Years ago, during the early days of the Clinton administration, I was outraged, first by the Sistah Souljah episode, and later by the president’s treatment of Lani Guinier, who became the object of a vicious red-baiting campaign.

Guinier had been nominated to become the Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, until a gigantic whispering campaign initiated by an article in the Forward derailed her candidacy. Guinier was then dropped by the Clintons like a hot potato, ostensibly for her novel election ideas, like proportional representation and cumulative voting, but the red scare was most likely the hidden motive—her parents were left-wing activists.

Furious, I shared my anger with my grandmother, Pauline Taylor, herself an earlier victim of McCarthyism with whom I expected to find a sympathetic ear. After all, Grandma—a graduate of the Little Steel Strike, an NAACP chapter president, an associate of Eslanda and Paul Robeson, and a 1948 Progressive Party candidate for governor of Ohio—had more than a few struggles under her belt.

But much to my surprise, she looked at me and simply asked, “Well, what do you want, Bush?” Taken aback, I plied Grandma with argument after argument, but she simply smiled, ending the conversation with “You like Bush.”

Thus began a tug-of-war-like game between us: my railing against Clinton and my radical grandmother teasing me about my “love” for Bush.

Finally, one day, Grandma had a stroke. I rushed to her bedside, and Grandma looked up at me and whispered, “You like Bush.” Those were the last words she ever spoke.

Grandma had every reason to love and admire Lani Guinier. And she did. She was proud of her, as she was of Angela Davis, Eslanda Robeson, Shirley Graham Du Bois, Mae Mallory, and countless other heroic fighters for justice. But this love and admiration did not blind her to an estimate of the balance of forces that lay in George Bush’s quest for the presidency. A daughter of the Alabama coal field battles, and a victim of KKK, FBI, and company goon terror, Pauline Taylor knew full well what the stakes were. She also recognized, even if I didn’t yet, who her allies were, even if imperfect and vacillating. (And boy, was Clinton imperfect and vacillating!)

I think the same deep knowledge held true for the voters of South Carolina and other Super Tuesday states. They assessed, based on their historical experience and memory, the danger posed by Trump, the alt-right and KKK thugs grouped in and around his administration and cast a vote in what they perceived as their best interest.

I don’t know if it was the best choice, but it was certainly a reasoned and reasonable one.

Can a democratic socialist heading a broad left and broad center ticket win the presidency? Perhaps. Let’s recall that prior to his election, no one thought Obama had a chance. It’s also the case that women, LGBTQ, and even socialists have won offices in many places around the country. It’s not inconceivable that an energized, movement-based left-center campaign with a progressive platform and broad and flexible tactics could best Trump.

But Black voters did not yet see these conditions as being met. That said, it would be a mistake to draw the wrong conclusions.

This was not a vote against socialism or the left by Black “conservatives” or “moderates,” even with Rep. Clyburn’s red baiting of Sanders. Let’s also recall that another son of South Carolina, Jesse Jackson, deplored the red baiting, urging voters to “put aside the fearmongering and the red-baiting; take a look instead at the substance.”

With polls showing upward of 80% of African Americans favoring socialism, this cohort can hardly be described as anti-left. Rather, voters made a calculated decision as to who they thought was most able to beat Trump. Is it a miscalculation? Maybe.

But it’s worth considering why they drew this conclusion: Was it because they didn’t have confidence that white voters would rise to the occasion and show up for Sanders? Data showing a shrinking of the Sanders coalition in several state contests show they may have been right.

Or was it because Sanders, despite having made important steps in addressing African American concerns, had not yet gone far enough, or been bold enough? Could it be that Sanders’ brand of democratic socialism was not yet democratic enough in addressing the Black electorate’s equality concerns? Here at least one writer argued that Sanders “refused to adapt his ‘all lives matter,’ one-size-fits-all economic message to an intersectional one that explicitly acknowledges the effects of race on policy and governance.”

Perhaps, if Sanders, the socialist radical, made some radical proposals that would have captured the African American imagination, things would have been different: measures like a new Civil Rights Act, an endorsement of affirmative action in jobs and education, and measures to compensate for loss of black wealth (the largest in history) due to the 2008 subprime scandal. But all of this would have required a lot of groundwork, laid way before the South Carolina primary.

That said, let’s not forget the real advances that were made, in the first place, with the Latino vote. In addition, Sanders won the vote among 18- to 30-year-olds in South Carolina, proving that sections of the Hip Hop community and Black youth moved significantly in his direction. And as Sanders said in his March 11 press conference, his campaign won both the youth vote generally and the ideological debate around program. And that bodes well for the future.

It’s for the future that we fight, both immediate and long-term. Fighting for that future means respecting the independent self-organization and self-determination of the Black vote and perhaps even learning something from it.

Indeed, this is the only way to fight for and build the unity of the anti-Trump movement. Anything less is a prescription for defeat because, after its all said and done, folks are gonna join Grandma in heaven asking, “What do you want, Bush?” Or even worse, hear her scolding admonition, “You like Trump.”

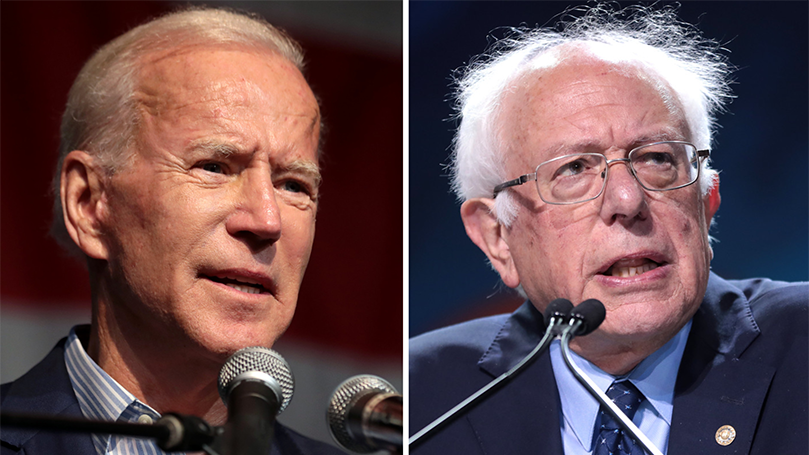

Gage Skidmore / Flickr CC BY-SA

Join Now

Join Now