In the 1970s, a United Electrical Workers Union (U.E.) reporter and a friend of mine interviewed a rubber worker in Naugatuck, Connecticut. The worker’s son was killed in the U.S. War in Vietnam. The U.E. reporter asked what the worker thought of his relatively high wage and generally high standard of living. His response was crystal clear: What good is it. I don’t have my son.

I had forgotten that story until one day an old pamphlet fell from my desk bookcase. Its front cover was enticing. It depicted ancient sculptures with a smoking volcano backdrop. These were the remains of a Buddhist temple in Java, then part of the Dutch East Indies. Indonesia was also where most of the world’s raw rubber was extracted. (The 56% of rubber produced now is synthetic, dependent on dirty fossil fuel. Natural rubber is mostly plantation produced in Southern Asia.)

The U.S. capitalist class lionizes Charles Goodyear as the discoverer of usable rubber. He, through grit and accident, discovered that gum rubber plus sulfur plus heat led to a stable form of rubber. According to the account by the U.S. Rubber Company in The Romance of Rubber (1941), Goodyear lived through poverty, but the account reveals no details.

The facts are not pretty. Goodyear did have a family. They lived more than once in abandoned manufacturing plants. My count had him in debtor’s prisons three times. Napoleon III presented him with a special medal for his work, which he received while in the cell of yet another debtor’s prison, this time in France. He died in 1859 awash in debt. Capitalism doesn’t like people without money, and even less if you stiff them.

The Romance booklet opens with a section titled “A Peep into the Past.” To peep is to look through a small opening, and, as it turns out, the booklet offered a narrow opening into a classic example of ruling-class ideology.

The booklet credits Meso Americans for various uses of elastic latex from trees. It tells of Christopher Columbus describing bouncing balls. It leaves out Columbus’ enslaving and genocide of the Taino people in the Caribbean. Romance includes an idyllic drawing of a Native, in a tropical setting, handing a round object to a conquistador-type figure with a ship in the background. There is not a word of the brutality that followed.

In 1513, Núñez de Balboa, with 200 Spaniards and 600 natives, forayed into present-day Panama. They met hundreds of local natives armed with bows and arrows. The Indians had never seen guns and swords before. Balboa had his men open fire at point-blank range. Hundreds of natives were murdered; after all, gold was the objective and these natives were in the way.

Pizzaro was with Balboa and executed his own brand of genocide. In 1533, he went south into present-day Peru. He upped the ante and killed more than 7,000 Inka. He captured their leader Atahuallpa, promising to release him if gold was brought to him. The ransom was delivered. The gold filled a room 22 feet long, 17 feet wide, and 8 feet high. Pizzaro reneged on his promise and had Atahuallpa executed. (Readers who can tolerate this brutality should see the documentary Guns, Germs, and Steel based on the book by Jared Diamond.)

Natives fought back. For example, when sugar plantations were introduced on Hispaniola, now Dominican Republic and Haiti, escaped native workers came back out of the surrounding hills to burn domiciles and kill their enslavers. These battles and introduced diseases thinned the ranks of the natives. Our current encounter with Covid-19 gives us an idea just how fast an introduced disease can spread death through a population.

African slaves were introduced in the 1500s because the natives proved so unreliable, from the Spaniards’ point of view, and hostile. The new slaves quickly began joining their island native comrades in the mountains, forming the first maroon communities in the Americas. Their raids were so effective that sugar plantations were moved to the mainland.

Skipping three centuries forward, the brutality continued around the full-blown development of capitalism and its imperialist partners. Now it was the procurement, processing, and shipping of rubber, “black gold” in this case. In the U.S., Neville Craig dreamed of a railroad through the rainforests of Brazil to move rubber to coastal ships. A ship that launched from the U.S. in 1878 sank at sea with the loss of 80 workers’ lives. A replacement shipment of Italian workers was next. When workers realized that their low wages were being gulped up by the company store, they went on strike. Craig probably didn’t know there was a sizable contingent of anarchists among the workers.

Craig’s engineers created a huge steel cage out of the future train rails. They herded the workers into it at gunpoint. A deal was struck and the workers released, but soon they melted into the rainforest. Its dangers were preferred to exploitive work conditions and a gun-toting boss.

As the 20th century approached, capitalism was nurturing homegrown adherents. Peruvian Julio César Arana conducted his brand of brutal exploitation in the upper reaches of the rainforests in Colombia and Peru. He used thugs, aka “independent contractors,” brought in from Barbados to enslave five Indian nations. No one from the outside was allowed to see the whippings, torture, and murder it took to keep these natives generating the black gold.

That changed when Walter Hardenburg, the son of a U.S. farmer, stumbled on to this warren of brutality. He and a friend were beaten and imprisoned before they escaped. He vowed to expose Arana. Hardenburg made his way to England, as Arana had incorporated there. Responding to the inhumane charges, Arana claimed before his British board that he was “educating natives.” London send British diplomat and noted human rights activist Roger Casement to investigate.

Casement confirmed the brutality of Arana and his hired thugs. His activism was rewarded with a knighthood. But at the beginning of World War I, he sided with the Irish independence movement. His activism went a bit too far for British imperialists. While on trial, it was discovered that Casement was gay, which sealed his fate. He was stripped of his knighthood and hanged. (Much of this early history can be found in 1493 by Charles Mann.)

By 1912, the British decided rubber extraction and processing in Brazil was too messy and too expensive. They started plantations in Indonesia. The U.S. Rubber Company would take over with the waning of British, French, and Dutch imperialism. Thus the “romantic” depiction of an ancient Buddhist temple on the front cover of The Romance of Rubber.

What happened back in Brazil? It experienced the bust end of a capitalist boom. Manaus was one of those boom towns in the center of the Amazon. It was abandoned. Some fifty plus years later, I would drift into that same town. Manaus was sometimes referred to as the “rubber capital” of the world in its heyday. It was deep in the Brazilian rainforest. What was I doing there? It was 1969, and a friend and I were trying to figure out how to avoid the U.S. War in Vietnam, yet another imperialist incursion.

We were in one of capitalism’s classic boom/bust towns. Where there was once 120,000 people, there were now 20,000. We had no clue what we had drifted into. The vultures told us—literally. They seemed to know we were experiencing a dead carcass of capitalism. These secondary carnivores waddled behind us on foot down sidewalks as we passed many abandoned buildings. It had the feel of a funeral procession being stalked by unwanted mourners.

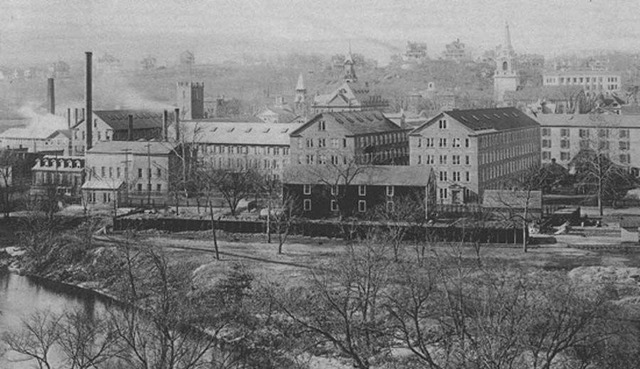

Little did I know at the time that in ten years I would experience another of capitalism’s boom/bust convulsions. In Naugatuck, Connecticut, rubber workers, in a coalition of five unions, went on strike. It was 1979.

Rubber shops along the Naugatuck River, Naugatuck, ca. early 1900s

The strike soon turned into a bosses’ lockout. The lockout morphed into a classic runaway shop. Thousands of workers were left unemployed by Uniroyal Company, which had taken over U.S. Rubber in 1961. Lenin’s classic definition of imperialism was being played out. Capital, that which produces profit, was being shipped out to various Asian countries.

Back in the Amazon, remnants of rubber tapping and rubber workers remained, and a mini-boom occurred during World War II. Japanese imperialism took over the rubber plantations in Asia. Henry Ford tried to cash in on black gold mania in Brazil by setting up a company town called Fordlandia. After 1945, though, it was right back to those Asian rubber plantations under the aegis of U.S. imperialism.

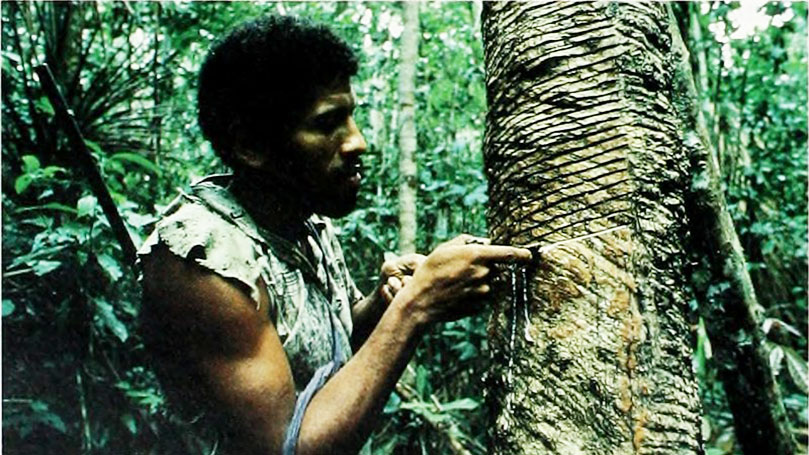

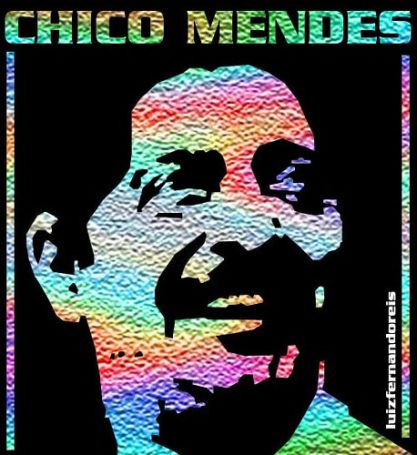

Brazilian rubber tappers, like workers all over the world, had drawn lessons from the capitalist plunder after the war. Under the leadership of Chico Mendes, a communist and a Workers’ Party member, they organized a union. They did not clear the forest in plantation manner. Instead, rubber workers practiced a sustainable form of tapping rubber trees in the midst of the incredibly diverse rainforest. They were natural allies of the environmental movement. Together, they proposed biosphere reserves. This didn’t go unnoticed by Brazilian ruling circles.

It was cattle ranchers who now had more than their eyes on the Amazon. They were egged on by the rapaciousness of the fast-food industries in developed countries. Ranchers began clearing rainforest. Just as the rubber barons did a century earlier, the ranchers hired armed thugs. A clash with the organized rubber tappers was on their agenda.

These ranchers learned from the assassinations of African American movement leaders in the United States such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. They had Chico Mendes, union and environmental organizer, in their sites; he was murdered by a shotgun blast near his forest home. He was the 90th rural leader killed in 1988.

Now it’s cell phones, Bluetooth, wide-screen TVs, and robotic cars. Like The Romance of Rubber shows in one industry, we’re experiencing what collective mental and physical labor can produce. But there is a veiled catch. The emphasis is on production forces and commodities. It has the appearance of progress. It dazzles. Capitalism does that.

But there is always its exploitive essence, which is the same across industries. Who owns and controls the land, the production process, working conditions, and extracts the profits—the production relations side is, quite often, hidden. The financial oligarchs behind the scenes and the exploitation of nature and workers become invisible, especially so if those workers are people of color.

On the other end of the boom/bust violence cycle in rubber was Naugatuck. The Romance of Rubber was distributed in the 1940s to workers, schools, and communities in the same Naugatuck of the worker whose son was killed in the U.S. War in Vietnam. It was the same Naugatuck that Uniroyal Company abruptly left in the early 1980s to superexploit workers in South Korea and the Philippines.

Capitalism also left a toxic landfill situated on a mountaintop in Naugatuck. The chemicals that were used in rubber production were now poisoning the very workers who toiled in those plants. A fight-back ensued led by a housewife. As in struggles everywhere, peoples’ leaders don’t go unnoticed. The owner of the landfill had his truck drivers harass the housewife at town meetings. The mayor, in the boss’s pocket, did the same. But lessons are learned more quickly these days. Protest mobilizations, which included student allies, were organized. The landfill was declared a Superfund site by the EPA. The corrupt mayor was sent to jail.

Naugatuck is now listed as a “distressed community” in Connecticut, especially due to double-digit unemployment. Its “distressed” environment should be included in that definition. Brownfields line the Naugatuck River. The town has ample fast-food restaurants and small nonunion shops where people bounce around between two and three part-time jobs.

Naugatuck has the largest number of military veterans in the state. It is easy prey for recruiters. The U.S. War in Vietnam claimed five lives here in a relatively small town.

Scott Hiley recently wrote, “The capitalist class has always depended on a liberal application of the stick to secure resources and labor-power on terms that allow it to maximize profits.” That stick can be blatant or a concealed weapon. Part of that weapon is ideology like The Romance of Rubber. Capitalist globalization applies exploitation, brutality, and fear on both ends of its global reach.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn spoke very plainly of capitalism at a May Day rally in the early 1960s: There is an “incompatibility of capitalism and human welfare.” She was chairwoman of the Communist Party of the United States.

That incompatibility, and fight-back, continue. Elections loom. Time to up the ante and go to work.

Digital art of Chico Mendes by Luiz Fernando Reis, Creative Commons (BY 2.0)

Cover image: “The Conservation Atlas of Tropical Forests,” Flikr, no known copyright.

Join Now

Join Now