Sing,

comrade,

sing

brother of the earth,

sing,

good father of fire,

sing for us all

– Pablo Neruda, Ode to Paul Robeson

When the towering 6’3 seventeen-year-old Paul Robeson arrived at Rutgers University in 1915, he was not only the sole Black student in attendance, but the third Black student since the school’s founding in 1766. A successful athlete in his youth, Robeson attracted the attention of Rutgers’ football coach. The team, however, pledged to quit if Robeson was admitted to the all-white team. After the team embarrassingly lost to Princeton, they allowed his admittance and instead resorted to doing their very best, within the confines of unsportsmanlike conduct, to kill him.

“On my first day of scrimmage … [o]ne boy slugged me in the face and smashed my nose … another boy got me with his knee … dislocating my right shoulder. Robeson recalled “a broken nose, a dislocated shoulder, a split lip, two swollen eyes and plenty of other cuts and bruises.” He was consigned to bed for a week and a half, but went on to make the All-American team twice.

As a Pan-African activist and militant labor advocate, Robeson wielded his voice for the exploited and oppressed, even when it jeopardized his career.

A similar situation played out in every field that Robeson came to dominate. In the theater, the concert halls, in movies, and in activism, reactionaries resorted to doing their very best, outside the confines of unsportsmanlike conduct, to kill him. As a Pan-African activist and militant labor advocate, Robeson wielded his voice for the exploited and oppressed, even when it jeopardized his career. Due to his unwavering progressive politics and worldwide fame, his passport was revoked in 1950. He was blacklisted and omitted from history books. Far from intimidating Robeson, this only made him more impassioned. Robeson wrote in his memoir, Here I Stand, “The artist must elect to fight for Freedom or for Slavery. I have made my choice.”

In college athletics, Robeson earned 12 letters in four different sports, was lauded by coaches, and was the first Rutgers player to make the All-American team twice in 1917 and 1918, praised as one of the greatest players of all time.

In the theater, he starred in over ten plays in the U.S. and England, starring in three Eugene O’Neill plays. He was also the first Black man to play Othello in almost a hundred years. Robeson would play the part for 296 performances between 1943-44, nearly doubling the previous record for Shakespeare plays on Broadway.

With his voice, he was the leading concert singer for much of the 1930s and 1940s, transforming “Negro spirituals” into an art form on concert stages across the world.

With his voice, he was the leading concert singer for much of the 1930s and 1940s, transforming “Negro spirituals” into an art form on concert stages across the world.

In film, Robeson played many roles, most famously singing Ol’ Man River in Showboat (1936), and sought roles that fought against racial stereotypes in both the U.S. and U.K. Robeson, in his own words, wanted to “dissillusion the world of the idea that the Negro is either a stupid fellow, as the Hollywood superfilms show him, or a superstitious savage under the spell of witch doctors.”

He was also active in labor and anti-fascist movements throughout his career. In 1946, Robeson led a delegation to demand that President Truman sponsor antilynching legislation. When he refused, Robeson told him plainly that Black Americans would resort to stopping the lynchings themselves. It was common for him to speak and sing at various meetings for WWII war relief groups, in union halls, for factory workers, and Republican fighters in Spain. In 1947, Robeson caused a stir by boldly singing the song that was never to be sung in the concert halls of Utah. At the University of Utah, he sang “Joe Hill”, a song commemorating the labor organizer who was controversially executed on false charges by a Utah firing squad decades earlier.

Two experiences set the course of Robeson’s political convictions. In 1934, Robeson passed through Nazi Germany on his way to the U.S.S.R. Robeson and his wife were abused and threatened by Nazi stormtroopers outside the Berlin railroad station. He was made brutally aware of the dangers of the spread of fascism. When he arrived in the U.S.S.R. hours later, however, he was welcomed by the Communist-led country with open arms. As he would later tell the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1956, “It was the first time I felt like a human being.” While in the U.S. and Nazi Germany, Robeson was abused and segregated. In the U.S.S.R., he was treated as a hero, celebrated in plays by Soviet playwrights and had a mountain summit in Central Asia named after him.

While he may have received a warmer welcome in the U.S.S.R., in the U.S., he was detested by white nationalists, as highlighted by the Peekskill riots, a violent affair resulting from racist backlash to two of Robeson’s performances. After his first performance was closed off by a right-wing mob, Robeson came back with thousands of supporters, union members, and veterans. Following the performance, violence erupted. Concert-goers fled while police and troops stood by and pulled over and ticketed attendees whose cars were damaged by rocks.

In 1950, Robeson’s passport was revoked, and in 1956, he was questioned before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Asked condescendingly why he didn’t move to the U.S.S.R., Robeson fired back: “Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I’m going to stay right here and have a part of it, just like you. And no fascist-minded people like you will drive me from it. Is that clear?”

During the McCarthy era, the blacklisted artist’s work dried up and his place in history was erased. Robeson’s name was curiously absent from historical accounts of the 1917 and 1918 All-American teams for decades. He’s absent in many Black history books and reference material, and has been undermined in the canon of Black history.

But this repression didn’t deter the towering American. On May 18, 1952, 30,000 Canadians came to hear Robeson sing at the U.S. border since his passport was revoked. Robeson remained politically and artistically active despite being blacklisted and forbidden to travel, continuing to connect Civil Rights and labor struggles. He wrote in his memoir, “The upholders of “states’ rights” against the Negro’s rights are at the same time supporters of the so-called ‘right-to-work’ laws against the rights of the trade unions.”

In 1958, after his passport was reinstated, following a decade of fighting to dismantle the blacklists, Robeson performed a sold-out show at Carnegie Hall and went on to perform throughout the world before his death in 1976. Robeson was one of the first Black Americans to reach his level of fame and did so with a level of political conviction and fearlessness that resulted in his being made a “non-person” by those in power. In his book Here I Stand, Robeson wrote, “Success in life was not to be measured in terms of money and personal advancement, but rather the goal must be the richest and highest development of one’s own potential,” an objective that he achieved despite immense repression.

Additional Reading:

Here I Stand, Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson: The Great Forerunner, Editors of Freedomways

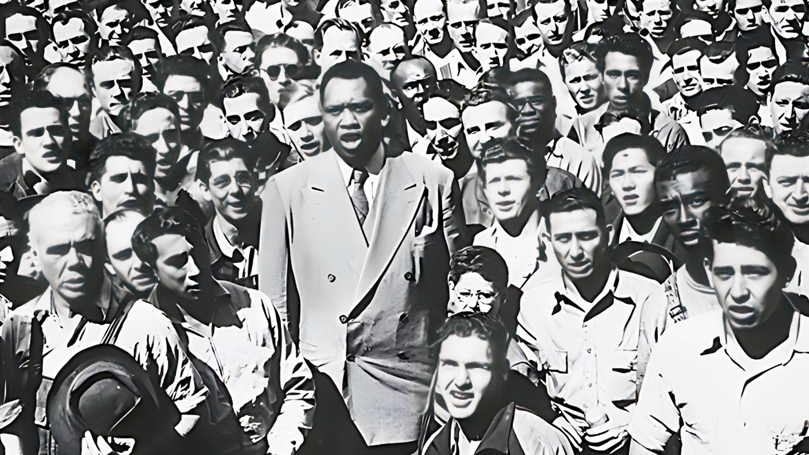

Images: Paul Robeson 1942 portrait by Gordon Parks, colorized using palette.fm (Library of Congress, public domain); Paul Robeson against lynching in 1946 by Addison N. Scurlock (via Washington Area Spark, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives Center, CC BY-NC 2.0); Paul Robeson with Shipyard Workers in WWII by pingnews.com from the National Archives (public domain)

Join Now

Join Now