In 2008, Nick Taylor wrote a fine narrative history, American Made: The Enduring History of the WPA: When FDR put the Nation to Work (2008). His conclusions remain relevant today:

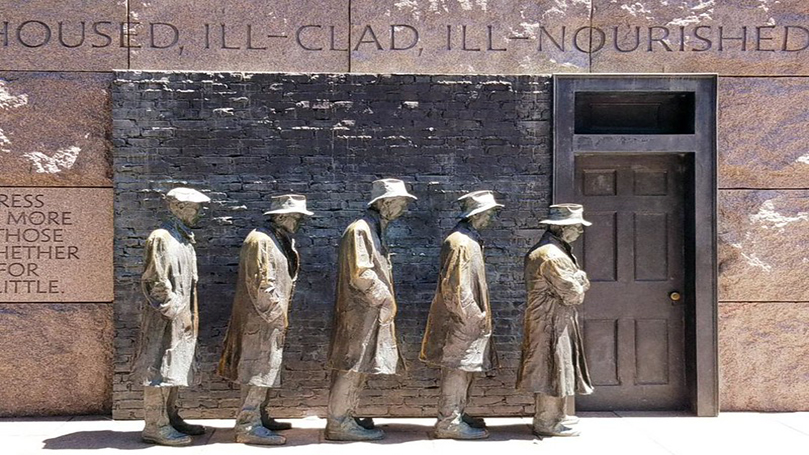

Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins believed that people given a job to do would do it well, and the fact that their paychecks were issued by the government would not make a whit of difference. They were right. . . . The workers of the WPA excelled. They shone. They created works that even without restoration have lasted for more than seventy years, art that is admired, research that is relied upon, infrastructure that endures. They clothed the threadbare, fed the hungry, taught the illiterate, inoculated the vulnerable. They turned toys that were rich children’s discards into poor children’s treasures. They fought floods and hurricanes and forest fires with bravery. (p. 530)

Taylor doubted that a policy on the level of the WPA (Works Progress Administration) was possible in the America of 2008, but then history in the form of the stock market crash, foreclosure crisis, and victory of Barack Obama intervened to lead many see a “new New Deal” — what Obama called “change we can believe” — possible after nearly three decades of Reagan-Clinton-Bush policies away from the old New Deal.

It didn’t happen for many reasons, as today we fight against the most reactionary and corrupt president and administration in history. But it can and must happen if we are to overcome the greatest U.S. and global crisis since the Great Depression and World War II. What came to be called the “3 Rs” in the depression — relief, recovery, and reform — are needed again today.

Taylor’s work had one enormous hole, which this article will hopefully fill. Stilled trapped in cold war anti-Communist ideology, he portrayed CPUSA activists (whom he called “Stalinists” in traditional anti-Communist language) and their left opponents (“Trotskyists”) as engaged in ideological wars with each other, writing in pamphlets and their press about policy but not having any serious impact on the development of the New Deal’s social policies. Instead he saw leaders, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins particularly, as playing the decisive role in the development of the WPA and other social legislation.

Without understanding both the mass upsurge of working people in the period, the creation of what became a center-left coalition at the grassroots in organizing, educating, and coordinating the struggles of the coalition, the establishment of the WPA and agencies like the NLRB, the Farm Security Administration, and programs like minimum wages and the food stamp plan can’t really be understood. The absence of such a left and especially a strong and growing Communist Party or its equivalent acting as its vanguard was a central reason the Obama administration failed to implement a new New Deal. In this article I will attempt to make those connections.

The Works Progress Administration

In its eight years of existence the WPA would employ over 8 million working people, most of whom were unskilled and semi-skilled men, the great majority with families. Its initial budget was in real dollars the largest peacetime appropriation in American history, nearly 7% of the 1935 GDP. And it was a major part, along with the National Labor Relations Act and Social Security Acts of 1935, of what historians call the “second New Deal.” More accurately, these policies and others which would be developed over the next three years might be called the “Left New Deal” or, as W. E. B. Du Bois would say at the University of Wisconsin in 1960 before his departure to Ghana and his formally joining the CPUSA, the “surge toward socialism” that characterized the mass struggles of the 1930s.

CPUSA activists were the most important organized force in developing that “surge to socialism,” of which the WPA was an important part. Beginning in 1930, Communists organized Unemployed Councils throughout the nation to demand jobs while the capitalist class and its press was largely denying the severity of the depression. Communist-led groups blocked evictions, held demonstrations including sit-ins at city halls, and fought for “work relief” (public jobs for the unemployed) and “home relief” (payments to those who could not work, primarily women with dependent children and the disabled).

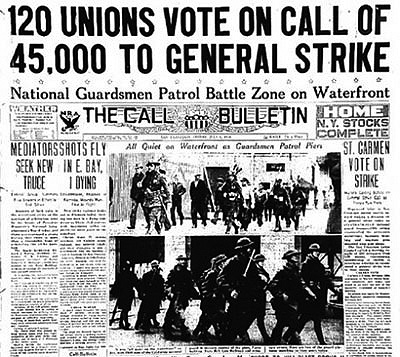

Although the Unemployed Councils’ most important contribution to the struggle was their development of the concept of unemployment insurance (which was also enacted in 1935), they were the most important group advancing a “work relief” program that the WPA embodied. A number of major strikes in 1934, most importantly the San Francisco General Strike, the first and only general strike in U.S. history which was successful, greatly increased the pressure on the Roosevelt administration to fulfill its 1932 promises of a New Deal for the people. Up to this point, the administration implemented state capitalist policies like the National Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which, while necessary, were attempts to stabilize the economy and bail out the capitalist class.

The capitalist class itself, which had adopted a wait-and-see attitude toward the Roosevelt administration, now mobilized a massive backlash against it. The American Liberty League, funded by the DuPonts and including major figures in the Republican and Democratic Parties, was founded to organize opposition to either have the administration use force to suppress the upsurge or find ways to oust the administration. Congress investigated accusations of a Wall Street–led plot using former Marine Corps General Smedley Butler to create a crisis through a march on Washington that would lead to Roosevelt’s overthrow and the formation of a military government. (Butler exposed this conspiracy, which was nipped in the bud, and figures in the Roosevelt administration believed that the aim of the plotters was to create widespread violence that would lead to the creation of a military government headed by General Douglass MacArthur, who two years earlier had suppressed the Veterans Bonus March on Washington, which had the support of progressive militants, the broad left, and the CPUSA.)

But the right-wing backlash failed decisively in the 1934 congressional elections, as pro–New Deal progressives increased their power in Congress. Meanwhile, the National Conference of Mayors in the fall of 1934 had called upon the president to come forward with a National Work Relief policy. The Conference was directly influenced by the unemployed councils, which were centered in cities, and some of the Conference’s staff members were (as its enemies would note) progressives supporting the councils and the CPUSA. For red baiters at the time and forever after, this was an example of “guilt by association.” For the rest of us, those who realize the importance of social legislation like the WPA, unemployment insurance, social security, protection for the right of unions to organize, minimum wages, etc., it should be seen today as a source of pride.

The importance of Harry Hopkins

As the WPA’s administrator, Roosevelt chose Harry Hopkins, long established as an activist social worker and organizer of social workers, an example of the center-left coalition that the New Deal became when at its best. Hopkins had a long history of fighting for the rights of the unemployed and the poor when he came to Washington in 1933 with Franklin Roosevelt. After graduating from Grinnell College in Iowa, he worked at Christadora House, a settlement house/community center on the lower East Side of New York. The poverty he saw would influence him for the rest of his life. He would continue his work in various activities, working with various philanthropic groups, serving as director of New York City’s Bureau of Child Welfare, and working for the Red Cross in New Orleans after World War I. Hopkins also helped draft the charter for the founding of the American Association of Social Workers and became its president in 1923.

Returning to New York, Hopkins worked in public health, directing the New York Tuberculosis Association and uniting it with the New York Heart Association. As the depression struck, Governor Franklin Roosevelt appointed him to direct the state’s temporary emergency relief administration and in 1933 its national equivalent, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

Although Hopkins had a tough and sometimes abrasive personality (some compared his public persona to the actor Humphrey Bogart at the time), he maintained the idealistic values of the social worker.[1] Influenced also in his youth by Social Gospel (progressive) Christianity and Christian Socialism, Hopkins wrote, “The chief thing in this life to my mind is to work toward the founding of an ideal state, in this earth, based on social justice which will make for happiness for us all.” Hopkins also understood practical and organizational politics, a necessity for administering the WPA.

The WPA literally changed the face of the United States. It built over 1 million kilometers of roads, over 10,00 bridges, as well as public parks, airports, and public housing. It worked with other agencies, including the Tennessee Valley Authority to develop public power for the “third of a nation” without electricity, mostly poor rural areas where electrification was not profitable for private companies. Its infrastructure projects included 40,000 new and 85,000 improved buildings. These new buildings included 5,900 schools; 9,300 auditoriums, gyms, and recreational buildings; 1,000 libraries; 7,000 dormitories; and 900 armories. There were also 2,302 stadiums, grandstands, and bleachers; 52 fairgrounds and rodeo grounds; 1,686 parks covering 75,152 acres; 3,185 playgrounds; 3,026 athletic fields; 805 swimming pools; 1,817 handball courts; 10,070 tennis courts; 2,261 horseshoe pits; 1,101 ice-skating areas; 138 outdoor theatres; 254 golf courses; and 65 ski jumps. From the humble sidewalk to the Griffith Observatory (below), construction projects popped up everywhere.

And it spent billions in today’s dollars to renovate and develop public utilities, constructed 20,000 miles of water mains, and renovated and built firehouses.

It also advanced conservation in the form of flood control and fire prevention. Educational programs to aid local authorities and citizens in avoiding destructive environmental policies were also important parts of the WPA’s work. Left activists, Communists especially, in the Workers Alliance, acted as a kind of informal “union in the WPA.”

The WPA’s cultural and educational work: A short list

Denounced as “un-American” by enemies of the WPA, the various federal arts and humanities projects explored the history of the United States and of its diverse peoples as never before. The WPA Federal Music Project organized community symphony orchestras playing a wide variety of music and employed musicians to both perform and provide free music lessons to people and develop music appreciation programs. It provided work at its peak for over 16,000 musicians and encouraged both adults and children to “learn by doing” (what was and is the great idea of progressive education), that is, to both hear music and play musical instruments. The Music Project also became an important center for the preservation and dissemination of non-commercial “folk music,” grassroots songs and melodies which often expressed working-class social struggles.

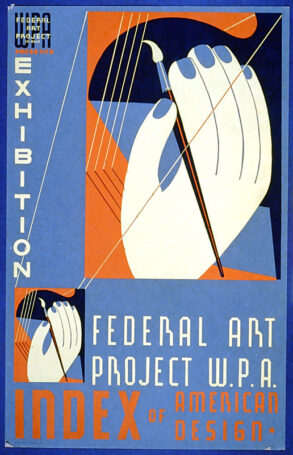

The WPA Federal Arts Project also advanced the principle of “learning by doing”: teaching drawing, painting, clay modeling, wood carving, and arts and craft skills and other artist skills for citizens, and establishing exhibitions of WPA Art Project work, some with clear class struggle, pro-labor, anti-racist, and anti-fascist messages. Some of these public artworks were vandalized by organized right-wing groups and later removed or whitewashed over in the Cold War political climate. The Project employed and nurtured artists ranging from African American realist painter Jacob Lawrence to the abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, along with socialist-oriented painters Ben Shawn and Stuart Davis.

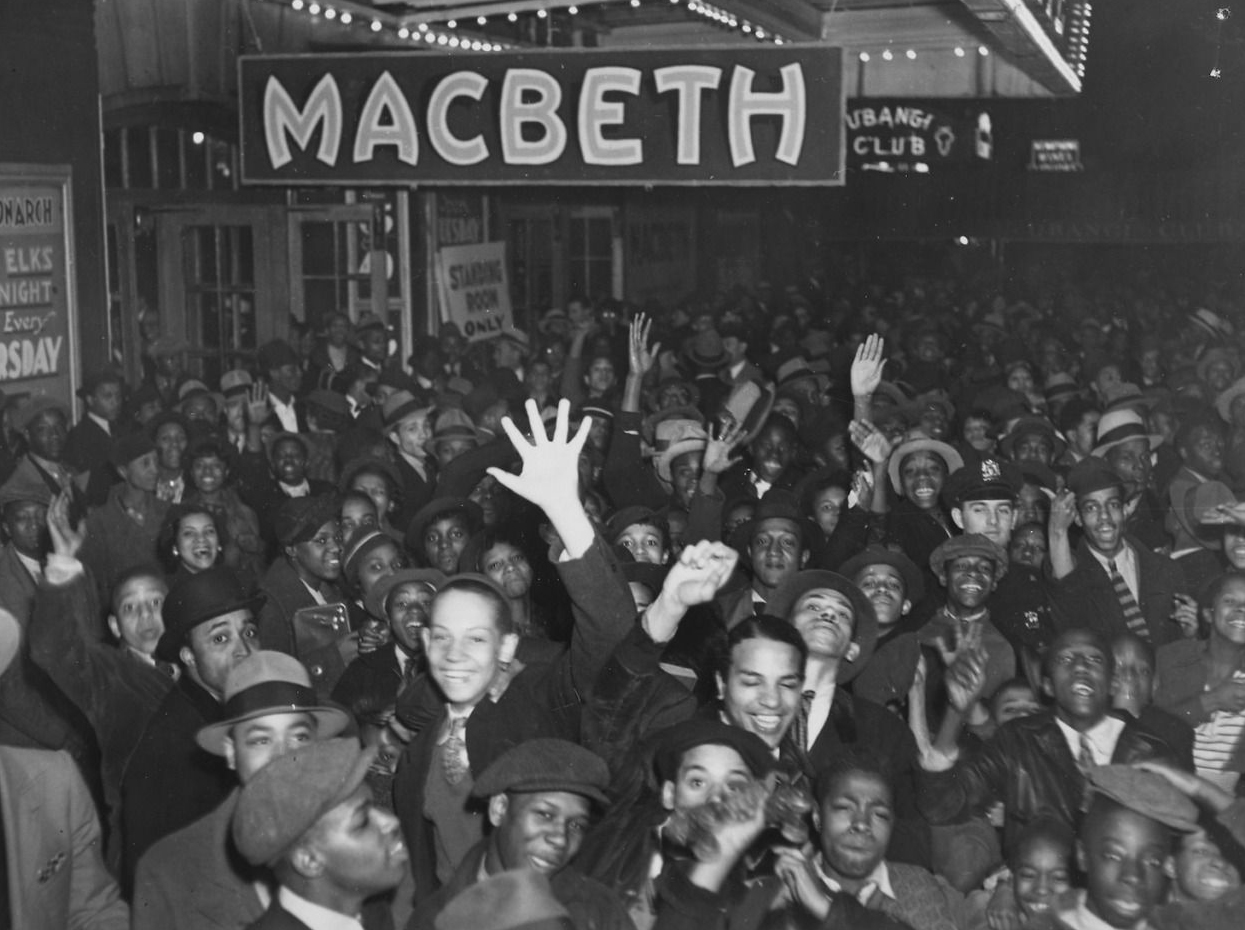

The Federal Theater Project, directed by Hallie Flanagan, a Vassar professor, became the most controversial of WPA education projects. Its “Living Newspaper” groups reached millions of people with skit presentations of the news of the day from an anti-fascist, anti-racist, pro-labor outlook. Young activists, including YCL and Southern Negro Youth Congress members, were involved in these grassroots presentations, which challenged via theater the overwhelmingly conservative anti–New Deal press.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) — led by the Texas racist conservative Democrat Martin Dies and established by conservative coalition forces in Congress to provide a federal red-baiting center for attacks on the trade union movement and New Deal agencies — denounced the Federal Theater and all of the WPA’s education programs for advancing anti-segregation and anti-“free enterprise” work, both of which showed Communist influence in the administration.[2] Following the 1938 elections, where conservative coalition politicians made significant gains thanks to the recession, the budget for the Federal Theater was eliminated. In its attacks, HUAC said that “racial equality forms a vital part of the Communist dictatorship and practices.” What HUAC was saying openly was that racist policy was an essential part of “American freedom,” which lives on today in the racist rhetoric of the Trump administration and its crude attempts to defund or eliminate entirely institutional safeguards against racism developed over the last 60 years.

While racism often reared its ugly head in the WPA and other New Deal agencies, thanks to the role of the Southern Democrats and Southern states, the WPA generally as it developed provided more jobs and more training and education for African Americans, overcoming in its last years the suspicion and hostility of the NAACP and other civil rights activists who came to support it.

The Federal Theater Project, through its Negro Theater Units (the most famous of which were two theaters in New York, but which had units in 22 cities), provided education for aspiring Black actors and others in theater arts. Some of the Project’s most famous performances (including a Voodoo version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth set in Haiti) were examples of this achievement. The Federal Theater also acted to fire, in a number of cases, project managers who sought to practice segregation in various theater projects or expressed racist attitudes toward Black workers. Many actors, writers, director, composers, and fine artists (far too numerous to mention) went on from their work in the WPA to make major contributions to U.S. and global culture.

Finally, the WPA Federal Writers Project also played an important role in providing both guidebooks for American towns, cities, and regions and historical accounts of the nation’s diverse peoples. The project also established an oral history project which archived the voices of men and women born into slavery, a history that generations had sought to erase. The WPA’s Historical Records Project also employed researchers to collect and catalogue documents that would enable scholars and citizens to understand their nation.

The deforming effects of institutional/ideological/systemic racism

Racism and segregation were a significant part of the WPA and other New Deal agencies, despite the opposition of prominent New Deal officials. It was, to paraphrase Karl Marx, “the dead hand” of American history, rising to build barriers against social progress, as it had since the colonial period and continues to do today. The State Department, for example, not a New Deal stronghold, strenuously objected to a Negro Theater portrayal of Mussolini’s murderous invasion of Ethiopia and had it stopped.

And red-baiting political attacks from the conservative press and politicians had their effects. Marc Blitzstein’s operetta The Cradle Will Rock, inspired directly by the work of Communist activists, was cancelled by Washington, leading to a famous walk-out led by Orson Welles of cast and audience and an impromptu one-time performance at another theatre.

But the argument that New Deal policies themselves strengthened segregation, which has become fashionable in certain sections of the left and has been used by the right in recent years, simply doesn’t hold water. Segregation didn’t have to be strengthened. Business with the support of local state and federal government made it systematic and brutal. The belief that Blacks and other people of color were somehow harmed by legislation, agencies, and policies which began to address even in a limited way institutional and ideological racism makes no sense. The National Negro Congress and the Southern Negro Youth Congress, two national organizations which the CPUSA helped create, understood this and mobilized support for the WPA and other New Deal programs, while challenging the racism they found in these programs.

In the 21st century, the hopes for a “new new deal” which energized the Obama campaign and today’s hopes for a “green New Deal” reflect the reality that the New Deal legacy remains a foundation for an American future. A new deal, in which higher levels of economic and social equality are achieved through planning by a viable and vital public sector — what people throughout the world see as the substance of socialism — can be a reality.

Notes

[1] He had belonged briefly to the Socialist Party before WWI, and after the fall of the Soviet Union “documents” were produced so show that he was a “Soviet agent.” Actually, if all those who were accused of being Soviet agents really were (and the charges were manufactured), the Soviets can be credited for contributing enormously to the welfare of the American people.

[2] The overwhelming conservative press continually attacked the WPA as a refuge for lazy, unproductive people at the expense of tax payers, sarcastically calling it “We Poke Along” and “We Piddle Along.” Hopkins answered them powerfully when he said at a New Deal rally in 1936: “The things they have actually accomplished all over America should be an inspiration to every reasonable person and an everlasting answer to all the grievous insults that have been heaped on the heads of the unemployed.”

Images: Top, Roosevelt memorial, photo by Mike Licht (CC BY 2.0); Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles, photo by Matthew Field (CC BY 2.5); Poster advertizing art exhibit, photo by James Vaughan (CC BY-NC-SA 2.o); Federal Theatre Project, Macbeth, Library of Congress (no known copyright).

Join Now

Join Now