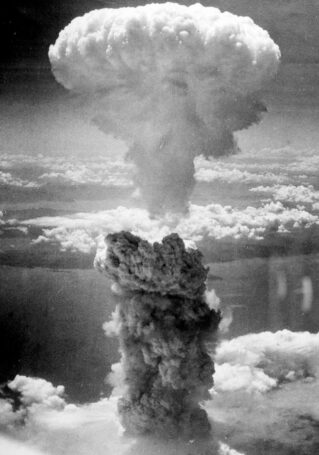

This week is the 76th anniversary of the brutal destruction of Hiroshima. Then and now, the atom bomb attack is hailed for ending World War II and as a triumph of U.S. science and technology. The atom bomb was the most destructive weapon in human history. But within a generation, nuclear weapons would become far more devastating. Hydrogen bombs delivered by long-range bombers or guided missiles launched from thousands of miles away could kill millions of people.

Fifteen years after the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — the first and so far last nuclear attacks — scientists calculated that stockpiles of nuclear weapons in the U.S. and the Soviet Union could potentially kill more than twice the world’s population. The concept is called “overkill.”

How can we understand these developments from their beginning and their meaning for today? The CPUSA uses Marxism-Leninism to understand the past and the present and to prepare for the future. We believe that education and organization are essential for freeing the people from the prison that capitalist social relations create for them. Communists apply Marxism-Leninism in a scientific way to analyze social systems and societies in terms of their economic base and their legal, political, social, and cultural superstructure. The economic base (factories, offices, machines, raw materials, and human labor) interacts with the superstructure (formal and informal laws, rules, codes of conduct and social relations between individuals, families, groups, communities) as both change.

Vladimir Lenin used three components to simplify and clarify Marxism for the masses: materialism, surplus value (profit), and class struggle. The best way to understand the post–World War II world is to apply these three components. Regardless of idealist slogans used by the ruling classes throughout history (such as Woodrow Wilson’s “The world must be made safe for democracy” and Trump’s “Make American great again”), the collective actions of all ruling classes are defined by class-conscious materialism.

The capitalist class in 1945

First, the Second World War was the greatest and most destructive war in history. It was won by a united front of three great allied powers: the British empire on the right, the American republic in the center, and the socialist Soviet Union on the left. This alliance defeated the fascist Axis powers (Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and the Japanese empire), and their collaborator governments throughout Europe and occupied areas of Asia and the Pacific.

Partisan forces, especially the large partisan armies organized by the Communist Party of China, the Communist-led Vietminh in Vietnam, and Communist and left-led partisans in Italy, France, Greece, Yugoslavia, and other countries, played an important role in fighting and winning the war against the Axis powers. Communists and the broad left emerged much stronger at the end of the war throughout Europe, Asia, and the Pacific.

At the same time, major anti-colonial movements in India, Africa, and the Middle East, many of them oriented toward socialism, grew in importance. This was in response to the colonial empires’ policy of treating their “subjects” as inferiors without rights in their own homelands — the same policy the fascist Axis was seeking to impose worldwide.

Post-war aspirations of the U.S. working-class majority

In the U.S., Communists at home campaigned for both Franklin Roosevelt’s Economic Bill of Rights program in 1944 and the building of a United Nations organization that would win the peace. Roughly 33% of the work force had been organized into trade unions. The NAACP and other civil rights organizations had grown substantially by the end of the war. Even with a racist backlash that saw riots against African Americans in Detroit and Mexican Americans in Los Angeles, hopes were high for major victories in the postwar period: a national health system; national legislation for full employment, public housing, and education; and an end to Southern segregation, disenfranchisement, and formal and informal racist policies.

But these goals were not realized after the war. In 1945 the U.S. capitalist class enjoyed super profits, controlling 80% of the investment capital of a devastated world. Its major capitalist competitors, enemy and ally, were either on the brink of bankruptcy or in ruins.

However, for the capitalists, the class struggle was not going so well. Under the New Deal government, the number of workers in trade unions had increased by more than five times between 1933 and 1945, with Communists playing a leading role in organizing industrial unions. Social legislation, the kind associated with socialism in Europe, had all been implemented: minimum wages, unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, public works jobs for the unemployed, and public assistance for the unemployable. In addition, to make matters worse for capitalists as a class, progressive income and corporate taxes had been instituted to pay for the war.

Administration-supported programs that would go further after the war were in the offing: national health insurance, full-employment legislation to be implemented with a full-employment budget, large federal education and housing programs, along with a great expansion of publicly owned utilities modeled after the Tennessee Valley Authority. CPUSA activists in the trade unions and people’s movements were perhaps the most vocal supporters of these programs and were crucial to winning grassroots support for their enactment.

The capitalists in 1945 could either have it all at home and abroad or lose a great deal very soon in a post-1945 world. Most understood that this new world could never return to what it was before the depression and world war: deregulated and nonunionized.

So what could the class-conscious capitalist class do both to regain ground in the class struggle and to foreclose on the tempting assets of their battered and bankrupt major capitalist rivals? The atomic bomb offered one answer.

The twisting road to Hiroshima

An anti-Communist trade union figure, James Carey, of the United Electrical Workers, predicted the future when he reportedly said in 1945, “In this war we fought with the communists against the Fascists and in the next war we will fight with the Fascists against the Communists.” To do that, the plans for postwar reconstruction and peace would have to be abandoned.

Those plans were established at the Yalta Conference (January 1945) of the Allied powers. The U.S. (Roosevelt), British (Churchill), and Soviet (Stalin) leaders had agreed on a settlement for postwar European reconstruction and reparations for the victims of fascist war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Soviet Union pledged to end the war 90 days after Germany’s surrender if the war in Asia had not ended.

Winston Churchill sought to break this agreement and march to Berlin to beat Soviet forces. Roosevelt and the U.S. commander and later president Dwight Eisenhower rejected this policy — Roosevelt, because it would create great conflict with the Soviet Union, and Eisenhower, because he feared the huge U.S. casualties it would bring about, along with prolonging the war by failing to mop up German forces in other regions.

After Roosevelt’s death, Churchill asked the British military to come up with a plan to launch an attack with U.S., British, and former German divisions against Soviet forces in occupied Germany in early July 1945. This fantastic scheme to launch World War III against the Soviets, which the British military called “Operation Unthinkable,” and which no one supported except Churchill, was buried and kept secret after the socialist British Labor Party won a sweeping victory in British elections and Churchill was no longer prime minister.

Following Roosevelt’s death in April and the German surrender, the new president, Harry Truman, dramatically moved away from his predecessor’s policies. First, he accepted Congress’s cancellation of Lend Lease aid to Britain and the Soviet Union, literally ordering U.S. merchant marine ships to turn around in the Atlantic rather than deliver their cargoes immediately after VE Day. Even before the German surrender, he met with Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and demanded that the Soviets immediately withdraw their forces from Eastern Europe. Only his advisors’ warnings that these policies were senseless and destructive led him to tone down his rhetoric.

Truman’s desire was to force the Soviets out of Eastern Europe while retaining U.S. and British forces in Western Europe and using their power to keep influential Communist parties out of power in France and Italy.

The atomic bomb changes Truman’s policy

The U.S. nuclear weapons “Manhattan Project” began in 1942 and conducted research throughout the war. Britain had its own nuclear project, aided by the U.S., and the Soviets, with much more limited resources, were also working on developing an atom bomb.

After becoming president in April 1945, Truman learned about the bomb from Secretary of War Henry Stimson, who called it the most terrible weapon in history. The bomb was tested successfully at Los Alamos in July while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, who was permitted to lead the British delegation even though he was no longer prime minister. Truman informed Stalin of the Los Alamos test and said privately that the bomb was a “hammer” to use against the Soviets in Europe to get them to accept U.S. dictates, and to “equalize” against the Red Army of the Soviet Union and the large anti-Nazi partisan forces in which Communists played a leading role.

Truman’s political advisors recommended the use of the bomb against Japan without warning. But most scientists were opposed to its use, and military and other officials were also skeptical, contending that, given Japan’s position and Germany’s defeat, the war could be ended through negotiation rather than using the bomb. U.S. intelligence, through decoded messages, knew of the division within the Japanese government and believed that the Japanese would end the war if they were permitted to retain their emperor. Truman was also informed of this by British and Soviet sources. Japan had already faced enormous devastation, had seen its air force and navy largely destroyed, and likely faced mass starvation, owing to its collapsed agriculture and closed ports, if the war continued through the end of the year.

Truman’s political advisors recommended the use of the bomb against Japan without warning. But most scientists were opposed to its use, and military and other officials were also skeptical, contending that, given Japan’s position and Germany’s defeat, the war could be ended through negotiation rather than using the bomb. U.S. intelligence, through decoded messages, knew of the division within the Japanese government and believed that the Japanese would end the war if they were permitted to retain their emperor. Truman was also informed of this by British and Soviet sources. Japan had already faced enormous devastation, had seen its air force and navy largely destroyed, and likely faced mass starvation, owing to its collapsed agriculture and closed ports, if the war continued through the end of the year.

Truman’s response was to reassert the demand for unconditional surrender and threaten ” the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland” if the Japanese did not comply. After the Japanese government rejected this ultimatum, Truman ordered the first attack — at Hiroshima, a city of 320,000 people. Eighty thousand were killed, many vaporized by the attack, and another 60,000 perished by the end of the year from radiation injuries or the lack of medical attention. Two days later, not receiving unconditional surrender, Truman ordered a second bomb to be dropped as the Red Army entered Manchuria and Korea. Nagasaki was the second target. Here the death toll was much lower because the bomb landed off-target.

From the atom bomb to a cold war

Truman would say that he did not lose any sleep over his decision. In September 1945, within weeks of the Japanese surrender, the Truman administration launched in Europe and Asia what came to be called “the cold war.” The Truman administration reneged on Roosevelt’s promise of reparations to the Soviets, refused to share nuclear information with the Soviets as part of a plan to bring about a UN-administered nuclear disarmament program, and demanded that the Soviets withdraw from the nations they had liberated in Eastern Europe. The conservative press praised these policies as “getting tough with the Russians,” while they opposed labor, jobs, housing, and price-control policies to bring about reconversion to a peace-time economy.

The Truman administration also used the large surrendered Japanese army in China as a police/military force to prevent the partisan armies led by the Communist Party of China from rapidly sweeping to victory. Finally, the U.S. permitted Japan to keep their emperor and gave the Japanese royal family immunity for their war crimes. Also granted immunity were the Japanese corporations such as Mitsubishi and Nissan, who had profited from Japanese militarist imperialism and would later profit from U.S. cold war policies.

These were the causes and consequences of the Hiroshima attack. Nuclear disarmament and an international peace policy were possible in 1945. That policy remains necessary today after trillions of U.S. dollars were and continue to be wasted in military budgets that produce neither security nor peace.

The documentary Atomic Café presents without commentary the newsreels, radio addresses, and later television clips of the atom bomb and all that followed.

This article first appeared on the New Brunswick Club CPUSA Facebook page.

Images: Hiroshima, National Archives (public domain); Atomic bombing of Nagasaki, photo by Charles Levy (Wikipedia, public domain).

Join Now

Join Now