It started in Loudon County, Virginia, and now it has metastasized all over the United States. In state after state and county after county, raucous scenes have been enacted at school board meetings, in which groups purporting to represent parents, extremely angry and worried about evil that is supposedly being done to their children, have shut down board meetings, caused administrators and teachers to resign, and created a multi-faceted uproar. Now the uproar is increasingly involving death threats against educators.

The complaints expressed by these groups include the accusation that anti-white “critical race theory” is being imposed on their children with the result that the children are made to feel uncomfortable, that efforts by schools to be more sensitive to the needs of minorities and LGBTQ children are a violation of parents’ rights to shield their children from “sexually explicit” information, including library books, and that mask mandates designed to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic are a violation of the parents’ rights to control their children.

The parents who are pushing these agendas claim to be expressing the views of all parents and working for the protection of all children. But this is far from the case. They are mostly well-off suburban white people. Organizations dedicated to defending the interests of low-income, minority, and LGBTQ youth are not involved in this campaign and, in fact, mostly oppose its goals and tactics.

The parents who are pushing these agendas claim to be expressing the views of all parents and working for the protection of all children. But this is far from the case. They are mostly well-off suburban white people. Organizations dedicated to defending the interests of low-income, minority, and LGBTQ youth are not involved in this campaign and, in fact, mostly oppose its goals and tactics.

In one situation after another, these parents complain that their children are hearing and reading things in school that make them (both the children and the parents) “uncomfortable.” Much of the discussion around this “uncomfortableness” complaint has to do with the history of racism in this country, or LGBTQ inclusion discussions and policies. The thing has gotten so extreme that the newly elected far-right governor of Virginia, Republican Glenn Youngkin, set up a special hotline for parents to snitch on teachers who say things in class that might make their children feel “uncomfortable.”

This new development has to be seen in the context of Virginia’s history of slavery, Jim Crow, and institutional racism. Virginia was the first colony to which enslaved Africans were brought in numbers. The wealth of white landowners in Virginia was gained by the dispossession of the indigenous population and the widespread, intensive exploitation of slave labor. Virginia also was known as a center for the “breeding” of slaves for shipment farther south, for example to the cotton plantations.

During the Civil War, Virginia constituted the main political center for the Confederacy. (Richmond, today Virginia’s capital, was also the capital of the Confederacy until near the end of the war, when the Confederate leadership fled to Danville, also in Virginia.)

Subsequent to the Civil War, Virginia was a hotbed of “Jim Crow” laws and practices. It was one of the places in which the “one drop” theory was developed and enforced, along with viciously segregationist policies. A major ideologue of “one drop” and racial eugenics was Walter Plecker, Virginia’s Registrar of Vital Statistics, in charge of issuing birth certificates, which at the time designated the “race” of the baby. He used this powerful position to fiercely enforce the racial segregation policies Virginia shared with the rest of the South. He also used his power to “disappear” Virginia’s indigenous population, on the basis of the idea that self-identified “Indians” likely had at least a drop of “African blood.”

From the late 1950s to 1964 in some places, Virginia’s state government showed itself ready to destroy the state’s public school system rather than conform to the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision which prohibited racial segregation in public education. This official government policy, called “Massive Resistance,” against equality for African American schoolchildren happened within the living memory of many older Virginians of all races. Massive Resistance was eventually defeated, but the legacy of segregation and inequality has continued in many institutions in this state, including access to jobs, housing, schools, health care, and other things. In many areas to this day, zoning rules and de facto segregated housing patterns have perpetuated the racial segregation that Massive Resistance was supposed to protect by law.

Virginia is a “right to work” state, a situation which has weakened labor unions and hurt the interests of our working class. Few are aware of the racist roots of “right to work” laws like Virginia’s. In fact, when such laws were being proposed from the 1930s on, a major argument that their big-business supporters made was that if there were unions everywhere, and “closed shops,” white men and women would be forced to work alongside African American women and men in the same workplaces. In the racist atmosphere of the South (and not only in the South), this undercut efforts to advance union and workers’ rights in states like Virginia.

All of these things and more are examples of how our history of racism, stretching back to the Jamestown settlement, still has a strong influence on the daily lives of millions of Virginians today. Are these matters so unimportant that the public should not be aware of them? Is the fact that many businesses and other institutions were able to build up their wealth and power through their involvement with slavery and Jim Crow something that should be swept under the rug and forgotten?

Yes, talking and reading about these things should, and I hope will, make people “uncomfortable.” But is that a bad thing?

I wish that when I was a child and a student in elementary and secondary school, and then in undergraduate and graduate studies, my parents, my extended family, and the institutions in which I was educated had done more to make me feel this kind of discomfort.

The story of my own miseducation on two continents

I went to my first years of elementary school in an English-medium public school in Pretoria, South Africa—the country where I was born. My Afrikaans-speaking parents deliberately sent me to a school where classes were mostly in English because they did not agree with the heavy doses of right-wing propaganda that the recently installed National Party government was foisting on the country, as part of its effort to ideologically bulwark the “apartheid” system.

But in some respects, the experience I had in the English-language school was pretty bad anyway. Despite its being a government school, Bible lessons were obligatory. One time the teacher asked us to draw pictures illustrating scenes from the Bible. I don’t remember what I drew, but a clever and precocious classmate chose to illustrate the scene from Genesis in which Noah (the guy with the ark) gets passed-out drunk and falls asleep with his genitals in full view (Genesis 9: 20-21). She had the wisdom not to draw the genitals, but she showed Noah with a huge red nose. The teacher was furious, but we children were much amused.

Every morning we had to line up in orderly rows outside the school for prayers and to sing “God Save the King” — South Africa was not yet a republic and the monarch at the time was George VI. If you fidgeted or didn’t pay attention, you were chastised.

Nothing was told to us children, either by the teachers or our adult relatives, about the horrible state of race oppression that characterized the country long before official apartheid was started after the elections of 1948. The only Black South Africans I ever met as a child were adults who worked in the city but were not allowed to bring their families into white areas. So I never met Black children my own age until I came to the United States. And the issue of race and racism, in its vitally important historical context, was never discussed in front of us children. It was thought that this might make us feel uncomfortable, but also that it might eventually break up white unity against the “swart gevaar” (Black danger). For me, the result of this is that I never realized until much later that some of the members of my extended family were actual fascists — but that other relatives actually played a part in the anti-apartheid movement.

Nothing was told to us children, either by the teachers or our adult relatives, about the horrible state of race oppression that characterized the country long before official apartheid was started after the elections of 1948. The only Black South Africans I ever met as a child were adults who worked in the city but were not allowed to bring their families into white areas. So I never met Black children my own age until I came to the United States. And the issue of race and racism, in its vitally important historical context, was never discussed in front of us children. It was thought that this might make us feel uncomfortable, but also that it might eventually break up white unity against the “swart gevaar” (Black danger). For me, the result of this is that I never realized until much later that some of the members of my extended family were actual fascists — but that other relatives actually played a part in the anti-apartheid movement.

As I grew older and after I moved to the United States with my family, I developed a resentment about the fact that “nobody had told me about these things” or educated me properly on political and social justice issues that later determined the course of my adult life. This kind of “discomfort” was the beginning of my political radicalization.

In short we were not taught history, we were taught worship of national symbols — historical idolatry.

So I finished elementary school and high school in the United States. But especially in high school (in Newark, Delaware) I met with the same evasiveness, hypocrisy, and miseducation about the real state of the world and of this country especially. In high school, the approach to U.S. history seemed to be taken from Margaret Mitchell’s book Gone with the Wind and the Hollywood film derived therefrom. The role of slavery as a cause of the Civil War was glossed over, and the history of Reconstruction was utterly falsified. The Alamo was portrayed as a glorious thing, and the U.S. seizure of more than half of Mexico’s national territory in 1846–48 was presented as a good thing. The genocide inflicted on the indigenous population was not mentioned at all. Woodrow Wilson was presented as a great statesman and national hero; nothing was said about his racism or his government’s repression of dissent. In short we were not taught history, we were taught worship of national symbols — historical idolatry.

Things improved in college and grad school (at the University of Delaware, American University in Washington, D.C., and then Northwestern University for my masters and doctorate). This was as much due to interactions among the students, and access to superior library materials, as to the faculty and the courses. Whatever the reason, my eyes and those of my fellow students were opened little by little. It helped that this was during the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the protests against the Vietnam War. Contact with students of many races, ethnicities, and national origins was a huge part of this awakening. Very few of the faculty at the institutions of higher learning I attended were themselves leftists, let alone Marxists or communists, but the interactions among the students themselves made up for this.

Things improved in college and grad school (at the University of Delaware, American University in Washington, D.C., and then Northwestern University for my masters and doctorate). This was as much due to interactions among the students, and access to superior library materials, as to the faculty and the courses. Whatever the reason, my eyes and those of my fellow students were opened little by little. It helped that this was during the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the protests against the Vietnam War. Contact with students of many races, ethnicities, and national origins was a huge part of this awakening. Very few of the faculty at the institutions of higher learning I attended were themselves leftists, let alone Marxists or communists, but the interactions among the students themselves made up for this.

And we read every damn thing we could get our hands on.

In the summer of 1967 I spent time on a Native American reservation in Arizona, doing linguistic research. This was another radicalizing experience, because of the raw racist anti-indigenous comments I heard from Arizona whites, and because it taught me that even scientific research can be distorted for anti-people purposes, including academic careerism.

From student to educator, the educator reeducated

My first academic job was teaching anthropology at the University of Illinois-Chicago. I enjoyed this job immensely, but I have often said since, and I mean it, that I learned more from my undergraduate and graduate students than they learned from me. This was because they were overwhelmingly working-class students of all races and had already seen the class struggle and anti-racist struggle in action, in the suffering and resistance of their blue-collar and minority families. This was the best part of my own education, and it hooked me on grassroots activism, for working-class and labor struggles, and especially for the anti-racism struggle. But most of my academic colleagues did not see things this way. They thought of their students as “empty vessels” (to use Paulo Freire’s phrase) into whose heads they, the academic experts, were duty bound to pour “real” knowledge. The students came to class with a lot of knowledge already, but this was not considered to be real knowledge. I learned to see the educational process as a dialogue between students and teacher, to which both contribute information, analysis, and insights. From that perspective, I could never see my students as being unprepared and a nuisance to teach, a complaint I constantly heard from some of my colleagues at the university. This continued to be my pedagogic orientation until I left Chicago in 2004.

What does all this have to do with the attack on critical race theory and the school board wars?

This: The astroturf “parents’” organizations that the ruling class has recruited as the attack squads in this struggle are like the worst actual teachers one could imagine. And the teachers they are attacking are the best there are, which is why they are attacking them. This attack also is linked to agendas of school privatization and the busting of unions representing teachers and other school personnel. The right is aiming at resegregating public schools by race and income level via various privatization and voucher schemes. And of course, there is an electoral strategy behind this too: it is a ploy to pump up the social base of the increasingly Trumpized social base of the right-wing Republican forces for the midterms and beyond.

This: The astroturf “parents’” organizations that the ruling class has recruited as the attack squads in this struggle are like the worst actual teachers one could imagine. And the teachers they are attacking are the best there are, which is why they are attacking them. This attack also is linked to agendas of school privatization and the busting of unions representing teachers and other school personnel. The right is aiming at resegregating public schools by race and income level via various privatization and voucher schemes. And of course, there is an electoral strategy behind this too: it is a ploy to pump up the social base of the increasingly Trumpized social base of the right-wing Republican forces for the midterms and beyond.

They consider their own children to be helpless idiots who know nothing themselves, and who have to be filled with traditionalist propaganda and prevented from learning anything new that does not conform to the bigoted and unscientific attitudes they themselves hold. In the words of Virginia State Senator Amanda Chase (R-Lunatic Fringe, Va.), “My children belong to me.” Evidently Senator Chase does not regard her children as human beings with rights, interests, and minds of their own (and does she know about the Thirteenth Amendment?).

Feeling “uncomfortable” is essential to the learning process.

They profess to be protecting their children from anything that might make them “uncomfortable,” but frequently feeling “uncomfortable” is essential to the learning process, because it makes one think, inquire, question. Finding out what was the real state of affairs in South Africa made me feel uncomfortable. Finding out what lies I had been taught about U.S. history and society made me uncomfortable. Finding out how Native American people felt about white scholars who study them made me super uncomfortable, since at the time I was a white scholar doing exactly that.

All this discomfort caused me to study, ask questions, listen, be critical and self-critical, and, most important of all, to act. After all this discomfort I could never go back to being a simple academic careerist. It was good discomfort, helpful discomfort, liberating discomfort, and the only thing I regret is that it did not befall me much earlier when I was a child in South Africa.

This discomfort set me on a path of activism, a major step of which was to join the Communist Party USA in November 1987, a step I have never regretted.

The alleged “discomfort” from which these reactionary parents wish to protect their children would come from realizing that this country has a racist, classist, sexist, and homophobic history which has permeated institutional structures and still holds many people back today. These parents also feel discomfort about new ideas on sex and gender, because they were always told the Biblical version that a man is a man and a woman is a woman, and there are no further complications to the issue. No matter that the developing scientific understanding of sexuality and gender tells quite a different tale. When science and bigotry clash, it is science that must be rejected.

This is the kind of discomfort that Virginia’s ultra-reactionary governor, Glenn Youngkin, says he wants to protect children from. He and his ilk are inciting people precisely against the best teaching, the liberating teaching, the teaching that builds human beings who are knowledgeable, empathetic, and socially responsible.

Fortunately, children are indeed not “empty vessels” but have their own capacity to think and inquire. And they do: among friends, on social media and the internet, you name it. They do gather information in their own circles, and they will continue to do so, and my prediction is that the children of some of the most fanatical allies of Youngkin and his ilk will rebel against their parents and the backward, inhumane things that they profess.

That’s what has always happened in the past, and it represents a brighter future.

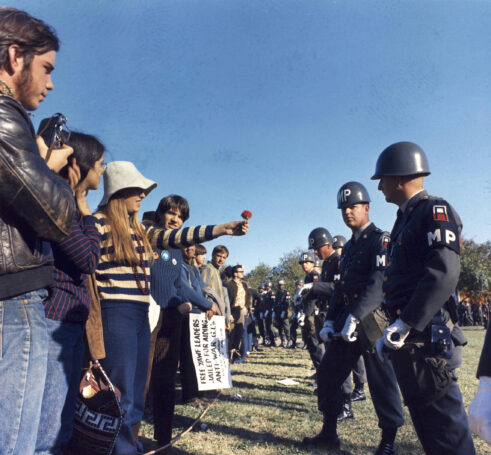

Images: Alliance for Excellent Education (CC BY-NC 2.0); Anti–critical race theory speaker, Anthony Crider (CC BY 2.0); Anti-integrationists in Little Rock, John T. Bledsoe, Wikipedia (public domain); Apartheid in South Africa, Initials BB (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Vietnam War protest,

Join Now

Join Now