and hunger marches, Foner includes the Black workers and women workers whom traditional historical narratives have long excluded.

In his work, Foner uses the best progressive scholarship of the 1970s and 1980s, including Roger Keeran’s the Communist Party and the Auto Workers Union and Robin Kelley’s With Hammer N Hoe, on the organization of Alabama Black sharecroppers. His rich narrative also includes poetry and songs which developed out of the struggles without which the New Deal policies which Franklin Roosevelt advanced would not have been possible, regardless of the worsening depression.

Foner also adds to our understanding of the reactionary role of the AFL leadership who used extreme anti-communism to hide the extent of their class collaboration. Matthew Woll, an AFL leader and extreme anti-Communist, had actually collaborated with businesspeople and politicians on projected national legislation to ban strikes before the stock market crash. Foner provides documentation to show that AFL unions leadership did everything they could to prevent strikes and then often worked to defeat strikes after they had formally announced their support.

There are important similarities to events today. The total labor movement represents less than ten percent of the work force as it did then, although the number of unionized workers in the public sector is significantly higher than in the private sector. The judiciary is once more in the hands of anti-labor conservatives who supported both private and public actions to block union organization. For example, the Supreme Court in the 1920s defended as enforceable the notorious “yellow dog “contract where employers demanded that employees sign an oath that they would not join any union. The courts also supported anti-strike activities by private detective agencies and local, state, and federal governments especially the use of police, state militia, national guard and as a last resort the army to break strikes.

As union organizing drives intensify and strikes develop, we can expect the conservative courts to issue injunctions to support strike breaking and criminalize tactics used by unions.

Powerful organized groups (the National Civic Federation, the NAM, later the Liberty League) fought the working class then. The Heritage Foundation, the Freedom Foundation, and the Koch brothers created ALEC now) are likely to inherit this behavior.

But there are also important positive differences. The National Labor Relations Act, even though it was to be undermined by the postwar Taft-Hartley law (giving states the right to establish anti-trade union “right to work laws” and limiting the right to strike) remains as does unemployment insurance. Staffing the NLRB with active supporters of unionization and workers rights, as it was in its early New Deal years, is now being done by the Biden Administration.

While the number of unionized workers in the private sector has dropped to pre New Deal levels, ( it’s currently 7 percent of the total work force) the leadership of the AFL-CIO supports union organizing drives and progressive political action, unlike the old AFL. And it has repudiated racist and sexist policies within its own ranks which the AFL openly advanced.

There were in the 1930s progressive factions of both parties who supported workers rights (for example, the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 which outlawed the “yellow dog” contract was advanced by two progressive Republican congress people). Today there is are no “progressive Republicans” but a large faction in the Democratic party which supports workers rights.

The threat of fascism exists today, as it did in the 1930s, especially after Hitler’s victory in Germany emboldened reactionary and fascist forces to intensify their attacks as Donald Trump’s “election” to the presidency encouraged American fascists and reactionary groups through the world.

But Trump failed to establish an open terroristic dictatorship, the political definition of a fascist state, and the January 6 2021 coup to keep him in power collapsed. Also, institutional racism, with Southern segregation as its foundation, is far less dominant in political economy and popular culture than it was then. The desperate attempt by the Republican right to re-establish it in their crusade to ban works which address racism and the history of the African American people out of all school curricula, which is both sinister and very dangerous , is also an example of its decline.

It would be foolish to suggest that Joe Biden is in any way comparable to Franklin Roosevelt, in regard to what he has represented in politics or his ability to reach masses of people and mobilize them political action

Franklin Roosevelt really connected and implemented policies with his rhetoric when the working class upsurge the TUUL, the Unemployed Councils, had helped to shape advanced qualitatively and quantitatively in the strikes of 1934, culminating in the San Francisco General Strike, led by Harry Bridges, who was closely allied with the CPUSA. Foner’s labor history unfortunately ends before that upsurge but is essential in understanding its background.

The most important lesson from Foner’s is the role of the Communist Party USA, advancing its policy of building trade unions with mass community organizations, working inside and outside the existing trade union movement and with progressive politicians at all levels. Today, among young people especially there is a re-awakening of interest in Marxism and socialism.

But as the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, a leader of the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s and a close associate of the Martin Luther King said, baseball teams don’t strike themselves out. Rattlesnakes don’t commit suicide.”

It will take determined political action of the kind that the CPUSA represented in the depression to make the “new New Deal” which many have dreamed about for the environment, education, labor and social services to finally become a reality.

[1] For Phil Foner, the culture in which the Labor movement developed as a topic of importance. Although these songs were much earlier than “Which Side Are You On?” his American Labor Songs of the Nineteenth Century (1975), received the Deems Taylor Award, presented by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP).

Join Now

Join Now