The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again

By Robert D. Putnam with Shaylyn Romney Garrett (Simon & Schuster, 2020)

Is social, economic, and political history repeating itself? Robert D. Putnam, best known for his 2000 book Bowling Alone, and his co-author argue here that the contemporary U.S. has some remarkable parallels with the “Gilded Age” of the late 1800s. The upswing in the title refers to the positive strides made in the U.S. society, economy, and polity between the Gilded Age and the 1960s. Can we through deliberate action recreate some of those strides?

The strength of The Upswing is its marshalling of quantitative and qualitative data covering the last 125 years or so. The authors focus on four indicators: economic equality, public cooperation, cohesion of social life, and altruism in cultural values. Both now and in the late 1800s, there was more economic inequality, less public cooperation, less cohesion in social life, and less altruism in cultural values.

The authors devote a chapter to each of these dimensions, with clear indicators of each area graphed to show an upside-down “U.” For example, one measure of inequality takes the average total tax rate on the top 1% and subtracts the average total tax rate on the bottom half of the population. When illustrated, the upside-down “U” goes from a low of around 20% in 1910, to a high of 70% in 1960, and back to a low of 25% today. Other measures echo the same shape: gains and losses in minimum wages, regulation of financial markets, and union density. Even life expectancy, once seen as an inevitable upward slope, has begun to descend because of what economists call “deaths of despair” — fatalities due to opioid overdose, suicide, or alcohol abuse.

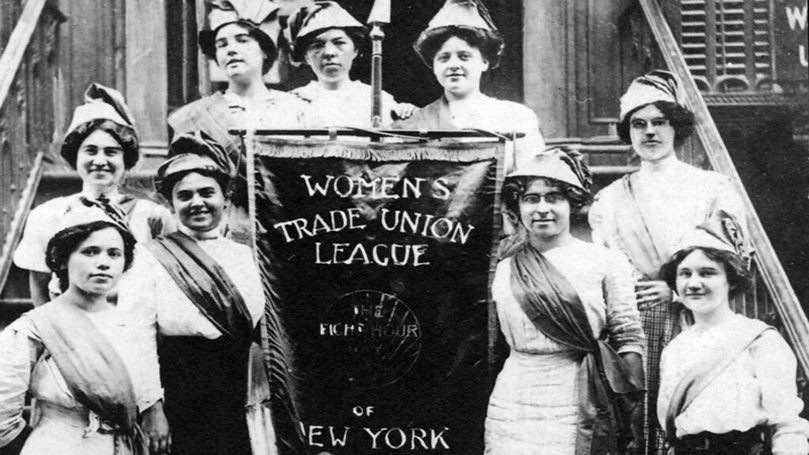

Cohesion in social life, the second area, is closely related to Putnam’s work in Bowling Alone, where he tracked the decline in membership associations of all kinds since the mid-1900s. Here he also views the period of increasing activism in the first half of the century. A “Club Movement” took place between 1870 and 1920 that saw the founding of numerous organizations, including women’s and African Americans’ fraternal groups. With more bell-shaped curve graphs, the authors show that the rates of membership in these groups reached its peak in 1960.

Cohesion in social life, the second area, is closely related to Putnam’s work in Bowling Alone, where he tracked the decline in membership associations of all kinds since the mid-1900s. Here he also views the period of increasing activism in the first half of the century. A “Club Movement” took place between 1870 and 1920 that saw the founding of numerous organizations, including women’s and African Americans’ fraternal groups. With more bell-shaped curve graphs, the authors show that the rates of membership in these groups reached its peak in 1960.

Public cooperation is a third component explored in a chapter entitled “Politics: From Tribalism to Comity and Back Again.” One measure inevitably is the partisan conflict that is so strong today. The authors argue that partisan loyalty was the weakest in the period around the second world war. Since then, one’s partisan affiliation has devolved into tribalism, as measured by, among other indicators, declines in friendships and marriages across party lines.

Fourth, in turning attention to cultural values over time, Putnam and Garrett contrast individualism and “communitarianism,” a term in sociology that refers to people putting their communities before themselves. Here the authors draw on quantitative data from “Ngrams,” which measure the incidence of given words per million words stored in Google Books. For example, the popularity of “survival of the fittest” reached a peak in 1890, compared to “social gospel,” which peaked in 1960. A graph of the Ngram for the phrase “common man” recreates the ubiquitous bell-shaped curve.

Robert Putnam is a Harvard sociologist, and he is not so naïve not to recognize some major complications to this simple upside-down “U” perspective. Chapters on race and gender explore how these dimensions introduce nuances missing in the “simplified microhistory” of the bell-shaped curve of 125 years of history. Many of the indicators in the race chapter, interracial marriage rates and Black Americans in U.S. Congress for example, trace steady upward trends instead of the familiar upside-down “U.” Furthermore, the text is about “trends and narratives, not certifiable causes.”

While their work on social change doesn’t benefit from a consciously historical materialist viewpoint, Putnam works in a discipline deeply influenced by Karl Marx, and he recognizes the ways that technological advances and changes in the economy reverberate throughout the other sectors of society.

The last chapter zeroes in on the work of several key movers and shakers of the Progressive Era who helped shape the upswing of the early 1900s: Ida B. Wells, Frances Perkins, and Walter Lippman among them. The authors find hope for progressive change in the grassroots organizations, especially of young people. While we might prefer an analysis that recognizes more clearly the concerted action of classes in shaping culture, politics, and social life, Putnam and Garrett’s book is a thorough and thoughtful analysis of patterns in a century-long arc of U.S. history.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Image: Women’s Trade Union League, 1910, Kheel Center (CC BY 2.0).

Join Now

Join Now