Lately, there’s been much discussion among youth about Harry Haywood’s contribution to the Black Belt thesis along with a revival of New Left conceptions of “domestic colony” theories. A lack of clarity and understanding of the CPUSA’s current and historical positions leads to confusion and may divert potential comrades from joining.

It is important therefore that we be clear and open about how to approach the national question for Black Americans and have a full and deep understanding of our Party’s leading role in the struggle against racism in the United States (and internationally). Common misconceptions about what’s called the “African American question” are discussed below.

To first quote Lenin,

Marxism cannot be reconciled with nationalism, be it even of the ‘most just,’ ‘purest,’ most refined and civilized brand. In place of all forms of nationalism, Marxism advances internationalism, the amalgamation of all nations in the higher unity, a unity that is growing before our eyes with every mile of railway line that is built, with every international trust, with every workers’ association that is formed.

The principle of nationality is historically inevitable in bourgeois society and, taking this society into account, the Marxist fully recognizes the historical legitimacy of national movements. But to prevent this recognition from becoming an apologia for nationalism, it must be strictly limited to what is progressive in such movements, in order that this recognition may not lead to bourgeois ideology obscuring proletarian consciousness. (V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 20, p. 34)

What, then, is progressive? Our people’s democratic strivings against oppression, racism, national exclusiveness, discrimination of every sort, inequality in all dimensions, and the championing of culture, identity, and language against all efforts to suppress and diminish them. Marxism stands against the inequality of all racially and nationally oppressed peoples, irrespective of class, but in particular stands for equality, that is, the freedom demands of the working classes of the oppressed peoples.

The following are five misconceptions about the Party’s approach to the national question.

Misconception #1:

The CPUSA’s popular front politics rejected Black self-determination and alienated the Party’s struggle in Black communities.

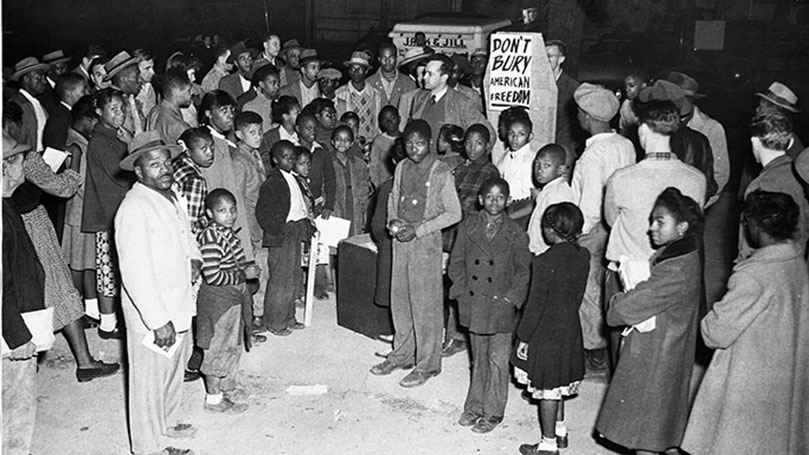

The CPUSA has a long history of Black leadership and has played a leading role in the struggle for full social, political, and economic equality for African Americans and indeed all people of color. Since its founding, the Party has contributed mightily to the struggle against racism and for equality, understanding that the national question, though distinct in its own right, is intimately bound up with the class struggle. This stance, in the Party’s early days, led activists from the African Blood Brotherhood and others to join forces with the Party and led to the creation of organizations like the American Negro Labor Congress and later the Civil Rights Congress. Whether expressed initially as “self-determination” or today as an understanding that fighting racism is central to class unity, this stance considers African American equality as a principled question. To fully be a party of the working class and oppressed peoples, not only in name but in fact, equality must be placed at the center of struggle.

The young Party’s Black leadership, which included Harry Haywood, Otto Huiswod, Cyril Briggs, James R. Ford, and others, developed the “Black Belt Thesis,” also known as the “Negro Nation Thesis,” which determined that Black people in the Deep South constituted an oppressed nation. The “Black Belt” describes a series of majority African American counties extending from Florida north to Maryland. The Party argued that people in these areas had a right to self-determination, that is, to determine their own destiny, up to and including forming a separate state if they so chose. In this regard, Harry Haywood argued in his autobiography Black Bolshevik that African Americans objectively fit the communist movement’s criteria for a nation: a stable community, a common economy, psychological makeup, language, etc.

On the question of Black nationalism and slogans, he said in 1928:

The Garvey movement is dead, I reasoned, but not Black nationalism. Nationalism, which Garvey diverted under the slogan of Back to Africa, was an authentic trend, likely to flare up again in periods of crisis and stress. Such a movement might again fall under the leadership of utopian visionaries who would seek to divert it from the struggle against the main enemy, U.S. imperialism, and on to a reactionary separatist path. The only way such a diversion of the struggle could be forestalled was by presenting a revolutionary alternative to Blacks.

The slogan of “Back to Africa,” I argued, we must counterpose the slogan of “right of self-determination here in the Deep South.” Our slogan for the U.S. Black rebellion therefore must be the “right to self-determination in the South, with full equality throughout the country,” to be won through revolutionary alliance with politically conscious white workers against the common enemy — U.S. imperialism.

This articulation of the Black Belt Thesis and slogan for self-determination in the Deep South remained the CPUSA’s line until the Party was dissolved into the Communist Political Association by Earl Browder’s right opportunism. This occurred as early as 1943 at the end of what’s known as the popular front, the broad people’s alliance formed in the fight against fascism. The popular front and the self-determination policy co-existed for several years prior.

Indeed it was with this policy that the CP in the 1930s and early 1940s achieved its greatest influence in the Black community, prompting some to call it the “party of the Negro people.” Well-known figures such as Richard Wright, Lorraine Hansberry, Canada Lee, and Paul Robeson are associated with this period. In New York City’s Harlem this broad policy helped elect communist leader Benjamin J. Davis to the City Council.

After Browder was expelled and William Z. Foster became the new leader of the Party, the CPUSA re-established itself as a political party and reinstituted the Black Belt Thesis into its program.

Misconception #2:

The CPUSA once again dropped its self-determination line in the 1950s prior to the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s and 1970s. They were incorrect in their analysis of the Black freedom struggle.

The onset of the late 1940s and early 1950s brought with it McCarthyism and a reactionary crackdown on Communists and anyone accused of affiliation with the left. The Party’s leadership was incarcerated, popular front organizations were severed and dismantled, members went underground, and it appeared (mistakenly) that fascism was on its way. During this period, the Party shifted now to the right, then to the left, ultimately adopting more sectarian politics.

As this extreme right reactionary period ebbed in the mid- to late 1950s, the global ramifications of the Sino-Soviet split became quite pronounced, leading to more sectarianism and factionalism. The Party’s leadership in this period (Eugene Dennis, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Henry Winston, James E. Jackson, Benjamin Davis Jr., William L. Patterson, Gus Hall and others) wanted to bring the Party back to relevance after these rough periods of liquidationism, right-opportunism, McCarthyist attacks, and ultra-left sectarianism, all of which damaged it greatly.

This gives context to what happened next — a period of great debate between many Black and other Communist leaders within the Party in the lead-up to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. James E. Jackson, who was a major leader in the Southern Negro Youth Congress and later served as International Secretary and chairperson of the Education Commission and Black Liberation Commission, laid out many arguments against Haywood and the Black Belt Thesis at the 17th CPUSA National Convention, which can be found in his collection of essays titled Revolutionary Tracings in World Politics and Black Liberation.

Jackson wrote in a 1957 report to the Party’s Black Liberation Commission that “Black people in the United States are not constituted as a separate nation. Rather, they have the distinct characteristics of racially distinct people who are a historically determined component part of the United States. This American nation is a historically derived national formation, an amalgam of more or less well differentiated nationalities.” He continued:

At the same time, compounded out of their singular historical experiences — from yesterday’s slavery to today’s aspirations and struggles for complete freedom — the Black people retain special characteristics which manifest themselves (among other ways) in a universal conception and consciousness of their identity as an oppressed people, with a common will to attain a status in the life of the U.S. nation free of all manner of oppression, social ostracism, economic discrimination, political inequality, enforced racial segregation, or cultural retardation. To conclude that Black people in the U.S. are not a nation is not to say that Black liberation is not a national question. It is indeed a national question. The question is, however, a national question of what type, with what distinguishing characteristics, calling for what strategic concept for its solution?

Thus for Jackson, Marxism-Leninism as it applied to the national-colonial question is concerned with the struggles of oppressed nations and nationalities and the relationship of that cause to the liberation of the working class from capitalism in a given country and on a world scale. Lenin’s contribution to Marxism and the national question led to the addition to the famous Manifesto quote: “Workers of the World, Unite!” became “Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples, Unite!” Therefore the national question encompasses not only the nation but also national minorities, national and ethnic groups, national-ethnic minorities, national-communal (religious) groups, and more.

As mentioned earlier, it is vitally important to have a historical understanding of Black people’s development within the United States. Are Black people, over the course of a 400-year-plus period of struggle, developing separately from the rest of the United States? Or have Black people historically developed to be part of the American nation? As Jackson argued,

It is incorrect to focus upon the distinctive “nation-like” features and characteristics of the Black people as the thing of almost exclusive importance to Black liberation in the U.S. Of no less importance in the life as well as the history of the Black people in the U.S. are the integral features and experiences, common history and aspirations of this people to secure their unfettered identification with, and inclusion in, the full rights and privileges of the country. This includes the centrality [emphasis mine] of the Black people’s rightful claim to an equal stake and participation in the country’s total economy — built with more than 350 years of unpaid and underpaid labor, during and since slavery — while being the most exploited, most oppressed, deprived and denied component part of the nation.

If we look at the historical trajectory of the Black freedom movement going into the 1960s, Black people as a whole were (and are still) fighting for full social, political, and economic equality within the United States. If this were not true, would Black people in the Deep South have fought and died for voting rights and against Jim Crow segregation? A separate development for a Black Nation would have been a fight for not just full equality in the South but also for a complete divorce from the United States. This “divorce” has not taken place due to many historical factors, including the Great Migration, the move from the agrarian “Cotton King” plantation South to a more industrialized region, leading to a larger Black working-class contingent within the people as a whole.

Jackson continues:

It is not at all necessary to deny the fact that the Black people in the area of their former majority in the deep South exhibit to one degree or another some aspects of the characteristics common to distinctive nations in order to establish the fact that such partial “nation-like” attributes are not an objective determinative for either the solution or representation of the Black condition in the United States. Such characteristics cannot of themselves mark out the course of development and pathway to Black freedom.

The path of development of the Black people toward individual and “national” equality does not take the route of struggle for liberation in the form of political-geographical sovereignty and statehood. This decisive attribute for nationhood is not present. The Black people in the U.S. historically, now, and most probably for the future, seek solution to their national question in struggle for equality of political, economic, and social status as a special component part of that amalgam of nationalities which historically evolved into the nation — the United States.

Misconception #3:

By saying Black people are not a nation, the CPUSA takes a class reductionist, social democratic position.

Full equality within the context of the national question and specifically identifying Black people as a national minority (due to lacking one or more qualities of a nation) means that, whether Black people constitute a majority population or a numerical minority, they fight for full empowerment on the basis of complete equal rights. This applies to cultural production as well.

Full empowerment includes community control of schools, community control of police, maximum representation in political office, etc. In addition, a key area in the struggle for representation and equality is in the workplace and in wages; that is, the racist wage gap must be addressed. In fact, economic equality is the next and arguably the most important frontier of struggle. This includes not only workers but Black business as well.

This is particularly true for African American women, who face gender, racial, national, and class exploitation.

Thus far from being “class reductionist” the African American struggle is viewed as a special “all class question” involving oppression against an entire people regardless of class.

Further from James E. Jackson:

The Black people suffer a special form of racist oppression. This common experience is national in the sense that all class strata of Black people are subject to a common yoke of oppression and social ostracism, are victims of social, economic, and political inequality. They are racially identified and set apart by racist laws and customs, social existence and by actual ethnic identifications.

If the characteristics of a nation are not the determining factors or indicators of the course of development of Black people, then what is their significance for the Black people’s freedom movement? That there are sizeable areas of the country where the concentration of Blacks in the population is large or a majority is of great importance for the political struggle and economic and cultural development of the Black people. These areas are bases where the Black freedom movement can organize and assert the mass power of its numbers to secure political authority in proportion to Black numerical strength in the population. Such areas of large Black population allow for the continued development of the distinctive in the culture of Black Americans.

What, then, are the objective factors which have operated and continue to operate against the development of the Black people as a nation in the South?

As mentioned earlier, capitalist development affected the stability of the Black community in the Deep South. The overwhelming majority of Black people worked the land as sharecroppers and tenant farmers and were proletarianized due to the demands of mechanization and industrialization that expanded to the South, pushing people to the cities to work in factories and away from the countryside. This process dismantled what may have been considered a “stable community” (one of the qualities of a nation).

Jackson continues:

If objective factors and the line of historical development were operating to enhance the maturation of the national attributes of the Black people and compound their features in nationhood, the Black people would have a separate national destiny whether or not they manifested this consciousness. But the objective factors operating in relation to the Black people in the United States are working not in the direction of national insularity or separate development but in the direction of self-organization within a broad multi-racial coalition of the oppressed and exploited to put an end to the rule of the monopoly successors of the slave power.

Misconception #4:

By not placing Black liberation as a question of an oppressed nation fighting for national-state sovereignty, the CPUSA is diminishing the revolutionary potential for Black people in the U.S.

The CPUSA does not diminish the revolutionary import of Black people’s struggle in the United States. As former Chair Henry Winston noted, “Labor with a white skin and labor with a Black skin could not be free unless the special demands of the triply-oppressed Black people were put at the center of the struggle for progress and socialism.” Furthermore, Marxism insists that socialism will never be achieved unless the special equality demands of Black people are addressed, not in the distant future but in the immediate present. “The struggle of the Black people for the democratic goals of political, economic and social equality feeds into the general stream of the historic working class cause, of which the Black workers are a decisive component,” said Jackson.

Championing the struggle for equality is central to both the class struggle and the struggle for democracy and therefore social revolution in this country.

As evidenced from the fight against slavery and the War between the States, through the Civil Rights struggle, the sub-prime swindle that precipitated the Great Recession until today’s uprisings, racism, and anti-black racism in particular, is the Achilles’ heel of capitalism.

Misconception #5:

Dropping the demand for self-determination changed the Party’s relationship to the Black community in a fundamental way and led to a shift to the right.

While true that the CPUSA no longer upheld the Black Belt Thesis after 1958, it has always upheld and fought for the independence and right of African Americans to determine their own destiny. In this sense the Black freedom movement is self-determining, not so much as a slogan but in real life.

Jackson puts it this way:

It seems to me that such relevance as the general principle of self-determination has to the reality of the status and outlook for the Black people’s struggle in the United States can be expressed as:

The right of a people — irrespective of their level of, or direction of, development as a national entity — to act in concert, or in alliance with fraternal classes and peoples, under the direction of their own leadership, after the fashion they may choose, in pursuance of their own goal of freedom as they so conceive and construe it to be at any given moment, is an inalienable democratic right of that people which can neither be ceded or withdrawn by any other power. In this sense, the right to self-determination is to the national community what the right to freedom of conscience and freedom of political choice is to the individual.

In terms of damaging our Party’s relationship to the Black community, this is just demonstrably false. Since dropping the slogan in 1958, the Party was still organizing in Black communities and was heavily involved in the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement from its earliest days. Young Black members who got involved with the Du Bois Clubs were also leaders in SNCC, CORE, and other civil rights organizations of the period.

African American communists remained active in the labor movement and continued to function in various capacities and African American–led formations like CBTU along with union Black caucuses.

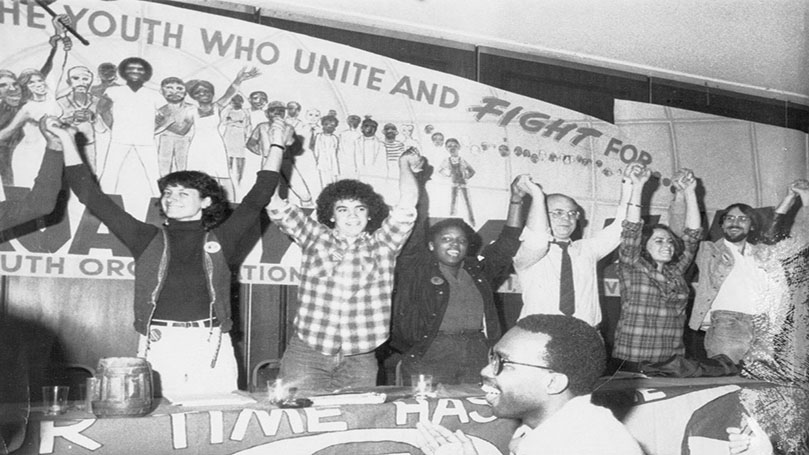

Black Party leaders helped form the Young Workers Liberation League, which was created around the same time as the National United Committees to Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners came into existence, led by Charlene Mitchell and Louise Thompson Patterson. The committees that helped grant Angela’s freedom then worked to free Joanne Little, and these organizers ultimately formed the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression. The Alliance waged long and successful struggles, including winning the freedom of Rev. Ben Chavis and the Wilmington Ten.

Around the same period, Henry Winston was among the first to call for the freedom of Nelson Mandela and comprehensive mandatory sanctions against South Africa. Winston led the call to form the National Anti-Imperialist Movement in Solidarity with African Liberation (NAIMSAL).

The CPUSA was also a founding member of the Black Radical Congress and supported its efforts in many cities across the country.

The decline in anti-communism after the collapse of the Soviet Union created political space for CP members to become active in mass organizations, civil rights organizations, and trade unions. And there African American communists remained at the local level fighting on various fronts for jobs, housing, and health care and against police repression and murder.

In recent years, from the Ferguson uprising to the Cleveland protests of the murder of Tamir Rice, the NY protests against the strangling of Eric Garner, or the nationwide uprising against the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, CP members — Black, white, Asian, and Latino — have been a present and visible force.

While the Party still has a strong contingent in the Black community, it has been weakened at various moments in its history, and our work is not beyond criticism.

The heightened attack on African Americans by the fascist and Republican right aimed at disempowering our community by means of voter suppression along with police murders has led to the movement for Black lives and the largest and most diverse anti-racist movement in the U.S.

In these circumstances our reformed African American Equality Commission will lend a sharper and more targeted focus on Black neighborhoods and issues. We invite readers to join us in our work.

Images: BLM protest, Peg Hunter (CC BY-NC 2.0); March for Scottsboro Nine, National Negro Congress protest, Civil Rights Congress Denounces DC Police Raid on Progressives, Young Workers Liberation League meeting (CPUSA archives).

Join Now

Join Now