Rodney L. Hurst, Sr. was five years old when he entered kindergarten.

At 11, he joined the Jacksonville, Florida Youth Council of the NAACP.

Five years later, at 16, he took a bold step into the Civil Rights Movement as one of the leaders of peaceful “whites only” lunch counter sit-ins in downtown department stores. When the KKK had enough, hundreds of white men ended the protest, descending on downtown Jacksonville in a violent display. The episode was called “Ax Handle Saturday.”

The killing of Trayvon Martin 10 years ago shone a light on racism in Florida. And in 2020, the Southern Poverty Law Center tracked 68 hate groups (including KKK chapters) in Florida. This hate has a history, and it runs deep. Between 1900 and 1930, more black people per capita were lynched than in any other state. The Florida Historical Society notes that “a black person was almost twice as likely to be lynched in Florida as Georgia, and seven times more likely in Florida than in North Carolina.” Jacksonville was one of the most segregated cities in the South.

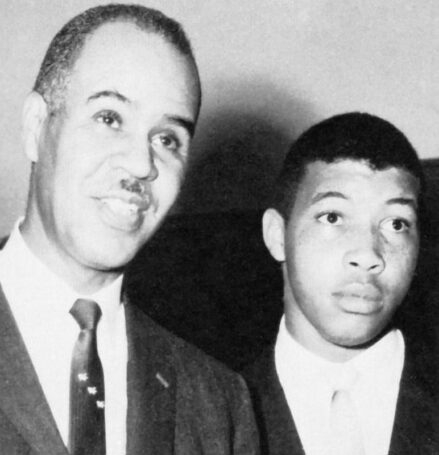

This was the suffocating climate in August of 1960, when Rodney L. Hurst was catapulted into the cause. His junior high school history teacher, Rutledge Pearson, was his inspiration. In Hurst’s book, It Was Never about a Hot Dog and a Coke®!, he writes that his awakening started on the first day of class when Pearson gave instructions about the course text approved by the segregated Duval County School system. “The authors are Robert Johnson and Martin Richards. Published in 1953, it has 352 pages. LEAVE IT HOME!” (Pearson qtd. in Hurst, p. 28). Pearson was determined that revisionist history had no place in his classroom.

The NAACP was the heart of the civil rights movement in Jacksonville, and Hurst was in the center of it all. With Hurst’s leadership, the Jacksonville Youth Council of the NAACP embarked on a campaign of peaceful protest, organizing Sunday appearances at the services of whites-only churches, boycotts of specific businesses (called “selective buying programs” to avoid legal challenges), and, of course, the lunch-counter sit-ins (153).

According to Hurst’s personal account of Ax Handle Saturday, his group of teenagers targeted five downtown department stores including Woolworth’s, W.T. Grant, Kress, and McCrory’s. These stores, according to Hurst, were among the “vestiges of segregation that openly insulted Blacks daily” by accepting the money of a Black shopper at one counter but refusing at another — specifically the “whites only” lunch counter — 84 seats in an area enjoying bright windows (53). Black shoppers could eat lunch only if they walked to the very back of the store to the “Colored lunch counter” — 15 seats and no windows.

According to Hurst’s personal account of Ax Handle Saturday, his group of teenagers targeted five downtown department stores including Woolworth’s, W.T. Grant, Kress, and McCrory’s. These stores, according to Hurst, were among the “vestiges of segregation that openly insulted Blacks daily” by accepting the money of a Black shopper at one counter but refusing at another — specifically the “whites only” lunch counter — 84 seats in an area enjoying bright windows (53). Black shoppers could eat lunch only if they walked to the very back of the store to the “Colored lunch counter” — 15 seats and no windows.

At the time, demonstrators in more than 100 cities across the country were staging lunch counter sit-ins. Many department stores dealt with lunch counter sit-ins by shutting down service. The result was not only lost revenue from white lunch-goers, but also from having to throw out already-cooked food and fresh food that couldn’t be stored. As Hurst writes, “Human dignity and respect would be our fundamental focus, along with making segregation extremely expensive” (55).

Students — mostly from junior and senior highs — had been staging protests in department store lunch counters for a couple of weeks. In small groups and dressed in their “Sunday best,” the students sat at “whites only” counters. They were polite. They were well-behaved. And they didn’t react to the threats, taunts, and slurs hurled at them by agitated white people demanding that they leave. Some students were stuck with pins or other sharp objects. Even the kicking and shoving could not provoke the students. Nobody got violent.

Notably absent from the scene were representatives of the white news media. Even more disturbing, considering the potential for racial confrontation, uniformed members of the Duval County Sheriff’s Office were nowhere to be seen. If police were there, they were undercover.

Early on in their protest, the Black demonstrators were joined by a white college student, who immediately became a target of white racists. The NAACP received an anonymous tip that 25-year-old Richard Charles Parker was in danger. One day, as the students sat at the Woolworth lunch counter, a group of white construction workers, angry about the regular disruption of their lunch hours, gathered behind the students, paying particular attention to Parker. Some of the workers carried rope and various construction tools. Hurst writes he was convinced the construction workers would have lynched Parker that day. But protection came from an unlikely group.

Today, we might call the “Boomerangs” a gang. Hurst acknowledges that the group of poor, young Black men were not afraid of violence, which is why they didn’t participate in the non-violent protests. But they were watching. And the day Parker came close to death, the Boomerangs showed up. Despite pleas to leave the counter with the protection of the Black gang, Parker refused. In the end, the Boomerangs physically removed him, walking him away from danger.

Things were different on August 27th. A Saturday. Shoppers began to see an unusual number of white men on the streets, carrying ax handles. When one police officer, blocks away from Woolworth’s, asked a group of the men why so many had ax handles, they shrugged. Calling it a coincidence, they guessed it just happened that those who needed new ax handles all decided to shop that day. Hurst writes that members of the Jacksonville Youth Council were alert to the “coincidence.” They even considered calling off their protest since that day had come on the heels of Parker’s close call. Regardless, they voted unanimously to continue their demonstrations — they would simply go to a different store three blocks away. “Our determined courage overcame our healthy fear” (71).

Hurst writes that members of the Jacksonville Youth Council were alert to the “coincidence.” They even considered calling off their protest since that day had come on the heels of Parker’s close call. Regardless, they voted unanimously to continue their demonstrations — they would simply go to a different store three blocks away. “Our determined courage overcame our healthy fear” (71).

Store officials chose to close and turn off all the lights. As the students left, they saw in the distance a hostile hoard of white men brandishing ax handles and ball bats running toward them. They were slashing and flailing at anyone who was Black — protesters and bystanders alike. The attack was brutal. News accounts say more than 50 people were injured. Many of them weren’t even protesting. Not one officer of the law was there to intervene.

Word spread quickly in the Black community, and within the hour, a large group of African Americans made their way toward downtown. Then, and only then, Hurst writes, did the police appear in full force coming from everywhere. Unfortunately, they were too late to stop the riots that followed.

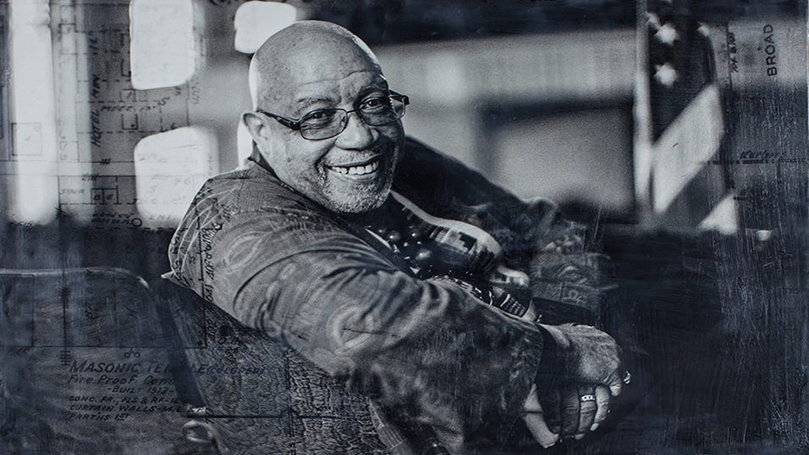

It’s hard to imagine a 16-year-old in the thick of all the chaos, much less one who led the non-violent sit-ins. And Rodney Hurst makes clear in his book that the Youth Council received guidance from the adult chapter of the Jacksonville NAACP. But Hurst clearly learned early on that freedom comes with a cost. His quest for dignity and respect became his calling. In the 60 years that followed, he has been a constant in what he calls “the struggle.”

Today, he is a Black historian, veteran of the U.S. Air Force, and an author of three books. He’s also a terrific grandfather. He is quick to point to the many people in the First Coast of Florida who have spent a lifetime fully engaged in what he calls “the struggle.” He is one of many who left a permanent mark on Jacksonville, emerging as the quintessential community servant. He served two terms on the Jacksonville City Council. He was a member of the Jacksonville Civil Rights Task Force and chaired the sub-committee that created a civil rights time line for Jacksonville, which the city council codified. To this day, he speaks extensively on civil rights, Black history, and racism. He is an adviser to the Center for Urban Education and Policy at the University of North Florida.

One of the four books he wrote was the basis for a PBS documentary on Ax Handle Saturday. His most recent book, Never Forget Who You Are: Conversations about Racism and Identity Development, co-authored by Dr. Rudy F. Jamison, Jr., tackles complex issues. The national website and book reviewer Readers View named it the 2021 Nonfiction “Book of the Year” and its 2021 Grand Prize Winner.

One of his books is called Unless We Tell It . . . It Never Gets Told! That is perhaps one of his greatest legacies — a lifetime of telling it so it gets told.

Source: Rodney L. Hurst, It Was Never about a Hot Dog and a Coke®!, Livermore, CA: WingSpan Press, 2018.

Listen to Hurst’s account of Ax Handle Saturday on this podcast. The Jacksonville Civil Rights Timeline can be found at tinyurl.com/y9wh7kvv.

Images: Top, Rodney L. Hurst; Roy Wilkins, national director of the NAACP, and the young Hurst; White men wielding ax handles on their way to attack civil rights protesters. Images from RodneyHurst.com.

Join Now

Join Now