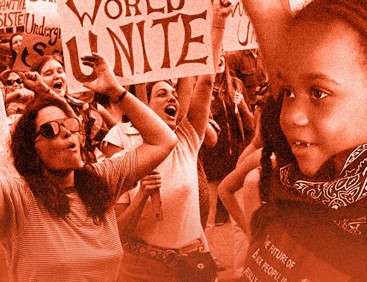

The call for unity resonates across a wide swath of today’s democratic and social movements. Attend any demonstration and you’re likely to hear marchers rhythmically shouting in Spanish and English “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido” (The people united will never be defeated), a chant born and made famous around the world by Salvador Allende’s fight for popular unity in Chile.

In the U.S. today the country faces a growing fascist menace not unlike what the Chilean people faced during the Pinochet dictatorship. The challenge is to go beyond slogans and find a strategy that will build the unity needed: that strategy is creating from the ground up a broad anti-fascist alliance. Fortunately, there’s a lot to build on.

Indeed, unity concepts and slogans abound in U.S. history and culture. One of its first expressions came from Abraham Lincoln, who, in an 1858 convention speech on the eve of the Civil War, warned that slavery threatened to tear the nation asunder. “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” the then GOP candidate for the U.S. Senate famously declared, arguing that the country could not survive, half slave and half free.

“An injury to one is an injury to all” is another popular slogan that came straight out of the labor movement at the dawn of the last century. The IWW’s Big Bill Haywood attributed the saying to David C. Coates, a socialist labor leader and former lieutenant governor of Colorado.

A few decades later, “black and white, unite and fight” was the clarion call of communist organizers in the CIO as they led the fight to organize workers in the steel, auto, and electric industries in the 1930s. Today, “black, brown, Asian, and white, unite and fight” more accurately reflects the increasingly diverse composition of the U.S. working class.

Fighting for unity, while not always successful, is a veritable way of life for U.S. communists, and many of the Party’s strategic concepts revolve around it. Left-center unity, that is, the imperative of developing strong ties between left and moderate forces in the trade union movement, has long been a mainstay of CPUSA’s labor policy and remains so today.

An all-people’s unity strategy (which basically means unity of the entire people) was advanced by the Hall-Winston leadership in the 1980s, after the Republican National Committee (RNC), at the behest of the Chamber of Commerce and the big banks, shifted far to the right.

In light of the country’s deepening political crisis, this strategy retains all of its potential force. In fact, Trump’s threat to run for a second term makes it even more relevant. All-people’s unity is the current application of what the communist movement once called the “popular front” strategy, that is, the creation of a broad coalition of the American people to oppose the MAGA movement and the threat of a fascist dictatorship. In its day-to-day work, particularly at the local level, the CPUSA strives to put a working-class stamp on this front by centering its election activity where possible with trade unions, community groups, and other movements who operate independent of official Democratic Party campaigns. Taking initiative on the key issues is vital, including fighting for the passage of abortion rights, the PRO-ACT, voting rights, climate change, and other legislation.

Of course, it’s one thing to call for unity and quite another to achieve it. Alliance building can be halting and at times even tortuous. Differing agendas, egos, and experiences can impact the ability to forge viable coalitions. The multi-racial, multi-gendered, and cross-generational diversity of the U.S. working class often requires taking special measures to respond to the challenges faced by different sections of the class.

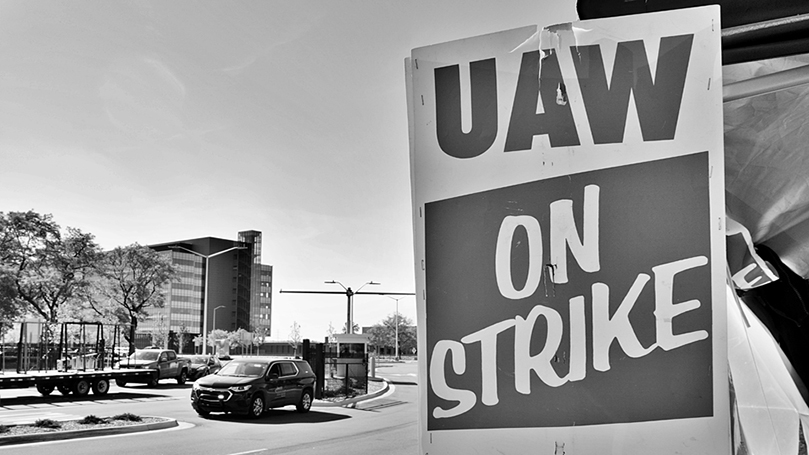

Building unity between the trade union movement and the young generation (what the CP terms labor/youth unity) illustrates this need. For example, during the auto workers strike in 2019, the industry’s two-tier wage system — where new young hires are paid substantially less than older workers — was a major sticking point. And while progress was made to reduce the wage differential during negotiations, it was not done away with. The recent UAW convention pledged to take up the issue in a major way in future contract talks. One resolution, according to People’s World, instructed the union’s executive board to “reject management proposals which seek to divide the membership through tiered wages, benefits or post-employment income and benefits.” Thus, unity between older and younger workers required confronting the company’s tactic of dividing by pay scale. In other words, a united front on the picket line meant the union had to address younger workers’ special demands for equal pay – a refusal to do so could have meant the defeat of the strike.

Another key issue is fully appreciating the nature and strength of one’s class opponents. Speaking to this challenge, Henry Winston, the Party’s late national chairman, once placed the issue this way when addressing building labor community coalitions in response to the collapse of the steel industry: “Why is such unity necessary?” he asked. “Because victory in the battle against monopoly is impossible without it — the ruling class in this country is too strong.” The working class, the CP chairman argued, cannot win this fight alone.

In a similar vein, African American, Latino, women’s, and LGBTQ movements can ill afford go-it-alone approaches. And while Winston stressed that confronting the most powerful ruling class in history required focusing on common demands, he also hastened to place in the foreground special compensatory measures like affirmative action as necessary for binding alliances with those experiencing historic discrimination, a point that some continue to dismiss as concessions to “identity politics.”

The working class learned the lesson of building unity of action the hard way. Strikes were lost, campaigns for elected office defeated, attempts at social revolution vanquished at almost incalculable costs. Recall that the Paris Commune was drowned in the blood of 35,000 communards, after 30 days of wielding power.

Set back after these terrible events, but undaunted, burgeoning movements had to consider things afresh, discard strategies that proved infeasible, tinker with others that showed greater promise, and adopt whole new methods as conditions changed. As the bourgeois democratic revolutions against monarchies gained momentum in the 19th century in countries like Germany, France, and England, narrow approaches had to be rejected. New avenues for struggle had to be sought based on the institutions that began to emerge as people began to organize themselves according to faith, occupation, and interest.

The notion, for example, that small, highly committed groups could successfully contend for political power was frontally challenged by Frederick Engels: “The time is past for revolutions carried through by small minorities at the head of unconscious masses,” he wrote in his 1895 introduction to Marx’s “Civil War in France.” Engels continued, “When it gets to be a matter of the complete transformation of the social organization, the masses themselves must participate, must understand what is at stake and why they are to act.”

The struggle for democracy in combination with the class struggle began to take center stage. Socialist parties now had to take into account building alliances as the franchise became a major factor in the exercise of political power. In several countries, Marxist parties were able to build mass electoral coalitions and win office.

Had new, peaceful paths to power been discovered? At first blush it appeared so, and even Engels, the veteran of many a class battle, seemed quite taken with the social democratic movement’s late 19th-century electoral successes. Still, the old revolutionary took pains to point out that these victories in no way meant renouncing the goal of revolution. Engels warned: “Of course, our comrades abroad have not abandoned the right to revolution. The right to revolution is, in the last analysis, the only real ‘historic right’ upon which all modern states rest without exception.”

Had new, peaceful paths to power been discovered? At first blush it appeared so, and even Engels, the veteran of many a class battle, seemed quite taken with the social democratic movement’s late 19th-century electoral successes. Still, the old revolutionary took pains to point out that these victories in no way meant renouncing the goal of revolution. Engels warned: “Of course, our comrades abroad have not abandoned the right to revolution. The right to revolution is, in the last analysis, the only real ‘historic right’ upon which all modern states rest without exception.”

Some, however, appeared not to have listened to Marx’s old friend’s advice. Even Marx’s sage instruction when critiquing the Germany Social Democratic Party’s Gotha Program was ignored. Marx had urged comrades to enter into compromises necessary to achieve practical aims but to never make theoretical concessions.

Instead, theoretical concessions were made by those adopting Eduard Bernstein’s “the movement is everything, the goal, nothing” “update” of Marx. Under Bernstein’s advocacy, reforms became the be-all and end-all of everything: reforms would gradually evolve themselves into socialism. The goal of working-class power was lost.

What went wrong? Varying explanations have been offered: the buying off a section of the trade union leadership and the emergence of a “labor aristocracy,” an undue domination of the labor movement by middle-class elements; the offering of a psychological “wage” to white workers to promote a feeling of racial superiority, was an explanation posited by W. E. B. Du Bois in Black Reconstruction.

Or could the problem lie in another direction, perhaps in the coalition strategy itself? It’s a matter of historical record that radical reforms advocated by the socialist parties got watered down as their electoral successes increased. The closer some came to power, the greater was the temptation to concede this or that plank of their program in order to win sections of the vote.

At the turn of the 20th century, echoes of these debates entered the Russian Social Democratic movement, albeit in quite different circumstances. Russia remained largely trapped in feudal-like conditions and was still ruled by a hereditary monarchy. The socialist movement had to find a path to defeat the czar and also design tactics that would address the growing capitalist class in a huge country with an extremely diverse population and a political culture steeped in backwardness. Who could the workers unite with? Whither lay the promised land, and with whom could the oppressed masses get there?

In these circumstances a fierce argument broke out. All the Marxists agreed the country needed to pass through capitalism — at least in some form — but there were sharp differences about what that entailed. A revolution was required to get rid of czarism — on this there was consensus. What kind of alliances were needed and which class forces would lead them was another matter entirely. A section of the party favored confining the coalition to the working class and peasants alone. Others supported including capitalists in the mix. The former group were called Mensheviks. They opposed allying with Russia’s nascent merchants and industrialists for fear of being dissolved in a growing sea of bourgeois democracy.

The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, conversely, favored including the capitalists. The issue in the Bolshevik leader’s view wasn’t whether to support a cross-class alliance — the challenge was how to do it. In Lenin’s view, the point was to fight for working-class leadership of this alliance, to place a proletarian “stamp” on the democratic revolution. Doing so would preserve the working class’s independent role and reduce the risk of its objectives being subsumed. How? By fighting for consistent democracy, in other words, by carrying to completion the democratic fight for voting, representative government (a constituent assembly), land reform, the eight-hour day, and a government capable of inflicting a “decisive defeat of reaction.” In this manner, Lenin argued, the working class would stand the best chance of positioning itself within the emerging capitalist order.

These arguments are pointedly made in Lenin’s Two Tactics, where, in embryonic form, and yet unnamed, what became known as the united front concept is first introduced. They guided Bolshevik domestic policy through 1917.

The “united front tactic” was formally adopted by the world movement at the 4th Congress of the Communist International in 1922. What is the united front? Simply put, it is a politically diverse coalition of working people who come together to address a specific set of issues. Ideological differences, for the moment, are set aside in pursuit of common goals.

What goals? In the first place, to resolve the bread-and-butter issues confronting the working class at any given point in time. In a 1922 speech, Grigory Zinoviev, one of the leaders of the Comintern, put it this way: “We are in such a phase of the struggle of the world proletariat that we should unite in the struggle for the eight-hour day, aid for the unemployed, and in the fight against the offensive of capital.”

The adoption of the united front was a major part of Lenin’s polemic against “left-wing” communism, the knee-jerk responses of the newly formed parties that had split from the 2nd International, many of whom rejected electoral work, shunned compromises, and, heady with the success of the October Revolution, believed themselves to be on the verge of world revolution. Under the influence of strategies like Béla Kun’s “theory of offensive” and Leon Trotsky’s “permanent revolution,” failed attempts at state power occurred in Hungary, Germany, and other countries with disastrous results.

A protracted era of class and democratic battles instead were at hand.

Lenin, on the other hand, well understood that, after the initial success of October 1917, the revolutionary moment had passed and with it the chance for a European continent-wide social revolution. A protracted era of class and democratic battles instead were at hand, requiring long and patient preparatory work. In these circumstances he offered the parties of the Third International a three-fold plan: Adopt the united front strategy and tailor it to fit each country; win over the majority of the working class in the process; and build mass communist parties, all necessary if the socialist revolution would have any real chance for success.

After the Soviet leader’s untimely death, however, and in the face of stiff resistance from potential social democratic allies (the main objects of the united front efforts), the Comintern moved sharply in the opposite direction as the movement’s stubborn affair with leftism returned with a vengeance. Confronted with attacks on communist insurgents by social democratic governments, the parties of the 2nd International were labeled “social fascists,” and with this branding hopes for a united working-class front ended as fascist regimes won power first in Italy, then Germany and other countries.

It was in these circumstances that the 7th World Congress of the Communist International took place in 1935. The meeting’s main report was delivered by Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian communist, who a few years earlier had been accused of setting fire to the German Parliament, a Nazi provocation designed as an excuse for seizing power. In his famous “United Front against Fascism” speech, Dimitrov reversed course and reembraced Lenin’s united front strategy.

Describing fascism as “the open terroristic dictatorship of the most reactionary sections of finance capital,” Dimitrov offered an olive branch to the 3rd International’s erstwhile Social Democratic allies: Communists, he said, place “no conditions for unity of action except one . . . that the unity of action be directed against fascism, against the offensive of capital, against the threat of war, against the class enemy. This is our condition.”

Precisely what would this unity consist of? “The defense of the immediate economic and political interests of the working class,” argued the general-secretary of the Comintern. Dimitrov suggested a threefold approach: fighting to shift the burden of the crisis onto the rich, resisting all attempts to restrict democratic rights, and combating the war danger.

It is important to point out here that the offer for united action was largely, but not exclusively, aimed at the social democratic parties and trade unions in Europe, as they represented working-class majorities in several countries. The absence of a large social democratic movement in the United States, however, required an adaptation of the tactic to fit American conditions. The U.S. working class was and remains ideologically diverse, harbored in unions, churches, synagogues, and campuses along with various associations and groups, to say nothing of the two main capitalist political parties. What was required on U.S. soil was not a united front of the left but a coalition of the class as a whole. This remains true today.

A brilliant application of this strategy to U.S. conditions in the 1930s was the American Youth Congress (AYC). Initiated by the Young Communist League and its principal organizers, Henry Winston and Gil Green, the AYC included the YWCA, the YMCA, the national students’ union along with scores of union, religious, community, civil rights, and youth groups. It met yearly and at its height boasted over 500 organizations. The AYC promoted a youth bill of rights and succeeded in presenting legislation calling for its enactment in Congress. Eleanor Roosevelt lent it important support.

With the creation of the AYC the Communist Party recognized the need for an even broader response as the fascist threat grew in the U.S. The working class needed allies, a militant multi-class coalition of youth, a “popular” front of the young generation as a whole that could be mobilized in the righteous battles of the times.

The popular front became a material force helping set the course of the entire nation.

And righteous battles they were. Coming out of the Great Depression, the Communist Party and YCL plunged headfirst into organizing the mass production industries, the fight to save the lives of the Scottsboro defendants, and the effort to break the back of segregation. These were the circumstances out of which Lenin’s idea of a working class-led, cross-class coalition, though born of different conditions, in a faraway land, took root and blossomed. Indeed, the popular front proved more than a notion: it had been given life and organizational form, and it became a material force helping set the course of the entire nation.

Dimitrov’s report described the popular front this way:

The formation of a wide anti-fascist People’s Front . . . is closely bound up with the establishment of a fighting alliance between the proletariat, on the one hand, and the laboring peasantry and basic mass of the urban petty bourgeoisie who together form the majority of the population even in industrially developed countries.

With World War II engulfing much of the planet and the USSR bearing the brunt of the battle, this grand coalition grew to include not only sections of the capitalist class but also entire countries — in fact whole groups of countries as the Allies engaged the Axis powers in this gigantic civilizational battle.

Were there grave dangers of getting dissolved in the sea of bourgeois democracy associated with this enterprise? Of course there were: the dissolution of the Communist Party and YCL as World War II drew to a close is a case in point. What began as novel approaches to united front mass work initiated under Earl Browder grew one-sided and detached, drifting far to the right.

Under Browder’s influence, the antifascist wartime emphasis on national interests tended to replace class interests. Class cooperation, in order to defeat fascism, always a slippery slope, morphed into class collaboration. Illusions began to set in, one of the consequences of which was that the domestic expression of Browder’s dream of a new era of post-war cooperation saw no need for a party of militant class struggle. The Party was dissolved and an “association” working within the Democratic Party was created in its stead. The YCL was replaced by an advocacy group and renamed the American Youth for Democracy. Tragically, Browder’s daydream of class peace fell victim to the American nightmare of McCarthyism after Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech in Fulton, Missouri, in 1946. Censorship, jail, mass firings, and war both hot and cold were the high price paid.

With the end of the war, the emergence of a socialist community of nations and the defeat of colonial rule in Africa and Asia, the need for a people’s front internationally began to fade. Events back home, however, were another story. McCarthyism was unleashed in full force. Smith Act– and McCarran Act–driven prosecutions intensified, aided by the Truman administration and GOP majorities in Congress. Backed against a wall and incorrectly seeing fascism on the immediate horizon, the Party leadership fled underground, increasing its isolation from domestic currents and limiting its ability to fight back.

In time, the Cold War began to thaw, at least domestically after the growth of the Civil Rights and free speech movements in the late 1950s. Upon the release of its leadership from prison, party activity resumed. By then an updated strategic and tactical framework was required as Communist activists undertook the long and difficult task of rebuilding relations in workplaces, communities, and campuses. The policy of left center unity by means of building of rank-and-file caucuses helped free the labor movement from the grip of pro-employer, “business union” leaders who embraced anti-working-class policies that were pro-war, anti-affirmative action, anti-immigrant, and anti-international solidarity. Importantly, the Party resumed fielding candidates for local, state, and national office, in an effort to increase visibility and influence the national debate. United front work began in earnest as the Civil Rights revolution unfolded along with the movement to end the Vietnam War. Solidarity with African liberation, particularly South Africa, became a major site of struggle.

In time, the Cold War began to thaw, at least domestically after the growth of the Civil Rights and free speech movements in the late 1950s. Upon the release of its leadership from prison, party activity resumed. By then an updated strategic and tactical framework was required as Communist activists undertook the long and difficult task of rebuilding relations in workplaces, communities, and campuses. The policy of left center unity by means of building of rank-and-file caucuses helped free the labor movement from the grip of pro-employer, “business union” leaders who embraced anti-working-class policies that were pro-war, anti-affirmative action, anti-immigrant, and anti-international solidarity. Importantly, the Party resumed fielding candidates for local, state, and national office, in an effort to increase visibility and influence the national debate. United front work began in earnest as the Civil Rights revolution unfolded along with the movement to end the Vietnam War. Solidarity with African liberation, particularly South Africa, became a major site of struggle.

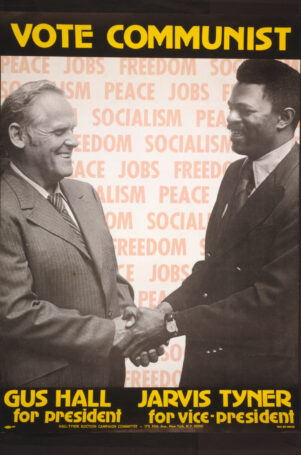

In the mid-1980s a major rightward swing by Big Business took place. The decades-long impact of Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy, the Iran/Contra scandal during Ronald Reagan’s tenure, and the RNC’s Moral Majority venture combined to produce a new and dangerous quality, “a whiff of fascism,” as Gus Hall termed it. At stake was how to tactically adjust, and the question sparked a major debate in the CPUSA leadership.

Vic Perlo, then the party’s leading economist, had been warning of these trends in National Board discussions. Over time, Gus Hall not only became convinced but alarmed and argued that the right danger had become so grave it was necessary to “elect all Democrats and defeat all Republicans.”

A shift in gears was proposed: the party would temporarily suspend fielding candidates for office. Thus began the conversation that would later lead to the CP’s call for the creation of an “all-people’s” front.

Hall was nearly alone in the ensuing debate that ranged from mild questioning, to hemming and hawing, to outright opposition. After a long discussion, the proposal was tabled. In his summary of the first NB debate, the longtime chairman complained, “You comrades don’t realize what you’re up against because you’ve never been hit.” His proposal, however, won the day at a subsequent meeting.

Hall, of course, was himself no stranger to the need for unity. In the days following Nixon’s resignation he called for “people’s unity” to turn the country around. Nixon’s leaving office could result in “a new beginning if it results in a new unity — a unity of all democratic forces, a unity of all working-class forces, a unity of the racially oppressed, a unity of peace forces, and a unity of the younger generation.”

That united new beginning, however, has been long in coming. Soon after the aforementioned debate, the CP National Committee adopted an “all-people’s front” strategy, a policy that, notwithstanding problems of implementation, has stood it in good stead. The election of an extreme right GOP majority in the 1994 midterm elections, led by Newt Gingrich, followed by the two Bush presidencies, the emergence of the Tea Party, and now the growth of a fascist mass movement led by Donald Trump, underscored the party’s farsightedness.

During these years, the CP declined to field presidential candidates, but continued to run for office in much reduced numbers at the local and state level. More recently, the party, while retaining its all-people’s front policy, has pledged to encourage communist candidacies and run for office where possible.

Present in all the developments is an ongoing tension between maintaining Marxism’s basic principles and applying them in ever changing conditions. How do you decide between what’s a primary question around which there can be no compromise and what’s secondary and open to negotiation?

Admittedly, it’s no easy question, as time and again theoretical foundation stones get traded away for seeming advantage. To gain votes, 19th-century socialists gave up key planks in their program. A few decades later, again currying favor, many of the same parties voted to support their government’s war efforts. World War II found the CPUSA’s leadership so taken with the task of building anti-fascist national unity that they traded away class independence for it.

This problem arises again and again: in Eurocommunism, in the Perestroika reforms, and post-Cold War, in the CP’s efforts to break out of narrow strictures and find relevance amidst calls to rethink its communist outlook, change its name, and even dissolve the organization.

But these pressures are unavoidable. Indeed, they are part of the living fabric of Marxism-Leninism itself, a doctrine whose views are continually tested, changed, and retested.

Clearly, care has to be taken in the course of these social tests that the very door that opens to new insights does not lead to the window through which basic principles are lost.

Concepts like the united front and the all-people’s front remain a living, breathing force in American politics. They have repeatedly come together in real life in the wake of Trump’s election: in the women’s marches, in the anti-police murder uprisings, in the sojourns from the uprisings to ballot boxes. The concept is not static: the all-people’s front is not an event, a meeting, a conference, but a series of meetings, events, conferences, demonstrations, marches, and occupations, over an entire period. It is the living, breathing mass movement of the people.

Drawing the lessons of its history and creatively applying them with flexibility while avoiding conceding working-class principles is key.

United and popular front forms will vary according to time, place, and circumstance: a housing coalition in one city, an alliance to prevent plant closings in another; a movement for reproductive rights in a third, an anti-war coalition to end the Russian invasion of Ukraine in a fourth. The Party should never be afraid to participate in, enter, or initiate coalitions. Indeed, it should be afraid not to. What it should really fear, however, is failing to stress the necessity of working-class leadership of these coalitions. As Gus Hall used to say: “Keep your eyes on the working class. You’ll make mistakes, sure, but you won’t make the big ones.”

Images: CP banners, CPUSA; Unity meme, CPUSA; UAW on strike, Al Neal, People’s World; Henry Winston, CPUSA; Friedrich Engels painting, Wikipedia (public domain); Lenin at 2nd Comintern; Georgi Dimitrov (on the right); Hall-Tyner campaign poster, CPUSA; Gus Hall, CPUSA; Poor People’s Campaign March on Washington, June 18, 2020, Erik Shilling.

Join Now

Join Now