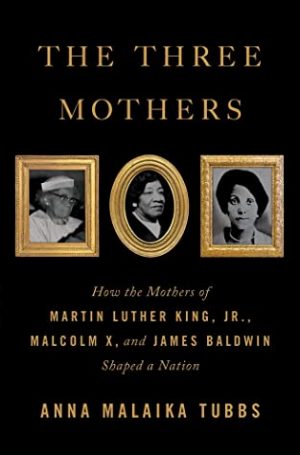

The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation, Anna Malaika Tubbs, New York: Flatiron Books, 2021.

“All our achievements are Mom’s”

—Malcolm X, The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Anna Malaika Tubbs has written about Alberta King, Louise Little, and Berdis Baldwin to honor Black motherhood and to defy historical “erasure” (214). She proclaims that “Black women exist — and exist positively” (5).

The lives of these three women may seem less than remarkable, but Tubbs, herself a Black mother, reminds readers that Black motherhood is, in itself, courageous — a form of subversion in response to American racism:

Those of us who nurture the lives of those children who are not supposed to exist, who are not supposed to grow up, who are revolutionary in their very beings are doing some of the most subversive work in the world. (175)

Famed historian Howard Zinn dared to look at U.S. history from the viewpoint of its victims and confirmed Tubbs’s perspective: “There is not a country in world history in which racism has been more important, for so long a time, as the United States” (Zinn, 23). Zinn elaborated, “Two elements made American slavery the most cruel form of slavery in the world: the frenzy for limitless profit that comes from capitalist agriculture; and the reduction of the slave to less than human status by the use of racial hatred” (28). And the great Malcolm X beautifully summed it up:

Indeed, how can white society atone for enslaving, for raping, for unmanning, for otherwise brutalizing millions of human beings, for centuries? What atonement would the God of Justice demand for the robbery of the black people’s labor, their lives, their true identities, their culture, their history—and even their human dignity?” (Malcolm X, Autobiography, 376)

Enslaved Black mothers were reduced to “givers of property” (176). Fannie Lou Hamer reminds us that only Black people had babies sold away from mothers and mothers sold from babies (176). During slavery a Black baby was a mere commodity and Black mothers simply “vessels through which new property would arrive” (86). But after abolition it was no longer profitable to whites for Black people to procreate, and a fear developed that Blacks would one day outnumber whites. Thus began practices of forced sterilization and “ugly eugenicist” efforts (94).

The Three Mothers outlines the various racist depictions of Black women, men, and children in American culture. Black men have been portrayed as “scoundrels intent on brutalizing white women,” (56) while Black women have been depicted at various times as mammies, welfare queens, jezebels, and matriarchs. The mammy caricature was “loyal, plump, and ignorant of her own needs” (57) as she served whites. The matriarch stereotype, rather than praising Black women for independence and self-reliance, accused the “matriarchal structure of Black households” for the emasculation of Black husbands and fathers. Marx taught that material production defines mental or cultural production. And so we see capitalism and slavery as means of production leading to cultural representations of Black children as “pickaninnies” with dark black skin, bulging eyes, and unkempt hair — images that dehumanized Black children as worthless and Black parents as inept (54).

Despite these conditions and stereotypes, as Tubbs asserts, throughout U.S. history African Americans have practiced “revolutionary love” (80) by daring to teach their Black children to love themselves, for “if they cannot love and resist at the same time, they will probably not survive” (81).

Tubbs addresses the racism, sexual oppression, and class oppression that Black mothers have faced. She speaks of the hostile “circumstances” of racist and capitalist society in which Black mothers are “deemed less than but forced to be more than” (219). She acknowledges the powerful historical events during the times of the three mothers and their sons: two World Wars, the Great depression, the Harlem Renaissance, the great migration northward from 1915 to 1960, and mass incarceration.

American women achieved the right to vote in 1920, but Black women were denied participation in the suffrage movement as white women leaders curried favor with powerful white men. There was debate regarding whether Black men, denied dignity and rights in America, should fight abroad in capitalist wars. Tubbs explains that about 350,000 Black men fought in World War I and 2.5 million in the Second World War. But Marcus Garvey, for example, urged African American men to decline enlistment during WWI.

In 1919 returning Black veterans of WWI were rewarded for their service with such racist violence that it has gone down in history as the “Red Summer” (81). The link between economics and racism is revealed by the fact that so much of that violence was rooted in white fear of job loss to returning Black veterans. It was Malcolm X, in his autobiography, who really made the point regarding hostile economic and social forces shaping Black lives. He wrote about his old bookmaking friend and gambling hustler West Indian Archie. He was slowly dying of syphilis when Malcolm paid him a visit in his cheap hotel room and told him that, in a different society, he might have been a scientist or mathematician. “Red, that sure is something to think about,” was West Indian Archie’s reply (Malcolm X, Autobiography, 219).

Anna Malaika Tubbs rightly makes the point again and again that the very act of giving birth to a Black child in racist, capitalist America is an act of courage. She honors Alberta, Berdis, and Louise by asserting that their three sons, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin, respectively, were simply “following their mothers’ leads” (8) and accepting, as Marx taught, that “the law of life is struggle” (Wheen, 383). But these three women and their famous sons saw more than their share: each woman “was alive to bury her son” (8).

Berdis Baldwin was a widowed single mother of nine at age 41. Alberta King, a member of the NAACP and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, was gunned down in the renowned Ebenezer Baptist Church in 1974. Louise Little, who spoke five languages (44), discovered the teachings of pan-Africanist and separatist Marcus Garvey and wrote for the Garvey paper Negro World. After her husband was murdered for being an “uppity nigger” (76), Louise was so stressed by hardship as a single mother that she was set upon by welfare workers and bill collectors. In 1939 she was diagnosed with paranoia and maladjustment, declared insane, and confined against her will to a state hospital for 27 years. Malcolm was in 7th grade at the time. Her children were placed in separate foster homes. It is worthy to note that, to this day, the American mental health industry conforms to a medical philosophy which locates psychopathology within the individual. Context and environmental factors such as racism and economic injustice which create human distress are noted as mere afterthoughts.

Berdis Baldwin was a widowed single mother of nine at age 41. Alberta King, a member of the NAACP and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, was gunned down in the renowned Ebenezer Baptist Church in 1974. Louise Little, who spoke five languages (44), discovered the teachings of pan-Africanist and separatist Marcus Garvey and wrote for the Garvey paper Negro World. After her husband was murdered for being an “uppity nigger” (76), Louise was so stressed by hardship as a single mother that she was set upon by welfare workers and bill collectors. In 1939 she was diagnosed with paranoia and maladjustment, declared insane, and confined against her will to a state hospital for 27 years. Malcolm was in 7th grade at the time. Her children were placed in separate foster homes. It is worthy to note that, to this day, the American mental health industry conforms to a medical philosophy which locates psychopathology within the individual. Context and environmental factors such as racism and economic injustice which create human distress are noted as mere afterthoughts.

Anna Malaika Tubbs honors Black mothers and speaks to their needs. She calls for societal protection from domestic violence and gun violence. She urges reforms in health care, mental health care, childcare, and prison policy. She cites the need for a universal income and reproductive justice. How do we achieve these goals? Henry David Thoreau observed, “There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root” (Catusco, 6). The failure of The Three Mothers is that Tubbs is hacking at branches. She does not strike at the root of her people’s misery: capitalism. She fails to identify socialism as the only salvation for Black mothers and their children. She comes close, by decrying “a society that defines good as profit rather than human need and capital as more important than humanity” (11). But as Malcolm X said, “Make it plain” (Autobiography, 173). By not clearly embracing socialism, Tubbs is hoping that capitalism, the very system so devoted to profit that it treated her people as livestock, will be reformed.

Whether the issue is economic injustice, racism, police brutality, or mass incarceration as a continuation of slavery, capitalism is the problem. It cannot be the solution.

Sources

John-Paul Catusco, “America’s Museum of Exploitation,” The People 110, no. 5, 2000.

Malcolm X, with Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Grove Press, 1964.

Malcom X, The Final Speeches, edited by Steve Clark, Pathfinder Press, 1992.

Francis Wheen, Karl Marx: A Life, W.W. Norton, 2000.

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, Harper Perennial, 1980.

- Tags:

- Book Reviews

Join Now

Join Now