A strong understanding of what historian Jurgen Kuczynski called the “laws of [fascism’s] emergence” requires a clear discussion of how fascism functions as a form of capitalist class rule. This essay delves into Marxism’s core analysis of fascism’s emergence, analyzing its class basis, the role of imperialism and monopoly capital, and some strategic concepts that inform our struggle against it. By unraveling the laws that underpin fascism’s rise, we gain the power to recognize its insidious approach and build a united front against its terror.

Laws of Fascism’s Emergence

To discuss the “laws of emergence” of fascism is not to accept the false notion that it is inevitable. Instead, the term “law” refers to the Marxist theory of a process — patterns of conditions that allow an object or phenomenon to come into existence and the internal contradictions that shape its potential development, or which may eradicate it.

Fascist rule develops over time, and once its grip is established, there is nearly zero free space for open struggle. From a revolutionary perspective, it calls for new forms of struggle and a fortified resistance to defeatism, or the belief that little can change for the better in current conditions. Fascism can be defeated.

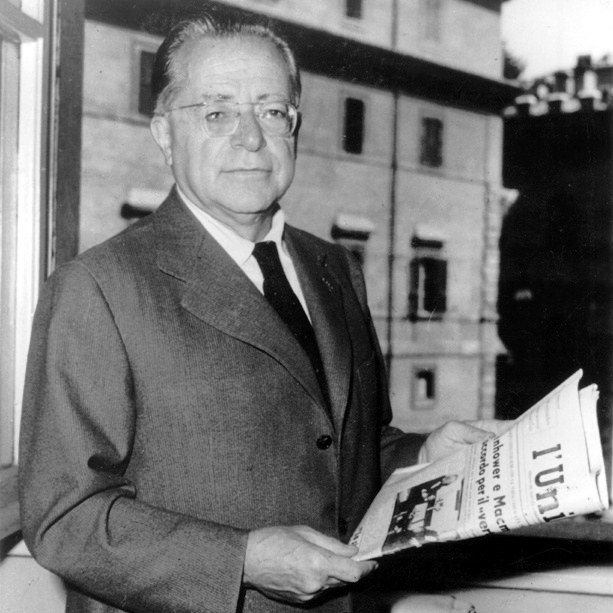

In the book Lectures on Fascism, Italian Communist Party leader Palmiro Togliatti notes two major errors made by Communists in the earliest stages of fascism’s European emergence. First was the German party’s idea that fascism was primarily, perhaps exclusively, a petty-bourgeois movement, party, and class formation. It was countered by the Italian party’s leadership which deployed a second error, the false equation of bourgeois democracy with fascism. (Both are dealt with in Lenin’s anti-fascist book Left-wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder.)

The first error underestimated monopoly capitalism’s role in fascism’s rise to power, its ruling mechanisms, and its political agenda. The second error, by incorrectly equating bourgeois democracy with fascist dictatorship, seemed to welcome fascism, mistakenly implying that an open dictatorship would promote direct confrontation with the bourgeoisie. Both fostered inaction or defeatism, even making excuses for the fascists and encouraging communists to wait out the battle. It also provoked sectarianism.

Thinking about Togliatti’s discussion of such errors emphasizes how similar thought patterns still exist. Today, some people incorrectly equate neoliberalism with fascism or say Biden is identical to Trump. Togliatti also alludes to errors that were made within the wider anti-fascist front: an incorrect belief in the inevitability of fascism as a stage of capitalism, that fascism would cure itself, or that it simply wasn’t any more dangerous than the usual bourgeois rule.

These errors recur today when fascistic threats loom for a host of reasons, not least of which is the difficulty of clear thought in dangerous times and an underdeveloped theoretical stance. Here, I sketch a Marxist analysis of fascism as a form of capitalist rule within a state linked to the imperialist world system.

Clarifications

To avoid these errors, Togliatti affirmed, “[f]ascism is the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic, most imperialist elements of finance capital.” He echoed the Comintern’s definition as part of its policy — the united front of working-class parties as the basis for a wider popular front against fascism and war. As part of the Communist Party USA’s program, it serves as a theoretical and practical anchor for its policies and program of action.

To clarify how it comes into existence, let’s explore some of these terms. For example, “dictatorship” is a class concept rather than an individualist one. U.S. media, politicians, and intellectuals often identify any socialist or communist national leader as a dictator, while describing their favorite fascists who support Washington’s or the IMF’s agenda as “strong leaders.” More precisely, dictatorship refers to a coalition of social forces that holds enough power for hegemony or the capacity, will, and ideological dominance to lead a class society. In this vein, the founders of what Gerald Horne calls the “slaveholder’s republic” established a dictatorship — though one opposed to monarchy and British rule.

To clarify how it comes into existence, let’s explore some of these terms. For example, “dictatorship” is a class concept rather than an individualist one. U.S. media, politicians, and intellectuals often identify any socialist or communist national leader as a dictator, while describing their favorite fascists who support Washington’s or the IMF’s agenda as “strong leaders.” More precisely, dictatorship refers to a coalition of social forces that holds enough power for hegemony or the capacity, will, and ideological dominance to lead a class society. In this vein, the founders of what Gerald Horne calls the “slaveholder’s republic” established a dictatorship — though one opposed to monarchy and British rule.

Marxists use the term dictatorship to name a “conjunctural” ruling bloc and the general character of class rule under a mode of production. It may refer to the general condition of bourgeois rule under any capitalism, as Marx and Engels did in the Communist Manifesto. It may also name working-class rule in a post-capitalist world, as did Lenin. Or it might refer to the more fragile and dynamic “form of rule” within a given era and historically specific national political unit. Antonio Gramsci’s term, hegemony (which literally means leadership), also designates the temporary, fragile dictatorship at the level of the “conjuncture.”

“Conjuncture” refers to the balance of social forces in a specific time and place. So, a discussion of the present conjuncture in the U.S. involves an analysis of the state, specific foreign policy, the labor uprising, various key democratic struggles, the conditions of the natural environment, an estimate of the power of the working class and its allies, and the like. (An example of conjunctural analysis can be found here.)

Three general ways of talking about capitalism are often used: 1) the capitalist mode of production, 2) stages of capitalist development, and 3) forms of capitalist rule. Indian Marxist Aijaz Ahmad reminds us that a “form of capitalist rule” is conceptually different from how we use the term “capitalist mode of production” or a specific “stage of capitalist development.” Rather, the form of capitalist rule in a conjuncture involves a political-ideological battle among competing social forces in a specific time and place.

At the most basic level, capitalism refers to a mode of production that historically began immediately prior to the so-called age of European exploration in the 1400s and continues in most of the world today. It generally refers to societies that developed three epoch-defining characteristics: 1) private forms of property as ideologically and legally primary, 2) the labor–capital relation generating surplus-value exploitation as a decisive feature, and 3) tied all people to commodity markets for survival. It unevenly succeeded feudalism and pre-dates socialism.

Marx’s (rough) modes of production

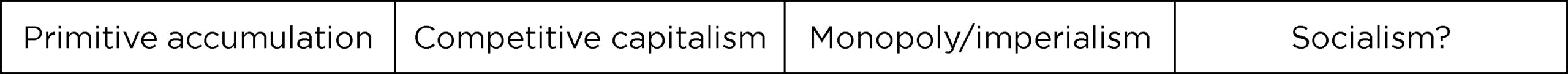

Within the penultimate mode of production are three major stages of capitalist development: 1) primitive accumulation, 2) competitive industrial capitalism, and 3) monopoly capitalism, or imperialism. A fourth, the transition to socialism, remains on the horizon. Simply put, when capitalism’s primitive accumulation stage was generally completed, competitive industrial development on a broad scale within a national political unit could occur. Industrialization saw the formation of multiple “capitals” become concentrated into singular capitals. After a period, driven by the spread of financial products (insurance schemes, debt/credit instruments, and stock, bond, and currency exchange markets), banking capital and industrial capital merged on a general scale, allowing monopoly power to dominate the political-ideological landscape. Thus, competitive capitalism transitioned into monopoly capitalism.

Each of these stages contains elements of the others and each sees contradictions that shape the transition to another stage of development in ways that are “inevitable,” or necessary, given the structure of capitalist-class relations. Today, because of assorted global struggles, we find ourselves in a crisis of monopoly capitalism (stage 3) and perhaps on a transitional threshold that leads into an early stage of socialist development (stage 4).

Capitalism’s stages of development

Togliatti writes that fascism is backed by “the most reactionary, most chauvinistic, most imperialist” section of finance capital. So how does this statement fit within the larger Marxist framework I’ve just described? And what does Togliatti mean by “the most” reactionary, chauvinist, and imperialist section of “finance capital”?

Let’s start with the latter two terms in the Togliatti quote. Togliatti reminds us that imperialism is a precise term that refers, unlike fascism (which is a form of rule), to a stage of capitalism itself. (See Lenin’s pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism and his book The Development of Capitalism in Russia.)

Much of that process in the U.S. took place during and immediately after the Civil War. Reconstruction’s promise of “abolition democracy” was delayed through terroristic violence, the suppression of democratic rights for Black farmers and agricultural laborers, and the restoration of capitalist class unity that established Jim Crow apartheid. (See the closing chapters of Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America for his assessment. Heatherton’s Arise! Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution documents how U.S. monopoly capital positioned workers, international trade, and the export of investment capital via the imperialist world system.)

Within this stage of monopoly capitalism, crises spiraled ever on. And a general crisis produced deepened levels of class struggle. In U.S. history, for example, new conjunctures demanded (from the capitalist’s perspective) new forms of capitalist class rule. Each form contained or constrained various working-class struggles: Fordism, New Deal-ism, and neoliberalism (see Ahmad’s reading of Gramsci).

Between each of these forms of capitalist rule, crises and struggles shaped the shift into the next. For example, 1873-1896 saw a general crisis of capitalist accumulation accompanied by massive social upheavals, including a nationwide uprising of workers and farmers. In his book Capital’s Terrorists, historian Chad Pearson shows that in the closing decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, capitalists sought to rule through a mixture of state and vigilante terror, targeting workers and labor unions through coordinated and organized attacks.

These conditions prepared the way for the Fordist concept. The Great Depression and all its anti-racist, class struggle content made the social democratic New Deal possible. Imperialism’s general crisis in the 1960s, accompanied by the collapse of direct colonialism and U.S. Jim Crow apartheid, set the stage for neoliberalism (a coordinated reversal of the New Deal). These developments offer no clear line of progress, and various technological factors, changing class compositions, geographical mobilities, and political-ideological factors shaped the outcomes.

Monopoly-imperialism’s forms of rule (U.S.)

Fascism as appeared in incipient forms during much of this time frame (consider the “Wall Street Putsch” conspiracy in 1933 against Franklin Roosevelt). Many capitalists see fascism as a form of rule that could delay the big transition over the threshold to the socialist stage of development.

Fascism’s class basis

As neoliberalism seems less capable of enabling efficient capital accumulation (due to growing struggles against racism, mass incarceration, generalized privatization, and climate crisis), more capitalists see the fascistic form as attractive. Our analysis of the class basis of fascist power begins, thus, by arguing that the organizing and financial basis of fascism is anchored in the monopoly capitalist class.

Imperialism and monopoly

Togliatti states that fascism’s emergence takes place only in a setting in which finance capital rules in the monopoly-imperialist stage of capitalist development. “You can’t know fascism if you don’t know imperialism,” he declared. It is the necessary condition under which fascism as a form of capitalist rule can materialize. The extremist wing of finance capitalism is always prepared to turn to fascism because it sees racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, religious repression, immigrant scapegoating, and provocation of hostilities on international scales as strategic methods of securing leadership of the ruling coalition.

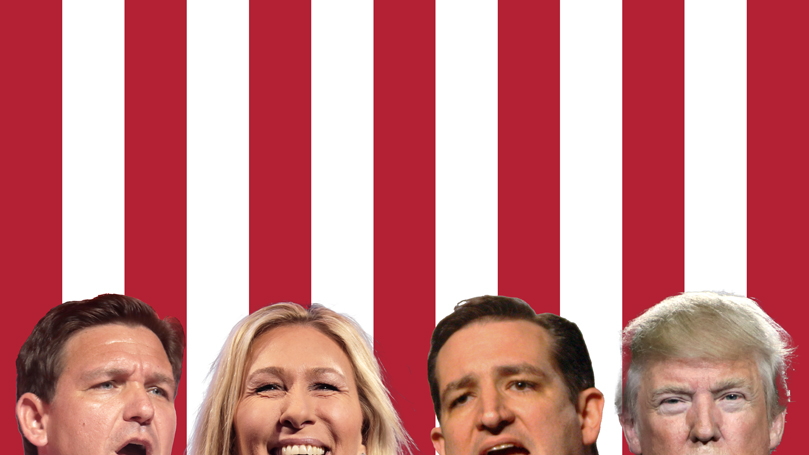

Fascist capitalists present an international face and inward domestic orientation. Dimitrov writes, “In foreign policy, fascism is jingoism in its most brutal form, fomenting bestial hatred of other nations.” Last May, Trump and other Republicans expressed this brutal jingoism when they demanded an attack on Mexico. Trump ordered his military campaign advisers to create battle plans. If Trump or another fascistic administration held power, they would try to carry out such plans using the vilest racist justifications to try to win support.

Do other ongoing U.S.-led global conflicts (e.g., over Taiwan, Ukraine, or NATO expansion) reflect a “jingoistic” or “bestial hatred”? Seven decades of deadly U.S. imperialist war have seen jingoism regularly featured. The peace movement’s consistent struggle over that period of time mobilized popular opinion against war and forced the imperialists to pretend democracy and human rights were the primary goals, denying the fascists the ability to use “bestial hatreds” to build their power. Today’s conflicts, including Cold War 2.0, give the fascists new opportunities for turning jingoism into a generalized form of ideological domination. Consequently, the broadest struggle against war and militarism holds definite anti-fascist implications.

“Vengeance” and the petty-bourgeois mass base

In his speech expressing the Comintern’s anti-fascist policy in 1935, Dimitrov stated, “Fascism is the power of finance capital itself. It is the organization of terrorist vengeance against the working class and the revolutionary section of the peasantry and intelligentsia.” What is meant here by “vengeance”?

Vengeance means to inflict retribution for an injury or a wrong. Why would the ruling class seek vengeance on the working class, especially its most revolutionary sections? The “laws of fascism’s emergence” include this feature: the ruling class’s revenge against a powerful revolutionary movement. It is more than simply an abstract anti-communism; it is a severe and systematic attack on revolutionary parties, social democratic parties, working-class militancy, and democratic organizing: assassinations, deportations, mass imprisonment, vigilantism, threats, and harassment.

Fascism in the 1920s, Gramsci noted, was the capitalist class’s response to the revolutionary war of maneuver, the uprisings led by the world’s communist parties and revolutionary coalitions conducted between 1917-1923. “War of maneuver” refers to the attempt to immediately seize power and replace the bourgeois dictatorship with a proletarian one. Revolutionary uprisings by the Bolsheviks in Russia, the Soviets in Hungary and Finland, the worker–peasant alliance in Sofia, the Spartacists in Munich, Turin’s factory councils, and Seattle’s general strikers were on Gramsci’s mind. We can add India’s anti-colonial struggles, Mexico’s revolutionary project, and Chinese worker and peasant uprisings.

Fascism in the 1920s, Gramsci noted, was the capitalist class’s response to the revolutionary war of maneuver, the uprisings led by the world’s communist parties and revolutionary coalitions conducted between 1917-1923. “War of maneuver” refers to the attempt to immediately seize power and replace the bourgeois dictatorship with a proletarian one. Revolutionary uprisings by the Bolsheviks in Russia, the Soviets in Hungary and Finland, the worker–peasant alliance in Sofia, the Spartacists in Munich, Turin’s factory councils, and Seattle’s general strikers were on Gramsci’s mind. We can add India’s anti-colonial struggles, Mexico’s revolutionary project, and Chinese worker and peasant uprisings.

Monopoly capital may control the fascists, but the movement’s mass base is largely drawn from the petty bourgeoisie, usually, but not exclusively, Euro-Americans. Dimitrov again: “[F]ascism has managed to gain the following of the mass of the petty bourgeoisie that has been dislocated by the crisis, and even of certain sections of the most backward strata of the proletariat. These would never have supported fascism if they had understood its real character and its true nature.” Parts of the petty bourgeoisie, disillusioned by economic crisis and experiencing a perceived loss of status, surrender to fascistic chauvinism. The corporate-backed “Tea Party” in 2010 was such a phenomenon. Many top Republicans today earned their stripes in that movement.

Finance capital offers the petty bourgeoisie no solutions to their problems, only emotional appeals to illusory power. Dimitrov and Togliatti insist that anti-racist working-class politics can appeal to parts of the petty bourgeoisie, through which they can learn to see finance capital as their class enemy, offering an empowering alliance with the multi-racial, multi-national working-class and democratic forces. Claims that fascist politics represent an uprising of workers, which we hear some so-called leftists spread today, echo the disastrous errors of the earliest assessments of fascism. It is a capitulation to fascist ideology.

Strategic concepts

The equation of all “forms of capitalist rule” with fascism — because they are all forms of capitalist rule — is a massive factual and strategic error. Dimitrov argued, “It would be a serious mistake to ignore this distinction [between liberal democracy and fascism], a mistake liable to prevent the revolutionary proletariat from mobilizing the widest strata of the working people of town and country for the struggle against the menace of the seizure of power by the fascists, and from taking advantage of the contradictions which exist in the camp of the bourgeoisie itself.” (This united front concept is addressed elsewhere.)

While amplifying key differences caused by the break between bourgeois democracy and fascism, continuities can also be observed. Dimitrov stated, “[I]t is a mistake, no less serious and dangerous, to underrate the importance, for the establishment of fascist dictatorship, of the reactionary measures of the bourgeoisie at present increasingly developing in bourgeois-democratic countries — measures which suppress the democratic liberties of the working people, falsify, and curtail the rights of parliament and intensify the repression of the revolutionary movement.”

Let’s pose the problem another way. By fighting against fascist rule, are we fighting for the continued existence of domination by less reactionary, less chauvinistic, less imperialist class forces?

The answer is a resounding no. A belief that it is, is a defeatist error, a strategic mistake, or a mishandling of facts. As Vijay Prashad affirms in his introduction to the Togliatti book, communists rejected the social democratic impulse “to deliver the working-class and the peasantry to the liberal wing of the bourgeoisie.” Instead, anti-fascist politics is about building a new force that can provide the working class and democratic allies with victories, causes for hope, and organizational capacities for power, ultimately transitioning the democratic question toward a struggle for working-class power. This transition is not automatic and has to be carefully organized.

Anti-fascism in the 1920s and 1930s led to a significant change in the Communist Party’s strategic theory and overall practice. If 1917-1923 represented a “war of maneuver,” the new terrain shifted generally to a “war of position” (the united front and popular front). A war of position signals a longer-term struggle to organize, educate, and mobilize an array of allied forces for the political transition to a new form of rule. Today’s political struggles may fit into the “position” category, but this doesn’t mean they will remain so.

Conclusion

Studying the “laws of fascism’s emergence” highlights the patterns, conditions, and contradictions that give rise to fascism as a form of capitalist class rule. It underscores the need for clarifying key terms to avoid common errors in analyzing fascism, particularly the misconception of equating fascism with other forms of capitalist rule. Fascism, rooted in monopoly capitalism and imperialism, seeks to consolidate power for the most reactionary elements of finance capital. It preys on the grievances of the petty bourgeoisie but remains fundamentally opposed to the interests of the working class and revolutionary movements.

Images: Flag of the United States (public domain) / Ron DeSantis by by Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0) / Marjorie Taylor Greene by Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0) / Ted Cruz by Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 3.0) / Donald Trump by Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0); Togliatti with a copy of l’Unità newspaper in the 1950s by unknown author (public domain); Haymarket affair by Harper’s Weekly, colorized using palette.fm (public domain); Tea Party rally to stop the 2010 health care reform bill by Fibonacci Blue (CC BY 2.0); CPUSA marching with Poor People’s Campaign by People’s World (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Join Now

Join Now