“The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it” – Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach

The Communist Party has organized educational programs and institutions going back to its founding. These included schools to organize and train trade union organizers and party members called “Workers Schools,” which existed around the country, including in Pittsburgh, PA, where the likes of William L. Patterson taught courses. During the period of the fight against fascism and the building of the popular front, a network of mass and broad-based educational schools were developed like the Jefferson School of Social Science in New York City, the Chicago-based Lincoln School for Social Science — founded in part by William L. and Louise Thompson Patterson, the Samuel Adams School in Boston, Philadelphia’s Thomas Paine School, and the San Francisco Labor School.

The Jefferson School was founded in 1943, coming out of the Second World War, and opened in 1944. It was a successor to (and merger of) the New York Workers School and the School for Democracy that had a mass approach to community outreach and education as opposed to the narrow cadre training of new party members.

Also known as the “Jeff School,” it offered hundreds of classes each winter and fall on history, political struggles, and life under capitalism (with special attention to African American and women’s issues), as well as trade union affairs, instruction on Marxism, and related topics. It also delved into the cultural area with classes on literature, dance, music, health, interior decoration, and personal beauty on a budget.

Examples of such courses included early pre-requisites like “The Science of Society” which encompassed topics such as: the transition from feudalism to capitalism, the economy of industrial capitalism, the rise of the “democratic state” and the development of the labor movement, imperialism, colonialism, nationalism, socialism, fascism, the struggle against fascism, the United Nations, and the prospects for peace in the postwar world. Other elective courses were offered like “Marxism and the Negro Question,” “Marxism and the Woman Question,” and more. The traditional lecture-based education was further supplemented by the hosting of periodic public events including workshops, reading courses, musical concerts, and drama performances. There was also an extensive 32-week intensive “Marxist-Leninist theory” program in the “Institute of Marxist Studies” for developing party cadre.

Instructors and administrators of the school were paid for their efforts with the funds coming partly from course registration fees. The audience was predominantly oriented toward adult students, though a few courses were geared towards teenagers and children, and most of its attendees were women and trade unionists. An example of a course for teens was labeled “What is Marxism? – for Teenagers.” Herbert Aptheker, Claudia Jones, W.E.B. Du Bois, Doxey Wilkerson, Alphaeus Hunton, and Phillip S. Foner were among its instructors. Classes were also sometimes taught in Spanish (for example: “Principios de Marxismo”).

These schools, led by the CPUSA, did not replace club meeting educationals, nor did they replace special party training schools organized at the time by the Young Communist League or by the National Committee and the State Districts of the Party (for example, the Little Red School House). Schools like the Jeff School had a broad and mass appeal to the communities they were in, which reached those who were not in Communist Party orbits.

Notices of the school’s curriculum were posted and announced at local Communist Party clubs, columns in the Daily Worker, ads in the New York Times, and community postings and distributions throughout the city. Though the school was not intended to be a profit-making operation, modest registration fees were required for students to offset costs for instructional labor and other costs associated with the school. Scholarship aid was also made available for veterans, people of color, women, as well as trade union and community activists. The school was open to anyone, except “known enemies of the working class.”

The Jeff School also had other facilities including the Harlem Leadership Training School and the Maceo Snipes School, aimed at building African American participation in the Communist movement. It also hosted sub-branches in Harlem — like the George Washington Carver School: A People’s Institute — and in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and in other areas. The Jefferson School was eventually forced to close its doors in 1956 after several legal battles with the U.S. government’s Subversive Activities Control Board.

The Jefferson School stated its mission in this way:

“Forged out of the people’s war has come a weapon as important as plane and gun, food and factory. The classroom and public forum, the book and the pamphlet, the radio and town meeting have become mass weapons, as sharp and decisive as bullets in the struggle against fascism. …

“The Jefferson School of Social Science is founded upon the idea that the school today must help people meet the changing situations of a changing world. Education is not alone the means for transmitting the heritage of culture, of fact and information, of art and literature, of science and philosophy; it is the means for equipping people with the tools of understanding and with the scientific method for cutting a clear path to international security and to economic, social and political democracy. To this end, the Jefferson School dedicates itself to the study of the contributions made to the social sciences by the great pioneers in democratic thought and the leaders of the popular and working class movements in more recent times. …

“The School proposes to include as part of its program public forums and institutes on problems of the day, concerts, art exhibits and theatre presentations. Its object will be to make the School a focal point for the forward-looking educational and cultural life of the city, and to provide a meeting ground for the scientist, the writer, the dancer, the artist, the composer, and the people’s audience that seeks progressive ideas and new creative efforts.”

In the 1960s, Marxist historian and CPUSA member, Herbert Aptheker founded the American Institute for Marxist Studies, AIMS (not to be confused with the Jeff School’s Institute for Marxist Studies mentioned above), which had the goal of combatting “misrepresentations, distortions, slanders against, caricatures of Marxism and Communism. This would mean active polemical work, directed against press (periodicals and books) and all other media of agitation and propaganda, including organizations.” It aimed to give full publicity to its efforts with public debates, joint appearances and subscription newsletters, and gave a special attention to style: “vigorous, dignified, useful, down-to-earth, and national … crisp, humor[ous], militant.” Noting a “particular eagerness among youth – working and student,” the institute said it “would help train many.”

In the 1960s, Marxist historian and CPUSA member, Herbert Aptheker founded the American Institute for Marxist Studies, AIMS (not to be confused with the Jeff School’s Institute for Marxist Studies mentioned above), which had the goal of combatting “misrepresentations, distortions, slanders against, caricatures of Marxism and Communism. This would mean active polemical work, directed against press (periodicals and books) and all other media of agitation and propaganda, including organizations.” It aimed to give full publicity to its efforts with public debates, joint appearances and subscription newsletters, and gave a special attention to style: “vigorous, dignified, useful, down-to-earth, and national … crisp, humor[ous], militant.” Noting a “particular eagerness among youth – working and student,” the institute said it “would help train many.”

AIMS lasted about two decades and was meant to be a sort of “popular front” of left intellectuals inside and outside of the party. It hosted regular symposia and discussions and produced scholarly works including Marxism and Democracy.

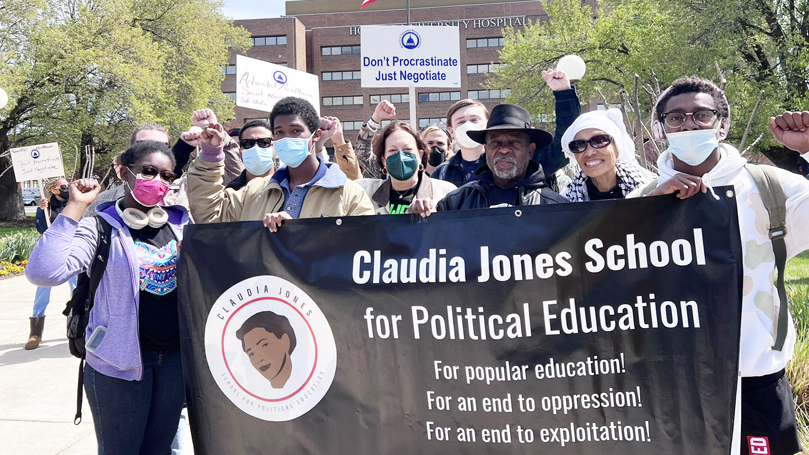

Fast forward to 2018, longtime leaders of the District of Columbia Communist Party (Washington, D.C. Club) came together to discuss the idea of a broad political education project that would help guide the renewed interest in socialism and democracy among the youth and democratic forces fighting Trumpism and supporting the Bernie Sanders movement towards a more Marxist and left orientation. The decision was made to name this political education project after Black Communist and Trinidadian immigrant, Claudia Jones, who was a major theoretical leader, journalist, and peace activist. Jones was deported during the McCarthyite period, which included a special attack on immigrants.

The basic idea was to organize a mass organization that would be led by Party cadre to not only become an educational institute of lectures and workshops, but to become a broad-based movement hub that can attract popular democratic and progressive forces.

Since “opening its doors” in February of 2020 (it has not yet obtained a physical community space due to lack of financial resources and skyrocketing rent costs in D.C.), the Claudia Jones School for Political Education has organized a variety of educational forums, panels, film screenings and discussions, international solidarity campaigns, and legislative fights. The exhaustive list includes:

- Saturday school and regular educational forums: a monthly-themed educational forum featuring engaging lectures from local community activists, party members, intellectuals, cultural artists, and more. The Claudia Jones School’s first iteration of this was a 7-month program starting in the summer of 2022 and lasting through the fall of 2022. The school also hosts regular community forums and panels on a variety of issues affecting working and oppressed people.

- Monthly film series: a monthly film viewing and discussion series related to different monthly themed topics featuring an open discussion with audience members.

- Campus study sessions: concentrated university campus student clubs were organized to bring popular and Communist education to the student bodies at local D.C. universities. These sub-branches of the Claudia Jones School are led by cadre of the Young Communist League and feature discussions on Marxist-Leninist ideology, Lenin’s classic texts, the National Question, and how these texts relate to student issues on the campus.

- Cultural performance nights and anniversaries: this is led by the Cultural Worker’s Committee of the Claudia Jones School, which has organized a series of open mic nights featuring local poets, spoken word artists, singers, and theater performers related to a theme that affects the people of Washington, D.C. — namely, gentrification and housing displacement. We have also organized an annual celebration of our founding during Black History Month and close to Claudia Jones’s birthday (February 21, 1915), which is typically a lineup of cultural performances, speakers from among local organizations and activists, and food prepared by local street vendors. We have also organized local Communist drag shows, showcasing the revolutionary trend among the queer liberation movement, and supporting local drag artists due to the vibrant LGBTQ+ community in the district.

- International solidarity and the fight for peace: due to its pertinent location in Washington, D.C., the school has been able to develop close relations with ambassadors of countries with progressive governments. One example is the annual hosting of a local festive event in celebration of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua. Another example is our leadership in a coalition, the D.C. Network for U.S.–Cuba Normalization, which recently was instrumental in the passage of a local D.C. Council resolution calling on the U.S. federal government to restore its relations with Cuba — including by lifting the more than 60-year blockade, and removing Cuba from the State Sponsors of Terrorism list. The Claudia Jones School has also participated in annual delegations to Cuba and Nicaragua to develop exchanges with peoples suffering from U.S. imperialist policy.

- Immigrant rights: the school has played a leadership role in the fight for immigrant rights throughout D.C., in particular its participation in the passage of the Local Voting Rights Amendment Act, which extended local voting rights to 50,000 residents. The Claudia Jones School is also a component in the Amigos Park Coalition, a neighborhood project which is fighting for a public and neighborhood-governed space in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

- Trade unions and labor rights: the school has also taken part in canvassing to assist legislative fights around restaurant workers — specifically tipped workers, and domestic workers. We partnered with local organizations to pass Initiative 82, which phases out the tipped minimum wage in the District of Columbia, and also testified at D.C. Council hearings in support of the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. The latter will expand labor and human rights protections to domestic workers in D.C., who are predominantly immigrant women of color.

- Community newsletter: the school sends out a monthly community newsletter showcasing its work in the community, legislative fights, coalition programming, educational forums, meetings, donation solicitations, and local news.

For future programming, the Claudia Jones School plans to revive the D.C. Friends of the People’s World Paul Robeson Award, to be given on Paul Robeson’s Birthday (April 9). The school also has participated heavily in the revival of the D.C. Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, co-sponsoring events and educational webinars on the topics around political repression and community control of the police.

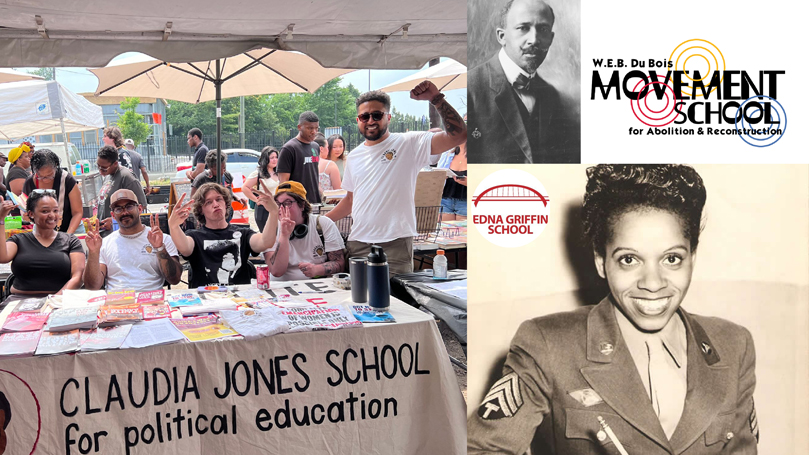

This work has already had a significant impact on people who are not members of the Communist Party, but who are close to us. One includes the recently founded W.E.B. Du Bois Movement School for Abolition & Reconstruction coming out of West Philadelphia, P.A., and the Edna Griffin School for Social Justice in Des Moines, Iowa. We have also partnered with local projects led by Black Women Radicals, like the School for Black Feminist Politics. We also see some influence in the recently developed Detroit Union Education League, which seems to also be following the trajectory of the William Z. Foster-led Trade Union Educational League. It is unfortunate, however, that other recent Marxist educational projects have been shut down due to lack of financial support like the Center for Marxist Education in Boston, MA and the St. Louis Workers’ Education Society in St. Louis, MO.

How can other local CP clubs and districts build their own popular education schools in their respective areas? We offer a step-by-step guide, based on our own experience in D.C.:

- Organize a leading party collective in your district (this could be the executive committee itself, if it is a small club) to begin brainstorming what a political community education project or institution could look like.

- Determine your relationship to the community you are organizing in.

- Who are the main progressive forces that have the potential to change the balance of forces in your region?

- What is your target audience?

- What is the makeup of trade unions in your area? And what is your relationship to them?

- Are there any cultural workers that you have relations with and would they be willing to participate in programming for your project?

- What sort of options exist for a central community space for people to gather and attend events?

- What are the rental space costs?

- How to fundraise?

- Organize a board of directors to manage and administer the programming of the space.

- Determine the programming.

- Think about what would be the main issue that will unite and broaden the scope of forces that would attend your event. For example, consider: abortion rights, immigrant rights, labor organizing, fighting against racism, LGBTQ+ rights, housing

- What will the form of the programming be? It could be cultural, lecture-based, workshops, study groups, social media, film / documentaries, or social events

- Set up a budget

- Organize sub-committees with party cadre leading different projects (depending on your resources and capacity)

- Determine your relationship to the community you are organizing in.

- Begin organizing a regular set of monthly, quarterly, or annual events to begin mobilizing the community and organizing them into the educational project

- Invite them to participate in the project collectives to be part of the democratic process

- Be honest about your limitations

- Be transparent about your politics

- Maintain a contact list and begin building out the infrastructure of the organization

- Develop relationships with trade unions, community organizations, elected officials, etc.

- Co-sponsor events to help with costs and capacity building

- Fundraise, fundraise, fundraise!

- You will not be able to survive without financial resources. Develop infrastructure to bring in regular streams of income and maintain a budget to stay on top of expenditures.

References:

“No Varsity Teams”: New York’s Jefferson School of Social Science, 1943-1956, Science & Society, Vol. 66, No. 3, Fall 2002, 336-359

The Most Dangerous Communist in the United States: A Biography of Herbert Aptheker by Gary Murrell

Images: The Claudia Jones School shows support for striking hospital workers by Claudia Jones School for Political Education (Twitter); Students at the Jefferson School of Social Science (CUNY); Herbert Aptheker transferring W. E. B. Du Bois papers to University of Massachusetts. Seated to his right is Shirley Graham Du Bois (Wikipedia); Attendees of an International Workers Day cultural event with the Claudia Jones School for Political Education by Claudia Jones School (Twitter); Collage: Claudia Jones School for Political Education at the ONE DC Juneteenth event by Claudia Jones School (Twitter) / W.E.B. Du Bois by US Department of State (CC BY-NC 2.0) / W.E.B. Du Bois Movement School for Abolition & Reconstruction / Edna Griffin (Edna Griffin School for Social Justice) with Edna Griffin School logo (Twitter)

Join Now

Join Now