It took a movement analyzing our conditions and studying our history to say, “Restrictions on abortion and birth control are deliberate actions taken by people who are benefiting at our expense. They’re part of a larger pattern of oppression and exploitation aimed at making our reproductive labor cheap or free.” But instead, our movement has been saying, “This is a very personal decision.”

—Jenny Brown, Without Apology

You bet it’s personal — personal to more than half the population of the United States.

Nearly 170 million cis women, trans men, and non-binary people are personally affected by the country’s restrictions on abortion. According to the Guttmacher Institute, there were 106 new restrictions on abortion in 19 states this year (Nash). That’s the highest yearly number of new restrictions ever, according to their count.

Think about it, 106 new restrictions in just one year.

Since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, states have enacted 1,336 restrictions on abortion (Guttmacher Institute).

So why are we so surprised that Roe could finally go down once the U.S. Supreme Court announces its decisions on the Mississippi and Texas cases? Anti-abortion activists have been chipping away at Roe from its inception.

And make no mistake — all the hand-wringing about a woman’s “very personal decision” doesn’t even begin to address what’s really going on here. As Jenny Brown writes, “Restrictions on abortion and birth control are . . . part of a larger pattern of oppression and exploitation aimed at making our reproductive labor cheap or free” (66). Grieving over the threat to a woman’s “very personal decision” is a distraction. No — it’s a sham, given the fact that what we should really be grieving over is the second-class status of women in this country. Let’s grieve over oppression and exploitation.

The big steal!

The oppression and exploitation of women has its roots in the evolution of the family, according to Friedrich Engels’ Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. It’s impossible to summarize his work, but for the purposes of our discussion, he argued that, before “civilization,” when most societies were communally structured, the woman was equal — if not privileged — to the man. “Among all savages and all barbarians . . . the position of women is not only free but honorable,” due in large part to all the labor they contributed to the community and the fact that descent of children could only be recognized as the female line (Engels).

But natural selection, economic development which resulted in the concept of property/wealth, and social changes shifted the family structure from groups to loose pairs until by the time the Greek civilization appeared, women’s status (what Engels calls the “mother-right”) had significantly declined.

Thus on the one hand, in proportion as wealth increased, it made the man’s position in the family more important than the woman’s, and on the other hand created an impulse to exploit this strengthened position in order to overthrow, in favor of his children, the traditional order of inheritance. This, however, was impossible so long as descent was reckoned according to the mother-right. (Engels)

The solution? Overthrow the mother-right and solidify the transition to monogamy to make clear the line of inheritance through the man.

The overthrow of mother-right was the world historical defeat of the female sex. The man took command in the home also; the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude, she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children. . . . It is the existence of slavery side by side with monogamy . . . that stamps monogamy from the very beginning as for the woman only, but not for the man. And that is the character it still has today. (Engels; author’s emphasis)

More recent history than the birth of civilization provides evidence of Engels’ assertions. In 1869 Pope Pius IX pronounced as murder all abortion from the point of conception. His interpretation of the origin of life wasn’t his only motive for this edict. Lawrence Lader, a towering figure in the abortion rights movement who in 1966 wrote one of the first major books published on abortion, points out that the pope’s decree “followed the rapid emergence of contraceptive practice and the corresponding decrease in the birth rate of France, the largest Catholic country in Europe” (Lader, Abortion, 79–80).

More recent history than the birth of civilization provides evidence of Engels’ assertions. In 1869 Pope Pius IX pronounced as murder all abortion from the point of conception. His interpretation of the origin of life wasn’t his only motive for this edict. Lawrence Lader, a towering figure in the abortion rights movement who in 1966 wrote one of the first major books published on abortion, points out that the pope’s decree “followed the rapid emergence of contraceptive practice and the corresponding decrease in the birth rate of France, the largest Catholic country in Europe” (Lader, Abortion, 79–80).

Abortion was legal in the U.S. from independence for almost a hundred years. During that time, midwives and abortionists performed most of the abortions. But doctors in the burgeoning medical profession pushed back. They began to lobby lawmakers to restrict who could do abortions to medical doctors, effectively cutting down the competition. As a result, state laws restricting abortion and contraception popped up.

But it wasn’t until 1873, just four years after the Pope Pius IX decree and seven years after the end of the Civil War, that abortion was federally outlawed (Brown, 29–32). Casualties from the war totaled more than a million soldiers and civilians. If the U.S. wanted to continue its industrial development, it would have to crank up the birth rate.

The 1873 ban wasn’t just on abortions. All contraceptives and information about sex and reproduction were prohibited. “The federal Comstock Law gave that famous purity crusader Anthony Comstock the ability to raid any bookstore, medical facility, college, office or home to eradicate not just contraceptive devices or abortion elixirs but any knowledge of contraception and abortion” (Brown, 32). Bans on abortion, meaningful sex education, contraception devices plus civilian snitches followed by police at the door sounds a little like Texas’ contribution to today’s Supreme Court deliberations.

Connecting the dots

Today, the overall population in the United States is falling. The number of seniors is growing fast, despite the terrible toll the coronavirus has taken on the elderly, while the birth rate has dropped dramatically since 1950. The decline is even more precipitous with the pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that 2020 saw a 4% drop in the birth rate — the largest yearly decline since the late ’70s.

Is it just the pandemic that fuels the desire to put off making a family? We are suffering from a deep malaise, and not just because of COVID. For at least two decades, younger generations have grown more and more insecure about their futures. The job market is unstable — many couples must work more hours to survive — school debt is crippling, and the cost of health care has exploded. The sheer cost of raising a child makes some couples wonder if having a child is the responsible thing to do.

And climate change looms in the minds of young people, who wonder if they will survive, let alone any children they might bring into the world.

Experts assumed the birth rate would recover after the 2008 recession, but it didn’t happen. Now lawmakers worry openly about economic stagnation and decline. Their solution? More babies.

“House speaker Paul Ryan made headlines for saying, ‘We need to have higher birth rates in this country’ as he prepared to attack Social Security in December 2017” (Brown, 57). His concerns and his solution have been echoed in major news publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. The day may not be far off when lawmakers decide the answer to the staffing shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic is to make more babies. It’s no wonder the attacks on Roe have ratcheted up. We can’t keep the machine running if abortion is easily available. And if making abortion illegal doesn’t do the trick, well, maybe the next step is a Comstock-style assault on birth control.

All of this is outrageous — for a society to look to half its population as potential brood mares to keep capitalism alive. It’s why the abortion rights activists’ justification for abortion as “a very personal decision” distracts, in fact mutes the outrage. A personal decision makes the need for an abortion seem like an individual quandary, not a national disgrace.

Consequences

All sorts of undesirable consequences arise from the capitalist exploitation of women.

A friend tells of a conversation she had with her 19-year-old daughter recently.

She said she wants to go on birth control — not because she is sexually active; she is not. She wants birth control because she doesn’t feel safe in this culture. She wants birth control because she fears Roe v. Wade will be overturned by the Supreme Court. That means if she becomes a victim of rape and as a result a child is conceived, she cannot bear the thought that she would not be able to terminate the pregnancy. Why should she be re-traumatized by being forced to carry the child for nine months, give birth, and possibly be responsible for raising that child?

This young woman is a serious person — she thinks a lot about the consequences of being human. She is self-aware, empathetic, and non-judgmental. She is generous with grace because she has a good sense that people don’t know what it’s like to be in another person’s skin. She likes to dye her hair green, sometimes purple, but she doesn’t believe in YOLO — she contemplates the future. That she needs to think about the possibility of being raped is devastating. But what is really horrifying is that the oppressive, exploitive culture she lives in can rob her of her unique individuality, shackling her to the role of a vagina with legs — a receptacle available to any man who chooses to make a deposit.

By relegating women to the role of breeder, and by endorsing the system that insists on fidelity from women but not necessarily from men, women fall prey, literally, to the entitlement of men. The climate is breathtaking as story after story unfold in news media — stories of men in power taking what they want and when they want it, with little to no consequences for them. No wonder my friend’s daughter doesn’t feel safe. For her, the issue isn’t abortion — it’s being a woman in a capitalist society. In “Capitalism and the Oppression of Women: Marx Revisited,” feminist scholar Martha E. Gimenez writes:

Political emancipation and the attainment of political and civil rights are inherently limited achievements because, though the state may abolish distinctions that act as barriers to full political participation by all citizens, it does not abolish the social relations that are the basis for those distinctions and are presupposed by the very existence and characteristics of the state. (29)

So the liberation of women depends not just on the availability of abortion. The degree to which they can be liberated depends on the needs of capital accumulation.

Opportunity for all?

Capitalism is particularly cruel to poor women and women of color.

- The federal poverty level for 2022 is projected at just under $13,000 a year for an individual and $26,500 for a family of four.

- According to the 2019 U.S. Census, 34 million Americans live in poverty.

- Fifty-six percent were women.

Women of all races earn less than white men. They have fewer career opportunities than white men. And single women head more households than single white men. If a single mom needs an abortion, she faces more and more challenges with each restrictive state law passed.

For women in poverty and for women of color, this is especially true. Nationally, studies show the rate of abortion among poor women is higher than that of women with means. The rate of abortion among white women is significantly lower than that of women of color, attributable to the “systemic inequalities in health care access, insurance coverage, as well as economic and social hardships contribute to racial-ethnic disparities in the abortion rate” (Goyal, Brooks, Powers). One example of systemic inequalities is the Hyde Amendment, which bans government funding for abortion. Medicaid doesn’t cover abortion except in cases of rape, incest, or threat to the mother’s life. That means the woman must save up to pay for the procedure, which often results in delaying the abortion. Early-term abortions are much safer and less expensive than abortions performed in the second trimester. The risk of complications is greater, and complications result in lost time, energy, and wages, not to mention the damage to the woman’s health.

For women in poverty and for women of color, this is especially true. Nationally, studies show the rate of abortion among poor women is higher than that of women with means. The rate of abortion among white women is significantly lower than that of women of color, attributable to the “systemic inequalities in health care access, insurance coverage, as well as economic and social hardships contribute to racial-ethnic disparities in the abortion rate” (Goyal, Brooks, Powers). One example of systemic inequalities is the Hyde Amendment, which bans government funding for abortion. Medicaid doesn’t cover abortion except in cases of rape, incest, or threat to the mother’s life. That means the woman must save up to pay for the procedure, which often results in delaying the abortion. Early-term abortions are much safer and less expensive than abortions performed in the second trimester. The risk of complications is greater, and complications result in lost time, energy, and wages, not to mention the damage to the woman’s health.

Data show that most unwanted pregnancies are unintended, often due to failed contraception. Condoms are effective in protection from sexually transmitted disease, but less so as birth control. More effective contraceptives are more expensive and require visits to the clinic or the doctor — more lost time, energy, and money for a woman who is already struggling to hold down a job, feed a family, manage transportation, and secure affordable housing

Again, poor women of color experience even more burdens, including systemic discrimination, and documented coercive reproductive health policies. There is a long history of forced sterilization of Black and Latina women, and as recently as the 1970s, doctors have lied to women of color about tubal ligation as a way of coercing them to allow the procedure. (https://lawblogs.uc.edu/ihrlr/2021/05/28/not-just-ice-forced-sterilization-in-the-united-states/) So it’s no wonder there is widespread skepticism about the motives of family planning advisors. A paper published in the American Journal of Public Health cites one survey indicating that “42% of Blacks and 51% of Hispanics surveyed believed that the government promotes birth control to limit minorities, compared with only 25% of Whites” (Dehlendorf, Harris, and Weitz).

The same paper examined the effects of a 2013 Texas law restricting the abortion pill, banning abortion after 20 weeks, requiring physicians to have hospital admitting privileges, and placing restrictions on ambulatory surgery center facilities. Comparing abortion data from 2012 to 2015, the authors concluded:

Legislative restrictions on abortion exacerbate the existing health disparities faced by non-White women creating an environment in which one group is more likely to experience later abortion, unintended childbirth, and an inability to achieve personal fertility desires compared to another group. These restrictive policies place already disadvantaged groups at greater risk for potentially worse health outcomes.

It can be dangerous to focus too narrowly on the plight of poor women. Jenny Brown writes that it’s not enough to connect the abortion issue to class power — that the discussion must acknowledge the fight against white supremacy. She writes that the concern over the declining birth rate is not just about economic insecurity. Underneath it is, she writes, is panic over the decreasing birth numbers of white children. She quotes Loretta Ross of SisterSong, who warns that the pressure is on for white women to do their job to make sure whites reign supreme:

Many of the restrictions on abortion, contraception, scientifically accurate sex education, and stem cell research are directly related to an unsubtle campaign of positive eugenics to force heterosexual white women to have more babies. (Ross qtd in Brown, 118)

The message is clear. White women are in the crosshairs and their freedom depends on fighting alongside trans men, non-binary people, and women of color.

Forest or trees?

Some scholars say part of the problem with today’s conversation about abortion rights is that it’s missing a connection to Marxist thought, as many feminists say the work of Karl Marx is irrelevant. Because he wrote little specifically about women, his writing is not helpful. Gimenez suggests that, by dismissing his dialectic, those feminists resorted to examining the system of patriarchy separate from the modes of production. The result is, she writes, that the factors contributing to the origins of patriarchy are perceived as abstract, universal, ahistorical — such as biological differences in reproduction, the need for men to control women, and how labor is assigned according to sex, among other factors. These approaches, she writes, “seem to have severed the links between Marx’s work, feminist theory and women’s liberation” (13).

But it’s Marx’s views on the logic of inquiry, she claims, that are indispensable to understanding inequality between men and women. She writes that Marx “historicizes competitive market relations and their corresponding political and legal frameworks by identifying the capitalist coercive (i.e., independent of people’s will), unequal and exploitative relations of production underlying the sphere of ‘Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham’” (18).

Using the same approach, Gimenez argues, this logic of inquiry helps theorize the elements and forms that underlie the lack of equality between men and women:

Just as the relations between social classes are mediated by people’s relationship to the means of production (the material basis of the power the owners of the means of production exert over the non-owners), the relationships between men and women under capitalism are mediated by their differential access to the conditions necessary for their physical and social reproduction, daily and generationally. (18–19)

So, at the core of the oppression of all women in the U.S., a capitalist society, is the need of the oppressor to exploit a woman’s ability to produce children. Dismissing this understanding of the oppression and exploitation of women can cause the defense of abortion rights to be fragmented and eventually diluted at exactly the time when the objective should be clear — remove abortion from the law.

It’s states’ rights, stupid!

A lot of people argue that the assault on Roe is really about which governmental entity should be restricting abortions — the feds or the states. This summer, a dozen governors signed a friend-of-the-court brief calling for the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down Roe and “return[ing] to the states the plenary authority to regulate abortion without federal interference [to] restore the proper (i.e., constitutional) relationship between the states and the federal government.”

When I was a kid, history books suggested the Civil War was not about slavery but about states’ rights. Tell that to a Black woman today and see how it flies.

For nearly 50 years, we’ve been kidding ourselves thinking Roe v. Wade protected us from being forced to turn over our reproductive labor to the state all the while state legislatures whittled away at that protection. Thirteen-hundred thirty-six state-imposed restrictions on abortions is evidence that the law cannot and will not protect women. Roe led us to believe — mistakenly — that the right to “this very personal decision” should be bestowed by law — federal or state. It shouldn’t.

Abortion is a medical procedure not a crime. If it’s a crime, then let’s also outlaw vasectomies, tubal ligations, and even hysterectomies.

No? Well then, let’s just stop all this nonsense about reforming the laws that pretend to regulate abortion but ultimately criminalize it.

We need to repeal the laws — all of them.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Sources

Brown, Jenny. Without Apology: The Abortion Struggle Now (New York: Verso, 2019).

Dehlendorf, Christine, Lisa H. Harris, and Tracy A. Weitz, “Disparities in Abortion Rates,” American Journal of Public Health 103, no. 10 (2013).

Engels, Frederick. Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Marxists.org.

Gimenez, Martha. “Capitalism and the Oppression of Women: Marx Revisited,” Science & Society 69, no. 1: 11–32.

Goyal, Vinita, Isabel H. McLoughlin Brooks, and Daniel A. Powers. “Differences in Abortion Rates by Race,” Contraception 2, no. 2 (2020).

Guttmacher Institute, “U.S. States Have Enacted 1,336 Abortion Restrictions,” Infographic, October 1, 2021.

Lader, Lawrence. Abortion (Boston: Beacon Press, 1970).

Nash, Elizabeth. Guttmacher Institute, “U.S. States Enacted More than 100 Abortion Restrictions, October 4, 2021.

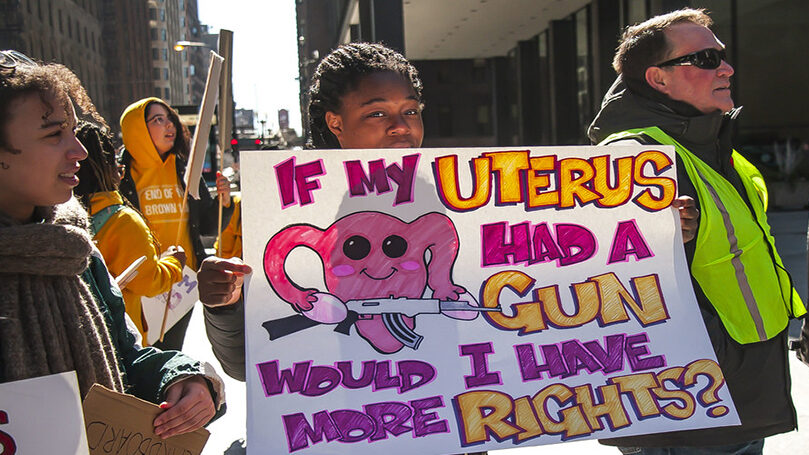

Images: “Pro-choice Activists Interface With Pro Life Rally ( Rally For Life)” by infomatique (CC BY-SA 2.0); “Pro Choice Rally and March” by cj171 (CC BY 2.0 ); “Pro-Choice Rally and Press Conference Chicago Illinois 3-4-20_5573” by www.cemillerphotography.com (CC PDM 1.0); Stop the War on Women, “img_0533” by steevithak (CC BY-SA 2.0 ); “UBC pro-choice rally” by JonathanIchikawa (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Join Now

Join Now