Eleanor, by David Michaelis, 2020, New York: Simon & Schuster

Eleanor Roosevelt, by Blanche Wiesen Cook, Volumes 1–3, 2016, New York: Penguin Books

In 1926 she joined a “mass picket demonstration” in support of striking paper-box makers. She was arrested, along with seven other “notable women” and charged with disorderly conduct (Cook, 1.363). She was Eleanor Roosevelt (ER).

In 1933 she became an activist First Lady and a tireless champion of the poor, workers, women, children, and African Americans. A 1935 headline read, “First Lady Tours Coal Mine in Ohio” (Cook, 2.262). She wore a miner’s cap and rode at the front of a mine train two miles down into the shaft where she watched miners at work. A cartoon in the New Yorker showed two miners looking up and exclaiming, “Here Comes Mrs. Roosevelt!”

The implication? ER, as activist, as First Lady, as compassionate human being, was everywhere.

Indeed, this “fierce warrior on the political battlefield” (Cook, 2.3) fought for reforms in jobs, health care, housing, recreation, education, child labor, consumer rights, housing, the status of women, worker rights, sex education, sanitation, public transit, school lunches, parks and playgrounds, unemployment insurance, and an end to lynching and racism.

That she was “everywhere” is remarkable, given her unpromising childhood. She was shamed and mocked by her mother as “a rather ugly little girl” (Michaelis, 6), as confirmed by a childhood playmate: “I don’t believe that her mother treated her as a human being at all” (18). David Michaelis gives us insight into ER’s insecurity: “The shame she carried shaped her relationships all her early life” (7), and throughout her life, “Eleanor believed that she had to earn love — by pleasing others” (28).

Her shame from her mother Anna’s critical eye may have been compounded by scandal regarding Elliot, her father. There were hints of childhood sexual abuse or incest, “hideous revelations . . . which supported the judgment that it was dangerous for Eleanor to be left alone with her father” (Michaelis, 24). And there was the shame of her father’s chemical dependency, inventoried by Michaelis as rum, tincture of opium, brandy, whiskey, morphine, laudanum, crème de menthe, champagne, and anisette, accompanied by delirium and blackouts. He “dried out” again and again in sanitariums but never remained sober for long. He died in 1894 at age 34 after falling from a window on 102nd Street in New York.

Two years prior, ER’s mother had died of diphtheria at age 29, so by 1894 ER was orphaned at age ten. Perhaps her own pain was a guiding force in her becoming a compassionate, humanist reformer who tried to bring simple decency to capitalism.

During her White House years, she spent “between sixteen and twenty hours a day running a parallel administration” (Cook, 2.30). Domestically, “nothing was beyond her range of interest,” and “little of significance was achieved without her input” (2.30). Edith Roosevelt, her uncle Theodore’s widow, famously dismissed Franklin as “nine-tenths mush and one-tenth Eleanor” (1.278). Yet she was called the First Lady of the World, “the most public, active, and popular of all U.S. first ladies” (3.544).

Her warmth was genuine and her sincerity “profound” (Cook, 1.17), prompting FDR to note that “anybody will tell Eleanor anything” because they trusted her. She had “a kind of generosity of the soul” (2.574), which led her to become “probably the most popular person in the country” (3. 355).

She was “among the world’s best loved women” because “no woman has ever so comforted the distressed — or distressed the comfortable” (Cook, 3.1). Michaelis notes that “American schoolchildren thought of her as a living saint” (491). One historian of the time suggested that “Negroes almost worshipped Eleanor Roosevelt,” and southern politicians hoped to capitalize on this by publishing photos of ER and African American college students with racist captions (336).

Journalist Martha Gellhorn looked to her as “something so rare that there’s no name for it, more than a saint, a saint who took on all the experiences of everyday life, an absolutely unfrightened self-less woman whose heart never went wrong” (Michaelis, 491). She is now included in “the pantheon of humanity’s demigods — Mohandas Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama” (491).

For her concern for American household workers or domestic servants ER was condemned as a radical. She argued that such workers deserve dignity, respect, and a living wage and benefits. Media reactionaries charged her with “ruining” America’s servants (Cook, 2.262), and bourgeois whites complained that “she ruined every maid we ever had” (2.255). As First Lady, “she upset race traditions, championed a New Deal for women, and . . . gave almost all her earnings to worthy causes” (2.3). A journalist noted, “She slaves away at writing, lecturing, broadcasting because she wants the money to give to those less able to earn” (3.356).

Her allies were “women who worked vigorously on the margins of politics,” since “the health of the state was considered women’s work” (Cook, 1.359). They tried to lessen the evils of “a wretched, mean-spirited society” (1.359). ER observed that “men played politics to win elections; women played politics because they sought to make things better for most people” (2.62). She declared that “women inspired all changes in human history,” so that “from epoch to epoch . . . women were in the vanguard of social change” (2.119). Clearly a feminist, she held White House press conferences every Monday morning for women journalists only (Cook, vol. 2).

What were the dialectical forces shaping ER’s political consciousness? She was born rich, a patrician, ruling-class bourgeois. She was confined to a supportive role as First Lady to FDR. Reactionary conservatives viciously and relentlessly attacked her humanitarian activism. And U.S. entry into WWII demanded her service to the war effort. Other forces led her toward activism. For example, the terrible poverty of the Great Depression certainly moved her, and the civil rights struggle inspired her.

She witnessed a working class that was active and vocal. In the 1930s “the American left reached its zenith” (Lipset and Marks, 230), with union membership at 3 million in 1927 and up to over 8 million (28.6% of the nonagricultural workforce) in 1939 (203). “The Depression, the great impact of class in politics, and the New Deal’s ‘social democratic tinge’ had helped produce a steady expansion in union membership, to 35% of the employed labor force by 1955” (235).

How did ER respond to such worker solidarity? As the author of a nationally syndicated newspaper column, she joined the American Newspaper Guild in 1936, to become the “first First Lady” to join a union (Cook, 2.424). She attended union meetings and honored picket lines, even refusing in 1939 “to cross one to attend FDR’s birthday ball at a Washington hotel where the waitresses were on strike for better daily wages” (2.425).

It is easy to love ER. But driving her devotion to the poor and working class was her fear of revolution. Cook observes: “ER worried that if peaceful change were not agreed to . . . the U.S. would suffer the revolutionary upheavals experienced by other nations” (2.132). Her compassion for capitalism’s victims was thus meant to prevent them rising up: “Not until poverty and injustice were dealt with, she insisted, would the revolutionary threat disappear” (1.243). ER cautioned that “justice and fair play do not breed revolutions” (1.244), and she also noted, “If we are not going to find remedies in Progressivism then I feel sure the next step will be socialism” (1.205). Her concern for others, while genuine and heartfelt, was meant “to redirect rapidly growing revolutionary sentiment” (2.86). She reminded that “unless there was dignity for all, there would be security for none” (2.188).

Ever the reformer, ER believed that capitalism could be “transformed into something humane” and, toward that goal, called for a ceiling or “strict limitation” on income (Cook, 2.212, 2.343). Her goal was the transformation of “our sense of values” so that we can “adequately help other human beings” (2.72). Her good works were in service firstly to the New Deal and generally to preservation of capitalism. Yet Harry Belafonte, famous singer, actor, and friend of ER, “believed that ER had become a ‘socialist’” (3.568). Many good people evolve politically, first becoming outraged by the crimes and injustices of capitalism, then embracing liberal reformism for a time, and ultimately arriving at revolutionary socialism. So it is easy to imagine a woman of ER’s depth, intelligence, and humanity abandoning liberalism and concluding that capitalism must be abolished. In 1933 she even proclaimed, “There is nothing so exciting as creating a new social order” (2.1). But Cook clarifies that ER was “a democratic socialist” (3.1) and, until her death in 1962, was “committed to a liberal vision” (3.569). ER herself, in response to reactionary capitalist attacks on the New Deal, called for liberalism to be celebrated: “The United States needs to resurrect with conviction and daring . . . the good American word liberal” (3.570).

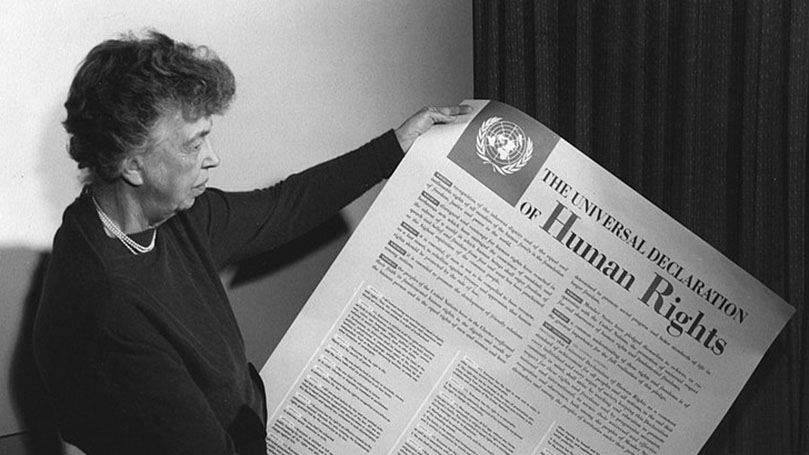

Her great heart led her to issues big and small: she protested war toys, toured the country addressing peace groups, challenged profit making in the arms industry (Cook, 2.494), and ended lectures with a “call for love as a principle in life . . . not as a doctrine but as a way of living” (2.494). She helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. ER could not abide “the fascist devastation of Spain” (2.383), “loved to hear the ‘Six Songs of the International Brigade’, and for many years kept on her desk a little bronze figure of a youthful Spanish militiaman in coveralls that was a symbol of the antifascist cause” (2.507). She “never accepted the abandonment of Spanish democracy” (2.507).

Her great heart led her to issues big and small: she protested war toys, toured the country addressing peace groups, challenged profit making in the arms industry (Cook, 2.494), and ended lectures with a “call for love as a principle in life . . . not as a doctrine but as a way of living” (2.494). She helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. ER could not abide “the fascist devastation of Spain” (2.383), “loved to hear the ‘Six Songs of the International Brigade’, and for many years kept on her desk a little bronze figure of a youthful Spanish militiaman in coveralls that was a symbol of the antifascist cause” (2.507). She “never accepted the abandonment of Spanish democracy” (2.507).

This activist First Lady encouraged college students to question authority: “Do not always believe your country is right” (Michaelis, 337), and “when in 1960 the sit-ins for integration began, ER urged college students everywhere to ‘go south for freedom’” (Cook, 3.564). She “thrilled to the possibilities of ‘a new people’s art’ with community theaters” for children and Black, Jewish, and Spanish audiences (2.268). ER asked, “Why should higher education not be free?” and “Why should girls not be included?” (3.513).

ER’s personal life outside the confines of marriage included romance, sexual intimacy, and friendship with men and women. Her lengthy romance with journalist Lorena Hickok is termed “the most ardent and absorbing relationship of her middle years” (Cook, 2.2).

She was a prolific writer, publishing “countless articles and six books” during 1933–38 (Cook, 2.7) and her newspaper column (My Day) six days per week between 1936 and 1961 (thereafter, three days a week until 1962). She worked long hours but once humbly shared, “If I feel depressed I go to work.” “Work had always been her antidote for depression,” writes Michaelis (493).

This reader found Michaelis to be rough going. It is a shame when a writer’s style overshadows even a beloved subject. But ER’s story is so compelling that my struggle to read Michaelis sent me back for a second reading of Blanche Wiesen Cook’s Eleanor Roosevelt. Through three volumes her straightforward style and crisp, clear, manner is never a barrier for an earnest reader who wants to know and feel close to ER.

What is the takeaway from ER’s story? As Cook concludes, “It is amazing how radical simple decency has been made to seem” (1.17). This wonderful woman’s caring and decency apparently posed such a dire threat to American capitalism that the FBI targeted her and amassed a vast, 3,000-page file or, as Cook calls it, “one of the wonders of modern history” (1.502, 1.3). And defenders of capitalism labeled her as “more dangerous than Moscow” (1.19).

It was said that ER “became the very symbol of New Deal energy and its philosophy,” and “her candor, her sincerity, her serenity have won even many of the bitterest critics of the New Deal” (Cook, 3.356). But the New Deal has been characterized as “an elaborate scheme for stabilizing capitalism” (Lipset and Marks, 210). The great historian Howard Zinn wrote:

When the New Deal was over, capitalism remained intact. The rich still controlled the nation’s wealth, as well as its laws, courts, police, newspapers, churches, colleges. Enough help had been given to enough people to make Roosevelt a hero to millions, but the same system that had brought depression and crisis — the system of waste, of inequality, of concern for profit over human need — remained. (394)

Like slavery, capitalism cannot be reformed. It must be abolished.

References

Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Gary Marks. 2000. It Didn’t Happen Here. New York: W.W. Norton.

Zinn, Howard. 1980. A People’s History of the United States. Harper Colophon.

Images: top, Wikipedia (CC BY 2.0); Eleanor at age 14, Wikipedia (public domain); ER with Mary McLeod Bethune, Wikipedia (public domain); ER speaking at the United Nations, Wikipedia (public domain).

Join Now

Join Now