“It is clear the people want to challenge the oppressor on the grounds they choose, not on those chosen by their enemy,” wrote Henry Winston in 1971. The Black Panther Party had just undergone a factional split, culminating in the departure of Eldridge Cleaver and his followers and the adoption by Huey P. Newton of a new strategic orientation. Newton’s new strategy de-emphasized political struggle in favor of economic self-preservation, awaiting the day when people would be ready to engage in armed revolutionary action. Winston was sharply critical of both Cleaver’s “catastrophic” strategy of immediate armed struggle and Newton’s “survival program,” which foreclosed the possibility of building a mass struggle to end racist oppression. He contrasts both of those programs with Dr. King’s turn toward the working class and economic justice in the years before his death. The following is excerpted from Winston’s 1971 article, “The Crisis in the Black Panther Party.”

When [Huey] Newton advocated guns and a defensive strategy as the solution for Black people, he was wrong on both counts. Not only did the people refuse to relate to the gun, but they also rejected the concept of a defensive strategy. Black people have been warding off attacks for 400 years. They want and need an offensive strategy to build a great popular movement to end racist oppression.

In his concept of self-defense, Newton endeavored to respond to the oppression of his people. however, this concept excluded the masses of the people from their own liberation struggle. It involved the idea of an elite few acting for the masses–in fact, supplanting them.

[…]

“There Go My People”

It is worth recalling that in the same period when the Black Panthers came on the scene, others were also seeking new directions, notably Martin Luther King.

During the Montgomery bus strike in 1955, King had said, “There go my people. I must catch up with them.” More than a decade later and at a new turning point, King was still motivated by these sentiments. Unlike the Panthers, he did not misread the mood of the people in this new phase, often called the “post-civil rights period.”

It had become apparent to King that an offensive strategy of new dimensions had to be built. The new situation required the continued and even expanded participation of church and middle-strata forces, including students and professionals, Black and white, that had predominated in 1954-66. But King saw that the basis for regaining the offensive was working class strength moving in coalition with the middle class forces. He now directed all his efforts toward involving the working class in a higher level of struggle with the Black liberation movement–and with the poor and oppressed.

The Communist Party welcomed this historic revolution in Dr. King’s leadership, and wholeheartedly supported his efforts to bring about a new strategy and a new alignment of forces. The Communist Party saw this as a profoundly important development, even though Dr. King had not yet demonstrated a full understanding that an offensive strategy to end class exploitation, racist oppression, and war demands not only the strength of the working class, but also the leadership of the working class–Black, Brown, Yellow, Red, and white–guided by the science of socialism. It was clearly evident, however, that long before he was assassinated, King had already begun to move toward an anti-imperialist position.

King was also keenly aware of the dangers that faced the movement. For instance, in his historic address–just two months before his death–at the Freedomways memorial meeting for Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois, King warned that racism and imperialism could not be fought with anti-Communism. In addition, his words about Du Bois carried an all-important message for today’s radical youth:

Above all [Du Bois] did not content himself with hurling invenctives for emotional relief and then to retire into smug passive satisfaction. History had taught him it is not enough for people to be angry. The supreme task is to organize and unite people so that their anger becomes a transforming force (Freedomways, Spring 1968).

The ruling class did everything in its power to divert and defeat the new direction taken by King. The capitalist mass media went all out to promote the activity and the ideology of those Black and white radicals for whom King was “too non-violent” and the Communist Party “too conservative.”

While Newton, Cleaver, and Hilliard waved the Little Red Book and talked of picking up the gun, they were joined in these activities by middle-class white radicals who also came forward with “new” interpretations of Marxism. All of this created diversions and confusion on the campuses, in the ghettos and in the peace movement.

[…]

Objective Laws of Development

Those who point to the lumpenproletariat as the revolutionary vanguard disregard the objective laws of historical development. In pre-capitalist societies, poverty and oppression were even greater than under capitalism. But oppression in itself, no matter how great, does not create the basis for the struggle to abolish oppression.

Because of the specific nature of exploitation under capitalism, the working class, which collectively operates the mass production process of the privately owned monopolies, is transformed into the gravedigger of the system. That is why Marx and Engels wrote in The Communist Manifesto: “Of all the classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class.”

No fundamental change–or even a challenge to the monopolists–can occur without the working class. And today the proportion of Black workers in basic industries such as steel, coal, auto, transport and others is transforming the prospects for the class struggle and Black liberation.

These Black workers, who share the oppression of all Black Americans, also share the exploitation experienced by their fellow white workers. But as compared to these white workers, they are forced to suffer from racist superexploitation that makes sure they have the worst jobs, are always the last hired and first fired.

At the same time, history has assigned a doubly significant role to Black workers–as the leaders and backbone of the Black liberation movement, and as a decisive component of the working class leadership of the anti-imperialist struggle as a whole.

It is the monopolists’ fear of Black, white, Brown, Yellow, Red and working class unity, which in turn can form the basis for still broader people’s unity, that is behind racism and anti-Communism, the main ideological weapons of the ruling class.

[…]

Accommodation–or Struggle

Neither Newton’s nor Cleaver’s concept of a “survival program” is in the interests of the people. While Cleaver expresses the ultra-Leftist face of opportunism–“urban guerilla warfare now”–Newton’s opportunism takes a different form.

Describing his “survival program,” Newton says: “We serve [the people’s] needs so they can survive oppression. Then, when they are ready to pick up the gun, serious things will happen” (Black Panther, April, 1971). In other words, Newton would have us believe that accommodation today will lead to revolution tomorrow!

Both the “survival program” Newton-style (“wait until the masses are ready to pick up the gun”) and the “survival program” Cleaver-style (“pick up the gun now”) objectively amounts to the same thing–desertion of people’s struggles.

The cause of liberation cannot be served by a negative idea–“survival” pending a future day when “serious things will happen.” What is needed is a struggle program for the immediate interests of the people and for their ultimate liberation from capitalist, racist oppression.

Marx and Engels taught that the salvation of the exploited requires an ever-expanding unity in struggle even so much as to retard the downward spiral of exploitation and oppression. This concept is even more acutely relevant today. By contrast the idea of a “survival program” evokes passivity…

[…]

The Future Determines Its Own Tactics

To help preserve his “revolutionary” image while introducing his Black capitalist “survival program,” Newton makes use of the “when they are ready to pick up the gun” concept. But, shorn of its rhetoric, this is the equivalent of saying, “Since the masses are not yet ready to pick up the gun, we will table the question of picking up the gun until the masses are ready to put it on the agenda.” This is simply another way of creating passivity… Tomorrow’s tactics cannot be determined today. Future struggles, although they will be influenced by the outcome of today’s, will, depending on the concrete conditions that exist then, determine the tactics that go on tomorrow’s agenda.

Focusing on the gun in the future leads to frustration in the present. It carries the implication that ant method short of the gun is inadequate or futile, amounting to no more than a holding operation until the real thing happens–merely a question of firing blanks until at long last reaching the point of “picking up the gun.”

This same idea is expressed in a slightly different form by other individuals on the Left. According to one such view, “the possibilities of peaceful struggle have not yet been exhausted.” This formulation implies that while armed struggle is not “yet” on the agenda, a revolutionary strategy must be based on the assumption that it will inevitably be placed there.

This view operates on the fatalistic notion that no matter what changes occur in the relationship of forces on a national and world scale, the working class and its allies will inevitably exhaust their capacity to prevent the ruling class from imposing armed struggle on the revolutionary process… Against such erroneous views, Lenin wrote:

Marxism demands an attentive attitude to the mass struggle in progress, which, as the movement develops, as the class consciousness of the masses grows, as economic and political crises become more acute, continually gives rise to more varied forms of defense and attack…

In the second place, Marxism demands an absolutely historical examination of the question of the forms of struggle. To treat this question apart from the concrete historical situation betrays a failure to understand the rudiments of dialectical materialism. At different stages of economic evolution, depending on differences in political, national, cultural, living and other conditions, different forms of struggle come to the fore and become the principal forms of struggle; and in connection with this, the secondary, auxiliary forms of struggle undergo change in turn (V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. XI, pp. 213-214)

Marx, Engels and Lenin fought against ideas that foreclosed the possibility of varying the forms of revolutionary struggle in the transition to socialism. They rejected both the Right opportunist illusion that the transition would inevitably be peaceful, and the “Left” opportunism that proclaimed armed struggle as the only path to socialism for every country.

Today’s Right opportunists also predict that armed struggle will not be necessary, while the “Left” opportunists predict that it will be inevitable. Marxism-Leninism opposes both the will and the won’t of these two faces of opportunism, both of which tend to disarm the mass struggle.

While opposing “Left” concepts of the inevitability of armed struggle, Communist strategy simultaneously opposes Right opportunist illusions that transition to socialism and liberation is possible without the sharpest class struggles combined with the struggles of all the oppressed to curb and defeat the power of racist monopoly.

As Lenin wrote, “To attempt to answer yes or no to the question whether any particular means of struggle should be used, without making a detailed examination of the concrete situation of the given movement at the given stage of its development, means completely to abandon the Marxist position” (Collected Works, Vol. XI, p. 224).

Editors’ note: “The Crisis of the Black Panther Party,” first published in Political Affairs in August 1971, was reprinted in Strategy for a Black Agenda: A Critique of New Theories of Liberation in the United States and Africa (New York: International Publishers, 1973).

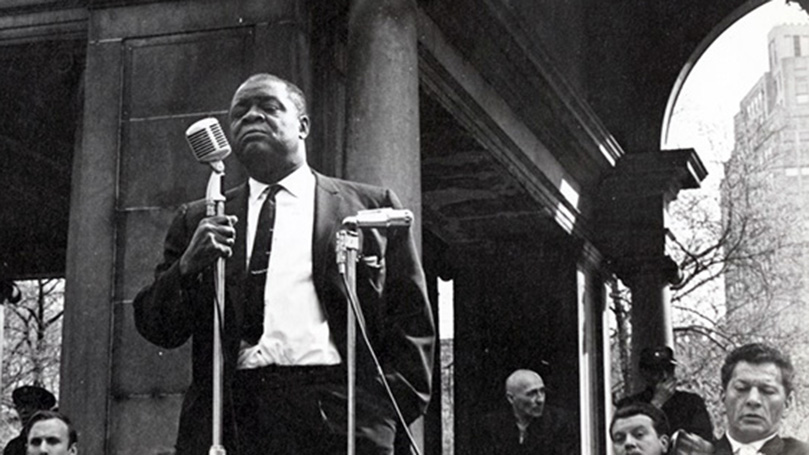

Image: People’s World archives. Henry Winston served as national chair of CPUSA from 1966 until his death in 1986.

Join Now

Join Now