The modern movement for queer liberation—or gay liberation to use the as-yet less inclusive terminology of the 1960s and ’70s—wouldn’t exist without the Communist Party USA.

That might sound like a big claim to make, but it was Communist ideology and political strategy that provided the theoretical and practical architecture of the earliest effort to win gay equality in the United States—the Mattachine Society, a group whose ideas underpinned all the struggles and victories that have been won over the past half century.

The Stonewall Rebellion is generally (and rightly) regarded as the moment when the fight for gay rights broke out into the mainstream, led by Black and brown trans women and drag queens in New York City. Credit is certainly due for figures like Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and others who first had the courage to fight back against police repression that hot June night in 1969.

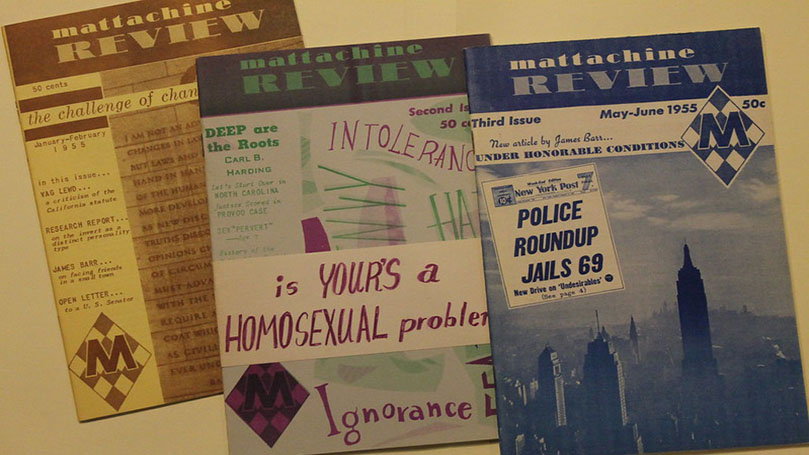

But even before Stonewall—and before the radical organizations that would follow, like the Gay Liberation Front, ACT UP, and Queer Nation—there was the Mattachine Society and Harry Hay. Mattachine, one of the first groups to attempt to politically organize gay men and lesbians, was established over the course of 1948 to 1950, a period of resurgent conservative power and suburban-inspired social conformity in U.S. culture. And Harry Hay was the Communist who combined theory and praxis to bring it into reality.

“Are you now or have you ever been a homosexual?”

Harry Hay came of age as a gay man when the notion of a gay identity barely existed; as Hay himself would often say, gay people didn’t even have a word for themselves yet. Homosexuals and “deviants” of whatever variety still understood themselves as sexually addicted, biologically defective, and mentally “handicapped.” The self-hatred and inward-focused slut-shaming ran deep.

Hay was also a Communist—at a time when first fascism and then Red Scare McCarthyism made possessing left-wing allegiances dangerous. Hay had been politicized early in life by interactions with old Wobblies from the Industrial Workers of the World, and during his work organizing migrant farm workers, but he became truly radicalized after a pair of galvanizing experiences in 1934. Witnessing police violence against mothers of starving children who were protesting the disposal of milk to protect market prices during the Great Depression, Hay instinctively picked up a brick and hurled it at a cop, striking him in the temple. He had to flee and found unexpected protection in the home of a Los Angeles drag queen named Clarabelle.

Hay was also a Communist—at a time when first fascism and then Red Scare McCarthyism made possessing left-wing allegiances dangerous. Hay had been politicized early in life by interactions with old Wobblies from the Industrial Workers of the World, and during his work organizing migrant farm workers, but he became truly radicalized after a pair of galvanizing experiences in 1934. Witnessing police violence against mothers of starving children who were protesting the disposal of milk to protect market prices during the Great Depression, Hay instinctively picked up a brick and hurled it at a cop, striking him in the temple. He had to flee and found unexpected protection in the home of a Los Angeles drag queen named Clarabelle.

Now politically active, that same summer Hay traveled to San Francisco to organize solidarity efforts for the General Strike of maritime workers that had shut down the West Coast ports. There, he saw National Guard soldiers fire on the picket lines, killing two workers on the spot, and felt bullets fly by his own head. Thousands attended the fallen workers’ funerals. Hay would later say, “You couldn’t have been a part of that and not have your life completely changed.”

For Harry Hay, that change resulted in his joining the Communist Party in 1938. He was introduced to the CPUSA by his lover, actor Will Geer (known to later generations as Grandpa on the TV series The Waltons). Over time, Hay’s involvement with the party and its various campaigns against fascism and in support of labor and what was then called Negro equality grew to become full-time devotions. He was employed for many years as an educator in the Communist Party’s political schools and community labor education associations; cultural work and the Communist-led folk music scene were other areas to which Hay devoted himself.

Never faltering in his commitment, Hay remained in the party until he felt compelled to engineer his own “honorable discharge” in 1951 so as to protect the party from any FBI security risks due to his homosexuality. By this time, he had undergone an awakening of his own sexual identity and knew there could be no going back into the closet; the “brotherhood” which he now acknowledged also demanded his loyalty. Local party leaders in California didn’t want him to go, but official CPUSA policy at the time and for decades after still saw homosexuality as a sign of the social degeneration of late-stage capitalism and as a serious blackmail risk. His request for an expulsion was eventually granted by the national leadership, but Hay was recognized as a “lifelong friend of the people.”

As it turned out, Hay was right about the potential for government manipulation; in 1955 he was summoned to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee about his Marxist proclivities. Investigators perhaps hoped that fear of being exposed as a homosexual would prompt Hay to turn on his old comrades; instead he shot back, “I’m not in the habit of confiding in stool pigeons or their buddies on this committee.”

The spark

Sen. Joe McCarthy had once joked, “If you want to be against McCarthy, you have to be either a communist or a cocksucker.” Harry Hay was both. But rather than letting his being gay and a Red become debilitating liabilities, Hay combined them and set the stage for a social and sexual revolution.

For decades, the work of Hay and the Mattachine Society remained largely unknown, a brief episode in gay history. Thanks to the work of researchers like Stuart Timmons and Will Roscoe, authors respectively of The Trouble with Harry Hay and Radically Gay, thankfully much of the story of Hay and Mattachine has been rescued from dusty boxes and locked filing cabinets. And the broad outlines of Hay’s life and the basic aspects of his work founding Mattachine have been previously presented in the pages of People’s World by historian Norman Markowitz.

The importance of the Communist Party USA to the tale was never downplayed by either Timmons or Roscoe, nor by Markowitz, but the centrality of Marxism and the CPUSA’s Popular Front strategy in this earliest effort at queer liberation has often been downplayed by other commentators who “discover” Harry Hay. His work is a part of LGBTQ history and Communist history that neither queers nor Communists have sufficiently acknowledged.

Historical materialism and the “cultural minority” thesis

The idea for a group to specifically organize gays to fight for their acceptance by society was first broached by Hay in 1948 in the form of a “Bachelors for Wallace” caucus within the Progressive Party campaign of Henry Wallace. Though it didn’t go very far, the effort eventually morphed into Bachelors Anonymous (modeled on Alcoholics Anonymous, note the addiction connotations) and then the Mattachine Society.

Hay had trouble convincing very many people in his circles that an advocacy group for people who were “that way” was even possible. Post-war reaction was setting in and progressive politics in general were under attack; what Hay was proposing was even more subversive, but he felt compelled to start organizing anyway. “I knew the government was going to look for a new enemy, a new scapegoat,” he said. Those scapegoats were Communists and queers.

Hay and the few co-organizers he gathered were trained in the party to know that, if Mattachine was going to get off the ground, they needed a theoretical foundation on which to build. Chuck Rowland, another former CP member, told author Stuart Timmons, “With my Communist background, I knew I could not work in a group without a theory. I said, ‘All right, Harry, what is our theory?’”

Hay’s years as a Marxist educator provided him the answer. “We are an oppressed minority culture,” he told Rowland. Thus was born what became known as the “Cultural Minority” thesis. Still lacking a proper vocabulary, Hay initially referred to this oppressed culture as the “Androgynous Minority.”

The notion of gays as an oppressed minority culture was a takeoff from the Marxist analysis of the oppression of African Americans and other groups as “national minorities,” a concept with a long pedigree in Marxism-Leninism but which was particularly stressed after the Sixth Congress of the Communist International in 1928. In the ultra-revolutionary days of the 1920s and ’30s, this meant U.S. Communists advocated for the “right of self-determination” for African Americans in the “Black Belt” where they constituted a majority, up to and including the right to secede from the United States and form a new nation.

The inspiration of the Cultural Minority thesis as Hay formulated it was, in retrospect, an ironic one: Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was the man largely responsible for re-criminalizing homosexuality in the USSR after the liberating early years that followed the Russian Revolution.

As a teacher in CPUSA schools, Hay had regularly used Stalin’s text Marxism and the National Question as part of his curriculum. In the book, which was counted among the Communist classics at the time, Stalin defined a “nation” as “a historically-evolved, stable community of language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a community of culture.”

Stalin’s definition wasn’t an easy fit for the situation facing African Americans—there was no distinct Black national economy, and no one yet recognized a Black linguistic vernacular—so American Communists adjusted the theorization to account for the reality that existed in their own country—African Americans had a shared territory and culture. This was how the call for a Black Belt Nation morphed into the view that African Americans were a national minority concentrated in a geographical area which possessed their own culture forged in struggle against oppression—two out of Stalin’s four criteria.

It was this aspect of the theory that Hay extended and developed as a means for understanding the oppression of homosexuals—he analyzed them as a group sharing a culture and a language (of sorts). “I felt we had two of the four . . . so clearly we were a social minority,” he later said. The publication of the famed Kinsey Report in 1948, which found that 37% of men in the U.S. had had a same-sex experience at some point in life and that 10% were exclusively homosexual, convinced Hay there were millions of people who could potentially be organized.

Chuck Rowland would say in the 1980s that by “culture,” the former Communists in Mattachine had meant a shared “body of language, feelings, thinking, and experiences.”

Being a historical materialist, though, Hay sought out evidence for the Cultural Minority thesis and found it in both the unexpected commonalities of experience that were shared by Mattachine discussion group participants and the historical examples of Native American “two spirited” persons and European “fool” traditions. It wasn’t so much individual sexual practices that he focused on in his studies, but the social institutions that had tolerated, made use of, or even fostered a distinct identity for persons that might by modern standards be seen as occupying some third space between man and woman. The Two Spirits and “fools” were defined not by the sex they had or who they had it with, according to Hay. Rather, they played particular roles in sustaining certain cultural practices and as repositories of knowledge.

He presented his findings in “The Homosexual and History,” which attempted a dialectical study of the role that those who fell outside socially accepted gender and sex roles had played in the past—and could play in the present and future. Drawing on Marxism’s focus on the overthrow of matriarchy and the onset of male domination as part of the division of labor and the rise of private property, Hay argued that the origins of the oppression of the homosexual was closely linked with the oppression of women.

The advance of agriculture and technology meant surplus wealth could now be produced and accumulated, transitioning eventually into private property. The breakdown of communal society and the rise of the male-centered patriarchal family unit—and the consequent growth of religious and other ideas to support this new economic arrangement—conspired to squash any liberal attitudes that might have existed toward sex and gender expression. The raising of children was also no longer a communal affair, but rather the task of the family unit and a source of exploitable labor. Homosexual relations produced no children, and thus the regulation of such behavior arose in line with the regulation of female sexuality and labor.

Hay’s theorization was still incomplete, but it would be further refined and bolstered by later radical gay activists. Bob McCubbin’s 1976 study, The Gay Question: A Marxist Appraisal, which was put out by the left-wing Workers World Party, remains a touchstone historical document that followed in the Harry Hay tradition.

With an examination of the historical roots of homosexual oppression at least partially begun, Hay gave particular attention to the issues of shared culture and language among homophiles, the word coined by Mattachine to refer to this community in formation. He wrote:

The Homophile common psychological make-up manifests itself in a community of culture so phenomenologically remarkable that it transcends the mechanical barriers of formal language by creating an international behavioral language of its own, in addition to sharing the pedestrian language of each parental community. To be sure, the communities of culture differ in detail from one national community to another. But they are enough alike that no one need be a helpless stranger whatever the port of call.

Essentially, what he meant was that gay people will always find and recognize one another no matter where they are in the world.

Rowland, again playing the Engels to Hay’s Marx, put the theorist’s ideas into a readily digestible form. He told a 1953 Mattachine convention: “We must disenthrall ourselves of the idea that we differ only in our sexual directions and that all we want or need in life is to be free to seek the expression of our sexual desires as we see fit.” He said that “the heterosexual mores of the dominant culture have excluded us,” and as a result, “we have developed differently than other cultural groups.” Rowland concluded that homosexuals had to develop “a new pride—a pride in belonging, a pride in participating in the cultural growth and social achievements of the homosexual minority.”

In developing the Cultural Minority thesis, Hay and his Mattachine comrades were setting the example from which all future radical LGBTQ politics would emerge. From that point on, there would of course be setbacks, reversals, and internal battles, but, in the words of Timmons, the Cultural Minority thesis became “the implicit mode of self-understanding and community organization of Lesbian/Gay communities wherever they exist,” even if its Marxist roots typically went unacknowledged.

Strategy: The Popular Front and the unity of oppressed peoples

Just as Hay drew from his CPUSA experience in establishing the theoretical basis of a gay liberation movement, he did the same when formulating the Mattachine Society’s political strategy. Gay politics, from their beginning, were popular front politics.

Known as “the people’s front” in the U.S., the popular front strategy had been adopted by Communists around the world in the 1930s to combat the rise of fascism. At its core is the idea of broad-based coalition politics, formulated around a couple of key strategic questions. First, it asks what goal, if won, can change the relationship of forces and open up the possibility for advance. Second, it sets out who are the main opponents and possible allies in the struggle to achieve that goal. This means determining who has the self-interest to fight for the goal and assessing their organization, consciousness, and capacity to join in the fight.

The popular front represented Communists’ abandonment of sectarian and doctrinaire “go-it-alone” dogmas which had held that only the organized working class was needed to overturn capitalism and that nothing less than total revolution would do. Racism and other problems would disappear after socialism was won; the class struggle would settle such questions. Instead, with the popular front, the party promoted the notion that change could be won in the here and now through the united efforts of workers, oppressed groups, and anyone who had an interest in stopping the descent into reactionary politics and fighting racism and division. It was the way to alter the balance of forces and open the path to progress.

The popular front represented Communists’ abandonment of sectarian and doctrinaire “go-it-alone” dogmas which had held that only the organized working class was needed to overturn capitalism and that nothing less than total revolution would do. Racism and other problems would disappear after socialism was won; the class struggle would settle such questions. Instead, with the popular front, the party promoted the notion that change could be won in the here and now through the united efforts of workers, oppressed groups, and anyone who had an interest in stopping the descent into reactionary politics and fighting racism and division. It was the way to alter the balance of forces and open the path to progress.

Hay carried the popular front with him into Mattachine. He saw homosexuals as a distinct cultural minority but believed that their social advance rested on building alliances and finding shared interests with others oppressed under patriarchal capitalism.

“We are essentially a group of individuals that have been forced together by society. Society attacks the Homosexuals for their non-conformity in sexual desire and objects completely on the basis of this one characteristic. This attitude would change if society could see the positive side and realize the potential ability to offer a worthwhile contribution,” he told a Mattachine group in 1951.

In the 1930s and ’40s, the popular front established a legacy that extended well beyond the bounds of the Communist Party. The building of coalitions of workers, women, African Americans, Chicanos, youth, immigrants, and eventually the LGBTQ community and others became the standard strategy for progressive change and left-wing electoral politics in the United States, a situation that still prevails to this day.

The tactics and organizing principles of the popular front were also imported into Mattachine. The group was organized much like the broad-based coalition front groups that the Communists had initiated and led in the 1930s. The Los Angeles Anti-Nazi League has been cited as an inspiration for Mattachine, for example. And although some scholars recognize the Freemasons when they look at the structure and social service goals of Mattachine, it is actually more reminiscent of the International Workers Order—a fraternal aid society led by CP members.

Mattachine’s internal system of tiered levels of responsibility and authority showed hints of democratic centralism, the organizing principle of communist parties. There were also provisions for aboveground and illegal structures—a lesson learned from intense periods of anti-communist repression. The group set itself three missions: unify, educate, and lead; Hay saw Mattachine as essentially a vanguard that would raise the consciousness of oppressed homosexuals and move them to action.

The document “Mattachine Society Missions and Purposes” was in some respects the homosexual equivalent of Lenin’s What Is to Be Done?, the pamphlet which laid out the principles for a “party of a new type.” In his document, Hay wrote:

It is not sufficient for an oppressed minority like the homosexuals merely to be conscious of belonging to a minority collective when . . . that collective is neither socially organic in its directions and activities. . . . It is necessary that the more far-seeing and socially conscious homosexuals provide leadership to the whole mass of social deviants. . . . Once unification and education have progressed, it becomes imperative . . . to push into the realm of political action.

The linking of gay equality to other progressive causes was also a priority for the Mattachine founders. The group’s very first action was gathering peace petitions against the Korean War at a gay beach in California.

In the early Mattachine Society, then, we find a group of small-c communist gays who were attempting to organize their emerging community along the lines of a rudimentary Marxist analysis of their oppression and with the tools learned in the fight against fascism. Even though circumstances and prejudices did not allow them to be in the Communist Party proper, Hay, Rowland, and other Mattachine activists were doing communist work and attempting to link up the homosexual cultural minority with others who were oppressed by capitalism and had an interest in fighting it.

Forever a comrade

The groundbreaking role of Mattachine in theorizing gay identity was lost in the fog of, first, anti-communism and, later, the pressures for queer people to assimilate to the standards and social structures of the straight world. As McCarthyite repression intensified, Hay and other radicals were pushed out of Mattachine by anti-communist elements and political moderates within.

They worried that the Marxism of Hay would tarnish their ability to win the toleration of socially conservative heterosexual society. Revolutionary notions of sexual liberation and an overturning of patriarchal gender roles weren’t on the agenda for these timid assimilationists. By the time of Stonewall in 1969, Mattachine was largely seen as a conservative force, sometimes even as a brake on progress. It dressed its gays in suits and ties and its lesbians in dresses and high heels, looking down on the multiracial and working class trans women and drag queens of the street—the “wretched of the earth” in the words of the old Communist anthem, The Internationale.

Hay went on to found other groups to fight the assimilationist trend, and he continued challenging taboos over the decades. He was also an eager advocate of efforts to overcome the male-centered focus of the early movement, supporting lesbians, bisexuals, trans persons, and others as they expanded the boundaries of queer liberation to account for the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality.

But Harry never left behind the Marxism he had learned in the Communist Party USA or the commitment to a post-capitalist world that the party forged in him. According to Timmons, Hay watched the advance of perestroika and reform in the Soviet Union in the 1980s with great hope, but he was saddened by those who wanted to throw out scientific socialism along with the USSR.

But Harry never left behind the Marxism he had learned in the Communist Party USA or the commitment to a post-capitalist world that the party forged in him. According to Timmons, Hay watched the advance of perestroika and reform in the Soviet Union in the 1980s with great hope, but he was saddened by those who wanted to throw out scientific socialism along with the USSR.

“Marxism needs to be revised,” he said in 1990, “based on new scientific knowledge, particularly of human behavior. . . . The underlying methodology will be proved sound.” The science of dialectical and historical materialism that he had studied and taught in the CPUSA remained at the core of his analysis of society.

When leaving the party in 1951, Hay had expressed the hope that “one of these fine days . . . maybe we can all come back together again,” but it wasn’t to be. It was only in 2001, just before Hay’s death, that the CPUSA made an official conversion to openly supporting LGBTQ equality.

Today, the party is a committed fighter in the struggle for queer liberation, with many LGBTQ persons playing key roles among its leadership and membership. It has become a part of the fight for what Harry Hay called the “heroic objective” of the movement way back in 1950: “liberating one of our largest minorities from the solitary confinement of social persecution and civil insecurity . . . and guaranteeing them the basic and protected right to enter the front ranks of self-respecting citizenship, recognized and honored as socially contributive individuals.”

As with so many movements of the oppressed around the world, the theoretical and strategic roots of the queer movement are products of the Marxist tradition. That legacy tells us that the oppression of LGBTQ persons will continue to exist as long as the material conditions inhibiting true freedom prevail. And it tells us that winning full sexual liberation will require winning political, economic, and social liberation for all peoples—it will require socialism.

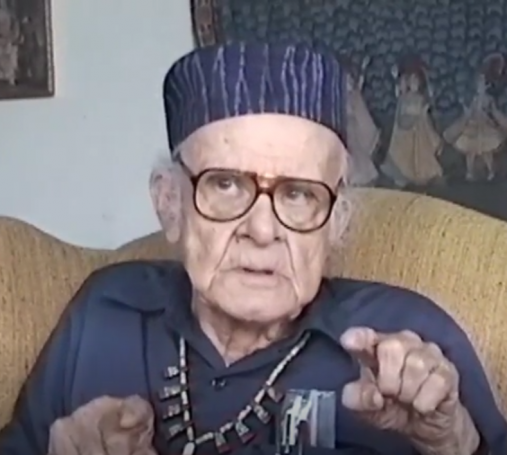

Images: top, Collage: Young Harry Hay photographed by LeRoy Robbins, San Francisco Public Library / Vote Communist poster, 1928, CPUSA Archives / Harry Hay speaking at a demonstration in the 1979, USC – ONE Archives / Cover of May 1959 issue of Mattachine Review; San Francisco maritime strike of 1934, Wikipedia (public domain); Mattachine Society magazine covers, National Museum of American History (CC BY-NC 2.0); Mattachine Society members (Harry Hay, upper left), Jim Gruber (Wikipedia); Harry Hay in 1996, video interview by Shaping San Francisco (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0).

Join Now

Join Now