Given the current pandemic, spikes in unemployment, the looming threat of mass evictions, and questions presented by the recent Town Hall, it would be good to provide a brief history of the Unemployment Councils. While only a surface introduction, it provides a glimpse of what the Unemployment Councils accomplished. The councils were created and existed within great internal and external strife, and far more could be said while working with limited resources and space. A further and more comprehensive reading list is provided at the end.

Nearly 100 years ago, the fight for unemployment insurance as we know it today was just starting. Various cities at the time had some sort of unemployment relief, but their forms were often cruel and meant to deprive the worker of their self-worth.[1] With the workers already at starvation wages, the bosses, and the government officials they had in their pockets, simply could not just give unemployment relief and food for free because it would undermine the entire capitalist system as they knew it. Most who filed for “unemployment” were institutionalized in workhouses or never received relief. This started to change with small groups on a local level as they started to organize in the 1920s. Some groups started prior but were often nothing more than rioting workers during panics and downturns (19th-century recessions) and did not gain mainstream traction until the Great Depression.

Without a stable system in place and with Hoover’s starvation policies, unemployed workers often turned to ineffective breadlines and waited en masse to apply for a single open position. It is here the Communist Party USA began to lead the charge. Together with the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) and the Young Communist League (YCL), communist organizers directed workers to march on city halls, take direct action, demand relief from elected officials, and bring together people in the tens of thousands, while the A.F. of L. and Socialist Party fell in lockstep with Hoover’s general line of inaction.[2] At a time of great uncertainty and strife, how could they not demand relief and accountability?

Before the 1929 stock market crash even happened, the Communist Party USA had been organizing heavily in the 1920s. As early as 1924 the Communist Party and its Central Committee saw the sandy foundation of U.S capitalism for what it was and, as early as 1927, witnessed the cracks appearing in the capitalist system.[3] Growing its membership and taking leading roles in worker and union movements, the Party was able to influence and guide organizations to action. They started in areas where they had the strongest presence, organizing mass demonstrations and marches. As soon as March 6, 1930, the Communist Party through TUUL was able to organize 1,250,000 people to demonstrate in cities across the nation.[4] This initial success did not find the stable footing the Party had hoped for. While some success was documented, it was not until the Fall of 1930 when—in a shift from abstract to practical demands, developed with help of the Comintern—the Party found its real strength.[5]

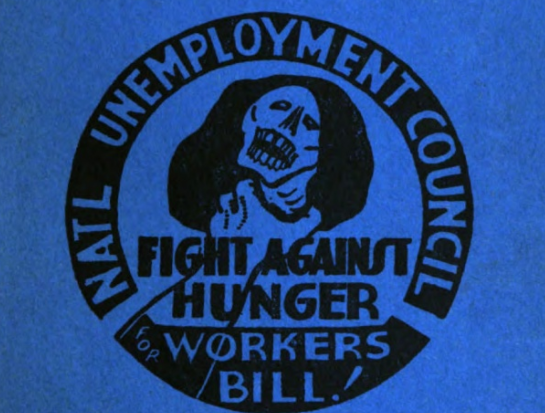

Further organization manifested itself by bringing pressure on employers, local relief boards, cities, states, and the national government. On May 1, 1930, declared the first National Unemployment Insurance Day, mass demonstrations were organized as Hunger Marches, with the first one resulting in a total of 350,000 people demonstrating nationwide. This was only one-third the number of participants in the Unemployment Day protests that occurred two months prior on March 6, but a year later, 400,000 marched, and 500,000 in 1932.[6] Organizers brought thousands from cities to Washington, D.C., where they marched through the streets with clockwork precision, bringing with them petitions and blasting the “Internationale” on the plaza before the Capitol, forcing thousands of police to be called in and troops at various forts to be set on alert.

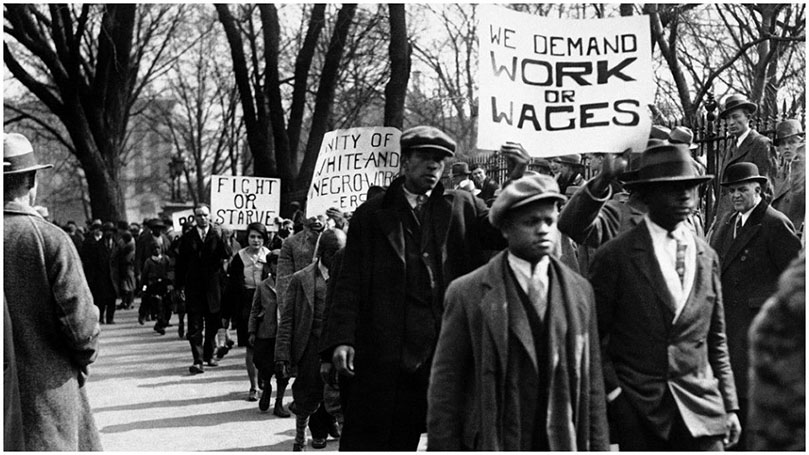

The Unemployment Councils established nine basic demands.[7] Food and shelter, however, became the immediate, tangible demands. Those without employment were unable to buy what was needed and were forced into starvation. It was these conditions that drove the recently established Unemployment Councils to take action into their own hands. Food distribution was essential. One approach in 1930 led to 1,100 men in a breadline emptying two trucks delivering baked goods to a hotel across the street. They rushed the trucks and took the food for themselves, their families, and others in need. These acts were not spontaneous; this was organized seizure of necessary goods, the expropriation from the wealthy in favor of the poor.[8] Demonstrations also occurred throughout large cities as workers carried Communist Party banners declaring “Work or wages!” or “Fight—Don’t Starve!” in the thousands. While not dissimilar to actions taken in previous decades, their organizational structure achieved greater results across the nation.

Organization around rent relief and evictions was equally effective at providing material aid for underemployed and unemployed workers. Communist organizers led small bands of people to forcibly stop company workers and city marshals from enforcing evictions and moving out families’ furniture and belongings. In doing so, the communists restored 77,000 homes to evicted families in New York alone.[9] When not helping families back in their homes across the country, they forced mayors and officials to order moratoriums on evictions and various bill payments. While these workers and organizers faced arrest, tear gas, beatings, and even death, it was their actions that made cities and public organs pay attention to the crisis around them. Beyond fighting evictions and procuring food, communists demanded emergency relief, both monetary and physical. They won relief in the forms of rent, food, medical care, clothing, employment, and comfort items (toys, books, tobacco, etc.) and even prevented cuts to previous victories.[10]

These efforts were nationwide, from the West Coast to the East Coast, Deep South to the frozen North, rural to urban. In the South however, they faced further resistance from the KKK and other terrorists while attempting to organize and bring together black and white workers. While landlords were raising rent, cotton prices were falling. To combat this, the communists took similar actions as they had in New York, marching hundreds of black and white sharecroppers to local planters and merchants demanding food and relief while establishing the Share-Croppers Union.[11] In other rural areas, the communists helped farmers organize milk strikes and “penny sales,” where foreclosed farms were bid on by the family for a penny, thus preventing anyone else from going above that bid.[12]

Equally important as providing aid and security for those unemployed and without the bare necessities was facilitating solidarity between the employed and unemployed. The Big Strike Movement of 1934–36 started organizing a year earlier, as the Communist Party and TUUL saw the A.F.L’s strategies and tactics as ineffective and insufficient. Organizers brought unemployed and employed workers together in solidarity, strengthening their resolve. Using sit-down strikes, slow-down strikes, mass pickets, and other methods, they led nearly 1.5 million strikers in 1934, 1.2 million in 1935, and 800,000 in 1936.[13] During these years, the National Unemployment Councils were on the picket lines with the workers and offered what aid they could while continuing to agitate for unemployment relief.

However, not all attempts to better the conditions of the working class during the Great Depression were organized by the Communist Party. The Socialist Party, Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA), League for Industrial Democracy, and others also had similar organizations. Some began under the CPLA, and membership in their own short-lived Unemployment Leagues reached 80,000.[14] For all the disagreements the various parent organizations had, they all saw the need to organize locally to further demands. These groups met in various conventions with, and without, each other, further consolidating efforts throughout the early 1930s.

These consolidations grew larger in size, often at the proposal of the communists. In 1936 the Unemployment Councils, the Workers Alliance, and the National Unemployment League formed the Workers’ Alliance of America (WAA), which boasted 600,000 members and 1,600 locals, reaching 800,000 members by 1938.[15] The Workers Councils provided immediate relief to those most in need through grassroots organizing and direct action. Led by the Communist Party USA, their militant outlook and radical program offered the strongest relief efforts the working class had to offer each other during trying times. Retaining an influential role in the WAA, the communists ensured that its militancy remained, and it continued to demand unemployment relief and direct support for fellow workers, a subject deserving of its own article.

Currently, COVID-19 continues to spread, causing runs on masks and other medical supplies, even industrial. With states placing operational restrictions on many service-sector industries, workers are seeing reduced hours and wages or are completely laid off. In addition, few companies have updated their sick leave policy to promise full pay to those calling off work amid these concerns. Unemployment filings reached 10 million just for the month of March. Additionally, undocumented workers will not receive federal aid despite paying taxes much like everyone else. This virus is projected to bankrupt more people than it will kill. Given the straining economy and the omnipresent threat of another recession warned by economists, perhaps it is time to bring back the unemployment councils—to create communities that will protect and help one another as the capitalist system ultimately fails once again.

For further reading and source material please see:

Daniel Leab “United We Eat: The Creation and Organization of the Unemployed Councils in 1930.” Labor History 8 (1967): 300–315.

Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward. Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Harvey Klehr. The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Robin D. G. Kelly. Hammer and Hoe, Alabama Communists during the Great Depression. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

William Z. Foster. History of the Communist Party of the United States. New York: International Publishers, 1952.

Roy Rosenzweig. “Radicals and the Jobless: The Musteites and the Unemployed Leagues, 1932–1936.” Labor History 16 (1975): 52–77.

Irene North. “Communist Party Theory and Practice among the Unemployed, 1930–1938.” Marxists.org.

Fighting Methods and Organization Forms of the Unemployment Councils (1932). Marxisthistory.org.

Constitution and Regulations of the Unemployment Councils (1934). Hathitrust.org.

[1] Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

[2] William Z. Foster, History of the Communist Party of the United States (New York: International Publishers, 1952), 280–281.

[3] Foster, History of the Communist Party, 278.

[4] Foster, History of the Communist Party, 282.

[5] Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 52–53.

[6] Foster, History of the Communist Party, 283.

[7] “(Proposed Draft) Program: Fighting Methods and Organization Forms of the Unemployment Councils: A Manual for Hunger Fighters,” Marxist History, 1–3.

[8] Piven and Cloward, Poor People’s Movements, 49.

[9] Ibid., 54.

[10] Ibid., 59.

[11] Foster, History of the Communist Party, 283.

[12] Foster, History of the Communist Party, 283–284.

[13] Ibid., 299.

[14] Piven and Cloward, Poor People’s Movements, 70.

[15] Piven and Cloward, Poor People’s Movements,76; Foster, History of the Communist Party, 299.

Image: March 6, 1930: Unemployed Council gather in front of the White House in Washington before a major protest for International Unemployment Day. CPUSA Archives.

Join Now

Join Now