Hunger, homelessness, and evictions were features of the Great Depression in the United States. Jobs disappeared and working conditions deteriorated. Some “250,000 teenagers were on the road.” And how many others? By 1933 one-third of farm families had lost their farms. Unemployment that year was 25 percent. The lives of working people were devastated.

The federal government’s New Deal led to political and social reforms. Now the U.S. government once more has a big economic crisis on its hands, this one associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s providing mostly financial relief, with a lot going to big economic players.

During the Great Depression, people responded at the grassroots level too, particularly in urban neighborhoods. In the midst of another economic crisis, it makes sense that something similar happen again. This report is about a grassroots tool of 90 years ago and about its potential usefulness now. As will be seen, assaults on working people are harmful enough now to provide ample justification for possibly picking up that tool again.

In fact, workers and their families created their own means of rescue as the Great Depression took hold. Demanding food, housing, and jobs, they organized, agitated, and prodded politicians to provide relief and reform. They did so through the Unemployed Councils. New in early 1930 and organized by the Communist Party USA, the Councils took root in many cities.

They came into being step by step. In 1929 the Comintern decided that the capitalist crisis manifesting as a worldwide economic depression required a “revolutionary offensive.” Responding, the CPUSA formed its Trade Union Unity League. That organization set up “Councils of Unemployed Workers.” According to a Party publication, “the tactical key to the present stage of class struggle is the fight against unemployment.”

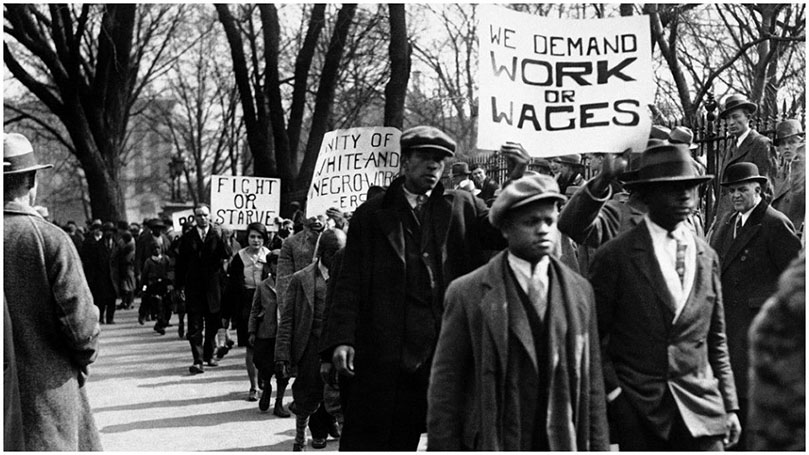

At once the Unemployed Councils organized unemployment protests that swept across the country. March 6, 1930, was designated as “International Unemployment Day,” a day when one million demonstrators filled the streets of cities.

Thousands of police violently attacked more than 100,000 workers filling New York’s Union Square. Demonstrations continued over several months in many cities, as did police harassment. New recruits flooded the Unemployed Councils. March 6 became an annual occasion for repeat nationwide demonstrations.

The Unemployed Councils, functioning autonomously in urban neighborhoods, pressured local relief officials to assist individuals and families. They badgered utility companies to restore gas or electricity to non-paying households. The Councils organized rent strikes beginning in 1931. They recruited crowds that, having overwhelmed the police and local officials, allowed evicted tenants to return to their dwellings. Council activists besieging city offices demanded reduced rents and no more evictions.

Unemployed Councils helped provide impetus for New Deal reforms.

The Unemployed Councils reached out to Black workers, even in southern cities. Actions of the Unemployed Councils helped provide impetus for New Deal reforms like unemployment insurance, protection of labor rights, and security for elderly Americans and children.

Hunger marches organized by the Unemployed Councils took place in various cities from 1931 on. The police killed five people marching in the “Ford Hunger March” in Dearborn, Michigan, on March 7, 1932; 60,000 people joined the funeral procession. At a national hunger march converging on Washington on December 7, 1931, marchers demanded unemployment insurance and a “social insurance system to cover maternity care, illness, accidents, and old age.”

A year later even more marchers, mainly Communist Party members, descended on Washington for a repeat national hunger march. They called for jobs, relief measures, taxation of the wealthy, and an end to racial discrimination. Members of Congress met with march leaders. The Roosevelt administration would soon direct states to expand relief efforts and promote job programs.

The CPUSA set up “The Unemployed Council of the U.S.A.” in 1931 in part to deal with rapid turn-over of community activists affiliating with local Councils. The problem would remain. The national Council provided local Councils with guidance on national and international issues. Even so, individual Councils focused primarily on the hardships and needs of workers and their families, in their own neighborhoods.

The national organization in 1932 published a 20-page pamphlet titled: Fighting Methods and Organization Forms of the Unemployed Councils: A Manual for Hunger Fighters. The introduction begins:

The Unemployed Councils base their program on a recognition of the fact that those who own and control the wealth and government are willing to allow millions to suffer hunger and want in order that their great wealth shall not be drawn upon for relief. We know that the living standards of employed and unemployed alike will be progressively reduced unless we organize and conduct united and militant resistance. We know that the amount and extent of relief which the ruling class can be compelled to provide depends upon the extent to which the unemployed and employed workers together organize and fight.

The trajectory of the Councils changed. New Deal relief programs took effect, and the Communist Party, following the lead of the Comintern, turned to alliances with other progressive forces. This was the Popular Front. The Unemployed Councils gradually gave way to the Workers Alliance of America, formed by the CPUSA in 1936 and based in Washington. The Alliance welcomed Socialist Party unemployment groups and pacifist A. J. Muste’s Unemployment League. Its activities centered on lobbying for relief measures and worker protection.

Pandemic and Sick Economy

The Unemployed Councils were new and, within the context of that era, were extraordinary. They attended solely to the needs of workers. They were based in local communities. And they were a creature of the Communist Party. Their time may have come again.

One determining factor is the severity of the current economic collapse and its impact on the lives of working people. Indeed, this crisis looks like it’s going to hurt workers and their families as much as did the Great Depression. The assumption here is that the extraordinary nature of the present danger to working Americans must be appreciated in order to accept the idea that an extraordinary instrument of repair, the Unemployed Councils, is required once more.

Unemployment—As of early June, 42.6 million U.S. workers had filed unemployment claims. The official unemployment rate was 14.7 percent in April, 13.3 percent in May. In May the official rate for Black people was 16.8 percent and for Latinos, 17.6 percent. However, “a quirk in BLS methodology” (Bureau of Labor Statistics) misclassified people absent from work due to COVID-19. The actual unemployment rate in April was 23.6 percent. According to economist David Ruccio, the total of the underemployed plus the officially unemployed represents 31 percent of the U.S. labor force.

Significantly, “39 percent of employed people in households making less than $40,000 lost their job or [had] been furloughed in March.” Official unemployment figures don’t include the chronically non-employed. The Brookings Institute reports that, in 2017, 15 percent of “American men between the ages of 25 and 54” were not working for a variety of reasons, imprisonment and others.

Housing loss—That many workers can’t pay rent sets the stage for evictions. Signs of tenant resistance have cropped up. For instance, Rent Strike 2020 is a “disaster relief organization owned and controlled by regular working people.” It demands that states “freeze rent, mortgage and utility bill collection for 2 months, or face a rent strike.” According to the website westriketogether.org, 33 percent of residential tenants didn’t pay rent in May, and almost 350,000 tenants have signed a rent-strike pledge.

Access to health care—Many of the newly unemployed have lost their employer-based health-care insurance. They can’t pay for health care and soon will total 11 million working people. A crisis of access existed already. In 2018, no less than 30.1 million people under the age of 65 lacked health insurance. In 2019, 28 percent of adults with employer-based health insurance were underinsured.

Food is short—The Brookings Institute recently declared, “By the end of April, more than one in five households in the United States, and two in five households with mothers with children 12 and under, were food insecure.” In April, “21.9 percent of households with nonelderly adults were food insecure.”

Dairy farmers are dumping milk. Hog and chicken farmers are killing their animals, and growers are plowing crops into the ground. These are “scenes reminiscent of the Great Depression,” and, says the Guardian, “overproduction will sour the market.” This is a crisis of capitalism.

Racism—Non-white populations are vulnerable. They are generally sicker than white people from illnesses like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma, HIV, morbid obesity, and kidney disease. That’s mostly because racial discrimination encourages low-quality health care, reduced access to care, and lack of preventative care. Racism forces a disproportionate number of non-white workers to live in places full of environmental toxins. The stress of living under racism may lead to or worsen physical illnesses.

These points of vulnerability translate into high risk, plainly evident as African Americans and Latinos confront the COVID-19 virus. One report has it that, as of June 9, the “COVID-19 mortality rate for Black Americans is 2.3 times as high as the rate for Whites and Asians, and 2.2 times as high as the Latino rate.” Latinos, 18 percent of the U.S. population, in April accounted for 25 percent of COVID-19 deaths. Death rates for Blacks and Latinos living in cities range from two to four times higher than white people living in cities.

At issue here is suffering caused by economic crisis. Resilience helps economically-abused victims survive, and resilience may be in short supply for a class of people hit exceptionally hard by the COVID-19 virus. Besides, most of these victims are members of the working class, and they are more likely than higher-income employees to have been working “in public-facing occupations” and to experience “inequitable distribution of scarce testing and hospital resources.”

Women are victims—According to one report, the “hardest hit [during the pandemic] will be the world’s women and girls and populations already impacted by racism and discrimination… Women are 70 percent of the global health workforce and the majority of social workers and caregivers.” They “deliver 70 percent of global caregiving hours.” The report does not mention that these multitudes of women doing necessary work belong overwhelmingly to the working class, in the United States and elsewhere.

The broad conclusion here is that the impact of this economic downturn has been and will be disastrous for working people, extraordinarily so. The usual governmental remedies seeking to balance worker and business interests won’t adequately serve the working class. Too often what is done ends up pitting the needs of workers against the needs, real and imagined, of those who lack for nothing. And guess who loses out!

The Unemployed Councils provided an extraordinary boost in their time to workers and their families. A return engagement is in order, in one form or another.

A peripheral concern must be attended to. The argument may be advanced that this economic crisis will be brief, so why go to all the trouble? No, it will not be brief. The U.S. delay in preventing spread of the virus allowed the pandemic to build. Lax social-distancing and irregular quarantine will ensure its prolongation. A comprehensive regimen of testing, tracing of contacts, and quarantine would have made all the difference, according to a medical expert. The virus has taken charge of the U.S. economy. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said, “We are now experiencing a whole new level of uncertainty, as questions only the virus can answer complicate the outlook.”

Besides, an already flawed U.S. economy doesn’t rate a quick fix. It was already stumbling due to “stagflation” (inflationary tendencies co-existing with stagnant economic output), unpayable debt, and financialization. The latter signifies diminished productive capacity.

Correlations

This report on the potential usefulness now of Unemployed Councils is of an introductory nature. Even so, it does appear that the Councils have great potential to meet the needs of many working people in great trouble now in the United States—but not all of them.

The Councils’ usefulness would rest on conditions under which they would be applied. One would be that they deal with unemployment, lack of housing, and hunger. These problems are presenting now in roughly similar fashion as in the 1930s. Another would be that Councils of today pay heed to features characterizing their performances then. These included attention to workers’ most pressing social and economic needs, rapid response, militancy, and long-term revolutionary goals. All were crucial to the Councils’ achievements.

Other problems of today don’t fit with interventions of the kind offered years ago by Unemployed Councils. These are reduced access to health care, racial inequalities, and gender inequalities. They were as problematic then as they are now, but society and even worker organizations of that time either accepted the injustices they represented or weren’t prepared to engage with them.

Those still unmet needs do demand attention now, and any version of renewed Unemployed Councils would have to accommodate them. The difficulties in doing so represent a threshold that revived Unemployed Councils would have to overcome. How that would happen without major revamping is unclear.

This inquiry is incomplete. The feasibility of bringing back Unemployed Councils hasn’t been dealt with. At first glance, the people power needed for strengthening new Councils and for maintaining their working-class orientation looks to be missing. It was different earlier. Communist organizers drew upon enthusiasms left over from socialist and workers’ movements that had peaked two decades earlier. They took new encouragement from socialist revolution in Russia in 1917. But to know about any resulting advantage and much more, detailed exploration is required.

Worker-to-worker solidarity, the business of the Councils, never involved ideas of mutual aid often associated with anarchist or libertarian political movements. The Councils never embraced doctrinaire resistance to state authority, or self-reliance of local communities, or exclusively horizontal power relationships. This is another instance of investigation left for another day.

Published in Monthly Review, June 9, 2020.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Join Now

Join Now