Hershel Walker was an African American St. Louis, Missouri trade unionist and civil rights leader with an unparalleled degree of commitment to the struggles for peace and justice. He devoted his life to the movements for social transformation and joined workers across the world in the struggle for equality, workers’ rights, peace, and socialism.

Born February 20, 1909, in Arkansas, Hershel Walker moved to St. Louis in 1929. In 1930, he joined the Young Communist League (YCL). It was during this time that he acquired an undying devotion to the working class, internationalism, and socialism.

When he joined the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), he also joined the St. Louis Unemployed Council, which sought to use mass mobilization tactics to prevent evictions and starvation during the Great Depression. On July 11, 1932, he took part in an Unemployed Council organized march on City Hall involving 3,000 Black and white men and women demanding relief for the unemployed. That struggle stopped St. Louis officials from cutting off food to families of the unemployed.

Unemployed Council marches became a part of everyday St. Louis life. It was an early example of Communists challenging racism and Jim Crow in action in St. Louis. Black workers, like Walker, carried that philosophy into union organizing as well, seeking to unite across racial, ethnic, and gender divides.

These efforts were part of a broad-based campaign for social transformation in the 1930s. The Unemployed Councils, led by the CPUSA, along with trade unions, were the organizations that fought for unemployment insurance, social security, the shorter work week, and the passage of the Wagner Act, which gave unions the legal right to organize.

Walker was part of the early campaigns leading to the modern civil rights movement. He was part of what is now called the Long Civil Rights Revolution. He was a member of the local chapter of the International Labor Defense, which helped in the defense of the Scottsboro Nine in Alabama. The Scottsboro case brought international attention to racism, Jim Crow, and the cruel injustices of the South’s legal power structure.

It was only through the efforts of activists like Walker that the nation began to be aware of the brutality of “southern justice.” Their activities planted the seeds of combining legal and mass protest tactics, while also bringing international pressure to bear against Jim Crow. Black Popular Front organizations, such as the National Negro Congress and the Southern Negro Youth Congress, would continue this tradition starting in the mid-1930s into the mid-1940s.

In 1939, Walker helped organize support for 1,700 Black and white sharecroppers who were forced off their land in the Missouri Bootheel region, due to the policies of the landowners who sought to avoid paying the sharecroppers for their work. Like sharecroppers in Alabama and elsewhere, in the face of violence and terror, Missouri sharecroppers organized with the help of Communists like Walker.

In 1942, Walker went to work at the Wagner Electric Company, where he stayed for 29 years. He belonged to the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers Union Local 1104, an affiliate of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The UE was then partly led by well-known Communists, such as William Sentner, who negotiated the UE-Wagner Electric contract.

During World War II, Walker and other progressive trade unionists organized against racist hiring and promotion policies that then predominated at Wagner Electric. When he started, Black workers were hired mainly for janitorial and transport jobs. He organized union members to fight these racist policies.

He also worked with A. Philip Randolph’s March on Washington movement to protest racist hiring practices at the Small Arms U.S. Cartridge plant on St. Louis’ Goodfellow Blvd., a protest that resulted in the company’s hiring a percentage of Black workers that corresponded to the Black population of St. Louis.

Unfortunately, after the war’s end — and despite the sacrifices Communists domestically and internationally had made to defeat fascism — the war-time alliance with the Soviet Union was broken and Communists became the new enemy. By the early 1950s, Walker and those like him who sought to connect race and class were under siege as the Red Scare ascended. Like other Communists, Walker was surveilled by the FBI.

Mr. Walker did not slow down, though. He persevered in efforts to address racial, economic, and gender inequality. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Walker joined the Civil Rights Congress, which continued to challenge racism and Jim Crow. In December 1951, it released the historic We Charge Genocide petition to the United Nations. Walker helped in the defense of Willie McGee and raised awareness about the brutal death of Emmett Till in Mississippi.

Also in 1951, Walker was a delegate to the founding convention of the National Negro Labor Council and established the St. Louis branch. The NNLC set up Affirmative Action Committees in local unions and won a major local victory for African American women by challenging Sears-Roebuck’s hiring and promotion policies. Walker organized Black and white trade unionists and community supporters to march in front of the Sears store on Kingshighway, demanding that Black women be hired as salesclerks. Their tenacity, despite FBI and Police Red Squad harassment, was remarkable, and it paid off. Sears ultimately agreed to their demands.

After that victory the group moved forward in a successful campaign to get Black drivers hired at the local bus and streetcar companies. Walker’s activism during this period — like that of Edna Griffin and other Black Communists at the local and national level — challenges the dominant narrative among traditional historians that the CPUSA saw nothing but retreat and decline during the Red Scare, Cold War, and post-1956 period. Coupled with errors, inaccuracies, and omissions, their narratives are permeated with racism as well, often completely ignoring the contributions of Black Communists like Walker and Griffin, as well as William L. Patterson, Benjamin Davis Jr., and Claudia Jones.

Regardless, Walker helped desegregate theatres in St. Louis and East St. Louis, too. Recall, this is four years before the Montgomery Bus Boycott and 13 years before the establishment of affirmative action policies nationally. His civil rights activism continued through the decade.

In 1961, as red-baiting eased some, Walker was asked to speak at a rally at St. Louis University. Like other Communists, such as Gus Hall, Herbert Aptheker, and James Jackson, he contributed to the wave of wildly successful college and university Communist speaking engagements throughout the early and mid-1960s.

In 1961, as red-baiting eased some, Walker was asked to speak at a rally at St. Louis University. Like other Communists, such as Gus Hall, Herbert Aptheker, and James Jackson, he contributed to the wave of wildly successful college and university Communist speaking engagements throughout the early and mid-1960s.

Walker was a valued part of every major struggle for justice in the St. Louis area in the 1960s and 1970s, including the anti–Vietnam War peace movement.

As a Marxist, Walker’s focus was sometimes national and international. However, his activism was always centered on winning concrete benefits for working-class people. He was involved in the struggle to mobilize against Jefferson Bank’s discriminatory hiring policies, one of the defining moments of civil rights struggles in St. Louis. He helped mobilize St. Louis residents for the 1963 March on Washington.

In 1972, he helped organize the St. Louis chapter of the Angela Davis Defense Committee and in the following year helped form the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression. In 1977, Walker began working for the American Friends Service Committee. He was a leader in the campaign to save Homer G. Phillips Hospital, Missouri’s premier Black hospital that had trained the largest number of Black nurses and doctors in the world.

Throughout the 1980s, Walker was still working for the National Alliance, and was deeply involved in the South African anti-apartheid struggle through the CPUSA-led National Anti-Imperialist Movement in Solidarity with African Liberation. He walked the picket line during the Shell Boycotts. In 1983, Walker also helped elect Communist Kenny Jones to the St. Louis City Board of Aldermen (Ward 22), who was known for leaving copies of the CPUSA’s newspaper in the aldermanic chambers. Though most people tend to focus on the Gus Hall–Angela Davis presidential campaign, throughout the 1980s Communist candidates cumulatively received hundreds of thousands of votes in down-ballot elections.

Tragically, in 1990 Hershel Walker was killed in a car wreck while on his way to deliver petitions for the campaign to save 4,000 jobs at Chrysler Plant #1 in Fenton, Missouri. He was well-known among the members and leaders of the United Auto Workers union and the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists.

Every year since his death (until COVID), the Missouri/Kansas District has held an annual awards breakfast in Walker’s honor where St. Louis area labor and community activists, as well as elected officials, are recognized for their leadership. The breakfast, usually attended by around 150 of St. Louis’ most well-known progressive activists and elected officials, is supported by labor unions and community organizations.

Hershel Walker understood that the struggles for equality, workers’ rights, peace, and socialism are all connected. He was a life-long member of the Communist Party, USA, and chair of the Missouri/Kansas District for 15 years.

He spent over 60 years of his life fighting for a better world.

For recorded interviews of Walker, click here.

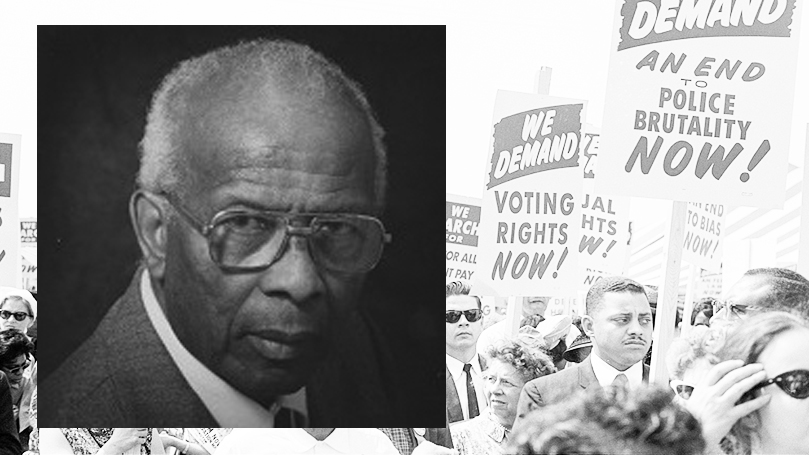

Images: Top, portrait of Walker, People’s World/Daily Worker Photo Archive/Tamiment Library NYU; background photo, Library of Congress, (no known restrictions); Frank Chapman, Charlene Mitchell, and Hershel Walker, Frank Chapman Facebook page.

Join Now

Join Now