In some ways the life of centenarian Al Marder reads like a serial thriller with plenty of comedy and tragedy, defeats, and victories.

As a teenager, he would sneak out of his parents’ house in a working-class neighborhood of New Haven, Connecticut, early in the morning to meet his good friend Sid Taylor, push the family car down the road before starting it so as not to waken his parents. They would distribute fliers and Daily Workers to workers arriving and leaving plant gates at Sargent and Co., after which they would reverse course and Al would sneak back into the house. Years later his mother revealed that his parents were in fact aware of his goings-on.

What’s remarkable about Al Marder is not so much that he just passed his 100th birthday this January but that he constantly raises urgency in opposing war and injustice, an urgency that is undiminished in the nearly 50 years I have known him. What’s remarkable is that he combines his deep historical analysis of current events with demands for action to address them. What’s remarkable is that he doesn’t hesitate to press comrades up and down the ladder to act for peace and racial justice, to reach for unity with the broad people’s movements.

Al Marder entered the fight for justice and peace when he was fourteen years old, the height of the Great Depression. He saw families being evicted, his own included, and Communists moving their furniture back. He wasn’t alone. The nation was demanding peace. Workers were struggling for their rights and moving unionization to the fore.

Al Marder entered the fight for justice and peace when he was fourteen years old, the height of the Great Depression. He saw families being evicted, his own included, and Communists moving their furniture back. He wasn’t alone. The nation was demanding peace. Workers were struggling for their rights and moving unionization to the fore.

Peace, he has said, was a central demand of the Communist Party in the 1930s.

He became an organizer for and then at age 16 headed the Young Communist League. Al began to connect the anti-Semitism that his family, Jewish immigrants from Ukraine, experienced with the prevalent anti-Black racism. He found that Communists modeled equal treatment of everyone.

At the New Haven Peoples Center, Al found his milieu. This community center had been bought by immigrant, socialist-oriented Jewish tradesmen for their own families and the broader community. There Al participated in creating the first integrated theater group, the Unity Players, which among others performed Plant in the Sun in a tournament at the Yale Drama School, which they won, and in union halls throughout Connecticut.

Through the Peoples Center Al also managed the Young Communist baseball team, the Redwings, the first integrated team in New Haven, built campaigns to integrate the city’s bus drivers’ union, and with other young Communists organized an evening college for workers through the New Haven Teachers College. Eventually Al would become the president of the nonprofit that runs the Peoples Center.

Al tells a scary story that as a U.S. soldier during World War II he was alone on a scouting mission in Austria when he heard the rumble of tanks and trucks he thought were German. He dove into a ditch alongside the road to hide, frightened of being captured. The convoy stopped by him, motors running, but the soldiers who exited the vehicles and spotted him weren’t speaking German. To his surprise they spoke Russian. Al was perhaps the first GI to experience greeting and being warmly greeted by his Soviet counterparts coming from the east to liberate Austria.

On other occasions in the European theater Al demanded that Black soldiers be able to sit with their white counterparts in movie theaters.

As German town after town was liberated by allied troops, Al was assigned to seek out non-Nazis to govern those cities. He did and to his surprise found anti-Nazis living among the population, often communists who had survived the war.

After World War II ended, Al returned to union organizing in Connecticut and to study at the University of Connecticut, organizing his fellow students along the way. He was hopeful that the founding of the United Nations would bring about peace and an end to colonialism.

But after the war the U.S. turned its big guns on its former ally the Soviet Union and with McCarthyism attacked the progressive movements at home.

In 1954, one of eight charged in the Smith Act witch hunts in Connecticut for thinking communist thoughts, Al had to leave his family and go underground. Eventually caught, he was tried and acquitted, but not without serious consequences to many lives.

In the 1970s and 1980s Al became a leader in the peace movement as the president of the U.S. Peace Council and vice president of the World Peace Council, positions he still actively holds.

A prime organizer of the anti-apartheid struggle in Connecticut, Marder helped create and lead the city of New Haven Peace Commission in 1988 and today continues as an active member. Among other things, the Commission arranged for annual peace marches among city high school students, annually planted trees, and laid plaques in public parks and on school and library grounds on the International Day of Peace, and created a UN-recognized Peace Garden.

The Peace Commission introduced resolutions into the New Haven city council, the Board of Alders, calling for abolition of nuclear weapons and moving money from war spending to human needs. On three occasions the resolutions became ballot initiatives that won overwhelming approval from the city’s voters.

As a result of these activities New Haven was invited to join the UN-sponsored International Association of Peace Messenger Cities, of which Al Marder was president for 12 years, the only non-mayor to hold that position.

Urged in 1987 by African American school board president, minister and friend Rev. Edwin Edmonds, Al founded the Connecticut Amistad Committee, Inc. in the spirit of the original 1839 Amistad Committee, the first integrated abolitionist organization.

Urged in 1987 by African American school board president, minister and friend Rev. Edwin Edmonds, Al founded the Connecticut Amistad Committee, Inc. in the spirit of the original 1839 Amistad Committee, the first integrated abolitionist organization.

Under Al’s tutelage the contemporary Committee lifted the story of the Mende people captured by Spain who revolted on the ship taking them to slavery and ended up in New Haven. Their fight for freedom, a victory stamped by a Supreme Court decision, was a shot in the arm for the abolitionist movement. With Al’s concerted efforts a statue to Singbe Pieh, leader of the revolt, stands proudly in front of New Haven City Hall.

The 1997 Steven Spielberg movie Amistad dramatizes these events, while a replica of the Amistad ship has sailed the story around the world.

Last October the Connecticut Amistad Committee held a gala dinner celebrating the legacy of Al Marder with friends and accolades from around the world.

With his amazing memory, wry sense of humor, and easy laugh, Al is a great storyteller, attending to detail and drawing basic lessons.

The CPUSA celebrates Al Marder’s 100 years, all that he has accomplished and what’s still to come.

A number of biographical stories with more about Al Marder appear here:

“Interview with Al Marder,” Marxism-Leninism Today.

“New Haven’s Al Marder, Nearly 98, Still Fighting for Peace and Justice,” New Haven Register.

“Happy 100th Birthday, Al Marder,” Arts Council of Greater New Haven.

“Al Marder: A Life of Conviction,” Connecticut Explored.

“Lutar contra o imperialism por dentro do império,” Revista princípios.

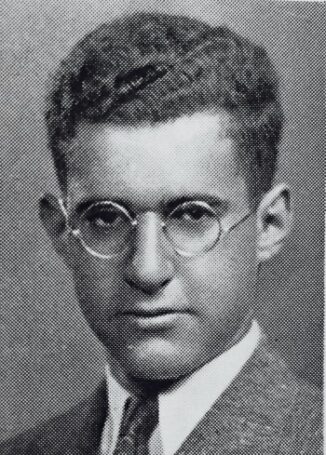

Images: Anti-war protest, photo courtesy the author; Al in high school; with friends at the New Haven Peace Commission windmills installation, photo courtesy the author; Al in front of Amistad statue, City of New Haven Peace Commission (Facebook).

Join Now

Join Now