This article is being reprinted from Political Affairs in celebration of Women’s History Month. It was first published in April 2010.

From its very outset, the struggle for women’s liberation has had deep connections to the development of the socialist movement. The utopian socialist Charles Fourier said famously that a society was judged by its treatment of women. The oppression of women in both work and in the home and the hypocrisy of bourgeois morality were dealt with by Marx and Engels over and over again in their works, not as something separate from the class struggle and the exploitation of the working class by capitalists but integral to it.

In a number of European countries, Marxist socialist parties, in the tradition of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), advocated women’s suffrage and women’s rights when liberal and even self-styled radical parties avoided the issue for fear of losing both their capitalist financial backers and male votes.

Women activists in the United States were a part of the socialist movement and organizations like the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) before women gained the right to vote, although the leaders of the Socialist Party of America (SPA) were no more militant or focused in their support for women’s suffrage and women’s rights than they were in the support for the civil rights and larger social economic liberation of the African American people.

With the formation of the Communist Party USA and its development after 1919, militant women, like militant African Americans of both genders, were drawn to the CPUSA in far greater numbers than the declining Socialist Party or other groups on the left. These included very well-known activists like IWW leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and labor radical Mother Bloor.

Flynn, for whom the martyred IWW people’s singer Joe Hill had written the song “Rebel Girl,” was to become the most famous CPUSA woman leader of the interwar period and would become a Cold War political prisoner in the 1950s. She would end her long and distinguished life as chair of the CPUSA in the early 1960s after her release from prison.

Her life can be contrasted with that of Margaret Sanger, a socialist champion of women’s reproductive rights before and during World War I. Both faced state repression. Sanger, though, left the socialist movement and became a founder of Planned Parenthood in the postwar era. While she remained a progressive, she found herself courting business interests and hobnobbing with overt racists, neo-Malthusian reactionaries, and more covert racist eugenicists whose support for birth control was rooted in a desire to limit working class and minority populations.

Women like the West Indian-born Harlem activist Claudia Jones became, in the 1930s, important grassroots leaders of the CPUSA youth organizations and later the CPUSA itself. Mexican-American activist Emma Tenayuca led striking agricultural workers and was called “La Pasionaria de Texas” in late 1930s San Antonio.

Although male chauvinism certainly existed in the CPUSA, the Communists were really the only political party which used the concept of male chauvinism in any way and sought to combat it. In this sense, it was continuing to develop a concept rooted in both the pre-World War I socialist and feminist movements. At times, these movements were allies, although often divided over what feminists saw as the Socialist Party leadership’s sellout of women’s rights and what male socialists’ saw as feminists’ “bourgeois” orientation, struggling for political rights and entry into elite positions at the expense of the larger working class.

Although male chauvinism certainly existed in the CPUSA, the Communists were really the only political party which used the concept of male chauvinism in any way and sought to combat it. In this sense, it was continuing to develop a concept rooted in both the pre-World War I socialist and feminist movements. At times, these movements were allies, although often divided over what feminists saw as the Socialist Party leadership’s sellout of women’s rights and what male socialists’ saw as feminists’ “bourgeois” orientation, struggling for political rights and entry into elite positions at the expense of the larger working class.

The CPUSA actively bridged these differences, not with complete success by any means but to a greater degree than any other group. Within the women’s labor movement, the number of militant CPUSA-affiliated women who became union leaders was, from my readings, greater in percentage terms than the number of CPUSA-affiliated men, although this is very difficult to quantify since the deforming effects of anti-communist policy meant that CPUSA affiliations were often unacknowledged.

For example, in the rightly distinguished documentary, Union Maids, the stories of three 1930s women labor activists are told without, given the crippling effects of postwar McCarthyite repression, once mentioning that all three were CPUSA activists. In reality, they would have to have been Communists, given the support system they relied on to continue their struggles. In the documentary, all three women are asked to say what socialism meant and means to them. While this is done well, understanding the women and their conceptions of women’s rights, racism, sexism, and socialism is significantly reduced without any treatment of their CPUSA context.

Major histories of women in and of the CPUSA have yet to be written, just as systems of national health care, full employment policies, de jure and de facto gender equality, have yet to be established in the U.S. But there is much that we can say about the Communist contribution to gender equality and the negative effects of both anti-communist ideology and policy in undermining the struggle for women’s rights as it has undermined all people’s struggles.

Even before World War II, Communist-affiliated trade union women in the Communist-led United Electrical Workers union (UE) established the first contract in which women workers were given a larger hourly increase than men in an attempt to make up for long-term gender inequality, an early practical example of what would decades later be called affirmative action.

As the labor movement expanded and millions of new women workers were drawn into war work in the 1940s, Communist-affiliated women in the industrial unions especially fought to protect women workers from on-the-job discrimination and also to support federal legislation to provide public daycare services—legislation which was the first of its kind but which conservative coalition opposition in Congress defunded to the point that it became little more than tokenism.

CPUSA-affiliated women who were the wives of military personnel also organized around military bases in the U.S. (the great majority of the 15 million who served in the military did not see service, much less action abroad) to both fight against the effects of military segregation and also to oppose the racist violence that this segregation helped to engender, especially on Southern bases where legal segregation was in effect.

CPUSA-affiliated women continued to play a leading role in struggles for labor’s rights, against racism, and for peace during the Cold War era—in some respects an even larger role, given the success of the purges and blacklists and anti-Bill of Rights legislation frightening so many away from exercising their rights to freedom of speech, assembly, and association.

Communist-affiliated women played an important role in the formation of Women’s Strike for Peace in the 1960s and the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW) in the 1970s, even though institutional McCarthyism created in these and other organizations a kind of “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

Earlier women like Mary Licht, whom I had the privilege of knowing through the CPUSA’s History Commission and who had participated in the South at great risk in the defense of the Scottsboro Nine, dedicated the rest of their lives to the defense and development of the CPUSA. Women like Dorothy Burnham, African American scholar and intellectual whom I had and have the pleasure of knowing in the CPUSA, played important leadership roles.

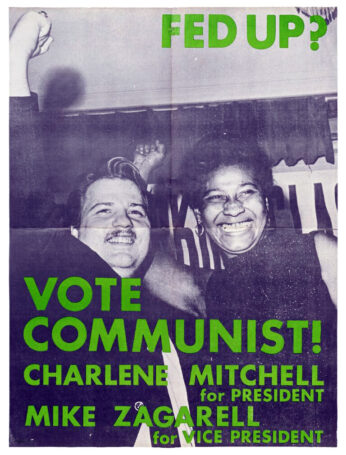

In 1968, when the CPUSA, after nearly three decades of repression and what would be considered internationally as persecution, ran its first presidential campaign since 1940, Charlene Mitchell was the candidate at a time when the presidential candidate of any “third party,” left or right, was virtually unknown. She was the first Black woman to run for president of the United States.

In 1968, when the CPUSA, after nearly three decades of repression and what would be considered internationally as persecution, ran its first presidential campaign since 1940, Charlene Mitchell was the candidate at a time when the presidential candidate of any “third party,” left or right, was virtually unknown. She was the first Black woman to run for president of the United States.

The influence of political parties and social movements exists on many levels. Betty Friedan, for example, came from a middle-class Jewish American family in Illinois, attended an elite women’s college during World War II, and then did graduate work at Berkeley. There she became involved with a variety of political struggles, some of which included Communist Party activists, and she then went to work for the left-labor Federated Press. This media outlet attempted to provide for working-class media what the Associated Press did for capitalist media.

Friedan later wrote for the UE News and supported the Progressive Party in 1948. She grew up politically in a left movement and culture in which the CPUSA played the leading role. Although the postwar repression ended her career as a left-labor journalist, she continued to try to write for women’s publications as she settled uncomfortably into the role of a suburban housewife.

Issues of male chauvinism inside the CPUSA were revived during the early Cold War era and discussed in party clubs and forums as the repression sought to build what French Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre called a “ring of fire” between Communists and their fellow citizens. Friedan, through her early 1960s work The Feminine Mystique, played an essential role in articulating what in socialist and later Communist circles was called “the women question.” She always went to great lengths to hide or simply ignore her past as she became a celebrity, and aimed her feminism initially at college-educated women frustrated with their lives as housewives whose labor was both unpaid and undervalued.

But one can find in her work an analysis of and resistance to ideologies of oppression that was a foundation of the Communist movement in the period in which she came of age politically. One can also find in her later work as a founder of the National Organization for Women (NOW) an emphasis on building broad, inclusive organizations and acting politically both inside and outside normal channels. She advocated lobbying for changes in the law, organizing mass protests to advance such changes, and preparing the movement for future advances. This kind of strategic and tactical outlook also characterized the Communist Party and the larger left movement which was the leading force in her youth.

The relationship between Communists and feminists in the 1950s and ’60s was complex, usually cooperative, and sometimes contradictory, as it had been much earlier between Socialists and feminists in the pre-World War I era. The ideological straitjacket that Cold War politics sought to trap all Americans in made it difficult to acknowledge and understand those relationships, but understanding them is very important if both the successes and failures of the past are to serve as guides to contemporary struggles.

Angela Davis took a very different path than Betty Friedan. An African American scholar, intellectual, and activist, Davis grew up in the postwar left and CPUSA political culture from which Friedan withdrew. She became a CPUSA member and supporter of the Black Panther Party, a teacher of philosophy, and a political prisoner whose acquittal in the early 1970s was itself a victory over a generation of political repression.

She also worked as an activist against racist and political repression, for comprehensive reform of the criminal justice system, and for the full inclusion of African Americans and all other minority peoples in a pluralistic democratic American culture. Although Davis later left the CPUSA, it was in a non-polemical way and, unlike some others, she never lent her name to anti-Communist activities and remains a friend of the party.

Davis became an international figure through her membership and leadership in the CPUSA for a generation. Her writings here and abroad reached large numbers with their eloquent portrayal of struggles in the U.S. against racism, male chauvinism, imperialism, mass incarceration, and war. She also reflected the CPUSA’s internationalist outlook by relating those struggles with people’s movements throughout the world.

One could go on and on listing the accomplishments of CPUSA and Communist movement-affiliated women to people’s movements and struggles, both the famous, like Anne Braden and Meridel LeSeuer, and the many less well-known activists fighting for tenants’ rights and rent control, campaigning to get city councils to pass resolutions for single-payer health insurance, the establishment of nuclear-free zones and nuclear disarmament, the transfer of billions from the military budget to people’s needs and more.

Although gender integration has advanced greatly in the U.S. and through many organizations, so much remains to be done. But the long-term struggles and achievements of Communist women in the supportive atmosphere the CPUSA established are indispensable contributions to the success of the campaigns to advance women’s liberation in both the present and the future.

Images: People’s World and CPUSA Archives; Emma Tenayuca, “La Pasionaria de Texas” (CPUSA Archives); Charlene Mitchell campaign poster (CPUSA Archives)

Join Now

Join Now