Bill Davis, a long-time trade union and peace activist and Communist Party USA leader, died Jan. 23 in New York while in hospice with COVID-19. He was 78 years old.

Davis was a caseworker for the New York City Department of Welfare (later Social Services) and a fixture in the trade union movement. As an AFSCME Local 371 member, he was elected shop steward to the local’s Executive Committee, one of the local’s delegates to the NYC Central Labor Council, and an active retiree.

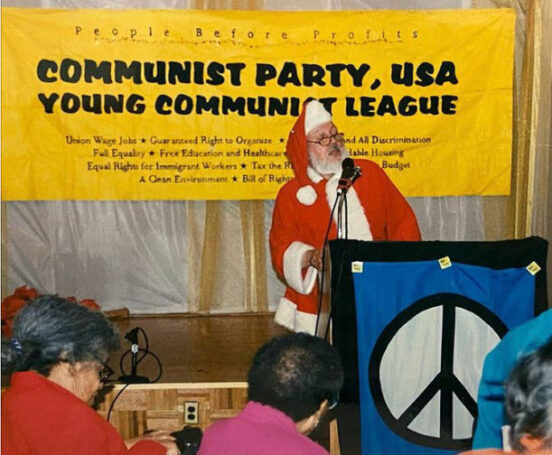

He was loved for his empathy, generosity, and kindness. He often dressed in a blue work shirt (with a red tie on special occasions), red suspenders, a bulging pen protector, and carried the latest technological gadget. He delivered his renowned wit or made a point with his eyes dancing and peering over reading glasses resting on the edge of his nose bridge. And each holiday season, he delighted scores of children by dressing as Santa Claus.

Born in 1942, Davis grew up on a 49-acre family farm in Pitcher, a tiny town in central New York. His father was a sheet metal worker and union member. His mother worked in a variety of office jobs, eventually becoming the town’s postmaster. He was the oldest of seven children who all worked the farm to supplement their income, raising vegetables, dairy cows, and livestock for slaughter. His working-class upbringing and growing up amidst poverty-stricken neighbors helped shape his sense of justice and modesty.

Born in 1942, Davis grew up on a 49-acre family farm in Pitcher, a tiny town in central New York. His father was a sheet metal worker and union member. His mother worked in a variety of office jobs, eventually becoming the town’s postmaster. He was the oldest of seven children who all worked the farm to supplement their income, raising vegetables, dairy cows, and livestock for slaughter. His working-class upbringing and growing up amidst poverty-stricken neighbors helped shape his sense of justice and modesty.

The Davis children learned to hunt early, including deer on the family farm. Each year, Davis would spend a weekend during deer season with his brothers and step-father, returning to New York City with venison. He made a mean spicy stew known to burn the roof of an unexpecting eater’s mouth.

Davis was accepted to attend both Harvard and Columbia. The latter offered him a scholarship as part of an effort to bring more rural youth to the university, so off he went in 1960. He left Pitcher a conservative Republican and once on campus joined the Young Republican Club. But his experience at Columbia—becoming part of a diverse community and student body and becoming engulfed by the 1960s activist upsurge of the Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam war movements—quickly opened his eyes.

After graduating from Columbia in 1964 with a degree in psychology, Davis got a job in the NYC Department of Welfare. He was drafted into the U.S. Army shortly after. The U.S. was in the middle of the massive troop build-up in the war against Vietnam. He was stationed at a military hospital in Germany, working with soldiers with mental health issues. After discharge, Davis traveled across Europe, at which time he grew the beard he wore the rest of his life.

Perhaps it was the hospital experience that helped develop Bill’s great sense of empathy. Later, as a Communist Party leader in New York, Bill’s door was always open to the broadest assortment of people, listening to their stories while giving support.

Upon discharge, Bill returned to his job with the Department of Welfare. He became a caseworker, working with the city’s adult, family, and homeless populations. Upon his retirement in 1995, he was the tuberculosis unit supervisor at the Bellevue Hospital men’s shelter.

During college, Bill met Joan Feder, and they married on Leap Year Day, 1968. Joan graduated from Columbia with a degree in chemical engineering, receiving a scholarship to increase women in the field. At first, Joan’s Jewish family resisted the marriage proposal, even after Davis offered to convert to Judaism. But when the couple’s daughter, Angela (named for Angela Davis), was born in 1971, all was forgiven.

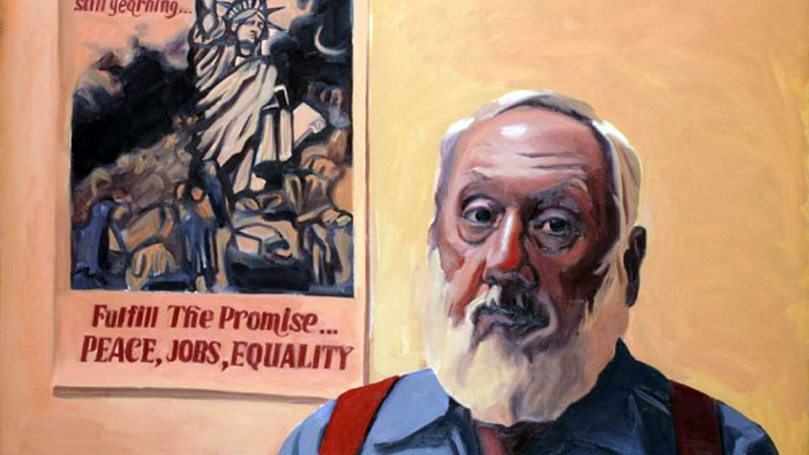

Throughout this period, Bill continued to become politically radicalized. “I also began seeking a political organization which would deal with the social and economic inequities and problems I saw in the U.S. I joined the Communist Party USA in 1971 after meeting comrades active in my union,” Davis told artist Yevgeniy Fiks in a 2007 interview. His family joined him at many protests. “I thought that’s what you did—go to demonstrations,” recalled Angela.

The Davis family lived in a Mitchell-Lama Cooperative Housing building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Residents there reflected the city’s diverse population. Bill and Joan made lifelong friends among the tenants through a consciousness-raising group and activism in the community.

In 1976, the family moved to the racially integrated community of Laurelton, Queens. Laurelton was experiencing redlining and white flight as African American and Latino families moved in. The Davises joined a multi-racial group of residents working to preserve integration.

In 1976, the family moved to the racially integrated community of Laurelton, Queens. Laurelton was experiencing redlining and white flight as African American and Latino families moved in. The Davises joined a multi-racial group of residents working to preserve integration.

The movement included sit-ins demanding a new high school planned for the border with predominantly white Rosedale be integrated. Rosedale resisted and built offices on the land instead.

Davis was arrested in numerous civil disobedience protests over the years against police brutality, U.S. military aggression, and apartheid in South Africa.

During the 1990s, Bill and Eddie Davis (no relation) played an essential role in keeping the May Day tradition alive in New York City. They led a committee that included unions, social justice organizations, artists, and activists. They also led a movement to pass the Martinez Jobs and Infrastructure Act, gathering hundreds of endorsers, lobbying, and holding rallies.

He was elected to the CPUSA National Board and National Committee and served as the party’s New York District Organizer. Davis was also active in the Working Families Party, Left Labor Forum, and Veterans for Peace.

In 2002, Joan Feder tragically died from cancer. One of Bill’s friends helping him through the grieving process was co-worker Esther Moroze. They fell in love and married in 2008 and since then shared the joy of activism and comradeship. They hosted a renowned New Year’s Day open house, continuing a tradition that started in Laurelton. They attended demonstrations together, including before the pandemic, even though Davis was increasingly limited in mobility because of Parkinson’s disease.

“Bill loved to pass out People’s World,” recalled Esther. “As soon as we got to a demonstration, he would disappear with a bundle of papers, and I wouldn’t see him again until it was time to leave.”

Davis was also an accomplished journalist. His most notable works included vivid reports of labor struggles in Australia and New Zealand during a speaking tour in the 1990s.

Davis’s grandfather bequeathed him an 18-acre woodlot near the farm. He bequested the land be returned to the Onondaga Nation, one of the five original Indigenous nations of the Iroquois Confederacy and the original inhabitants of the upstate area.

Davis donated his personal papers to the Tamiment Library at NYU, which houses the CPUSA archives. When the chief librarian expressed excitement over the donation, Davis modestly asked, “Why would they want my papers? I’m not an important person.” He was honored for lifetime activism at the People’s World Better World Awards event in 2014.

Besides his wife and daughter, Davis is also survived by two step-sons, Marc and Dan Auerbach, six siblings, and nine nieces and nephews. His friends and comrades will miss him but are thankful he enriched their lives. In his memory, donations can be made to People’s World, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, or Veterans for Peace, NYC chapter 34.

Published in People’s World, Feb. 16, 2021.

Images: top, portrait of Bill Davis at CPUSA headquarters in New York, 2007, oil on canvas, by Yevgeniy Fiks; Bill Davis as Santa Claus at a Communist Party USA holiday open house, 1990s, People’s World Archives.

- Tags:

- Bill Davis

Join Now

Join Now