Many important figures in the history of the United States have been omitted from that history. Carter G. Woodson, the founder of what today is African American History Month, is certainly one of them.

Today we look at African American history in the midst of the triple crisis all people face — the Covid-19 pandemic, the loss of millions of jobs and income, and continuing dangers of “Trump fascism.” Yet we also look at African American history in the context of the hopes raised by the upsurge against racism in all of its forms represented by the Black Lives Matter movement and the defeat of both Trump in the presidential election and the Trump-incited coup of January 6. It is important to both remember Carter Woodson and learn from his life.

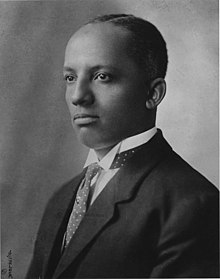

Carter G. Woodson, a pioneer student of African American history, started the concept of a Negro History Week in 1926, when Calvin Coolidge was president and the KKK was still a major force. At the time, what historians would later call “the tragic legend” of slavery and Reconstruction was taught in U.S. schools. In this dominant view, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had ended slavery, and both its history and the millions of slaves themselves could now be forgotten. The Southern whites were “victims” of corrupt and extremist politicians using violent, “savage” Blacks after the Civil War to gain wealth and power. The KKK had risen to defend and redeem the oppressed “white South,” as President Woodrow Wilson had said years before in both his writing on U.S. history and his praise for Birth of a Nation, the enormously popular film glorifying the first Klan of the Reconstruction period. A few years earlier the new mass Klan had launched a march on Washington without any criticism from President Calvin Coolidge (who left D.C. so as not to take any position on the Klan).

When the Lincoln Memorial was dedicated in 1922, organizers of the ceremony initially planned to ignore slavery and the Emancipation Proclamation and stress both Lincoln’s defense of the union and his sympathetic views toward the Southern states, a position supported by Lincoln’s surviving son, Robert Todd Lincoln. It took protests to compel the committee to invite prominent African Americans to the ceremony and to permit one major African American speaker.1

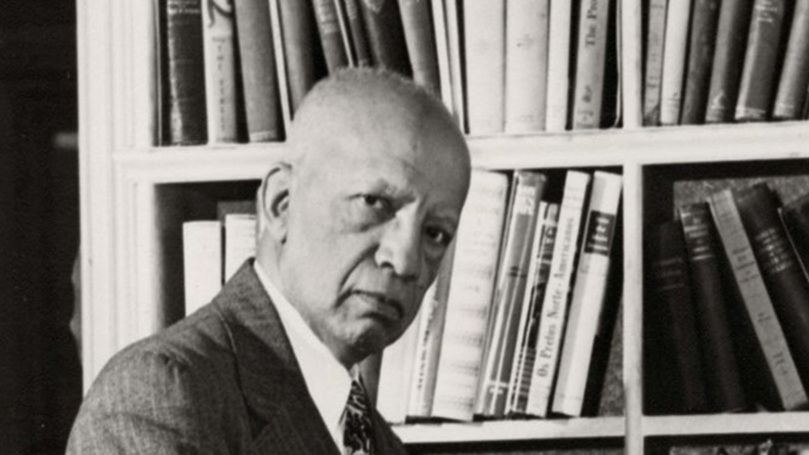

Woodson himself, a member of W. E. B. Du Bois’s generation, was a remarkable individual. Born in Virginia in 1875 as Reconstruction was ending in the defeat of those who fought to democratize the former Confederate slave states, Woodson was the son of former slaves who had aided General Grant’s army as they advanced against Robert E. Lee’s retreating Army of Northern Virginia in the final phase of the Civil War.

Woodson himself, a member of W. E. B. Du Bois’s generation, was a remarkable individual. Born in Virginia in 1875 as Reconstruction was ending in the defeat of those who fought to democratize the former Confederate slave states, Woodson was the son of former slaves who had aided General Grant’s army as they advanced against Robert E. Lee’s retreating Army of Northern Virginia in the final phase of the Civil War.

Woodson’s family moved to pro-Union West Virginia (created as a separate state after the war) when he was a boy. Finding work as a miner, he dedicated himself to achieving higher education. At the age of 20, he entered the segregated Frederick Douglass High School, earned his diploma in two years, and became a teacher. After earning a BA degree from Berea College in Kentucky in 1900, Woodson traveled to US-occupied Philippines and took a position as the principal of a high school there.

As was often true in colonial situations, individuals from working-class and minority backgrounds were given much greater opportunities in colonies than they were at home. In fact, Senator John Morgan of Alabama, a prominent Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee at the time of the U.S. seizure of the Philippines, wrote a memo to the State Department suggesting that the U.S. government resettle Blacks from the rural South and give them land taken from the Filipinos, land that had been promised to them but never received during the Reconstruction period.

Subsequently, Woodson was promoted to school supervisor in the Philippines, a position he held from 1903 to 1907. After his return to the U.S., Woodson earned a Master’s degree from the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. from Harvard, which, given the depth of the discrimination against African Americans in all forms of higher education at the time, were great achievements.

In 1915, Woodson co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which was a conscious response by African American intellectuals to the significant upsurge in racism in the U.S. during the Wilson administration. A year later, he founded the Journal of Negro History, which became the most important scholarly publication dealing with African American history for generations.

Woodson dedicated his life to the creation of what the early 20th-century writer Van Wyck Brooks called a usable past for both African Americans and European Americans. Through this work, Woodson sought to reject both the crude racist distortions and general omission of African Americans which dominated the broader narrative of U.S. history. No Marxist or communist, Woodson held and represented views of cultural pluralism and inclusion in a society whose establishment scholarship and media denied African Americans the right to be much of anything except to be part of the “Negro problem.”

As a scholar and active NAACP member, he communicated extensively with W. E. B. Du Bois, a founder of the NAACP and the premier African American scholar and intellectual of both his era and the entire 20th century. Woodson was also close with the West Indian–born radical Hubert Harrison and many others in the post–World War I African American and African Diaspora left.

In 1926, he established Negro History Week, hoping to mobilize both the African American press and sympathetic progressive media around the study of African American history. He chose February in which to celebrate this week because it was the birthday of both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. While Woodson did not follow in the path of Du Bois and Harrison, which led them as both theorists and activists to Marxism and the Communist movement, he saw them as both friends and allies in the struggle against racism.

Through the historical association he helped to found, Woodson encouraged the teaching and integration of African American history into public school curricula until his death in 1950. In addition, Woodson worked hard to direct the creation of an “Encyclopedia Africana,” which remained unfinished at the time of his death.

Woodson was a scholar first and foremost, not a political activist like Du Bois, Harrison, and others. Unfortunately, the developing Cold War at the time of his passing set back the struggle for African American equality in the short run and pushed back Woodson’s lifelong commitment to bring the study and teaching of African American history into higher education. Had he lived, Woodson would certainly have defended Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and other African American scholars, artists, trade union leaders, and political activists who faced imprisonment at worst and blacklisting from positions and occupations where they had long distinguished themselves.

Woodson was a scholar first and foremost, not a political activist like Du Bois, Harrison, and others. Unfortunately, the developing Cold War at the time of his passing set back the struggle for African American equality in the short run and pushed back Woodson’s lifelong commitment to bring the study and teaching of African American history into higher education. Had he lived, Woodson would certainly have defended Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and other African American scholars, artists, trade union leaders, and political activists who faced imprisonment at worst and blacklisting from positions and occupations where they had long distinguished themselves.

The Civil Rights movement, however, changed that. A new generation of scholar-activists urged that Negro History Week be turned into Black History Month in 1976 by the association Woodson helped to found (then called the Association for Afro-American Life and History). Today’s African American history month and African American studies programs in colleges and universities all over the country and the world, along with other ethnic studies and African Diaspora studies programs are a direct legacy of Woodson’s life-long work.

African American history month, despite objections to it by conservatives on the grounds that one group should not have a month dedicated to it, remains an important expression of cultural pluralism in the best sense. The history of African Americans, the rich and vital contributions that African American individuals, organizations, and the African American community have made to the labor movement, the struggle for civil rights, the arts, sciences and professions, and mass culture is necessary to understanding all of U.S. history. The national celebration of African American history month has helped to defeat the erroneous notion long expressed by conservative establishments that African Americans had no history beyond chattel slavery.

U.S. history is largely hollow without African American history, and African American history has no context and cannot be understood outside U.S. history. After the racist reaction of Donald Trump, whose use of history was no more than a crude expression of the “Big Lie” associated with Hitler fascism, understanding African American history is even more important if we are to both understand and advance U.S. society today and tomorrow.

Note

1. The plans for the opening of the Lincoln Memorial, at a time that the KKK was rapidly becoming a mass force in the U.S., highlighted the rampant racism of the period. No African American was initially invited to be part of the audience for the event. Protests led the committee to invite prominent African Americans, who were compelled under Washington law to sit in a segregated section. Segregation in public accommodations in D.C. remained the “law” until the post–WWII civil rights movements brought about desegregation. David Dinkins, an African American student at Howard University after WWII and later the mayor of New York City, remembered that he had to put on a turban and pretend to be a “foreigner in his own country to get a decent seat for a theater presentation.” Ironically, Robert Russo Moton, President of Tuskegee Institute, was the only Black person chosen to address the audience. Unlike the other speakers, he made a passionate plea for equal rights, which many journalists saw as the highlight of the event. Robert T. Lincoln, incidentally, who had traded on his father’s reputation to hold executive positions in both government and corporations, had, as a longtime director of the Pullman Company, who made the sleeping cars for the railroad lines and hired African Americans as “Pullman porters,” not only supported the company’s racist and anti-labor policies but also refused to meet with Du Bois before WWI to discuss those policies.

Note: Carter Woodson’s home in Washington, DC, designated a National Historic Site, is open to visitors (post-pandemic).

Images: top, National Park Service; Woodson in 1915, Wikipedia (public domain); statue, GPA Photo Archive (CC BY 2.0).

Join Now

Join Now