As we round out Women’s History Month, we honor Nellie Allen Stone Johnson, radical farmer, African American union leader, NAACP and Urban League civil rights activist, Farm-Labor organizer, and Young Communist League member, who left an inexhaustible and distinguished legacy of struggle.

Born Nellie Allen in 1905 to a rural Minnesota family of radical farmers, educators, and activists, the soon-to-be movement leader learned the importance of organizing in community at an early age. She entered the world on a farm in Dakota County and lived there until she was eight years old, at which time she moved to a farm in Pine County. There she maintained childhood friendships with other Farm-Labor comrades from the Minnesota Communist Party district, like Clara Jorgenson and Jack Brown. In her autobiography Nellie Stone Johnson: The Life of an Activist, she emphasized the importance of her farming background and how it contributed to her intellectual curiosity and organizing initiatives. “The truth is, a lot of how I think of myself comes from the farm, a farm gal from Minnesota,” she wrote.

Stone Johnson’s father, William Allen, was a member of the Nonpartisan League and the Farmers Holiday Association, organizations founded by socialist farmers that created and maintained cooperative state-run mills, warehouses, grain elevators, and stockyards. The cooperative movement, proliferating at that time, encompassed a vast network under which farmers and others would organize and build a self-sustaining material world grounded in principles of economic and social justice.

Mr. Allen helped organize the Finlayson Power cooperative and the Twin Cities Milk Producers Association and encouraged Pine County farmers to join these dairy and electrical cooperatives. He also encouraged his daughter to organize in her youth. “I remember Dad had me pinned to the saddle at thirteen doing Nonpartisan League work,” the future labor and civil rights leader said. “I was doing the distribution of literature to the farmers. I kept that horse walking just so I could read!”

She was also influenced by her father’s involvement both in revolutionary politics and as a Black progressive elected official. Mr. Allen was elected to the Dakota County School Board and the Pine County School Board, the Clover Township Board, and to the District board of the Rural Electrification Administration in the first couple of decades of the 20th century. Stone Johnson articulated her father’s political platform as one that “supported good, equal opportunity in education, good training in jobs, and the family farm. There was nothing scary about it, except to the power structures of racism and money.”

Her mother and grandmother were also both influential to her political and ideological development. Both were trained as teachers, and her grandmother was also elected to the Pine County school board, leading Nellie Stone Johnson to advocate for equal opportunities in education throughout her life.

Some of the activist’s educational leadership positions were on the boards of the Minneapolis Technical College, the Minnesota Higher Education Board, and the Minnesota State Colleges and Universities Board of Trustees. She also helped establish a scholarship fund, which is awarded annually to help students of color from union families with post-secondary education. Additionally, in 1995, she received an honorary doctoral degree from St. Cloud State University.

Her leadership in education derived from decades of grassroots organizing, sometimes outside of the normalized structures. One example was a day in 1938, when the union organizer was attending a labor commission meeting. Stone Johnson insisted that the Minneapolis teacher’s union hire more teachers of color, specifically Black women teachers and Jewish women teachers.

Her leadership in education derived from decades of grassroots organizing, sometimes outside of the normalized structures. One example was a day in 1938, when the union organizer was attending a labor commission meeting. Stone Johnson insisted that the Minneapolis teacher’s union hire more teachers of color, specifically Black women teachers and Jewish women teachers.

According to labor meeting protocols, she should have written a resolution to be passed through her local, which would have then been presented at the central labor body, but due to her passion for advocating for equal opportunities in education, she bypassed procedures and brought the resolution directly to the central labor body, where it was passed. “I did something unorthodox on that resolution to support equal opportunity,” she later commented. “I just wanted equality in anything I went after — no brakes on going to school or the literary learning part of things, or what kind of work I could do, or that I could be trained for if I liked it.”

As a student, the activist attended her first two years of high school in Clover Township in Pine County, which accommodated students until the end of their sophomore year. When she was supposed to have entered her junior year of high school, she relocated to North Minneapolis to live with her aunt and uncle in order to earn her GED through the University of Minnesota extension program.

It was at the University of Minnesota where the young radical would frequently listen to Paul Robeson sing at Northrop Auditorium. It was during these years that Stone Johnson became close friends with socialist union organizer Swan Assarson, who encouraged her to join the university’s Young Communist League (YCL) and mentored her in organizing hotel and service industry workers.

In her autobiography, she reflected on the ways in which her time as a comrade in the YCL influenced her lifelong union organizing, work in education, and her political views:

“I was attracted to the Young Communists. They had the best programs on education and training for labor — they went way beyond anybody else. They talked sense …The Young Communists talked about the oppression of all people, and pushed hard to educate and organize to stop it.

“They got members by furthering education, why people should vote, why people should further certain political issues. They believed in doing good educational work, and didn’t just talk about it. And they believed whole-heartedly in better education for everybody.

“I was pretty active [in the YCL] for a couple of years or so. I just had a lot of other things to do, thought I would learn from them what I could, especially about organizing. I set about putting those efforts into the unions and the NAACP.”

It was around this same time that the young labor and civil rights leader was finishing her degree, organizing with the YCL, and living in North Minneapolis, that she also took a job in 1924 as an elevator operator at the all-white, all-male Minneapolis Athletic Club. While working there and at the West Hotel, Stone Johnson experienced racist workplace discrimination and anti-union retaliation, and described sexual harassment of women workers as rampant. “They knew which girls to put their hands on … They felt they could do anything to a woman. The Athletic Club was often a den of animalism. Women didn’t count.”

She knew that organizing and collective bargaining could improve all workers’ conditions, especially those most exploited, like working-class women of color. While at the Minneapolis Athletic Club, the bosses cut workers’ wages from $15.00 to $12.50 per week. The young Communist responded by organizing the workers into a union. The bosses retaliated. “What got me fired from the Athletic Club the first time, in the late twenties, was labor activities — everybody knew that.”

She knew that organizing and collective bargaining could improve all workers’ conditions, especially those most exploited, like working-class women of color. While at the Minneapolis Athletic Club, the bosses cut workers’ wages from $15.00 to $12.50 per week. The young Communist responded by organizing the workers into a union. The bosses retaliated. “What got me fired from the Athletic Club the first time, in the late twenties, was labor activities — everybody knew that.”

It was through her initial phases of organizing with the YCL and organizing workers at the Minneapolis Athletic Club that Stone Johnson began to work with the Hotel and Restaurant Employees (HRE) Union, and later developed into one of the principal organizers of Local 665. She would come to act as a local joint executive board member of the HRE, was elected the first woman vice president and contract negotiator of the Minneapolis Hotel and Restaurant Workers Union, and also was elected to be the first woman vice-president of the Minnesota Culinary Council.

At the time of her initial union organizing at the Athletic Club, she was living with her aunt and uncle in North Minneapolis. Her uncles were rank-and-file union members in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and very dedicated to trade unionism, as was the owner of the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder at the time, Cecil Newman. The Minnesota Spokesman Recorder is the “the oldest Black-owned newspaper in the state of Minnesota and one of the longest-standing, family-owned newspapers in the country.” Stone Johnson would frequently reference articles published in the Recorder, while organizing workers in the dressing room before and after shifts.

The labor leader was also influenced by Black and Jewish organizers at the time, including Frank Boyd from the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in St. Paul, and Mr. Newman, Rubin Latz, and Mike Finklestein from the Ladies Garment Union. At the time, it was rare to see a woman in labor leadership, particularly an African American woman. “Most of us women leaders kind of slipped in the back door. Often it seemed like I was the only woman.”

Nonetheless, she persisted and began to assist college campuses in setting up labor centers throughout the country. She helped to establish the labor centers at Columbia University in New York, the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and the University of Minnesota. “We had a lot of things [at the labor center] at the University of Minnesota, some through the Young Communist League,” she noted.

This is also the time period when she met and became close with Hubert Humphrey, who would later become mayor of Minneapolis, a U.S. Senator, and U.S. Vice President. In 1938, Swan Assarson introduced his Comrade to Hubert, who was finishing up his graduate work on a Works Progress Administration project.

Stone Johnson described her original encounter with Hubert in 1938: “It happened on campus. I had been to a meeting of the Young Communists. I ran into Swan, and boom, he introduced me to Herbert … There were two basic things that Herbert and I fought for and were hard-nosed about that changed this country: the right of labor to organize, and the right of black people to live free.”

The civil rights and labor leader became a close personal friend and advisor to Hubert Humphrey, although he later engaged in anti-communist tactics, such as purging Communists from the DFL when the two parties consolidated. Although the influential activist had a large impact in Humphrey’s political life, she was clear that they did not always concur with one another ideologically. “We wouldn’t necessarily agree on everything, especially the Young Communist League. They were very strong in labor education as well as in the area of separation of church and state, and [on the need] to keep religion and private schools from encroaching on the public schools. They talked about equality of education when most people wouldn’t.”

Stone Johnson was focused on building strategic alliances with others to achieve concrete improvements for workers and oppressed peoples, even when she did not always align politically with them. This was apparent in her relationship with Hubert Humphrey, and she often noted how her background and views differed from his and other mainstream politicians with whom she worked closely in coalition:

“We [Hubert and I] saw ourselves in different ways: he was this academic from Macalester College, this intellectual from the U of M, and I was this radical farmer. I was an activist; you read those cliches that get attached to other people — the reds — and you knew you fit into that, too, but you didn’t care because you believed in the good things you were working for.

“Some of the arguments we’d have about Communists: I had to tell him, some of those people he was talking about was me! I was not at all ashamed to be called red … Basically, ninety-nine percent of us were workers, and if we made it better for workers and the farm coalition, we’d make it better for everyone. I was coming out of the Farmer-Labor Association and the Nonpartisan League, getting rid of racial and gender discrimination, and we believed in a lot of collectivism, and maybe Hubert felt that went too far.”

In 1943, while Stone Johnson was still very active in the labor movement, including working with progressive trade unionists at the Minneapolis Central Labor Union, she also became a member of the committee that merged the Farmer Labor Party with the Democratic Party, creating the Minnesota DFL. One year later, Swan Assarson encouraged her to run for Library Board of Minneapolis on the newly established party ticket. She became the first African American representative to hold elected office in the city.

During her six year term on the Library Board, she pushed for legislation in fair employment practices, both at the city and state levels. “The day after the election I went to the board, I had a meeting, and I wanted to know why the administration didn’t have any black people working at the library. As for the library folks, I just went and talked with the personnel department, and before I knew it, we had black people working there!”

In addition to advocating for fair employment practices during her time as an elected official with the Library Board, she was also a key figure in helping to draft Minneapolis’ nation-leading fair employment ordinance and its fair housing ordinance. After working diligently to get this legislation passed in Minneapolis at the city level in 1947, she continued to work for the passage of similar laws on the state level in 1955 and 1960.

While working with the Library Board, Stone Johnson also supported and campaigned for Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry Wallace. She was still working closely with communists at the time.

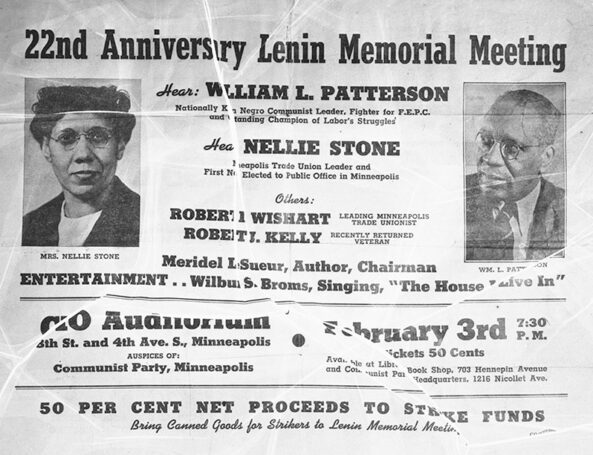

In February 1946, she was the keynote speaker, along with William L. Patterson, national leader of the Communist Party USA and International Labor Defense, at the 22nd Anniversary Lenin Memorial Meeting in Minneapolis. Comrade Meridel Le Sueur chaired the meeting, where nonperishable food supplies and monetary donations were raised for striking workers.

In February 1946, she was the keynote speaker, along with William L. Patterson, national leader of the Communist Party USA and International Labor Defense, at the 22nd Anniversary Lenin Memorial Meeting in Minneapolis. Comrade Meridel Le Sueur chaired the meeting, where nonperishable food supplies and monetary donations were raised for striking workers.

After her term on the library board ended, red-baiting became rampant in the DFL around the late 1940s and early 1950s. “I knew that after the DFL merger some Democrats would try to throw us on the dung heap because we were radicals. I’ve always said you have to be radical to change things in this country. That’s been called socialism, or even communism,” she said.

The red-baiting that she faced from forces both on the right and the “centrist” left was significant. For example, at the 1948 DFL convention, Orville Freeman was leading the charge to refuse to seat her as a delegate.

Freeman, a staunch member of the anti-communist sect within the DFL party, spearheaded an intra-party campaign to purge the newly formed DFL party of any members with communist affiliations. (Orville Freeman’s son, Mike Freeman, was recently the subject of mass protests in Minneapolis in 2020, after he repeatedly supported MPD killer cops during his tenure as Hennepin County Attorney for almost a quarter of a century).

Stone Johnson explained that “red-baiting created divisions between Black and Jewish people. The enemy of both wanted to put something in the mind of the other. Part of what the conservatives, the establishment, was saying was how they wanted to split the labor coalition.”

In the early 1950s, the powerful civil rights and labor leader was interrogated by the FBI and ordered to appear before a federal grand jury for the crime of “advocating radical education.” Like many others at the time, she was forced to attend the federal grand jury trial alone, without Doug Hall, her civil rights attorney and labor lawyer. She was also refused any access to outside counsel.

Knowing that she would be questioned about her membership in the YCL and her party associations, Stone Johnson explained that the night before the grand jury trial she didn’t sleep, ruminating about what simple thing she could respond with at the trial so as to not incriminate her comrades and fellow labor activists.

When the federal grand jury prosecutor, Howard Gelb, grilled her about who was a member of the YCL or any communist organization (CPUSA), she replied with a question: “Are you asking me whose membership card I have ever seen?”

When Gelb confirmed that was indeed his question, her reply was, “I can truthfully tell you, I’ve seen nobody’s but mine.”

Shortly after the grand jury trial, she was pressured to publish a letter in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune and Spokesman Recorder confirming her break with the YCL and any “leftist” parties. “I wanted to get everybody off my back was basically it,” she explained. “The red issue did seep in, but that wasn’t quite what bothered me — I was raised that radicalism would be red-baited.”

Six months after the letter was published, Stone Johnson became one of six Minneapolitans honored by the city’s Chamber of Commerce for distinguished public service.

Although the labor leader recognized the award was for her work in equal opportunity in education that she had advocated for during her time at the library board, she also recognized that the gains made were collective efforts, not borne from a single individual.

“I thought that award was not quite fair to the other people, from other organizations, who had done right promoting those issues too. But the fact is, that was my philosophy, not any crazy label they tried to stick me with.”

Even though “the red-hunters in Washington”, as Stone Johnson referred to the FBI, put her through an excruciating and traumatic federal grand jury trial, and even though civil rights leaders at that time — particularly those affiliated with newly-formed DFL party — were under immense amount of pressure to dissociate themselves from Communist or socialist parties, she maintained her steadfastness and commitment to her principles.

Many comrades locally in our club and district recall how she would warmly greet and actively associate with many of our party leaders throughout several decades in the post-McCarthy period.

“My association and philosophical belief with those parties, the belief within me, was true, but my bottom line was always about jobs and education.”

Throughout the following decades, she not only continued to work within the labor movement, but was also a leader in organizations throughout the city for people of color. For twenty-six years, she was on the executive committee of the Minneapolis NAACP and served on its national committee. She also chaired committees for the Urban League and recruited and ran the campaign for Van Freeman White, who was then elected as the first Black Minneapolis City Council member.

Although Stone Johnson was offered many political jobs, she chose to operate her own sewing repair shop so that she was not beholden to any boss’ opinions about her politics and union activities. “I didn’t mind having constituents, but to do a paid job puts you at the mercy of a lot of politicians.” Instead, she established Nellie’s Shirt and Zipper Repair in 1963, never working less than twelve hours a day and often completing 16-hour shifts. She insisted in 2001 that even at the age of 95, she still dreamt about sewing.

Nellie Stone Johnson was not only a founder of the DFL; she was also a member of its Executive Committee, Agricultural Committee, and Black Affairs Department. In both 1980 and 1984, she was elected to the Democratic National Committee. The movement leader was also a close friend and mentor to Senator and Vice President Walter Mondale and joined a delegation to Africa with Vice President Walter Mondale in the 1980s.

In an interview conducted by students later in her life, Stone Johnson expressed her surprised to have received security clearance to travel with the African delegation due to her previous organizing with the Young Communist League and her pursuit of socialist goals.

“I never could figure out, as radical as I was as a young person, how in the world they would clear me to make a state department trip,” she said. “But they did. In fact, I asked VP Mondale, ‘How did you clear me to make a state department trip?’ He responded with, ‘Your work in ordinary politics, in employment, and in education seemed to have done the trick!’ ”

A year before she passed away in 2002, at the age of 96, Stone Johnson described her concerns with the mainstream DFL establishment. “There are simply too many pockets of conservatism in the DFL, too many MBAs who determine how things go, from the point of view of the business faction. They’re making rules to give more power to the private sector than the public sector. I can tell you, the private sector is the root of racism, the determining factor on whether people are discriminated against.”

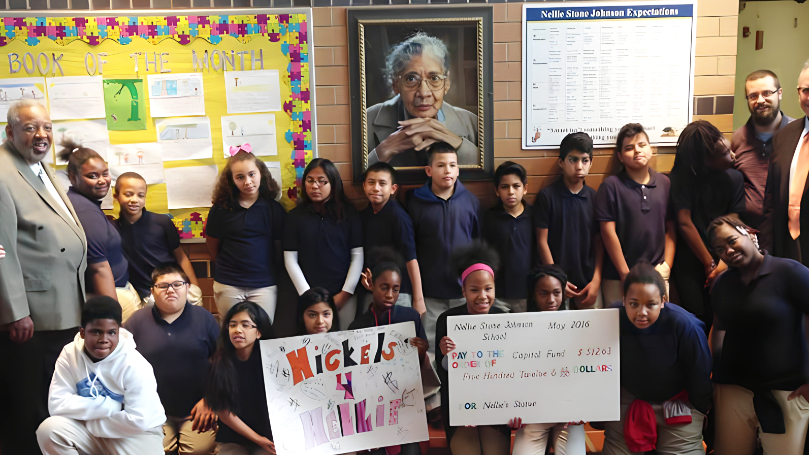

Nellie Stone Johnson was a woman of many “firsts.” She was the first African American elected official in Minneapolis, the first woman vice president of her union, the first woman contract negotiator in her union, the first woman vice president of the Culinary Council, and many other distinctions. In November 2022, Stone Johnson posthumously achieved two more distinctions: she became the first woman and Black Minnesotan to be memorialized in a statue at the state capitol, and is also believed to be the first Black woman memorialized in any state capitol building in the entire country.

Even though she received a plethora of accolades for her incredible lifelong work, Stone Johnson remained determined that what she most wanted to be remembered for was her legacy of fighting for the working class — “to be remembered for working for the family farmer and labor — the salt of the earth. Those are the ordinary people in the state of Minnesota!” she insisted.

This biography is based on interviews conducted with comrades from the Minnesota/Dakotas District, as well as biographical information and quotes from the following sources:

OH 30.37 Nellie Stone Johnson. Interview by CPUSA MN District Leader Carl Ross, 1981. Oral History interviews of the 20th Century Radicalism in Minnesota, Oral History Project. Minnesota Historical Society. 2 hours, 33 minutes. 16 pages.

Weihe, Jeffery (Director). (2000, June 4). Nellie Stone Johnson (Season 6, Episode 1) [TV series episode]. In D.P Begin (Executive Producer), Don’t Believe The Hype. TPT; Twin Cities PBS Productions.

Johnson, Nellie Stone. Nellie Stone Johnson: The Life of An Activist; as Told to David Brauer. St. Paul: Ruminator Books, 2001.

Images: Students move Nellie Stone Johnson statue closer to reality by Workday Magazine; Nellie Stone Johnson in 1943, courtesty of Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota; Nellie Stone Johnson statue at MN state capitol, 2023, by Rebecca Pera, St. Paul, Minnesota; Nellie Stone Johnson with Count Basie Orchestra at the Riverview Theater, 1980, Minneapolis, Minnesota, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota; Nellie Stone, 1943, and Minneapolis Library Board, 1945, courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Lenin Memorial Meeting Notice, 1946, Minneapolis, Minnesota, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota; Nellie Stone Johnson with other NAACP leaders, NAACP Office, 1954, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Nellie Stone Johnson at Nellie’s Shirt and Zipper Repair, 1963, Minneapolis, Minnesota, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota;

Join Now

Join Now