Jennifer Abruzzo, the current General Counsel for the National Labor Relations Board, recently released “Memorandum GC 21-04” for distribution to the leadership of the Regional Board offices she is responsible for overseeing. While this release went largely unnoticed by broader society, it made significant waves within the labor community, as it is seen to indicate a relatively aggressive pro-worker orientation for the next few years.

Abruzzo noted that while these regional offices can and should continue to resolve the bulk of cases with limited oversight from headquarters, she identified a few important “areas that compel centralized consideration.” The document functions as a “roadmap” for decisions she feels need to be revisited.

A more comprehensive overview of the memo can be found here, but one area that should jump out for Party members is the focus on revisiting questions around “concerted activity protections” contained within Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). “Concerted activity” is where two or more workers engage in “collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection” related to their conditions of employment. Crucially, all workers covered by the NLRA have these protections, unionized or not. This is the legal basis for workers being able to engage in all sorts of organizing activities, such as wearing union buttons on the job, discussing union and workplace issues with coworkers, or delivering a petition of issues to management. These protections are relatively expansive and cover much more than most workers are aware.

Section 7 protections are specifically intended to protect workers while organizing in their workplaces. Any violations of Section 7 rights allow workers to file an Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charge with the NLRB.

Unfair Labor Practice cases are notoriously weak, lacking significant penalties or enforcement mechanisms. However, one of the most important aspects of ULPs is that as soon as one is filed, it triggers protections for ULP strikes. These strikes are constrained in some important ways, but they also carry significant protection by forbidding employers from firing, disciplining, or permanently replacing striking workers.

ULP strikes formed the backbone of the Fight For 15 movement, allowing fast-food workers all around the country to go on one-day ULP strikes. Most employers and management lack even a basic understanding of Section 7 rights and so end up violating them constantly. Any flippant statement about eliminating tips, a demand that workers remove union buttons, or a threat to close a workplace to avoid a union all constitute ULPs.

However, the law is never about just the black ink on paper; it is always a function of the balance of forces that are struggling to turn legal interpretations in their favor. The election of Trump marked a major shift in the balance of forces against the working class. Trump stacked the National Labor Relations Board with aggressively anti-worker administrators and began a mind-spinning assault on how the Board interprets Section 7 rights.

This is one of the key reasons Fight For 15 was significantly weakened over four years of the Trump administration. The dramatic erosion of Section 7 rights did not destroy the movement, but it did make it significantly riskier to feel confident exercising those rights and relying on protection by the law while engaging in ULP strikes.

Abruzzo’s memo indicates that the struggle of low-wage workers in the fast-food and retail industries will be able to begin again ramping up its assertiveness and militancy on the shop floor, likely including ULP-protected strikes. Membership across the Party should take these developments into consideration when thinking about how to respond strategically.

A Transformation at the Base

The strategic line for most of the CPUSA’s history has been to concentrate on the basic industries of the national economy: steel, auto, energy, and so on. This strategy had a two-fold function: 1) to implant the Party in the large production factories driving the national economy where thousands of workers were concentrated at a single workplace; 2) to fuse together the constellation of ethnic and language groups that constituted the CPUSA at its birth.

This strategy held well during the era of Fordist mass production. However, this industrial model came under sharp assault in the mid-1970s as the New Deal coalition collapsed and a new neoliberal consensus took hold. Many of the basic industries were stripped bare by predatory finance monopoly capital and outsourced to areas that offered low labor costs. Key industrial cities like Detroit, Cleveland, Oakland, and many more saw their local economies collapse and working-class residents flee to seek out other opportunities.

From the wreckage of the Fordist industrial model arose today’s “service-oriented” economy. Instead of large industrial factories housing thousands and thousands of workers, workplaces containing only dozens or perhaps a couple hundred workers have proliferated. Where large industrial employers still exist, their degree of monopoly concentration, connection to Wall Street financial credit, and access to global markets have given them tremendous leverage to defeat striking workers and block any new pro-worker labor legislation.

Several years ago, the Party began to question industrial concentration on the basic industries as its core strategy in order to develop a strategy to replace it. This shift makes sense based on some important considerations.

The rise of neoliberalism has been driven by the liberation of finance capital from any geographic constraints. Outsourcing became a key weapon in breaking up and suppressing the biggest and strongest unions concentrated in manufacturing. Even strong and militant strikes can be broken relatively quickly and easily with the extensive financial credit available today, plus the ability to close factories and ship them to developing nations.

This development also influences how to understand the relationship between “economic” and “political” struggles today. If strikes can be defeated through outsourcing, then the political struggle to impose political and legal limits on the outsourcing of capital becomes more important. Such limits would constitute a major shift in the balance of forces for workers located in the manufacturing sector.

However, workers in the basic industries face two obstacles in the fight to limit the weapons of finance monopoly. On one hand, due to the technical explosion in automation, these industries are no longer home to thousands and thousands of workers. Take for instance the fact that there are more employees working for Arby’s today than all those employed in the entire coal mining industry.

Further, these fewer basic industry employees are geographically concentrated in only a few areas. Gone are the days of manufacturing operations dotting the landscape, giving life to communities outside a few metropolitan core areas. Today “the service sector comprises the largest portion of employment in both metro and nonmetro economies overall.”

The racial and gender composition of the service sector is also important to consider. Women outnumber men in the food service sector by about 2-to-1, where the average annual salary is about $22k/year. Of the almost 10 million retail workers in the US, the US Census Bureau reports that:

- Retail workers are younger. Over half of all retail workers were ages 16 to 34.

- Women were more likely to work in retail jobs. About 56.5% of retail workers were women, compared with 43.5% who were men.

- Black and Hispanic people were overrepresented in retail work. Black people comprised 12.5% of the retail workforce compared to 11.4% of the total workforce; Hispanic people were 18.7% and 17.5%, respectively.

- Retail workers were less likely to have a bachelor’s degree or more. In 2018, 18.1% of retail workers had a bachelor’s degree or more, compared with 35.2% of all workers.

- Retail workers were more likely to live in poverty. In 2018, 10.1% of retail workers lived in poverty. In contrast, 6.0% of all workers lived in poverty.

- Retail workers were more likely to have Medicaid. In 2018, 15.3% of retail workers had Medicaid compared to 9.0% of the total workforce. Medicaid is a federal and state program that provides health coverage for low-income people.

Of these retail workers, 1.3 million of them work in grocery stores, with an additional 865,000 working in “general merchandise stores.” Pay breaks down along predictably discriminatory lines, with women making less than men and non-white workers making less than white workers. The median earnings for these 10 million retail workers — white and non-white, men and women — all fall below national median earnings. Only frontline supervisors come near the threshold to afford a one-bedroom apartment in 93% of US counties.

Small Enough to Win, Big Enough to Matter

This indicates that the center of gravity today has moved to the service sector of the economy. The total number of retail plus leisure and hospitality jobs alone exceeds the entire total of workers in the entire goods-producing sector by over 12 million workers. If we include logistics and warehouse workers involved in the retail and hospitality supply chains, the numbers go up even further.

There are real obstacles to organizing this sector. Permanent worker “churn” is an integrated part of the model for low-wage employers in the service sector, from fast food to Amazon. Short-run employment is expected as workers burn out, quit, and then move to another terrible service job where the cycle is repeated.

This makes committee building, a core aspect of organizing, exceedingly difficult. Organizing committees are fundamental building blocks of the modern union election campaign. Today, the focus of these committees is usually on gathering union authorization cards as quickly as possible to trigger an NLRB recognition election. These cards are usually gathered under an attempted cover of secrecy, and as quickly as possible before the boss discovers the campaign and begins trying to bust the union drive with illegal tactics like firing leaders or intimidating workers with lies.

This strategy is often little more than a necessary evil, since businesses now simply factor in illegal anti-union activity as a cost of business, a much more modest cost than a successful unionization drive. If companies were less able to break labor law with utter impunity, the secrecy of most modern union drives would become more of an impediment than an advantage.

This emphasis on quickly and quietly gathering authorization cards means most workers today are expected to take the benefits of unionization largely on faith. With union density so low, most workers have no direct experience whatsoever with the labor movement, much less experience with the benefits of unionization. Workers are often making the decision to support an organizing drive or not based on little more than the strength of arguments from either side of the question. Secrecy can also foster the misconception that unions are somehow illegal (especially in “right-to-work” states) or that the union is asking the worker to do something illicit that should be kept concealed. This starts organizing attempts at a steep disadvantage.

Abruzzo’s proposed changes to Section 7 doctrine would include reversing notorious Trump-era decisions, such as increased restrictions regarding wearing union buttons, but also expand rights beyond the workplace to include political and social justice issues that have a “nexus” with workplace conditions. These changes allow workers to have more confidence fighting around workplace issues like health and safety concerns, as well as broader issues around social justice. An example of this can be seen in the NLRB’s recent ruling around Black Lives Matter buttons being worn by Kroger workers in Seattle.

This dramatic expansion of Section 7 rights will apply to all workers covered by the National Labor Relations Act, allowing them to fight more effectively and safely around day-to-day issues without having to go through the expensive and difficult process of a full union election. These issue-by-issue fights around things like workplace safety, scheduling, pay, or anything else sharing a nexus with workplace issues will allow workers across the country to cut their teeth on militant organizing that can demonstrate the cumulative force of workers united and organized on their own terms, for their own interests, depending on their own rank-and-file power.

There is no silver bullet to the crisis of the labor movement. These NLRB shifts around Section 7 rights will likely do little to stem the churn at these low-wage workplaces in the short term. However, this churn could encourage the spread of organizing knowledge and culture as workers gain experience and familiarity with the concrete benefits of militant workplace organizing and move throughout the low-wage workforce.

Further, the Trump years saw the appointment of many ultra-right jurists to the federal court system. While the total number of judges Trump was able to appoint is lower than other recent presidents, the judges he did appoint flipped the balance to favor the ultra-right in three of the 13 federal appeals courts: the 11th, the 2nd, and the 3rd Circuit courts specifically. Andrew Strom recently analyzed a nakedly anti-worker ruling by the 11th Circuit court which consists of three Trump judicial appointees. The federal courts will likely present a serious obstacle to the new NLRB rules.

The point here is not that these changes at the NLRB will lead to a quick return to the relatively stable, firm-by-firm elections and bargaining environment that preceded the neoliberal turn. They do not negate the need for comprehensive labor law reform; the PRO Act remains a fundamentally necessary step in that reform process. They don’t negate the need to defeat the ultra-right and its monopoly capitalist backers. They certainly don’t negate the need to win Bill of Rights Socialism and the establishment of working people’s power. The point is that these NLRB changes can create space for independent, rank-and-file struggle right now. We cannot see them as solutions to our problems but as a hard-won improvement in the possibility of raising our own fighting initiative.

The Politics of Class Struggle

This sea change is a sharp rebuke to the “pox on both houses” tendency we see within the modern socialist movement. Without the defeat of Trump in 2020, not only would these limited but positive changes have been impossible, but the deepening of the anti-worker labor law regime would also have been inevitable. While it is obviously true that the election of Biden is not a solution to the myriad problems facing the working class at home or the struggle against imperialism abroad, this misses the point entirely.

Working-class and progressive forces are fighting to emerge from the dark decades of neoliberalism and must carve out any space available to strengthen that fight. It is less important how limited this space may be right now due to the historical balance of forces; what matters is that we have that much more space to fight, on the shop floor and on our own terms.

These limited gains must be used to continue to expand the space available to wage our class struggles, including the struggle to secure union recognition and stable bargaining contracts. This legal space, however, can only be won through political struggle at the ballot box. Shifting concentration from basic industries to the service industries allows for militant worker votes to be distributed more broadly than in the core metro areas. While increasing the voter turnout of workers within these core cities may be able to increase the quality of the representatives through primary challenges and nonpartisan local elections, it can do little to increase the quantity of pro-worker representatives within legislatures more broadly. Without this increase in the quantity of more politically dependable pro-worker representatives sitting in legislative office, an increase in quality alone can do little more than produce nobler defeats at the state and national level. Basic arithmetic presents us with this inescapable political reality.

These limited gains must be used to continue to expand the space available to wage our class struggles, including the struggle to secure union recognition and stable bargaining contracts. This legal space, however, can only be won through political struggle at the ballot box. Shifting concentration from basic industries to the service industries allows for militant worker votes to be distributed more broadly than in the core metro areas. While increasing the voter turnout of workers within these core cities may be able to increase the quality of the representatives through primary challenges and nonpartisan local elections, it can do little to increase the quantity of pro-worker representatives within legislatures more broadly. Without this increase in the quantity of more politically dependable pro-worker representatives sitting in legislative office, an increase in quality alone can do little more than produce nobler defeats at the state and national level. Basic arithmetic presents us with this inescapable political reality.

Low-wage service workers have a notoriously low rate of voter turnout. Union membership, especially active union participation, tends to increase voter turnout rates. A study by Richard B. Freeman in 2003 identified the significant number of low-wage workers who are not in unions but hold pro-union sentiments as the most likely place to increase pro-worker voter turnout. This is confirmed by a 2020 Guardian article. Both Fight For 15 and the Poor People’s Campaign have been working hard to turn this knowledge into action.

There is an organic link between the struggles on the shop floor and at the ballot box. Rather than separating workplace organizing from political organizing, political action becomes one more day-to-day activity that workers include in their Section 7 protected struggles that happen year-round. One of the most serious limits to traditional GOTV strategies is that it occurs in a relatively compressed time leading up to an election and then vanishes almost entirely as soon as the votes are cast. Since Section 7 fights can and should go on almost constantly, though with unavoidable ebbs and flows, these fights provide an opportunity to consistently link shop floor fights with political fights in the minds of low-wage workers. The small but important gains that Section 7 fights can win are tightly connected to who is appointing members to the NLRB.

“Protracted People’s Class Struggle”

This strategy has much in common with a “guerilla” form of class combat. Rather than focusing on frontal assaults to win union elections like in Bessemer, we build our forces by winning small but significant victories on an ongoing basis and distributed widely across the country. This “arms and trains” our forces to increase our capacity to win more significant victories more frequently. It is hard to imagine the current balance of forces between capital and labor as anything other than “asymmetrical.”

This is not to say the traditional basic industries are no longer critical to building worker power and eventually achieving a successful transition to socialism. Rather, it is a strategy where basic industries will be “encircled” by workers in the retail, hospitality, logistics, and other industries within the service sector. As these forces grow in both quantity and quality through hard-won experience in struggle, more and more gains will be possible at the political level, including passing serious labor law reform like the PRO Act. This would represent a significant shift in the balance of forces and finally reopen the basic industries to an aggressive organizing push without the threat of political retribution from monopoly-dominated legislatures.

One of the most important lessons our Party can learn from the history of the Chinese revolution is a willingness to break with old orthodoxies. The Soviet leadership, committed to an “orthodox” view of socialist revolution, pressed the Chinese Communists to focus their efforts on the urban industrial proletariat, even when the conditions did not seem to bear that out. This was confirmed by the Nationalist massacre of Communist forces in the cities, leading to the Long March into the countryside. It was through this process that the CPC developed the concept of encircling the urban core by organizing the peasantry and agricultural proletariat in the countryside, which led the Chinese people to one of the most significant victories in world history.

This decentralized, asymmetric strategy can be combined with the important lessons our Party learned in the 1930s. Foremost among them was that “the Left wing must do the work.” The Young Communist League is especially well-positioned to initiate this strategy. Service sector employment is widely distributed, suffering an acute labor shortage, and open to young people early in their working life. Many Party members are already working in service industries. This strategy allows Young Communists to gain practical experience that will strengthen both the CPUSA and the broader labor and democratic movements in the long term. Many of our most heroic leaders, including Henry Winston, got their start organizing the working class in the 1930s by joining the Young Communist League.

The reestablishment and reinvigoration of our Party’s Labor Commission is also increasingly well positioned to play an important role, linking our veteran members — with years, often decades of experience in militant, hard-nosed, shop-floor class combat — with our energetic young comrades. The decentralized nature of this strategy can be met with the strategic use of the internet and digital communication tools to provide critical support to young workers beginning to learn the ropes themselves, such as the training webinars it has been organizing.

The Connecticut District of the Party also demonstrates an important way this strategy could utilize the People’s World. Their district has been building grassroots clubs through “years of circulating our press door-to-door initially with the printed People’s World and now with our four-page paper in these selected neighborhoods.” This consistent, grassroots circulation helped build durable relationships based on trust. This method can be expanded to include service-sector workplaces by distributing People’s World on a consistent shop-by-shop basis.

The CPUSA is on the cusp of a historic renaissance, but it needs a practical strategy to meet the moment. Service-sector concentration meets that moment in a practical, flexible way, building off lessons both in the US and the international Communist movements. It cannot be sectarian, drawing lines that exclude other worker organizations like the AFL-CIO or the Emergency Worker Organizing Committee, which was initiated as a joint project between DSA and UE, or other democratic movements like the Poor People’s Campaign. Rather, it must allow our Party to add the Communist Plus to the broader movements in which it must be rooted. It expands the militant worker base, increases low-wage voter participation geographically, and develops the practical consciousness of the working class on the shop floor and at the ballot box.

Jennifer Abruzzo’s memo will not save us. It is only a small space that we can fight to save ourselves, but only if we recognize the opportunity and seize it with all the strength and courage we can muster. As history has shown time and time again, a humble but committed start is all the Communists need to change the world.

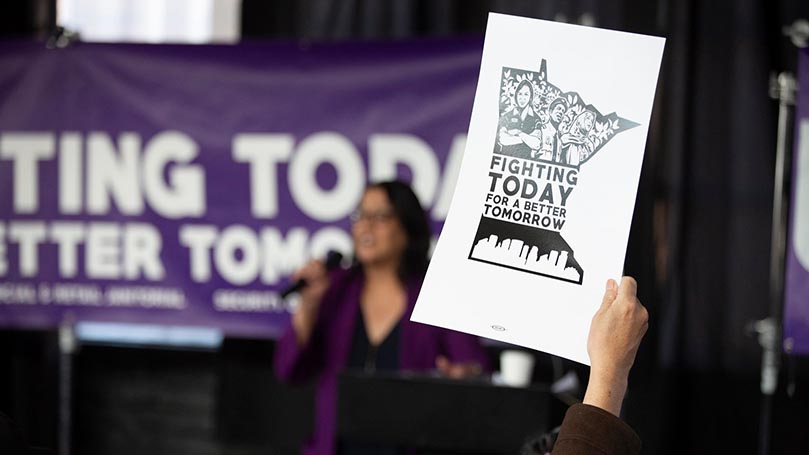

Images: top, SEIU Local 26 (Facebook); Fight For 15, SEIU (Facebook); Closed Lordstown plant, raymondclarkeimages (CC BY-NC 2.0); UFCW picket, UFCW Local 21 (Facebook); Get out the vote, UFCW 21 (Facebook); Standing together, SEIU Local 503 (Facebook).

Join Now

Join Now