It was December 6, 1932. The U.S. Vice President, Charles Curtis, was clearly distraught. Thousands of Hunger Marchers led by the Communist Party, USA, had just finished parading down Pennsylvania Avenue demanding unemployment insurance and jobs, and they now beckoned Curtis’ attention—as well as House Speaker and Vice President–elect John Garner.1

That millions had participated in National Unemployment Day marches across the country since the start of the Great Depression,2 with tens of thousands joining the communist-led Unemployed Councils,3 only added to Curtis’ discomfort. That a handful of unemployed workers—unceremoniously demanding relief and jobs—were now addressing the life-long politician with petitions in hand was too much for Curtis to bear. That a 21-year-old firebrand, Anne Burlak, already a union officer and Rhode Island Communist Party leader, was at the helm of the delegation addressing Curtis4 made the Kansas-born vice president lose his composure. Curtis barked, “Just hand me your petition . . . I only have a few minutes.”5

Simultaneously, Herbert Benjamin—the national head of the Unemployed Councils and CPUSA leader—along with African American Chicago-area Party leader Claude Lightfoot, met with Vice President–elect Garner. That an interracial, male-female delegation of open communists—Burlak, Benjamin, and Lightfoot—could compel a meeting with two of the most powerful men in the nation in 1932 forced a hard realization. For at that moment, a reality rarely acknowledged by those in the hallowed halls of political power became painfully apparent: the communist-led unemployed movement, as William Z. Foster so eloquently put it, had “startled” the nation and made the CPUSA “a major political force,” a force that had to be reckoned with, which easily explains Curtis’ discomfort—that, and the band of unemployed musicians playing the “Internationale” just outside.6

The Daily Worker would later call the march “a splendid victory” for the unemployed and “a striking defeat” for Washington’s “hunger government.” In fact, the anti-communist historian Harvey Klehr begrudgingly agreed with the Daily Worker’s sentiment. “The communists had reason to be pleased,” he wrote. “They had garnered national publicity, forced the government to back down, and avoided violence.”7 Curtis and Garner had undoubtedly seen better days.

Throughout her long life, Anne Burlak Timpson would prove to be what Foster called a “political force.” Born on May 24, 1911, in Slatington, Pennsylvania, Burlak was the eldest of six children of Ukrainian immigrants. To help support her family, she dropped out of school at age 14 and began working in the mills,8 usually over 50 hours a week for as little as $9.9 By 1926, after meeting the legendary communist Ella Reeve “Mother” Bloor, Burlak joined the Young Communist League. By age 17 she was already “represent[ing] workers from her Bethlehem plant” at the first convention of the communist-led, Trade Union Educational League–affiliated National Textile Workers’ Union (NTWU).10 She was later arrested at a Bethlehem protest for reading the Bill of Rights and “blacklisted.”11 Burlak also attended the founding convention of the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) and was elected to its Women’s Council.12 Burlak would later write:

My class struggle education developed rapidly. Daily experience in the mill taught me that my boss and I had nothing in common. He was looking out for ever more profits, which he could only achieve at his workers’ expense. We were anxious to increase our wages, which we could accomplish only if our boss would part with a bit of his profits.13

It is around this time, after being “arrested and charged for spreading Communist propaganda under [Pennsylvania’s] sedition laws,” that Burlak decided, “I might as well join the Communist Party and learn more about it.” The sedition case was eventually dropped, and Burlak went to work for the NTWU as a full-time organizer. By early 1930, Burlak had gone south to the Carolinas and then to Georgia.14

Anne Burlak, now almost 20 and on her own—her father had been blacklisted as well, and unable to find work moved the rest of Burlak’s family to the Soviet Union—threw herself tirelessly into organizing “multiracial textile unions in the South—a dangerous undertaking that led to death threats and prison time.”15

In fact, on May 21, 1930,16 at a “rally against unemployment and racism”17 sponsored by the Party-led American Negro Labor Congress,18 Burlak and three other speakers, including two African Americans, were arrested for defiantly challenging Georgia’s segregation laws. Charged with “attempting to incite insurrection, as defined by a pre-Civil War law,”19 Burlak had originally gone to Georgia under the auspices of the NTWU to organize workers at the Atlanta Woolen Mill and the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill, considered “two of [the area’s] harshest employers”20 in a city known as “one of the most reactionary cities in the South.”21 Now in jail—her future uncertain, as Georgia’s Insurrection Law carried the possibility of a death sentence22—Burlak and the others were joined by fellow communist M. H. Powers and YCL member Joe Carr; both had been thrown in jail on similar charges. Together, they became known as the “Atlanta Six.”23 The Southern Worker would later call the struggle to free the Atlanta Six a “fight of the entire working class” that expressed the “clear class struggle policies of militant labor against unemployment . . . [and] exploitation.”24

After six weeks in jail, Burlak was released25 and quickly began touring the country, “mobilizing support”26 for her comrades still locked up. It would be seven years27 before the United States Supreme Court would hear Burlak’s case, which had been joined with that of Angelo Herndon, another well-known communist, who had been arrested under the same insurrection law. Ultimately, the high court would declare the Georgia statute “unconstitutional.”28

However, while still touring in support of the Atlanta Six, Burlak attended the American Federation of Labor’s 50th National Convention where she was stunned by then AFL president William Green’s sense of detachment, as he “argued against a national system of unemployment insurance”—an issue that would come to define Burlak’s life in the very near future. “It was hard for me to imagine a labor convention opposing federal unemployment insurance in the face of the mass misery and hunger in the land,” Burlak would later comment.

The firebrand didn’t mince words. As far as she was concerned, Green and the AFL leadership were more concerned with “address[ing] bankers, politicians and mill owners” than textile workers. Green “was wined and dined by Chambers of Commerce, who received him politely” as he “painted the horrors of ‘communist’ organization as an alternative”29 to the conservative, pro-business AFL. That Steve Nance, the anti-communist Georgia Federation of Labor president, served as assistant secretary of the grand jury that indicted Burlak—and the other three Negro Labor Committee (NLC) speakers—only added to Burlak’s jaundiced view. The International Labor Defense (ILD) went so far as to suggest a “connection between the prosecutor’s office and the fascist forces of the [Georgia] AFL.”

Not all of Georgia’s labor movement shared Green and Nance’s view, though. Mary Baker, the Atlanta-based “militant president” of the American Federation of Teachers, argued, “[I]f they [can] railroad Communists for organizing workers, they can do the same to any other labor organizers.”30

Unlike much of the AFL’s leadership, the communist-led NTWU, actively “link[ed] workplace issues to larger societal issues. In the South, this meant the call for racial justice; in New Bedford, [Massachusetts] where Burlak was [now] sent . . . it meant [fighting for] the rights of the unemployed.” “Our union helped to organize a couple of Unemployed Councils, offering our Union Hall as a place for the Councils to hold their meetings,” Burlak added. “Our Union considered it vitally necessary to maintain close relations between the workers in the mills, and the unemployed workers. So we organized regular mill gate rallies, to discuss the need for unity and joint action around such demands as ‘adequate relief,’ and for ‘federal unemployment insurance to laid off workers.’”31

By spring 1931, Burlak was in Rhode Island, where “strikes were brewing.” By May she had “assumed leadership” of the striking mill workers in Pawtucket. According to the Young Worker, the publication of the Young Communist League, the mill workers were “[r]evolting against starvation wages of five and eight dollars a week for a 44 to 48 hour week” and demanding the removal of “efficiency experts.”

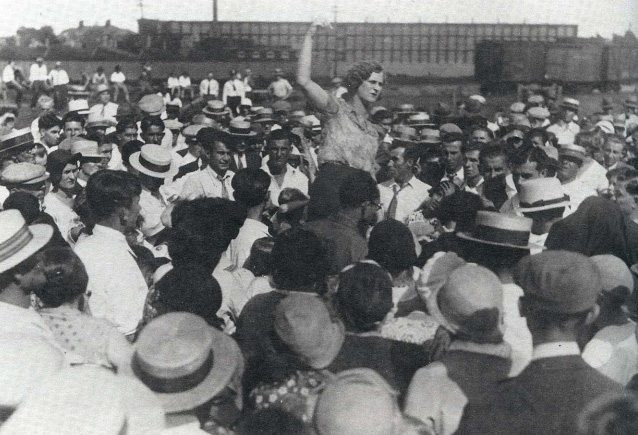

In mid-June, after the mobilization of “every officer in the city” of Central Falls, Burlak, the “girl striker,” was arrested for allegedly assaulting a forelady at the General Fabrics Corporation. Undeterred and “vehemently denying” the assault charge, Burlak conducted her defense at the trial. As “five hundred strikers gathered outside of the courthouse,” Judge Roscoe M. Dexter declared Burlak guilty and sentenced her to 30 days in jail and a $200 fine. In mid-July, on the same day as her release, 3,000 strikers and supporters marched to the Central Falls silk mill. When Burlak appeared, greeted by cheers, the strikers “broke through police lines.” Local papers called the action a communist “invasion,” and on July 12, just one day after her release, state police informed Burlak that she had to leave Central Falls. “Sure, I’ll go now,” she replied, and “promptly” crossed the bridge back to Pawtucket. The New York Times credited Burlak with doing “more than any one else to keep up the spirit of the strikers.”

While the conservative AFL leadership attacked the NTWU as “an organization whose purpose, it has been demonstrated, is inimical to the aims, objectives and ideals of our labor movement, and is also destructive to our American institutions,” the Central Falls and Pawtucket mill workers considered the communist-led NTWU and Anne Burlak “the storm center of the strike.” The AFL clearly took issue with the reality that strikers “placed their confidence solely in Burlak,”32 a well-known woman communist, and not in the AFL-affiliated United Textile Workers (UTW) union, well known as “one of the most incompetent [unions] in the labor movement.”33

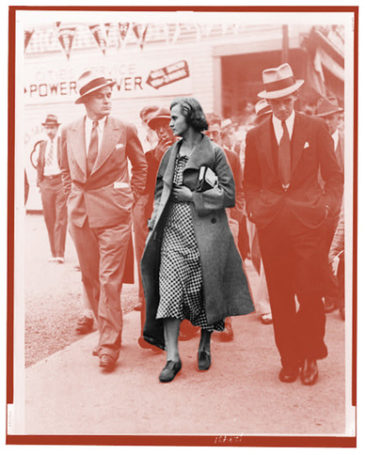

On July 15, federal immigration authorities “arrested and attempted to deport” Burlak. Labeled an “undesirable alien,” due to federal officials’ inability to find her Pennsylvania birth certificate, Burlak couldn’t help but be amused, and asked rhetorically, are there “no Americans that are fighters . . . [do] they all have to come from somewhere else.” The CPUSA and the NTWU denounced the attempt “to intimidate the strikers” through terror, arrest, and threatened deportation.34 Under a photo of Burlak waving as she was released from custody, the Young Worker put the matter simply: Burlak had been arrested “in an attempt to frighten the foreign born strikers” and called the assault on workers a “terror drive.”35 Fortunately, Burlak’s ILD lawyer presented “a copy of her baptismal certificate, sufficient proof that she was an American.” Released on July 21, Burlak quickly got back to work. She “addressed 1,500 strikers” in Pawtucket and then, “accompanied by a group of 150 supporters,” went to Providence, Rhode Island, “where she exhorted strikers from the Weybosset Mill . . . not to return to work.” Unfortunately, though, the strike was “effectively lost,” as nearly half of the workers soon returned to the shop floor, and the “troublemakers” were “told not to return.”

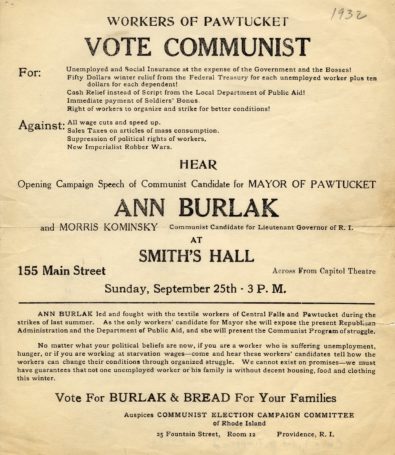

By spring 1932, Burlak had refocused her energy into electoral politics by running for mayor of Pawtucket on the Communist Party ticket. One Burlak campaign flyer urged, “We cannot exist on promises—we must have guarantees that not one unemployed worker or his family is without decent housing, food and clothing this winter. Vote For BURLAK & BREAD For Your Families.” While she did poorly at the polls, her campaign undoubtedly forced other candidates to address issues that otherwise would have been ignored.

After the 1932 elections and Roosevelt’s victory, Burlak shifted her priorities back to more familiar terrain, the direct struggle for workers’ rights. As the newly elected national secretary of the National Textile Workers’ Union—“the only women to hold such a high union post”—Burlak helped draft the textile industry’s National Recovery Administration code and participated in Congressional hearings where she proposed language “preventing discrimination based on race, sex or creed,” which was quickly rejected by the conservative lawmakers.

Burlak declared, “The workers are not going to wait until the government or arbitrators settle things for them. . . . . The workers are striking now and they are going to strike, and they will be led by the National Textile Workers.”36 Two short years later, nearly half a million textile workers across the country went on strike. Burlak proved to be both right and wrong in her projections. Ultimately, the AFL-affiliated UTW benefited from the tremendous upsurge, as its membership swelled from 27,500 to 270,00037—not Burlak’s NTWU.

Ironically, once Section 7a of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which granted millions of workers the right to bargain collectively, became law Burlak found herself and her union increasingly isolated. Radical, communist-led unions like the NTWU were passed over in favor of more mainstream unions within the AFL. As the Pawtucket Times put it, “President Roosevelt [by signing the NLRA] has done what police, state courts and federal labor and immigration authorities were powerless to accomplish. He has, for the time being at least, squelched the formerly irrepressible Ann Burlak, discrediting her in the eyes of hundreds of her erstwhile followers here.”

Adding insult to injury, under Green’s leadership the AFL took “strong measures” to actively “prevent radicals like Burlak from even speaking to strikers.” Taking a cue from local business owners, the conservative AFL leadership went so far as to petition police to bar Burlak from strikes and followed her everywhere, refusing to let her organize, talk with workers, or participate in rallies. According to Quenby Olmsted Hughes, “The very press coverage that helped to catapult [Burlak] to prominence in the early 1930’s, and brought attention to issues of significance to the Communist Party, also helped to limit her role as fears of radicalism increased.” In short, Olmsted Hughes argues, “New Deal legislation legitimized less radical options to Burlak’s Communist unions.”38

By March 1935, the communist-led Trade Union Unity League—of which the NTWU was an affiliate—had dissolved.39 A number of factors led to its dissolution, including a “somewhat reinvigorated AFL” and the emergence of a new labor federation, the Committee for Industrial Organization—later the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Communists like Burlak—due to the “excellent training” they received in the TUUL—became “a major force” within the CIO and “play[ed] a foremost role in the great [organizing] triumphs” to come.40 Additionally, the passage of the NLRA—and its impact on labor, generally—“placed sharply before the communists the necessity of intensifying their work” within the AFL, thereby “infusing a new militancy”41 while challenging the conservative old guard. Essentially, the Communist Party re-evaluated the necessity for independent, radical trade unions like the NTWU due to these changes, and thereafter shifted away from “Third Period” red unions. Prior to its dissolution, the TUUL could boast an “affiliated membership of 125,000,”42 as well as a unique and proud commitment to racial equality. Not only did the TUUL demand an end to “organized lynch and murder terror against the Negro masses of the South,”43 it also “agitated for black-white unity and special attention to the needs of black workers” through the “open defiance of Jim Crow,” desegregated unions, and biracial workers’ juries.44

Born out of the Textile Mill Committee of the New Bedford, New Jersey, strike45—which Burlak participated in46—the NTWU’s membership is more difficult to gauge. During that strike the NTWU enrolled 6,000 new members.47 However, its membership fluctuated dramatically. Officially founded in September 1928,48 the NTWU initiated and led numerous strikes—including the 1929 Gastonia, North Carolina, strike of 2,000 and the 1930 Lawrence, Massachusetts, strike of 10,000 to 12,000, among many others—leading thousands of textile workers to join the communist-led union, if only temporarily. According to a 1931 Bureau of Labor Statistics report, this “new group, of ‘left wing’ inception [the NTWU], did not report its membership, but it is considered to be drawing, temporarily at least, upon the disaffected elements”49 of other unions, as well as women and African American textile workers—whom the UTW were loath to organize. While tens of thousands of textile workers—those recruited during the strikes—passed through its ranks, by early 1932 the NTWU counted roughly 2,000 members.50

Undoubtedly, competition with the UTW, “mass hysteria, mob violence, and sheer hunger,” as in the Gastonia strike,51 as well as anti-communism, resulted in few long-term victories—or long-term dues-paying members. Not only did the NTWU lead “a struggling half-life, with few resources,”52 it also faced ongoing challenges from the “conservative, conventional, [and] accommodationist” UTW.53 By January 1933 the NTWU had “virtually disintegrated” and counted 700 to 800 members.54

As the Communist Party shifted gears due to the new political realities, so did Burlak. As part of a series of New England speaking engagements, she visited Yale, Harvard, Amherst, and Bates among other colleges. At Vassar—along with representatives from the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union, and the Petroleum Council—she spoke at an “Economic Conference centering upon the general subject of labor and the N.R.A. [National Recovery Administration].” Burlak “bitterly and emotionally indict[ed] the administration for its failure to have bettered, in any way, the conditions of the American worker.” She went on to call the NRA a failure, as it did not do enough “to remove the cause of the [economic] crisis, which was overproduction; to reopen factories and restore normal production; to reduce unemployment to the lowest possible figure; to raise wages and shorten hours as much as possible; and to secure for Labor a free and untrammeled right of organization.”

According to Burlak, “The N.R.A. program is rapidly growing into a war program, and it will be Labor who will pay for the war!” She went on to denounce the “Labor Representatives,” like AFL president Green, on the National Labor Board: “They have no more connection with Labor than I have with Capital.” “I am a Red,” she added, “and a Red has got to be shown.” Burlak demanded “proof” of labor’s rights. “I know it is not true. There are no democratic rights. The only way Labor can get what it needs is to organize—no—not just organize, but go out and strike, fight to get its demands. The only time our employers will talk to us is when we have their machines stopped, and their factories closed down. And we know it” (italics in original). She concluded by saying the NRA is “driving thousands of people back to misery.”55

Burlak’s presence on college campuses came to an end in 1936, as she left for Moscow to attend the International Lenin School,56 designed to train “leading cadre for the Communist International.” As one of roughly 200–225 U.S. students to attend the Lenin School during its 12-year history,57 Burlak undoubtedly studied Marxism-Leninism, organizational techniques, and Soviet history, as well as international solidarity.

Also in 1936, after leaving the Soviet Union, Burlak volunteered to fight Franco’s fascists in Spain as part of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a volunteer contingent of over 3,000 anti-fascist Americans—mostly communists.58 She returned to the U.S. in fall 1939 and became the Massachusetts Communist Party executive secretary, where she concentrated mostly on local issues and edited a local Party newsletter, the Roxbury Voice. In 1956, as one of the last Americans to be arrested under the unconstitutional Smith Act, she was charged with conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government. She was arrested again in 1964 under the provisions of the McCarran Act, which were also found to be unconstitutional.

In 1982, Burlak was awarded the Wonder Women Award from the Wonder Women Foundation in New York, and in 1997 she was given the Sacco-Vanzetti Memorial Award from the Community Church of Boston. Burlak remained an active member of the Communist Party, USA, until the end of her life. She died on July 9, 2002. In 2005, the Anne Burlak-Timpson Labor Forum was established in her memory, and awarded its first Red Flame Award to the United Farm Workers’ founder, Dolores Huerta.59

Notes

1. “Red Flame Burning Bright: Communist Labor Organizer Ann Burlak, Rhode Island Workers, and the New Deal,” by Quenby Olmsted Hughes, Rhode Island History 67, no. 2 (Summer/Fall 2009): 50; Women and the American Labor Movement: From World War I to the Present, by Philip S. Foner (The Free Press, 1980), 267, 268; Impatient Armies of the Poor: The Story of Collective Action of the Unemployed, 1808–1942, by Franklin Folsom (University Press of Colorado, 1991), 338.

2. History of the Communist Party of the United States, by William Z. Foster (International Publishers, 1952), 281, 282.

3. The Communist Party of the United States: From the Depression to World War II, by Fraser M. Ottanelli (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 32.

4. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 50. Historian Philip Foner documents a slightly different version of events. He writes that Burlak met with Speaker Garner, not Curtis in Women and the American Labor Movement, 267, 268. Franklin Folsom also writes that Burlak met with Garner. Impatient Armies of the Poor: The Story of Collective Action of the Unemployed, 1808–1942 (University Press of Colorado, 1991), 338; Chicago communist Claude Lightfoot writes in his autobiography that he and Herbert Benjamin met with Garner, which would seem to support Olmsted Hughes’ version of events. See Chicago Slums to World Politics, by Claude Lightfoot (New Outlook Publishers, no date), 46.

5. Impatient Armies, 338.

6. Chicago Slums, 46; History of the Communist Party, 281, 282; Henry Winston: Profile of a U.S. Communist, by Nikolia Mostovets (Progress Publishers, 1983), 18.

7. The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade, by Harvey Klehr (Basic Books, 1984), 67, 68.

8. Biographical Note, Anne Burlak Timpson Papers, Five College Archives & Manuscripts Collections.

9. Women and the American Labor Movement, 238.

10. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 45.

11. Linked Labor Histories: New England, Colombia, and the Making of a Global Working Class, by Aviva Chomsky (Duke University Press, 2008), 84.

12. “Anne E. Burlak Timpson: May 24, 1911–July 9, 2002,” by Evelina Alarcon and John Pappademos, People’s World, July 19, 2002.

13. Linked Labor Histories, 84.

14. Biographical Note, Anne Burlak Timpson Papers.

15. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 45.

16. Biographical Note, Anne Burlak Timpson Papers.

17. America before Welfare, by Franklin Folsom (New York University Press, 1991), 266.

18. Highlights of A Fighting History: 60 Years of the Communist Party USA, edited by Philip Bart (International Publishers, 1979), 55; Heyday of American Communism, 324.

19. America before Welfare, 266.

20. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950, by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore (W.W. Norton, 2008), 115.

21. The Unemployed People’s Movement: Leftists, Liberals, and Labor in Georgia, 1929–1941, by James J. Lorence (University of Georgia Press, 2011), 38.

22. Linked Labor Histories, 85.

23. America before Welfare, 266.

24. The Unemployed People’s Movement, 38.

25. Linked Labor Histories, 85.

26. America before Welfare, 266.

27. Linked Labor Histories, 85.

28. America before Welfare, 266.

29. Linked Labor Histories, 84—86.

30. The Unemployed People’s Movement, 35, 36.

31. Linked Labor Histories, 84—86.

32. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 45–47.

33. History of the Communist Party, 250.

34. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 47.

35. Young Worker 9, no. 20 (August 3, 1931): 1.

36. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 47, 48, 52–54.

37. Strike, by Jeremy Brecher (South End Press, 1999), 184, 185.

38. “Red Flame Burning Bright,” 47, 48, 53, 54.

39. Handbook of American Trade-Unions: 1936 Edition, by United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, Estelle May Stewart (United States Government Printing Office, 1936), 15.

40. “A Reevaluation of the Trade Union Unity League, 1929–1934,” by Victor G. Devinatz, Science & Society 71, no. 1 (January 2007): 36, 55.

41. The History of the American Working Class, by Anthony Bimba (International Publishers, 1937), 347.

42. Handbook of American Trade-Unions, 15.

43. Black Unionism in the Industrial South, by Ernest Obadele-Starks (Texas A&M University Press, 2001), 20.

44. The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917–1936, by Mark Solomon (University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 107, 109.

45. History of the American Working Class, 345.

46. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 10: The T.U.E.L., 1925–1929, by Philip S. Foner (International Publishers, 1994), 288.

47. Our Own Time: A History of American Labor and the Working Day, by David R. Roediger & Philip S. Foner (Greenwood Press, 1989), 219.

48. “A Reevaluation,” 37.

49. Handbook of Labor Statistics: 1931 Edition, by Bureau of Labor Statistics (United States Government Printing Office, 1931), 394.

50. Heyday of American Communism, 44.

51. Women and the American Labor Movement, 238.

52. The General Textile Strike of 1934: From Maine to Alabama, by John A. Salmond (University of Missouri Press, 2002), 90.

53. Culture of Misfortune: An Interpretive History of Textile Unionism in the United States, by Clete Daniel (Cornell University Press, 2001), 27.

54. “A Reevaluation,” 42.

55. The Vassar Miscellany News 18, no. 28, February 14, 1934.

56. Biographical Note, Anne Burlak Timpson Papers.

57. Stalin’s Students: The International Lenin School, 1926–1938, by Alastair Kocho-Williams, in Academia.edu (accessed 6/26/14; URL defunct).

58. The Secret World of American Communism, by Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov (Yale University, 1995), 152, 153, 202.

59. “Anne E. Burlak Timpson,” People’s World; “Timpson, Anne Burlak,” American National Biography.

Tony Pecinovsky is the author of Let Them Tremble: Biographical Interventions Marking 100 Years of the Communist Party, USA, which can be purchased from International Publishers.

Images: Burlak walking, The Appendix and KeyWiki; Burlak speaking at rally, ca. 1931–32, Scott Molloy Collection; Election flyer, courtesy of Anne Burlak Timpson Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College (Northampton, Massachusetts); Burlak and Smith Act defendants: Geoffrey Warner White, Daniel Boone Schirmer, Edward Strong, Sidney Lipshires, Michael A. Russo, Anne Burlak Timpson, and Otis Archer Hood, courtesy of Department of Special Collections and University Archives, W. E. B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Join Now

Join Now