Since Marx and Lenin, the world market that they studied during their lifetimes has grown and changed immeasurably. In tandem with the establishment of the world market, Marx writes that “the bourgeoisie developed, increased its capital, and pushed into the background every class handed down from the Middle Ages” and “in place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations.”

This interdependence that Marx describes, though perhaps shocking at the time, was a mere nascent form of its existence today. This is no better illustrated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Whereas it took a ship months to reach Italy with the England-sourced plague in the Middle Ages, the coronavirus spread between hemispheres in mere hours by plane. Over half a millennium ago, towns were blockaded off from other markets in an attempt to stop the spread of disease. In the second decade of the 21st century, such blockades were functionally impossible. Even if countries like New Zealand prevented all travel at their airports for passengers, the movement of goods and services could not cease between the island nation and other markets.

In New York and elsewhere, members of the Asian community were subjected to racist attacks. Despite donning masks in solidarity with their neighbors, months before the first mask guidance came from the city government, they were seen as the primary vectors of the disease. This was not helped by the president at the time, Donald Trump, who stoked this racist violence by calling the coronavirus the “Wuhan Flu” and “China Virus.”

Yet when the masks arrived, they were stamped as made in China. The tests used to detect the coronavirus were likewise made in China. Most of the ventilators were made in China.

These circumstances were emblematic both of the increasing interdependence of the world market as well as the social and national chauvinism that Marx, Engels, and Lenin righteously railed against.

Chauvinism: A tool to divide

Marx himself was stateless for most of his life — nearly 40 years — while Engels, guided by Mary and Lizzie Burns, learned much of his politics from the immigrant Irish workers that his father employed in British factories. Lenin, too, was exiled from his country of birth for some years. Their opposition to national and social chauvinism, informed by their personal experiences as well as their study, were among their foremost political objections.

While writing on the importation of Irish labor into the British market, Marx charged the English bourgeoisie with viewing immigrant labor as a way to lower the “wages and material and moral position” of the working class. But even more important to the capitalists, he said in his letter to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, was that this created “a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians.”

“The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the “poor whites” to the Negroes in the former slave states of the U.S.A. …

“This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.”

Hundreds of years after Marx put pen to paper, this antagonism between workers is still utilized by the ruling class to divide and weaken the working class. Like racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination, national chauvinism and anti-migrant bias is used as a violent wedge to distract from the bigger game afoot.

Xenophobia returned to the English-speaking world after decades of neoliberal globalization, a process that emerged in the decline and collapse of the Soviet Union and expanded capital’s geography like never before. Popular capitalist culture stressed a new “multicultural” identity that accompanied the expanding world market.

In the backlash to neoliberal globalization, the target was initially economic in scope — the anti-globalization and anti-sweatshop movements of the late 1990s and early 2000s took advantage of this new “globalized” vision of a “multicultural” humanity to push progressive economic policies. But in the wake of 9/11, the extreme-right began inverting this opposition to neoliberal economic policies, putting the target instead on the back of the foreign other — the worker who supposedly takes jobs, justifies layoffs, or poses a threat to one’s physical safety.

While anti-migrant anxieties were present in the United Kingdom in the era of decolonization, as those from its prior colonies relocated there, these nativist trends took on a whole new tenor decades later in the form of a backlash against the European Union. While British capital bemoaned the regulatory system, the story spread among workers was that those outside the U.K. were coming to steal their jobs and spread crime. The result was Britain’s exit from the European Union, and a 50% reduction in the country’s GDP growth. British-born workers had been sold the lie that workers from elsewhere were to blame for the decline in their circumstances and privatization. However, since 2016, the quality of life for workers in the United Kingdom has continued to decline.

MAGA’s double lie

MAGA’s approach to the question can be summarized under two fronts. The first is the lie that unauthorized workers are more likely to commit crimes and consume public resources, which is easily disproved. Unauthorized workers are far less likely than native-born workers to commit crimes, precisely because of the threat of deportation. Through their labor, they contribute around $100 billion dollars in tax money each year to the United States, while mostly remaining ineligible for social security, medicaid, unemployment, workers compensation, and disability benefits. Many also voluntarily refrain from participation in social programs they are eligible for, due to concerns that their information could be shared with other government agencies.

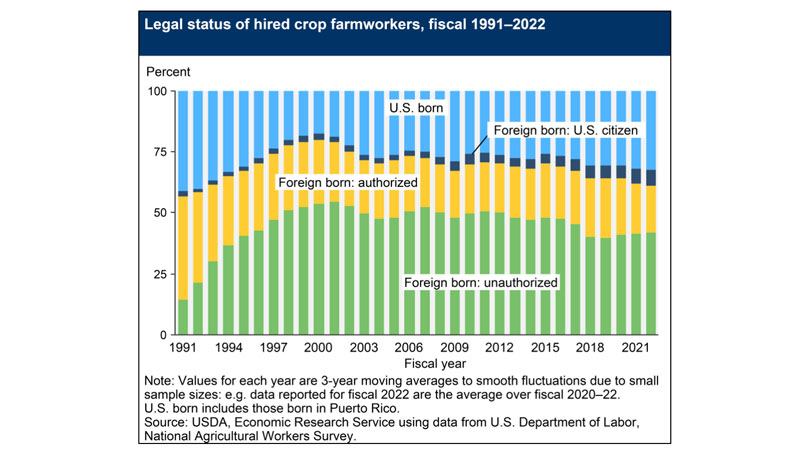

That this front is so easily disproved by basic facts seems to indicate that its foundation is largely racism and national chauvinism. Low-paid migrant workers engaged in types of labor that native-born workers generally avoid are also the least likely to be disposed of and deported. Indeed, more than half of all farmworkers and construction workers are foreign-born. Stoking hatred against them serves to further isolate them from the rest of the U.S. working class, facilitating their intensified exploitation.

It is clear that “mass deportations” of these workers would effectively destroy major industries in the United States.

The other front against workers is a bit more on-the-nose, claiming that “indentured servants” are being imported to replace well-paid workers with U.S. citizenship or permanent residency.

There is a dual implication that these skilled workers are “indentured servants” because their work authorization is linked to their employer and they are paid less than native-born workers, but also that they are taking something away from workers with U.S. citizenship. This error is exemplified by the recent discussions regarding H-1B visa workers, where even social democrat Bernie Sanders and labor leaders like the Teamsters’ Sean O’Brien have fallen into the right’s ideological trap. While hiding their chauvinism with crocodile tears for “low-paid indentured servants from abroad” or “exploit[ed] foreign workers,” they say that H-1B visa holders “replace good-paying American jobs.” Workers, by definition, cannot “replace” jobs.

Economists who study wage differentials between foreign-born and U.S.-born workers fail to account for the fact that foreign-born workers are not the only super-exploited section of the working class. Many of these foreign-born workers are also people of color and women, both sections of the working class that, even if native-born, are subjected to lower wages in order to increase profits, divide the workforce, and push down wages overall both within and across different sections of the economy. This is especially true when it comes to prison labor or certain types of labor mainly relegated to women.

The answer to what Claudia Jones described as the “triple oppression” of such labor (female, non-white, and foreign-born) is not to further oppress women, people of color, and migrants by ejecting them from waged labor in the United States — though this is certainly the goal of the MAGA right with its attacks on abortion, affirmative action, and migrant rights. It is, rather, to attack these oppressions head-on as fundamental threats to all workers and organize for equal representation, wages, rights, and benefits for all — regardless of gender, race, nationality, or work authorization status.

One working class in a world market

In reality, there is one working class and, as the movement of capital across borders proves every day, jobs themselves hold no nationality, race, or gender. There is no such thing as a “women’s job” or a “Black job” or “the white working class.” Additionally, there are no “American jobs,” just as there is no “American working class.” There are simply workers and jobs located in the United States that are in economic and social intercourse with an increasingly interconnected world market.

And, as Marx foresees, the working class becomes more and more intermingled under these conditions. Rural workers move to cities and vice versa. Workers cross borders, sometimes for temporary reasons. Technology aids communication and collaboration. It is not unusual for multinational companies to employ digital teams that stretch timezones so as to lengthen the working day in ways Marx could have never imagined. Workers buy items online from warehouses across the planet that arrive as quickly to their doorstep as they would from the next city. Culture, news, art, and cuisine ricochet around the planet almost instantaneously. The consciousness that there is only one working class is increasingly heightened and consolidated under such conditions.

The break between the Second and Third International was on the issue of war. While “workers of the world, unite!” had been the official slogan of the world socialist movement, when the chips were down, the parties who claimed to represent the working class fell prey to bourgeois nationalism. Horrified, and armed with his analysis of imperialism, Lenin denounced this capitulation in the strongest possible terms.

Likewise, today we stand on the precipice of something terrifying. Another Trump presidency looms, with foreign policy plans akin to arch-imperialist William McKinley’s administration. He bloviates about seizing the Panama Canal, Greenland, and even Canada. He is planning to introduce tariffs at rates not seen for hundreds of years. But Trump also claims that he was elected because of his “America First” promises, the most important being mass deportations. What does such forced displacement have to do with his imperial ambitions?

A grand distraction

The tariffs will raise prices. Expanding capacity for conquest, incarceration, and repression will likewise be expensive. As this unfolds, there will also be intense blows to our social safety net via Project 2025, with rolling privatization of public services. Pollution will be unleashed. The only way that the ruling class can distract us from their culpability in these circumstances is to blame it on others — in this case, workers with different nationalities. Whether working in the United States or abroad, they are the enemy that Trump will ultimately present as a scapegoat for monopoly interests.

The entire “debate” around workers on an H-1B visa — a mere 580,000 or so out of the 168.5 million workers in the United States — is a red herring: smoke and mirrors meant to distract from the larger issues at hand, while shoring up bourgeois nationalism. All workers are entitled to dignified housing, healthcare, wages, and working conditions. Being drawn into whether or not ~0.3% of workers are detrimental to our living conditions is obviously a waste of time when the Trump-controlled Supreme Court is prepared to hear cases on whether or not the National Labor Relations Act is constitutional.

Internationalism is at the core of our tradition and our work is stronger when it is at the heart of all we do. Take the Russian Revolution, for example, or the Cuban medical brigades. Look to the end of apartheid in South Africa, or to the freeing of Angela Davis in the United States. Look at the struggle for justice in Palestine. To move through the next era of MAGA policies, we will need to reach for and hold fast to our greatest weapon — collectivity. That collective action must be built on the understanding that workers are workers wherever we are, and that all of us have equal claim to the value we create.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: Farmworkers pick strawberries at Lewis Taylor Farms by U.S. Department of Agriculture (public domain) / office workers (pxhere.com) / A worker looks closely as containers are unloaded in Qingdao Port, Shandong province by China Daily; Workers operating heavy machinery in the power loom house at Early Blanket Mill in Witney, Oxfordshire, in 1898 (Historic England Archive); Legal status of hired crop farmworkers, fiscal 1991–2022 by Marcelo Castillo / USDA (public domain); A cargo plane from China arrives in Chicago with surgical masks gowns in response to COVID-19

Join Now

Join Now