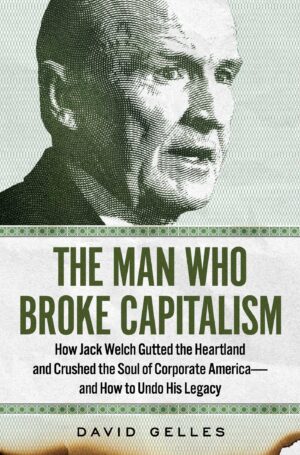

David Gelles, The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America — and How to Undo His Legacy, Simon & Schuster, 2022.

The Man Who Broke Capitalism is the intriguing title of a new book by New York Times business columnist David Gelles. It offers a close study of neoliberal policies from the 1970s onward, as exemplified by one man: Jack Welch, Chairman and CEO of General Electric from 1981 to 2001. During the two decades of his tenure, GE went from a $14 billion manufacturer known as “the epitome of the benevolent postwar employer” to a $600 billion behemoth and the most valuable company in the world. Jack Welch emerges in these pages as a hideous caricature of all that we find reprehensible in capitalism: greed, entitlement, contempt for humanity, toxic masculinity, insidious conspiracy theories, and profits before people. Welch embodied the worst practices of the period: massive layoffs, decline in union density, off-shoring, shareholders-first, and the further entrenchment of finance capital. The individualist focus allows Gelles to tell an intriguing story complete with salacious details, temper tantrums, and profits-gone-wild, but it ultimately hinders both our understanding of the period and Gelles’ ability to predict the future.

The backdrop of Gelles’ premise of the outsize influence of one man is the contrast between what he calls the “Golden Age of Capitalism,” from post–World War II to the “stagflation” of the 1970s, and the period of the 1990s and 2000s that emerged under Welch and others like him. Gelles begins even earlier, describing GE’s first few decades, from its founding by Thomas Edison in 1892 through the 1920s, when GE’s top brass practiced “welfare capitalism,” characterized by generous health benefits, profit sharing, and high wages for employees. At the time, Forbes Magazine called GE “Generous Electric.” In contrast, during two decades of Welch’s leadership, union density was slashed, hundreds of thousands of workers lost their jobs, and at the same time, shareholders and executives grew unfathomably wealthy. Did one man wreak this havoc?

Jack Welch was born in 1935 to a working-class family in Massachusetts. He was the first in his family to get a college degree, followed by a Ph.D. in chemical engineering, and he started working for GE in 1960. Welch soon distinguished himself as a ruthless competitor, driving his employees hard to increase revenues, and by 1968, he was head of the company’s plastics division, the year after “plastics” became the most famous one-word line in modern cinema. In 1977, Welch took over the company’s financial division, GE Capital, and went on to the chairmanship in 1981. By all accounts he mercilessly bullied all who worked with him. Fortune Magazine called him the “Toughest Boss in America” in a 1984 article. “He attacks almost physically with his intellect — criticizing, demeaning, ridiculing, humiliating.” In his first big speech, he told Wall Street that he wanted GE to be in first or second place in any industry it was in. Otherwise, that division of the corporation would get jettisoned. He said he wanted to turn GE into “an opportunistic, aggressive company that looked for growth wherever it could be found,” in Gelles’ words.

Jack Welch was born in 1935 to a working-class family in Massachusetts. He was the first in his family to get a college degree, followed by a Ph.D. in chemical engineering, and he started working for GE in 1960. Welch soon distinguished himself as a ruthless competitor, driving his employees hard to increase revenues, and by 1968, he was head of the company’s plastics division, the year after “plastics” became the most famous one-word line in modern cinema. In 1977, Welch took over the company’s financial division, GE Capital, and went on to the chairmanship in 1981. By all accounts he mercilessly bullied all who worked with him. Fortune Magazine called him the “Toughest Boss in America” in a 1984 article. “He attacks almost physically with his intellect — criticizing, demeaning, ridiculing, humiliating.” In his first big speech, he told Wall Street that he wanted GE to be in first or second place in any industry it was in. Otherwise, that division of the corporation would get jettisoned. He said he wanted to turn GE into “an opportunistic, aggressive company that looked for growth wherever it could be found,” in Gelles’ words.

Gelles centers Welch’s actions in the academic approaches offered in the 1970s by Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, especially the idea that a corporation’s loyalty is to the shareholders alone, not to customers, employees, or the general public. In Friedman’s formulation, government regulations and workers’ rights had to go, and CEOs should be rewarded with shares of stock, to incentivize their quest for profit. Welch took these principles from academia to the real world, Gelles argues, and grew GE into a behemoth using three tools: downsizing, deal making, and financialization.

Once unleashed on the world as CEO of GE in 1981, Welch began ruthlessly firing workers and shutting down factories. The media gave him the nickname “Neutron Jack,” a reference to the neutron bomb, a horrific weapon designed to kill all life in an area while leaving the structures intact and ready for occupation. Welch instituted a system of constant layoffs that came to be known as “rank and yank”; every year, managers of each department had to rank their employees into three groups, the top 20%, the middle 70%, and the lowest 10%. Then, the bottom 10% were fired. Some work was outsourced to contractors that paid lower wages with fewer benefits, and some work was moved off-shore. Welch was famous for saying that the ideal factory would be built on a barge that could be moved to wherever labor was cheapest and profits most accessible.

The way that Welch expanded GE while cutting its workforce was through acquisitions. One employee called it the “Pac-Man model. Just eat up companies. Acquire growth.” Under relaxed corporate regulations during the Reagan administration, Welch managed the acquisition of RCA in 1985, selling off some of its parts until its workforce was cut by 60%. Over the years, he would acquire hundreds of companies, selling off the parts that didn’t interest him and downsizing the workforce that was left.

The way that Welch expanded GE while cutting its workforce was through acquisitions. One employee called it the “Pac-Man model. Just eat up companies. Acquire growth.” Under relaxed corporate regulations during the Reagan administration, Welch managed the acquisition of RCA in 1985, selling off some of its parts until its workforce was cut by 60%. Over the years, he would acquire hundreds of companies, selling off the parts that didn’t interest him and downsizing the workforce that was left.

Welch acquired the investment bank Kidder Peabody for GE Capital in 1986. Gelles says that this move “push[ed] GE deeper into finance, where, [Welch] believed, you could conjure profits from thin air — without the burden of messy factories, or unionized workers.” In 1977 when Welch took over the division, GE Capital loaned relatively small sums to customers who may have been buying their first big appliances; the division had about $11 billion in assets. After Welch’s tenure as CEO, its assets had grown to $370 billion, and it had operations in 50 countries. Welch used questionable and opaque GE Capital deals to make sure the company met — on paper — Wall Street expectations every quarter, ensuring that the stock price went up and enriching shareholders including Welch and other top executives. Shady accounting practices also enabled GE to pay lower taxes. Welch used new Reagan-administration relaxed rules to spent $10 billion in stock buybacks, again enriching shareholders by driving up the price of each share. Buybacks became a trend that Gelles estimates has stunted all workers’ salaries, not just GE’s, despite increased worker productivity. The increased value that workers produced in this period went directly to the penthouses and private airplanes of CEOs and investors.

Gelles argues that these practices led inexorably to GE’s star falling precipitously in the Great Recession and the ultimate dismantling of GE Capital. The division’s pension fund faced a $31 billion shortfall, throwing the retirement of 600,000 former employees into doubt. The SEC had caught on to the shady practices of the past and fined the company $200 million in 2018, when GE was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, a form of ruling-class cancellation. In 2019, GE settled with the Department of Justice over its role in the subprime mortgage crisis and paid a fine of $1.5 billion. Although the practices that Welch instituted ended up costing GE dearly, he received a retirement package that included an apartment in Trump International Hotel & Tower, complete with housekeepers, laundry services, and fresh flowers; country club memberships; helicopter and limousine services; communications devices; and box seats at the opera and court-side seats at Madison Square Garden. These perks were in addition to his pension of almost $8 million annually.

Gelles recounts some stories of Welch’s protégés, making the argument that Welch and those he influenced ended up similarly damaging their companies by refusing to invest in wages, workforce development, research, or innovation. One compelling story is about Welch protégé Jim McNerney’s tenure as Boeing CEO, when he ultimately set into motion the chain of mistakes that led to two major plane crashes in 2018–19. Although most of these executives left companies worse off than they were when they took control, in each case, they left with a generous “golden parachute.”

Gelles recounts some stories of Welch’s protégés, making the argument that Welch and those he influenced ended up similarly damaging their companies by refusing to invest in wages, workforce development, research, or innovation. One compelling story is about Welch protégé Jim McNerney’s tenure as Boeing CEO, when he ultimately set into motion the chain of mistakes that led to two major plane crashes in 2018–19. Although most of these executives left companies worse off than they were when they took control, in each case, they left with a generous “golden parachute.”

Welch continued to be despicable after retirement. He launched the Jack Welch Management Institute, a for-profit online business administration master’s program which he advertised in an appearance on his pal Donald Trump’s show The Apprentice. In October 2012, just before Obama’s reelection, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly jobs report showed that the unemployment rate had dropped below 8% for the first time since the recession. Welch posted on Twitter, “Unbelievable jobs numbers,” and suggested that BLS employees had fudged the numbers in order to help Obama be reelected. The baseless claim was quickly refuted, including by Fortune Magazine, but Fox News hosts jumped on the lie and perpetuated it, launching a movement known as “jobs report truthers.” Welch noticed the attention he was getting and doubled down on the lie at paid talks . . . does all this sound familiar? He wasn’t the first — Trump had launched birtherism a year earlier — but Gelles points out that “Welch was at the vanguard of a disinformation revolution.”

In his penultimate chapter, Gelles show the continuity between practices Welch pioneered and contemporary capitalism, arguing that Jeff Bezos is the new Jack Welch. He laments the continued effects of rampant mergers and acquisitions, the shift to the gig economy, and the suppressed minimum wage. In the 1980s, Gelles reports, less than half of corporate profits went to shareholders. Now the figure is 93%. CEO pay is now 320 times what the corporation’s average worker earns. Gelles reminds us who caused contemporary problems: “It was executives, not congressmen, who closed factories in Ohio.”

Gelles’ final chapter, “Beyond Welchism,” describes a kinder, gentler capitalism in companies like Unilever and PayPal, which embrace stakeholder rather than shareholder capitalism. He outlines policies that he says will address some of the wrongs wrought by Welch and his ilk, for example, stronger anti-trust policies, caps on executive compensation, and a higher minimum wage.

My first and main criticism of David Gelles’ argument comes clearly into focus in this last chapter. Gelles sees Jack Welch as having an outsize influence on business practices and structures. In contrast, the way we look at the dynamics of change in the political economy, it is structures that shape people’s ideas and behaviors. Just as we must resist the “Great Man” theory of history, so must we avoid the “Evil Man” theory. If one depends too much on the explanatory power of one individual’s impact, one can also overestimate the reversibility of the trends, which Gelles does in the final chapter when he considers the question raised by the last part of his subtitle: how to undo Welch’s legacy. Gelles ends up overly optimistic about the future because he has found a handful of individuals who might be influential in the future. He suggests that “big business is now beginning to tackle climate change,” CEOs are becoming more “enlightened,” and some represent “a new generation of corporate leaders rewriting the rules” and espousing “stakeholder capitalism.”

My first and main criticism of David Gelles’ argument comes clearly into focus in this last chapter. Gelles sees Jack Welch as having an outsize influence on business practices and structures. In contrast, the way we look at the dynamics of change in the political economy, it is structures that shape people’s ideas and behaviors. Just as we must resist the “Great Man” theory of history, so must we avoid the “Evil Man” theory. If one depends too much on the explanatory power of one individual’s impact, one can also overestimate the reversibility of the trends, which Gelles does in the final chapter when he considers the question raised by the last part of his subtitle: how to undo Welch’s legacy. Gelles ends up overly optimistic about the future because he has found a handful of individuals who might be influential in the future. He suggests that “big business is now beginning to tackle climate change,” CEOs are becoming more “enlightened,” and some represent “a new generation of corporate leaders rewriting the rules” and espousing “stakeholder capitalism.”

A political theorist made this analogy early in the twentieth century. Imagine a stadium full of people. It starts to rain, and one person in the crowd is the first to raise his umbrella. In a few minutes, many people have unfurled umbrellas. Do they do this because they accept the leadership of that first damp person in the crowd? No, many people are acting in similar ways because they find themselves responding to the same conditions surrounding them. Capitalism doesn’t need a man to break it; it’s fully capable of breaking itself by developing contradictions that can’t hold and careening toward the next inevitable economic crisis.

Looking backward at Welch and his connections does make it seem like he had a strong influence, but somebody had to be the one to check off more of the characteristics of contemporary capitalism than others. Individualizing history may make for a fascinating and infuriating narrative, tracing as Gelles does the shenanigans of Welch and Welch wannabes running roughshod over the working class. But it doesn’t give an accurate representation of the causes that capitalism has taken the turns it has in the last half century.

A second criticism is of the construct of the “Golden Age of Capitalism.” Here it is portrayed in idyllic terms, and conditions for some workers in the post-war period were doubtless better than workers enjoy today. But this golden world was built on the super-exploitation of nationally oppressed minorities and the unpaid labor of millions of women burdened with child-rearing responsibilities. The seeds of “Welchism” were planted in those years, and the ruling class was hard at work setting up conditions that would make exploitation of the working class more profitable than ever for themselves.

However different from my own perspective Gelles’ individualist approach to economic history is, I was happy to have read this book. It’s a good review of the last forty years of political economy, which might be especially useful for young people who weren’t there to experience each blow against progress firsthand. It’s a readable, well-organized, and concise book, with a comprehensive index and documentations of sources. Gelles has given us a handy compendium of every despicable thing about contemporary capitalism, and I for one will keep it on my bookshelf for future reference.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: General Electric sign, Chuck Miller (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); “Plastics,” The Graduate, screenshot (YouTube); Corporate handshake, Wirawat Lian-udom (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Jack Welch as a Muppet (CC BY 2.0).

Join Now

Join Now