The spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) earns its name by the yellow spots found on its carapace (top). The underside (not visible) or plastron of this spotted turtle is flat. It indicates that this is a female. Males have a concave plastron.

It was a number of bluebird enthusiasts who stumbled on the spotted turtle in June of 2024. It turned out to be a very significant find at the Gunntown Passive Park and Nature Preserve, Naugatuck, Connecticut.

Spotted turtles are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is now a species of concern in Connecticut. It was a volunteer steward of the local Nature Preserve, an immigrant, who initially discovered the same, exact turtle at the bottom of a stream, in May of 2016.

The excitement was palpable. The nature preserve was “working.” It fit the working definition of a preserve. Wildlife came first.

It almost didn’t happen. Here’s the back story.

In 1995, there were three discernible groups vying for the town-owned land where the above action took place. They all saw a different use-value in the land.

The utility of a thing makes it a use value. A commodity, such as iron, corn, or a diamond, is therefore, so far as it is a material thing, a use value, something useful. This property of a commodity is independent of the amount of labour required to appropriate its useful qualities. — Karl Marx

A coterie of sports advocates, centered mainly in the town’s public works/park and recreation departments, wanted the land used for a sports center. Multiple sports fields, a running track, basketball courts, and other team sports areas were the objectives. Construction contracts, commodities, and money would flow. Administrators would then be able to sell their skills, their abilities or labor power, to other, “richer” towns for a higher salary.

A grassroots group, mainly veterans of the 1960s/70s movements, high school girl scouts, and immigrants wanted the land used for passive (no hard surfaces) recreation and a nature preserve. While not opposed to sports areas, they pointed out that there was already more than a dozen such active (hard surfaces) open spaces in town. They issued a petition and garnered more than a thousand signatures for their cause.

Spotted Turtle – Clemmys guttata

The third force centered around a mayor who was elected as an independent. He could not reasonably run again as a Democrat as he did a jail time in the 1980s for taking bribes while in office previously. He also had a reputation as a tyrant as the second group would soon discover. He would have fit nicely in the 1930s as one of those appointed, fascist mayors in Italy. He specialized in threats.

This mayor saw more than use-value in the land. He put forward a proposal to sell back the land to the local bank who ended up with its ownership in the early 1990s. The land was originally purchased for $400,000. It would put the monetized land back on the market for sale. Now it would be a commodity. It would now have exchange value.

Exchange values [are] use values that fetch a price on the market.

Paul Burkett — author of Marx and Nature: A Red and Green Perspective and other books

When the mayor saw the support for the grassroots group, he made his move. The mayor approached the bank with his proposal which he purported would recoup taxpayer’s money. This would be part and parcel of his appeal to the electorate. He claimed the land was just a “swamp”.

The mayor would resolve, in Marxist terms, the contradictory tension between use-value and exchange-value. In this scenario, value would be resolved in favor of the latter. And, he thought, that would also ingratiate him with taxpayers.

Of course, the mayor miscalculated the grassroots, door-to-door work of the burgeoning environmental movement. Money was raised. This diverse movement was building political power. They wanted that swamp and other, diverse wetlands and meadows for wildlife and passive recreation. The land also fed the water table that helped recharge wells in the area and, further, prevented flooding.

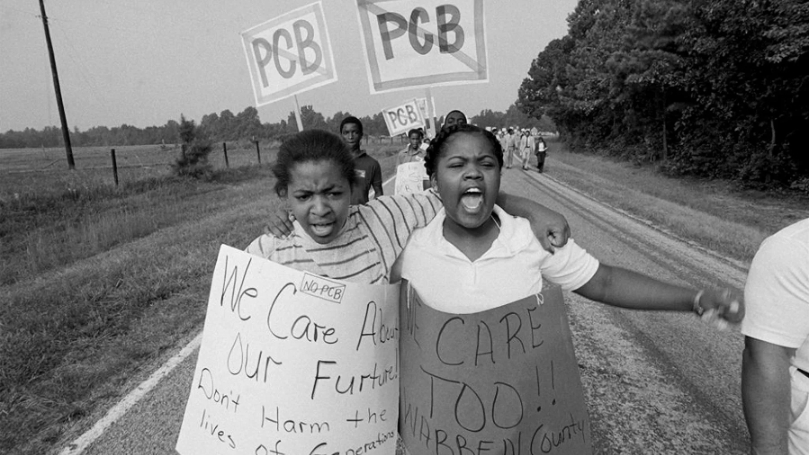

Environmental protesters on the road to the Warren County Landfill in Afton, North Carolina, in September 1982.

In new millennial terms, the land was a climate change mitigator. Those 1,000 signatures represented many taxpayers’s wish to retain those ecosystem services.

True to form, the mayor issued threats aimed at the grassroots leaders. They knew expansion of their coalition was a necessity, but how?

The “greens” formed a network with other environmental groups e.g. river groups. The latter knew the importance of the wetlands, and the stream running through it, for the local river system. But would that be enough?

When it was pointed out that an important story from the revolutionary period of the 1770s/80s occurred on the land, the greens jumped on it. The local historical society was brought on board. The regional labor council was appealed to with the potential for green jobs with the passive/nature preserve proposal. The use-value of the land would be enhanced.

It started to come together. The alliance of greens, history buffs, and labor formed a cultural/environmental alliance. They sponsored a free play featuring the revolutionary roles of a woman, young people, and a slave. Hundreds of school children experienced outdoor theater on the land.

The combination of grassroots organizing and years of revolutionary patience worked. The monetized, phony reelection plan of the mayor’s collapsed. He would never again run for office. He moved on as the paid advisor to the next mayor, a Republican.

The land was won as a passive park and nature preserve. The contradiction was resolved in favor of its natural use-value.

Back to the spotted turtle. Given the early June appearance of this female, egg laying had to be on the reptile’s agenda. She had the wetlands, meadows, and passive land to safely carry out her life cycle.

The land had another, important story to tell.

Images: Youth standing up for their rights by Center for Progressive Reform; VOA in spring by Patrick Coin (Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic Deed);

Turtle by Len Yannielli; Protesters on the road to the Warren County Landfill in Afton, NC, in September 1982 by UNC libraries;

Join Now

Join Now