This article is part of a series on Communist educators, a project of the CPUSA Labor Commission Educators Subcommittee. Click here for more.

One generation removed from slavery, encompassing a journey from rural poverty to urban hardship, Williana Burroughs was a teacher, housing organizer, internationalist, and radical Black intellectual that consistently challenged the ruling class. Her revolutionary commitment to the struggle for equality led her to become the first Black woman to address the Comintern.

Burroughs was born as Williana Jones on January 2, 1882, in Petersburg, Virginia, to formerly enslaved parents. Her father passed away when she was four years old. Her mother then moved the family — including Burroughs (then called “Liana”), her sister Nelly, and her brother Gordon — to New York City.

Burroughs was born as Williana Jones on January 2, 1882, in Petersburg, Virginia, to formerly enslaved parents. Her father passed away when she was four years old. Her mother then moved the family — including Burroughs (then called “Liana”), her sister Nelly, and her brother Gordon — to New York City.

Her mother worked as a cook, earning poverty wages that couldn’t fully support the family. Because her mother couldn’t work in someone’s kitchen and care for her children at the same time — and because she often needed to take “sleeping-in” jobs — the young Liana and her siblings were sent to the Colored Orphan Asylum in Harlem. They lived there from the time she was four years old until she was 11, when her mother had a “sleeping-out” job.

Jones (still Burroughs’ last name at that time) attended public school in New York before graduating from Normal College, now known as Hunter College. Simultaneously working as an assistant to her mother and helping take care of her younger siblings, she was the only Black student in her class of about 50 and graduated near the top. One classmate described Jones as someone “not afraid to state her own convictions … what is more, she’ll stick to them, at any time and under any circumstances.”

Educator and intellectual

In 1903, she began teaching first grade in New York City public schools. Working with mostly poor, Black, and immigrant students helped develop her political consciousness.

Burroughs began to seek the best way to fight against the oppression of her people. When asked why she didn’t join a Labor Party, she replied that the Jim Crow attitude of the Socialist Party repelled her. “I knew enough to want to join something, but I also knew enough not to join the Socialist Party,” she would comment later. “They had one policy on the Negro question in the South and another, much pinker, policy in the north.”

In 1909, she married her husband Charles Burroughs and was subsequently pushed out of teaching in New York City due to a marriage bar. She went on to work briefly as a social worker, which deepened her political development. After the marriage bar was lifted, Burroughs returned to teaching in Queens in 1925, and soon joined the radical New York City Teachers Union (TU).

It was through the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC) that Burroughs eventually joined the party in 1926. Burroughs was looking for a “club of juvenile radicals” to involve her children in. When someone “warned” her, “They say it isn’t Communist, but I say it is,” she joined up and began teaching classes on the history of African Americans. “But that wasn’t enough,” she said. “I wanted to get closer to the real struggle, closer to the basic organization of the working class in which I belong. I joined the Communist Party.”

Organizing for revolution

Writing under the pen name “Mary Adams,” Burroughs published influential articles such as her “Record of Revolts in Negro Workers’ Past,” published in the 1928 May Day addition of the Daily Worker. The text outlined Black resistance aboard slave ships, the Underground Railroad and resistance to slavery throughout the Caribbean, including the legacy of the Haitian Revolution.

In 1928, she traveled to Moscow with her children, ten-year-old Charles and seven-year-old Neal, to represent the ANLC at the Communist International’s Sixth World Congress. At the Congress, Burroughs called for a better examination of the importance of women’s work and Black women’s issues by the international Communist movement.

She urged the CPUSA to develop top level Black leadership within the party and devote more efforts and resources toward organizing the rural South and Black communities in the North. Success in this, Burroughs said, would depend on organizing Black women, West Indian and African immigrants, youth, and the unemployed. She argued it would also require developing the party’s links with anti-imperialist struggles throughout the Caribbean. A few years later, James W. Ford would be elected to the CPUSA Political Bureau and nominated as its candidate for Vice President, running on the ticket with William Z. Foster.

During her visit to the Soviet Union, Burroughs visited a number of schools and summer camps in the Soviet Union and decided to place her children in school there.

Back in the U.S., Burroughs began organizing with the Harlem Tenant’s League. The League fought against poor housing conditions that caused high death rates among Black residents. Together with other organizers, she mobilized hundreds of Black women in the community, helping to build coalitions between Communists, churches, and community members. They organized rent strikes, demonstrations, and actions to block evictions. Their demands for improved and desegregated housing she connected with the larger struggle against capitalism.

In Harlem, Burroughs worked closely with Louise Thompson Patterson on the campaign to defend the Scottsboro nine. There was a major push on behalf of the Communist Party and the African American freedom movement to publicize and internationalize the issue of these nine Black teens falsely accused of raping two white women.

At that time, she also became active as a teacher with the Teachers’ Committee for Defense of Salaries. When a fellow teacher, Isidore Blumberg, was expelled in retaliation against his role as chairman of the salary committee, Burroughs chaired the Blumberg Defense Committee. She and her Comrade Isidore Begun led a large delegation of teachers to the school board to demand their fellow teacher’s reinstatement. When the president of the board, a Dr. Ryan, was unable to silence the them, he called the police and Burroughs and Begun were charged with “conduct unbecoming to a teacher and prejudicial to law and order.” The Board said that they “did wilfully interrupt the orderly proceedings…by demanding in a loud, boisterous and contumacious manner,” and suspended them without pay.

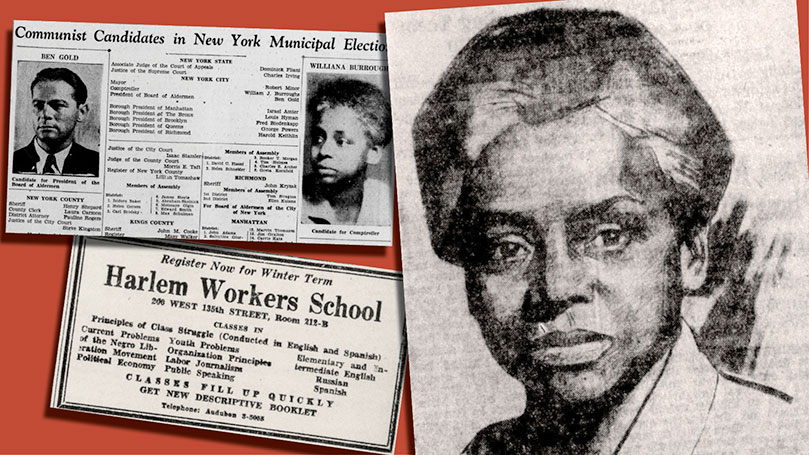

After being fired from teaching for the second time, she shifted her focus to Communist Party activities, working as an instructor at the Harlem Workers School. There, she taught and organized classes to activists and working class residents such as Principles of Class Struggle, Current Problems in the Negro Liberation Movement, Organization Principles, Public Speaking, and English language classes.

Taking her revolutionary politics into the electoral arena on the Communist Party ticket, Burroughs ran as the candidate for New York City Comptroller in the fall of 1933. When questioned whether she could “handle the job,” she replied, “Anyone who has run a household for four persons on $20 and has worked her way through college on $5 a month should be able to manage the financial affairs of a great city which has plenty of credit and resources. … That is, anyone who is in office under the control and in cooperation with a well-disciplined political party which has the interest of New York’s working class at heart.”

Though she did not win, she wound up receiving nearly 31,000 votes, the record number of votes received up until that point by any NYC Communist candidate. The following year, she ran for Lieutenant Governor of New York, continuing her efforts to bring Communist politics into the popular imagination.

Back in the U.S.S.R.

In 1937, following a recommendation from Communist Party leadership, Burroughs relocated to the Soviet Union to join the English language broadcast for Radio Moscow. There, she worked as an announcer and editor and became known as the “Voice of Moscow” to international listeners.

After almost a decade in the Soviet Union, she returned to the United States. J. Edgar Hoover had FBI agents waiting to detain her in New York City, but she evaded them by first sailing into Baltimore before traveling up to New York City.

Two months after her arrival, she passed away in the Manhattan home of her close friend and comrade, Hermina Huiswoud. Burroughs died on December 24th 1945, just one week before her 64th birthday.

Williana Burroughs brought the Black freedom struggle together with the struggle for women’s equality, Pan-Africanism, and anti-colonial movements. She insisted that Black women be seen not merely as victims of capitalism, but as revolutionary subjects — central to the fight for a socialist future. Burroughs’ contributions helped strengthen the party’s work in bringing basic democratic questions to the forefront of the class struggle.

As she noted, “The misery, suffering and degree of exploitation under capitalism and in the colonies is very great. In spite of this, the women fight.”

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: 1. Newspaper clipping from The Daily Worker. Vol. 10 No. 232. September 27, 1933 showing Communist Candidates in New York Municipal Election (revolutionsnewsstand.com) / Williana Burroughs portrait by Morris J. Kallem (revolutionsnewsstand.com) / Newspaper clipping from Vol. 3 No. 3. July 7, 1934 edition of the Negro Liberator showing classes taught by Williana Burroughs at The Harlem Workers School (Ibid.). 2. Screenshot from May 1, 1934 edition of the Daily Worker 3. Photo of Williana Burroughs with her two sons (blackagendareport.com)

Join Now

Join Now